Of Lori McKenna's debut album, Paper Wings & Halo, an AllMusic.com critic so many years ago — that would be me — wrote, “From McKenna's pen flow timeless, heart-grabbing melodic lines and psyche-splintering stanzas. … If this album is any kind of signpost, look for McKenna's light to be shining bright for a long while to come.” All these many years later, her light is, indeed, shining bright — on the Billboard country charts, at the Grammy Awards, and, now, on her 10th solo record, The Bird & the Rifle. Produced by Americana master Dave Cobb, the new collection is utterly captivating, filled with everything we've come to expect from McKenna — glimpses of real life and real love laid bare in profound and poetic, stark and stunning detail.

Because I go all the way back to Paper Wings & Halo with you …

WOW!

Yeah. So I've been thrilled to watch your ascent over the years. How are you processing it all? Does it ever really sink in — everything that's happened in the past 15 years?

I don't ever really get to a point where it doesn't amaze me how lucky I am in this career. As soon as I start getting complacent with “Am I doing enough?” something appears. I don't know why I'm as lucky as I am, other than the fact that, as I would say to my kids, it's because I keep trying. The thing about music is, there's always more to learn. There's always a better song to write. You always hear a better song that you wish you wrote. And it's changing all the time. So I go to bed a lot and think, “Shit, I'm lucky!” [Laughs]

[Laughs] Do you feel like songwriting and other talents like that are inherent gifts that we can't really take credit for? I mean, sure, you can work to perfect the craft around it, but without those seeds …

I do think there's a weird thing that happens sometimes where … like “Humble and Kind,” for example: The chorus, when I looked back on it, I thought, “Man, I really lucked out.” [Laughs] It's better than I think I knew how to do it, to be honest. Also, the hook on “The Bird & the Rifle” … I was in the shower the night before we wrote it, thinking, “What if you just said, 'Spreading her wings always brings the rifle out in him'? Maybe it doesn't land on 'the bird and the rifle.' Maybe that's not the hook.” That was just pure luck and thinking about something long enough. I don't want to be weird and say “the songwriting gods and all that come down.” And who am I to have any gods pay attention to me? I don't know. Sometimes, you do look back and say, “That turned out better than I think I know how to have made it.”

So there's some something going on that is bigger than you?

I think so. And I don't know, really, if there's a name for it. Other days, you can try everything and it's like, “Nope. Not happening.” [Laughs]

[Laughs] “Do not pass go.”

Yeah. “Today's not your day.”

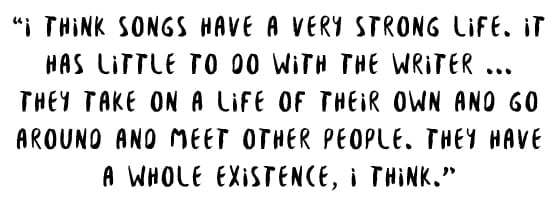

At the listening party for this new record, you said something about how you go around checking for melodies in your guitars. That would kind of indicate that you feel like songs are already out there just waiting to be caught … maybe?

I like to stew on little ideas. Those are usually the best ones. If I think about it for a couple of days, then I get to sit down and write it, that's usually when it's formed correctly. But sometimes, you don't know they are there at all. It's funny. I don't know what it is. I think I've purposely tried to not over-think it because you can mess yourself up. There's definitely something going on that isn't concrete, in the process. That's why I always think that songwriting classes, they must be so hard. But, really, if you just keep trying … That sounds like a bad thing to say to somebody who's tried a lot and hasn't gotten where they want, but it's really the only way to do it — just show up.

Right. Over these many years, what has changed for you, in how you approach the job or how you approach songwriting?

It's funny because, originally, I was doing open mics, then I started doing shows, then I put out a couple records … that was all where my world was, “My wife does this thing. She does these shows and it's cool” … [Laughs]

[Laughs] “Humor her. It's fine.”

[Laughs] Yeah, “It's fine. She pays for the groceries, sometimes.” But I think my husband knew that I had to do it. Young moms always say, “Make sure you take care of yourself. Have something for you.” It was always my thing for me. It was like that. It was my hobby for a while. And I made a lot of money at the hobby, now and then. When the Faith [Hill] thing happened, it wasn't like a door opened; it was like a universe opened, because I had never co-written before. I didn't know, really, what a publishing deal was.

You were just this little folkie out of Boston.

Yeah. I kind of wanted to learn about all those things. I knew certain people who had some sort of access to it, but I didn't really know or even know how to figure it out, to be honest. Since then, it's just been one surprising turn after another.

I remember when I got my deal with Warner Bros. We went out to eat at the 99 with the kids. I was like, “Babe, I think I got offered a record deal.” He was like, “What? No way.” [Laughs] We're at a 99 and I'm like, “Should I do this? I feel like I should.” It's always surprised me, in this crazy way. Now, the biggest change is that it's a full-on part of all our lives. My husband knows the business now, to a … I don't know that much, myself, but we know a little bit about it together. Like changing publishers and stuff like that, I can talk to him about it. We're all on the same page as far as “This is what mom does.”

“It's not just her hobby anymore. It's putting you through college.”

That publishing deal opened up the whole thing of writing songs for other people, which was a whole world that I hadn't really explored before. I love that part of it.

There's that part of it and there are your songs. And, then, some songs do double duty — like “Humble and Kind,” which Tim McGraw took to number one, and “Three Kids No Husband,” which is on Brandy Clark's new record. You also said at the party that, if you had a voice like Carrie Underwood's, you would write differently.

That didn't sound bad did it? I was thinking about that after … I love her voice.

No, no, not at all. I'm just curious … would it be bigger melodies? I mean, you would still be you , so you would have the same message.

Yeah. I think my melodies would be bigger. I really think our limitations form our style. I play the guitar the way I play because I can't play the guitar like a great guitar player. But that guitar part might sound like me. And it's my limitations that took me there more than my craft. I think the same is true in writing a song by yourself or writing a song where, that day as a co-writer, you're singing for the day. I write with Hillary Lindsey a lot and she can sing anything and she is really great at melodies. Then, you're co-writing with somebody who can find those big, beautiful melodies that I won't by myself.

I also think, because I like simple songs and my voice lends itself to a simple melody, then the words can't be general words. The words have to be the thing that carries a song. So, I think if I could sing anything, my songs wouldn't be as lyrically driven as they are. Does that make sense?

Totally. I look back to a song like “Don't Tell Her” — which still slays me — and everything that makes you a great songwriter is in there: the attention to detail, the search for intimacy, the spin on the dynamics. In a weird way, that tune is almost like a foreshadowing of or bookend for “Girl Crush.”

OH! That's true, isn't it? I never thought of that … because I always forget about that song. [Laughs] But, when you say it like that, it is a little bit the same story. It's hard to not think of that scenario, when you've been married a long time or in a relationship a long time, because you know the person so well and they know things about you that nobody else does. And you know, if they're going to go somewhere else, this stuff could come up in conversation. [Laughs]

[Laughs] Your secrets aren't safe.

Or even just things that person knows and nobody else knows them. It's not good or bad; it's just a thing. So I think anyone in a long relationship would have that thought process. But that's interesting.

I also think your two woman songs — “All a Woman Wants” and “If Whiskey Were a Woman” — I see those as a pair.

Oh, really?

But here's the thing: Guidebooks? Disclaimers? Statements of fact? How do you see those songs versus how they are received?

“All a Woman Wants,” I think came from a conversation with Gene, my husband, about, “Damn. I'm really kind of easy, here.” [Laughs]

[Laughs] As far as women go …

Yeah. I was talking to a songwriter friend the other night who was like, “I'm getting married and everything's so cool. Am I going to still be able to write? Everything's good right now.” You know, that little bit of fear. I said, “No. All you have to do is take that thought and blow it up, just exaggerate the shit out of it for a little while, for three-and-a-half-minutes, and you'll have a song.” [Laughs]

That's really what it was. I remember kidding around with him, like, “Dude. I am easy. I have like three things!” When you start picking it apart, most women just really want to feel like they are your everything. I got in trouble for that song, though. A couple of people were like, “How do you know what I want?”

“I do want the diamonds!” [Laughs] “Drip me, baby!”

[Laughs] Yes! But the fact that he wants you to have them … My neighbor came up and said, “I love that line!” Gene didn't understand it. I had to explain it to him! [Laughs] I did! He was like, “What's that diamond thing?” I was like, “Listen to it! I think it's kind of clear. Come on, pay attention!”

“If Whiskey Were a Woman” is that same thing, I guess, in the way that he wants something. It's like, “Oh, I can't do that.”

[Laughs] “So go have a drink, buster.”

[Laughs] Yeah, yeah. “You won't let me do that, so …” That's so interesting, the way you think of it. I love it!

What would the perfect career look like for you? Do you have it?

I think so, yeah. People ask me sometimes, as far as the two separate categories of songs, “How do you do that?” I guess they want to know, logistically, if I think of it this way or if I write about myself, usually it's in this category. Sometimes not. But it hasn't bothered me that there are those two things. I've really enjoyed having those two things.

For a while, I started picking it apart and thinking … I don't like leaving home, to be honest. I like songwriting best. That's my favorite part. I like singing. I like playing. I like standing in front of people. But I don't love all that, as much as I just want to be able to write a great song. I want people to hear them. But I have this thing where I don't necessarily have to sing them — other people, every now and then, will sing them. And that still makes me feel great, so maybe I should just write for other people. I kind of did that, during Numbered Doors — I had that mentality of “I'm not going to travel for shows. I'm going to travel for writing because that's my favorite part.” It didn't work. It wasn't going to crash land … yet. But it would've, eventually.

Then my publishing deal came up and I started talking to Beth Laird [of Creative Nation]. Every other publisher, when I was like, “What about my artist side?” They were like, “You can do whatever you want.” But Beth was like, “Hey, what about your artist side? I think that's an important piece. I think that makes you a better writer.” So I needed that little selfish part to be like I want to write the best song for my little project. I don't know what it does to me, but it's really important to me. And I didn't know that. I was maybe starting to think it or maybe starting to lose it. It was going to go one way or the other. Then Beth came in and sparked that, again, in me. And my friends probably would have, eventually … like Barry Dean is really perceptive about what I need, as a creator, and what is helpful. Other people cutting my songs was something I never thought was possible. The fact that I get to do both is amazing.

Dreams do come true.

Even if you hadn't dreamed them! [Laughs] I wouldn't have thought, “Oh, I want this!” That was another thing Beth said to me, when I first started talking about signing with them. She's a goal person – like, “Write down these goals.” I've heard that a bunch of times, but I could never say out loud certain things … like, “I want to be a songwriter.” That sounds crazy! She taught me, and I remember talking to her one day and I was like, “Well, I want a Grammy.” How cocky is that?! [Laughs] I said that out loud!

[Laughs] And … SHA-ZAM!

When that all happened, I was like, “Beth! What did you do?!?!” [Laughs]

[Laughs] What kind of voodoo is going on down there?

Everybody write your goals down! It's incredible! [Laughs]

Photo credit: Becky Fluke