In early November, the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix, Arizona unveiled a brand new exhibition, Acoustic America, which celebrates iconic instruments of many heroes of folk, blues, bluegrass, and more. The exhibit is presented in partnership with our Dawg in December Artist of the Month, David Grisman and his record label Acoustic Disc, and showcases a remarkable collection of instruments that the museum states, “Have redefined music not only in the United States, but around the world.” This includes more than thirty instruments on loan from the Dawg himself.

“MIM is honored for this opportunity to collaborate with David Grisman and feature so many prized instruments from his collection,” says MIM senior curator Rich Walter, via email. “And after many years of loving his music, it has been a joy on a personal level for me, too. His influence as a mandolinist, composer, and bandleader is huge, and he absolutely changed the course of acoustic music as we know it today.”

Guests of the museum will be able to view storied and legendary instruments formerly owned and played by such luminaries as Earl Scruggs, Elizabeth Cotten, Mississippi John Hurt, John Hartford, Lloyd Loar, and many more. “Beyond the legacies of the individual artists and the beauty of these historic instruments,” Walter continues, “Seeing this collection together in one space is really striking because it reflects a broader American narrative. Exceptional individuals from diverse backgrounds crossed paths and connected their talents in ways that gave us distinctive new traditions that continue to inspire people around the world.”

To celebrate the new exhibition and Dawg in December, we’ve partnered with MIM to bring you these photos of select instruments from Acoustic America. Make plans to visit the Musical Instrument Museum in Arizona now! Tickets are available at MIM.org.

(Editor’s Note: Instrument information provided from the Acoustic America catalog.)

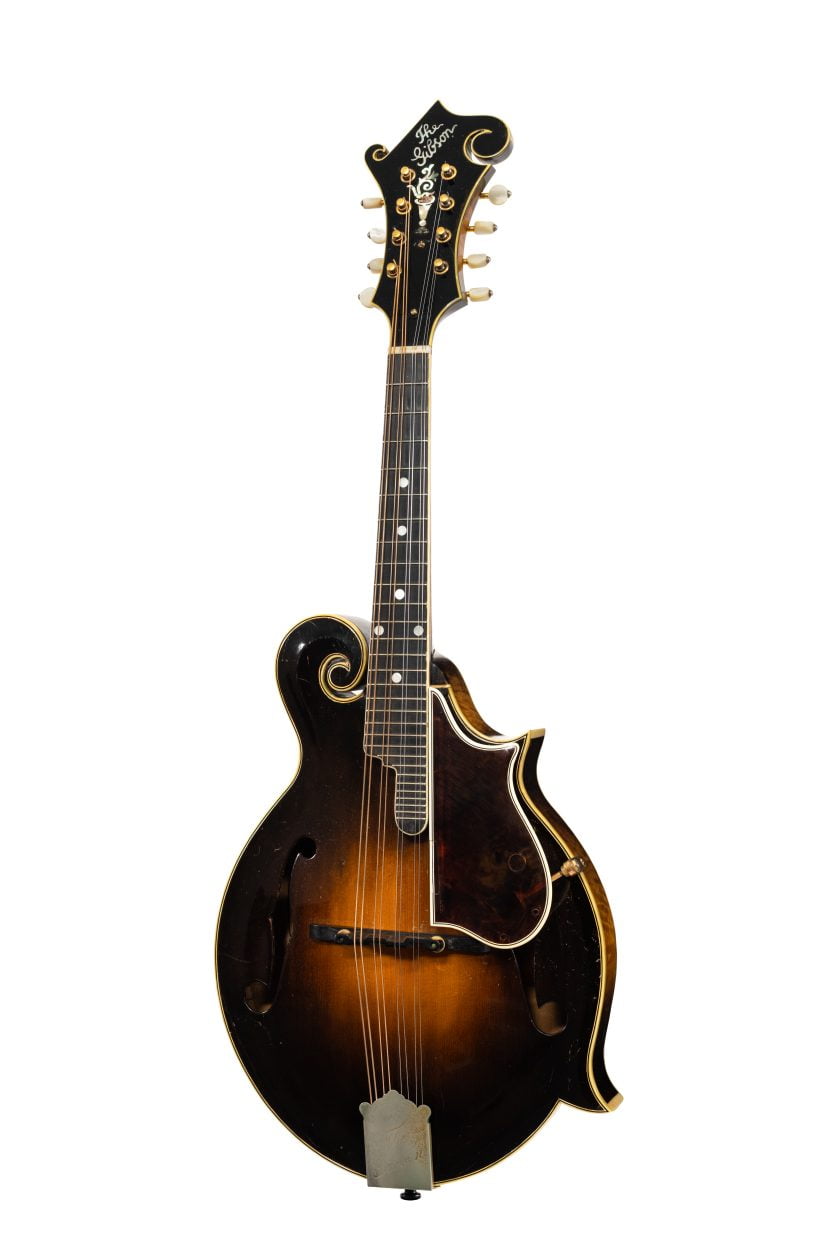

The F-4 model was Gibson’s premier mandolin until late 1922, when the F-5 was introduced. In addition to the characteristic oval sound hole and carved scroll, this early example features a three-point body style (note the points protruding from the body), elaborate torch and wire peghead inlay pattern, and special Handel tuning buttons with colorful inlays. David Grisman featured this mandolin on the cover of his first solo album, The David Grisman Rounder Album, and has recorded with it on other projects, including Tone Poems with Tony Rice and Not for Kids Only with Jerry Garcia.

Manager, talented musician, and legendary folklorist Ralph Rinzler (1934–1994) was one of David Grisman’s earliest and most influential mentors. Sharing a hometown of Passaic, New Jersey, Rinzler introduced Grisman to important recordings of folk music and inspired him to play the mandolin. Rinzler played this F-5 mandolin with the Greenbriar Boys, who were the first non-Southern bluegrass band to win at the Union Grove Old Time Fiddler’s Convention in North Carolina. He also managed the careers of Doc Watson and Bill Monroe and was instrumental in creating the first dedicated bluegrass festival in Fincastle, Virginia, in 1965. Two years later, Rinzler founded the Smithsonian Folklife Festival to celebrate and support living cultural heritage from around the world.

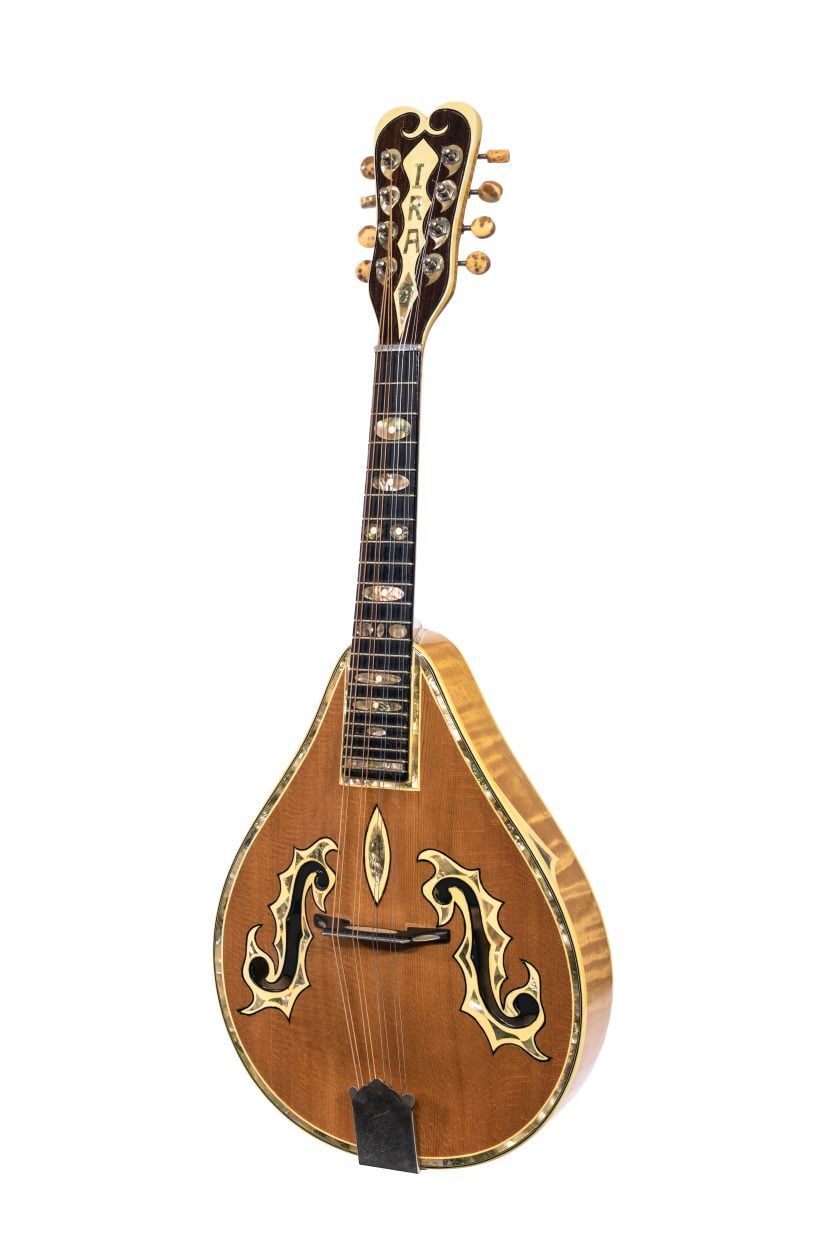

Few brother duet acts in country music were as influential as the Louvin Brothers. Ira and Charlie Louvin were born in Alabama in the 1920s, and their high harmony singing and Ira’s tasteful mandolin playing helped them define a sound popularized through radio broadcasts, commercial recordings, and appearances on the Grand Ole Opry – where they debuted in 1955. Ira customized this one-of-a-kind mandolin in the flashy style of professional country artists and played it extensively, including on the Grand Ole Opry stage. This special piece of mandolin history was also owned by David Grisman for many years.

This mandolin — serial number 75315; label dated February 18, 1924 — was the personal instrument of famed Gibson acoustic engineer Lloyd Loar. Loar was impressively inventive and patented designs for keyboard actions and electric instruments, among many others, but the F-5 Master Model mandolin is arguably his most iconic and enduring success. The interior of this mandolin is fitted with an original Virzi Tone Producer. F-5 mandolins with Loar’s signature on the label are the most valuable and sought-after in the world, and Loar F-5s from the batch signed on this date are known to be among the best-sounding. Perhaps it is not surprising that Loar kept this remarkable mandolin for himself!

This guitar was played extensively by the New Lost City Ramblers, who were pivotal to the national revival of Southern folk music in the 1950s and 1960s. Founding members John Cohen, Tom Paley, and Mike Seeger were dedicated to authentically reproducing folk traditions for new audiences. The group recorded several albums for Smithsonian Folkways and helped discover, document, and showcase talented artists such as Elizabeth Cotten, Dock Boggs, and Snuffy Jenkins. Prewar pearl-trimmed Martin guitars are among the most desirable acoustic instruments in the world.

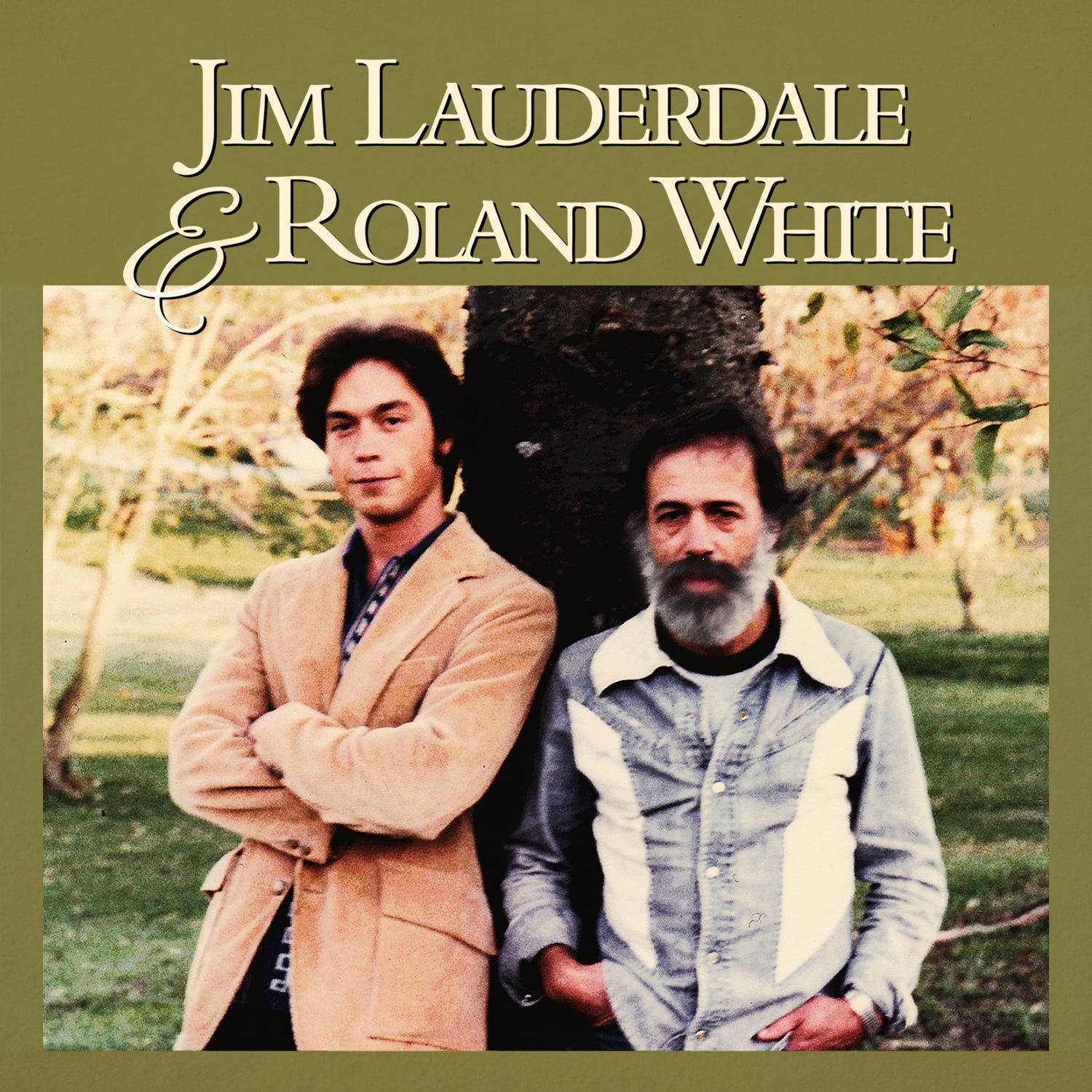

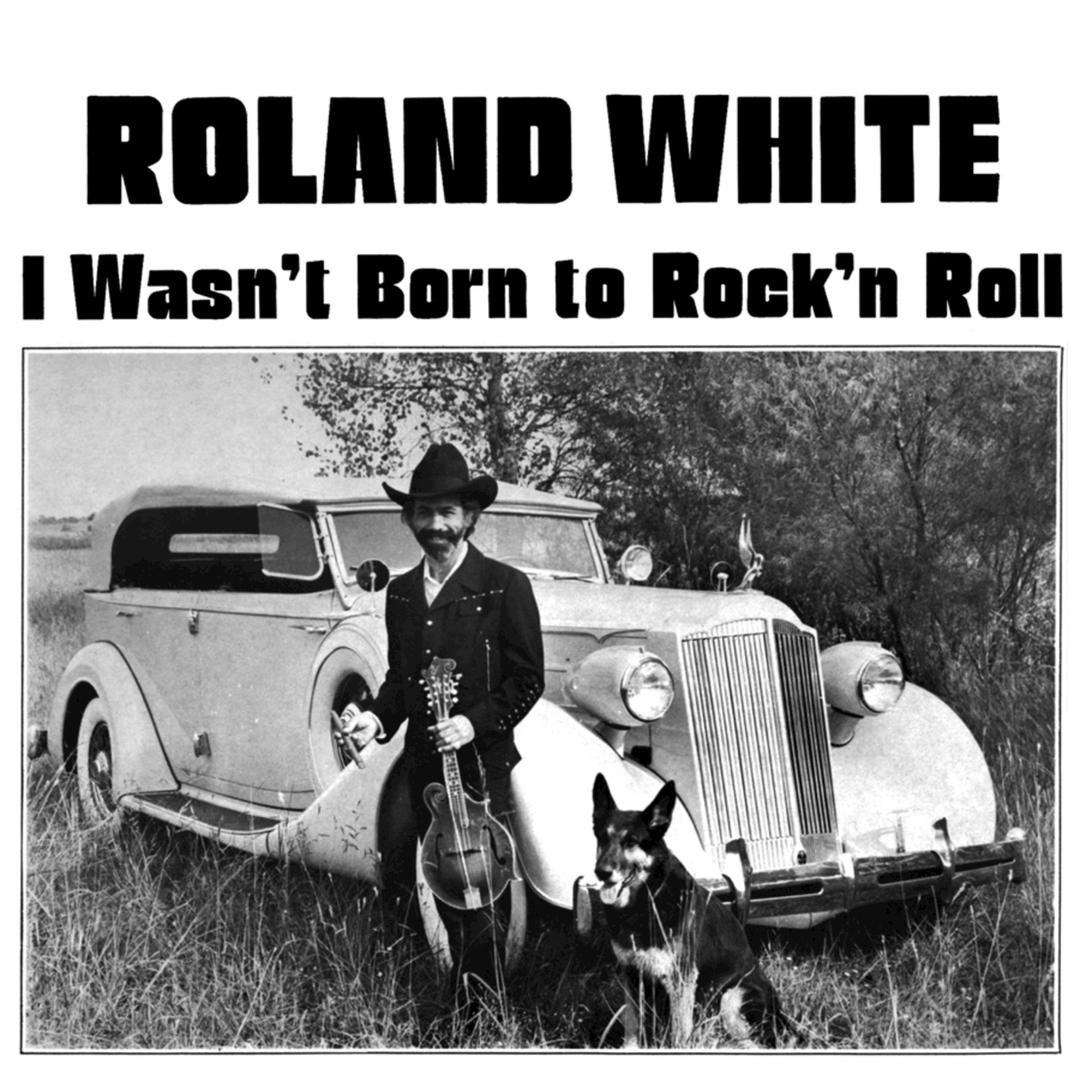

In 1961, the Kentucky Colonels, led by brothers Clarence and Roland White, performed on The Andy Griffith Show, under the alias “the Country Boys.” The Kentucky Colonels were one of the most exciting and influential bluegrass bands of their era, and their national television appearance would have been much of the United States’ first memorable exposure to bluegrass. Dobro player LeRoy McNees (AKA LeRoy Mack) played this Model 125 resophonic guitar during the show and for many years afterward. After the guitar was damaged at an airport, McNees restored and outfitted it with gold-plated metal hardware.

A young Alison Brown spent her entire savings on this then-new banjo built by Geoff Stelling, hoping to emulate the crisp, solid tone of Alan Munde, an influential older banjoist who played a similar Staghorn model. Brown played this banjo on her first album, 1981’s Pre-Sequel, and she later played it with Alison Krauss’s successful band Union Station. One of the most gifted banjoists in the world, Brown was the first woman voted Banjo Player of the Year by the International Bluegrass Music Association (in 1991). She has also won multiple Grammy awards, founded her own record label, Compass Records, and was inducted into the Banjo Hall of Fame in 2019.

Guitarist and composer Michael Hedges (1953–1997) used a range of innovative and unconventional playing techniques — such as alternate tunings and percussive tapping on the strings and soundboard — to expand the possibilities of what a solo artist could do. In rediscovering the sound of vintage harp guitars with dedicated sub-bass strings, Hedges reimagined the guitar as a full-spectrum compositional tool. His 1984 album Aerial Boundaries illustrated his astonishing talent and helped define the contemporary new age acoustic music of Windham Hill Records. Hedges nicknamed this favored harp guitar “Darth Vader,” and his use of harp guitars revived interest in these long-obscure instruments.

All photos courtesy of the Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix, Arizona.