Who invented rock ‘n’ roll?

Don’t answer that: It’s a trick question. Rock ‘n’ roll, like most complex sounds and genres and world-conquering forces, wasn’t actually invented. Instead, it germinated and mutated and mushroomed and erupted. It’s not the product of Elvis Presley or Sam Phillips, nor of Jackie Brenston or Louis Jordan. Rather, it is the product of all those people and more — all conduits for larger cultural ideas and desires. Rock wasn’t an invention, not like television or the telephone or the automobile or the atomic bomb. Similarly, its sub-genres and sub-sub-genres in the late 1960s weren’t inventions, more like waves swelling and cresting through pop culture.

The Beau Brummels didn’t invent country-rock in the 1960s, although they did help bring it into being. Long before the San Francisco rock explosion in the late ’60s shot the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane to national prominence, they were gigging around the Bay Area as one of the first American bands to respond to the British Invasion. In 1965, they recorded their breakout hit, “Laugh Laugh,” with a kid named Sly Stewart, later known as Sly Stone. They held their own against Southern California groups like the Byrds, the Standells, and the Electric Prunes (who were marrying their garage rock to liturgical music in one of the most esoteric experiments of the era). While tiny Autumn Records could never fully capitalize on their success, the Beau Brummels did achieve enough notoriety to appear in films and television shows. (The quality of those outlets, however, remains questionable: Village of the Giants, a kiddie flick starring Beau Bridges and Ron Howard, was skewered on Mystery Science Theater 3000.)

They have a full slate of excellent hits, each marked by songwriter/guitarist Ron Elliott’s melancholic lyrics and Sal Valentino’s unusual vibrato, which had a way of turning consonants into vowels and vice versa. The line-up shrunk from a sextet to a trio, which meant fewer harmonies, but a more streamlined sound. Released in 1967, Triangle strips away the electric guitars and, in their place, inserts folky acoustics and chamber-pop flourishes. It’s a song cycle about dreams, simultaneously baroque and austere, and it finds the band stretching in weird directions. For example, they cover “Nine Pound Hammer,” which had been a hit for country singer Merle Travis in 1951. Perhaps more surprising is how well they make it fit into the album’s theme.

In fact, the Beau Brummels had been peppering their sets with country covers since their first shows in San Francisco, and their 1965 debut, Introducing the Beau Brummels, included a cover of Don Gibson’s 1957 hit “Oh Lonesome Me.” They weren’t alone, either. As the “Bakersfield Sound” became more prominent on the West Coast for mixing country music with rock guitars, rock musicians were completing the circle and borrowing from country music. In 1967, Bob Dylan traveled to Nashville to make John Wesley Harding, his own stab at a kind of country-rock.

The trend culminated in 1968, when the Beatles covered Buck Owens on The White Album and the Everly Brothers released Roots. In March, the International Submarine Band released their sole studio album, Safe at Home, and five months later, the Byrds released Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Both were spearheaded by Gram Parsons, a kid out of Florida who was in love with the kind of mainstream country music that most West Coast hipsters had long written off. He is still identified with the country-rock movement, often declared its architect or instigator — and with good cause.

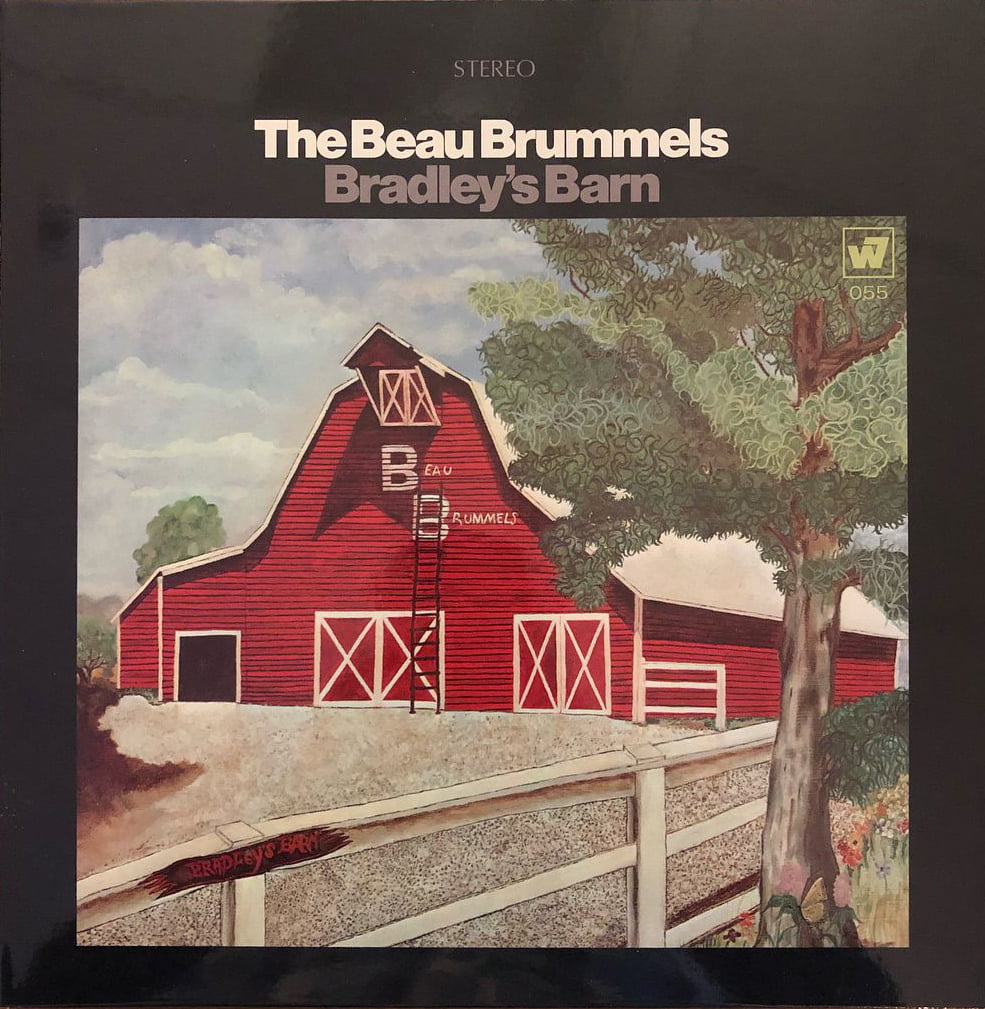

Early in 1968, at the behest of their producer, Lenny Waronker, the Beau Brummels decamped to Nashville — or to rural Wilson County, just outside of Nashville — to record a new album at the headquarters of Owen Bradley. The previous decade, Bradley had helped to define what came to be known as the “Nashville Sound,” a more pop-oriented strain of country music meant to appeal to as wide an audience as possible — not just rural folk, but urban listeners, as well. Even so long after his heyday, he would have been revered for countrypolitan classics by Patsy Cline, Brenda Lee, Loretta Lynn, and Conway Twitty.

Although it bears his name, Owen Bradley didn’t produce the Beau Brummels’ Bradley’s Barn. Instead, Waronker remained at the helm. But working in Nashville meant they had access to local session players, including Jerry Reed on guitar and dobro, Kenny Buttrey on drums, and Norbert Putnam on bass. The Beau Brummels had withered down to a trio at the beginning of the sessions and, by the end, bassist Ron Meagher was drafted into the Army and sent to Vietnam. As a duo, Elliott and Valentino were able to craft a very distinctive sound that’s more than just rock music played on acoustic instruments.

Bradley’s Barn crackles with ideas and possibilities, from the breathless exhortation of “Turn Around” that kicks off the album, to the ramshackle lament of “Jessica” that ushers its close. “An Added Attraction (Come and See Me)” is a loping rumination on love and connection, as casual as a daydream under a shade tree. The picking is deft and acrobatic throughout the album, as playfully ostentatious as any rock guitar solo, and Valentino sings in what might be called an anti-twang, an un-locatable accent that renders “deep water” as “deeeep whoa-ater” and pronounces “the loneliest man in town” with a weeping vibrato.

Bradley’s Barn wasn’t the first, but it was among the first country-rock albums. It was recorded and mixed by March 1968, when the International Submarine Band’s Safe at Home was released, but for some reason, the label shelved it for most of the year. It was finally released in October, perhaps as a means to capitalize on success of the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which hit stores in August. Once leading the way in country-rock, the Beau Brummels were suddenly playing catch-up. And yet, compared to those two Parsons-led projects, Bradley’s Barn feels like much more of a risk, less self-conscious about its country sound. Safe and Sweetheart were primarily covers albums, with only a few of Parsons’ originals and a handful of Dylan compositions. Their purpose was to define a sound, to translate hits by Merle Haggard, Johnny Cash, and the Louvin Brothers into the language of rock ‘n’ roll. As such, they’re landmark albums, showing just how malleable rock ‘n’ roll could be — how it could stretch and bend to accommodate new sounds and ideas.

Save for the Randy Newman tune that closes the album (and was recorded in L.A. right before the Beau Brummels went to Tennessee), Bradley’s Barn is all originals, each one penned or co-penned by guitarist Ron Elliott. He has a deceptively straightforward style, evoking complex emotions with simple words. Alienation and isolation are his favorite topics, which lend all of his songs, but especially this album, its distinctive melancholy. “Every so often, the things I need never seem to be around,” Valentino sings on “Deep Water.” “Every so often, I pick up speed. Trouble is, I’m going down.”

On “Long Walking Down to Misery,” Reed’s dobro answers Valentino’s vocals with a jeering riff, turning his yearning for love and comfort into something like a punchline. That sadness and the music’s response to it — alternately bolstering it and undercutting it — is perhaps the most country aspect to this country-rock album. Elliott, in particular, understands how country works, just as much as Parsons does or Dylan does. Every song is a woe-is-me lament, lowdown and troubled, but not without humor or self-awareness. Even “Cherokee Girl” uses the imagery that would be identified with outlaw country in the next decade.

Bradley’s Barn flopped, when it was finally released, overshadowed by the Southern California bands and generally abandoned by the label. In 1969, when “Cherokee Girl” failed to register on the pop charts, the Beau Brummels broke up. They’ve reunited a few times since then, most famously in 1975, but generally they live on in reissues and oldies playlists. “We weren’t trying to do country,” Elliott told rock historian Richie Unterberger in 1999. “We were trying to do Beau Brummels country, which was a totally different thing. But it didn’t really catch on.”