Philadelphia-born producer Steve Berlin cut his musical teeth playing R&B with some of the City of Brotherly Love's most famous sessioneers, went West to find himself a member of the Blasters and, for the last 40 years, has been the saxophonist, keyboardist, and de facto producer of Los Lobos. He's also produced a host of records for other artists, as well, from a strangely quixotic album for Clap Your Hands Say Yeah singer Alec Ounsworth to an upcoming set for one of American's best-known bluegrass bands (whose name we're not at liberty to divulge right now). Currently a resident of Portland, Berlin sat down at the city's Case Study Coffee Shop to talk about classic R&B, what it was like to produce Leo Kottke, and how the most recent Los Lobos studio record could be the last Los Lobos studio record.

I didn’t realize you were born in Philadelphia. Did the Philly soul of the late '60s and early '70s have any influence on you?

Oh my God, yeah. Huge influence. When that stuff was happening, I was, like, 16. Some of the people I was playing with in Philly, at that time, were playing on those records. Those guys are my heroes; those records, to this day, are some of the most amazing productions ever. They’re so three dimensional and so beautiful and so iconic and soulful. That had a lot do with me choosing to be a producer: "How do you do that? How do you make something that sounds that beautiful?"

And radio in Philly was so advanced. We had one of the first underground FM stations. When they came online, I was 13 and I would listen to it religiously. Great Black stations, great soul stations, great jazz stations. I was a child of that; that was the stew I grew up in. When I got to play with these musicians, it was a great place to learn because there was an extremely high standard. You had to show up, play great, and play anything. You couldn’t really say, "Sorry. I don’t that. I’m a jazz guy. Or I’m a rock guy."

So what kind of records are we talking about? Hall & Oates Abandoned Luncheonette, for example?

That’s a great record. It’s so funny you would bring that up. Literally, this morning, I was thinking, "I should find that record again. That’s such a great record." Arif Mardin produced that — that was a New York production, even though Hall & Oates were from Philly. I was talking about the Philly International stuff: Gamble and Huff …

… The O’Jays …

The O’Jays. The Spinners. Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes. Gamble and Huff produced the Soul Survivors record. I was playing with the band behind the Soul Survivors. Then they moved to L.A. and that’s how I got to the West Coast. They became Billy Preston’s band and said, "Hey, you should come out. Let’s put a band together here." So I did, back in ‘75. That band put one record out on Casablanca. So we got to see that whole circus. It was an interesting time, for sure.

I still get chills listening to Teddy Pendergrass …

Oh, yeah. You put those records on and it’s like … I still can’t understand how they did it. They’re so rich — the reverb spaces. I’m a pro. I should be able to figure this stuff out and it’s still beyond me. It’s magical.

How did you become part of Los Lobos?

Well, the band [that recorded on Casablanca] fell apart and I moved to Venice Beach and started playing with some guys down there, just for something to do. One of the bands was called the Beachnuts. We were terrible, but we were around a lot. The lead singer was this Korean guy who called himself Beachy Beachnut. He was a relentless self-promoter so we would play all weekend, every weekend. There weren’t a lot of sax players around … there were pros, but there weren’t a lot of guys like myself, who would play with just about anybody. So, just from being aorund, I ended meeting a lot of people who would go on to be part of the Blasters and X and bands like that.

I was working at a music store in Hollywood and I got a call from Dave Alvin [of the Blasters] asking if I could play baritone. And I said "absolutely" even though I didn’t. [Laughs] Luckily, there was a baritone at the music store that I "borrowed." That session went well so I ended up being in that band for about three years. When Los Lobos opened up for them one night, I became friends with them and started playing with them when I was off the road with the Blasters.

I produced a track for them that was on a rockabilly compilation. That went well so, when they got signed to Slash, I produced the first EP along with T Bone Burnett. By the end of that record, I was in the band.

How was it working with T Bone?

Complicated. It’s always complicated. [Laughs]

Should I ask you to explain that?

Uh … I’ll just leave it at that. I don’t want to be that guy.

Okay, then, rather than talking about all 900 records in your producer catalog, let’s talk about one of my favorites: John Lee Hooker’s The Healer.

Well, to be honest, I just did that as a member of the band. I had a lot to do with the production, but it’s not one you could say I produced.

The coolest thing about that record is that I was — and still am — a big Beastie Boys fan. Back before they actually got intelligent. I thought they were fascinating, sonically, really cool. So I was a really big fan of Mario Caldado, who engineered and produced those records. When we got the call to do the John Lee Hooker record, I thought, "It would be really cool to get Mario to do this record." So, I reached out to him, we met, and I told him it was going to be us and John Lee Hooker … and he was scared shitless. Here’s a guy who did multi-million-selling records going, "I don’t know if I know how do this." I said, "Of course you do. Just do what you do. Just guys playing. It just happens to be John Lee Hooker. " [Laughs] Part of it was for me — I just wanted to see how he did it, to observe his process. Like, "How do you make those great records?"

Which, of all the records you’ve done, stands out as being special in some way?

That’s an interesting question. There are a lot of them that fall under that category. I guess, like any parent, I like some of the weirder ones. I like the ones that are very odd … that didn’t really sell or anything like that … but are really close to my heart.

I did a record [Mo’ Beauty] with the lead singer of Clap Your Hands Say Yeah [Alec Ounsworth]. After [Hurricane] Katrina, they did these artist retreat kinds of things in New Orleans to raise consciousness about what was happening in the city … how fucked they were by the U.S. government, how the Army Corps of Engineers basically caused the flood … to interpret for themselves how things happened, because everyone thought it was a natural disaster.

I met Alec on one of those and we said, "Wouldn’t it be cool to do a record down here?" About a year later, we made it happen. It was Stan Moore from Galactica, who’s one of my favorite drummers on earth; George Porter [the bassist] from the Meters; Robert Walter on keys; a friend of Alec’s on pedal steel; and myself. Alec’s voice is an acquired taste, but the record was so much fun to make and his songs are really strange, really odd. But he works extremely hard at them. He’s not like some talented amateur; he’s a craftsman.

On the first song we did, the lyrics are about him falling in love with another man. [Alec’s] not gay but George is like, [Growling] "What is this shit? I didn’t sign up for this." Gradually, over the course of the day, though, he figured out this is great music, that it was going to be cool. The horn section was this group called Bonerama, this group of four trombone players. The other day, I was trying to talk this other band into hiring them. Since they're all over the Alec record, I had to listen again. And I thought, "Wow, this is a really great record. It’s really powerful, really emotional." So that’s one that I love.

I did a record with Leo Kottke [Great Big Boy] that I really love. I got approached by his label, who wanted to do a record of him singing. But he’s a very reticent singer; he doesn’t really like it. It was interesting to work with him in that he hears music in a very different way. We would agree that this particular sound is an electric guitar or a piano. But he hears things more in colors. He would say, if he hears anything in a certain range — something like 40hz down to 800hz — he can’t do anything, as if it literally closes off everything else. I was like, "That’s kind of wacky." I said to him, "So you don’t work with bass players?" He said, "No, I do, but I hate them." [Laughs] So we basically did the record with just him and a drum machine, and then built it back out from there. It was a really interesting way to make a record. I had never done that before … or since, for that matter.

And he was so anti-his voice that I had to come up with a new way every day to trick him into singing. We’d be packing up and I’d go, "Hey, Leo, would you mind putting a scratch vocal on this thing so I can do a rough mix on it?" I could never allow him to think he was singing. It always was, "Can you do me a favor? Just before you go. You don’t have to take your guitar out. Leave your jacket on; just run through this." That was how we did the whole record.

The psychology of being a producer …

I don’t think I’m particularly good at that part, but I’ve worked with master manipulators.

When I talked with Dave Cobb about producing Jason Isbell, we talked a lot about Bridge over Troubled Water and Roy Halee, whom he considers to be one of his big influences. Also Jimmy Miller.

Jimmy Miller is a true unsung hero. He was at the center of so many unbelievable records and nobody gives him enough credit. People never talk about Jimmy Miller the way they talk about T Bone, for example. I guess he missed out on the cult of personality part of the game. But, my God, that guy worked with Traffic, the Stones, you name it. Bob Johnston is another guy, making all those folk records in the '60s. It’s amazing. There are so many seminal guys that nobody mentions even though they’re literally the architects of modern music.

Is there a Steve Berlin aesthetic? A legacy of some sort that you would like to see passed on to the next generation of producers?

I learned this going from producing my band to being a band member: It’s never worked for me to have a sound that I bring with me. You can’t take this trick that worked once and plug it in over here and expect it to work the same way. What I’ve come to practice is to walk into a session with pretty extensive notes that no one knows but me, but not with an idea that I’m going to do something a certain way. Every project is a new thing — every song, every track. That’s what makes it fun. And, for me, it’s healthier.

When you look back at producing the first Los Lobos EP and then look at producing the latest one [Gates of Gold], what’s changed?

Well, number one is that I didn’t produce the new album. It says "Produced by Los Lobos." Normally, as part of Lobos, I would do a lot of the same stuff I would do as a producer but, really, it works best when it’s collegial. We work best without a leader. When you get to 40+ years together, nobody wants to hear from anybody what he oughta be doing. On Gates of Gold, in particular, I made a conscious effort to just let shit happen. I was the instigator on a lot of stuff on other records but, on this one, for whatever reason, I felt it was important for people to have more of an emotional investment in this record. So I was one-fifth of the hive mind that created it. There were a lot of choices made that I was on the losing end of and I’m fine with that.

It was a hard record to make, on a lot of levels. What made it hard was that everybody had to step up and make choices on their own. It was a challenge for some guys because they’re just used to going with the flow. You know — "You figure it out. I’m just going to go back home and watch TV or whatever." So, it was tough and it took a long time because, in some cases, the guys didn’t want to make choices. They just wanted someone to tell them what to do. And I thought it was important for everyone to be invested, not just saying, "Well, that was Steve’s call or that was the engineer’s call."

In terms of what has changed over the years, there are a lot of lessons we’ve learned. Number one: We’re a bunch of guys who get bored easily and, when we’re bored, it’s not good. So, one way to keep us from being bored is to not really know what’s going on before recording. We never rehearse before going in to do an album — there's almost no sharing of any demos, there’s no discussion prior to the first day or even once we start, to be honest. It’s sort of like, when you show up, you just have to jump on the boat and ride through the rapids and just go with whatever happens. Sometimes that's easy, like in the '90s when we did Kiko and Colossal Head. As I look back, they were incredibly easy records to make. Back then, you didn’t have to paddle very much; the boat would go on its own. To be honest, the last three studio records have been a lot of paddling, a lot of swimming upstream.

Frankly, I don’t know if there’ll be another one. It’s hard for me to imagine, at this point in our career, the rationale for doing another one. Where we’re at now, where our fans are at. Do we need another record? I don’t know.

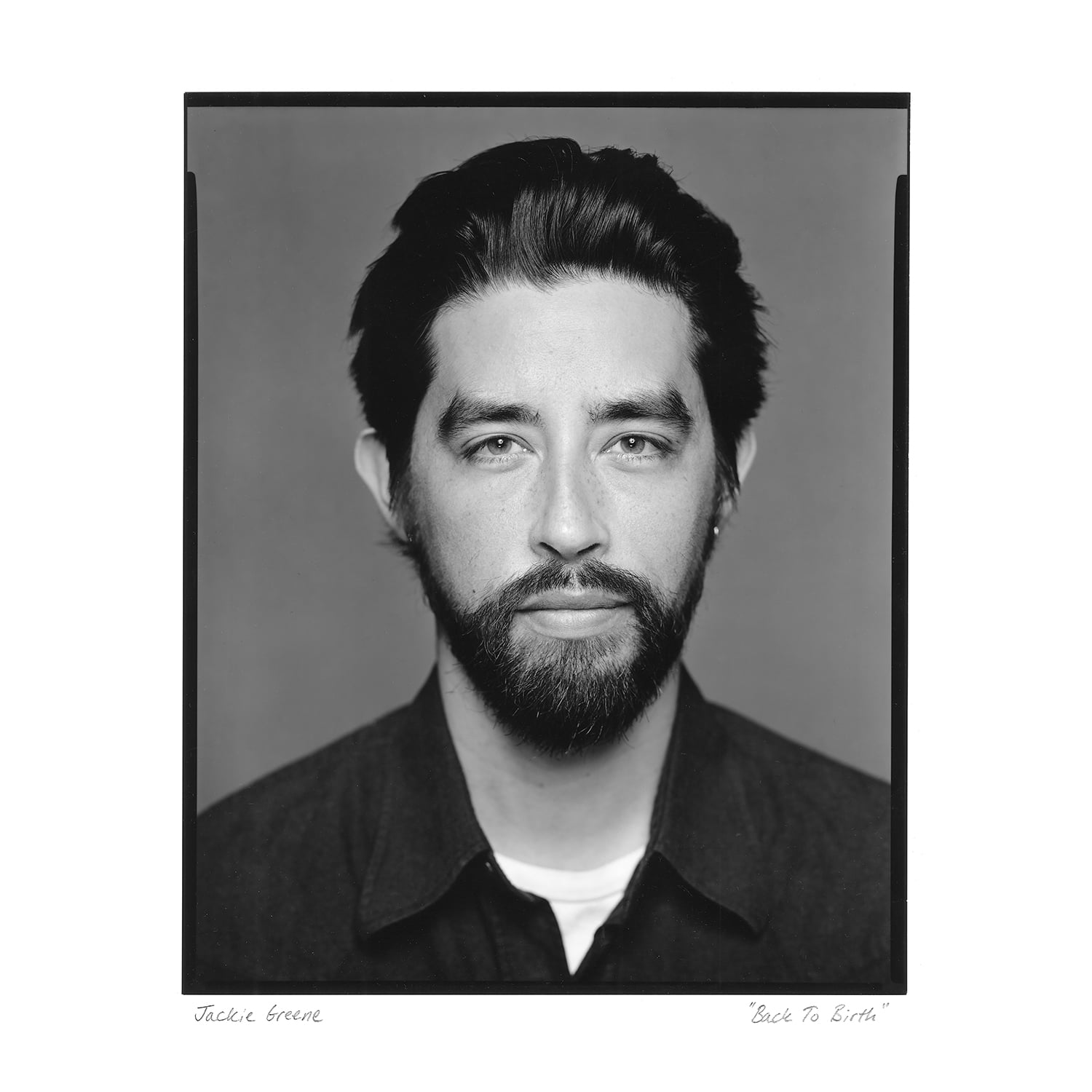

Photo of Steve Berlin at the Portland Waterfront Blues Festival, 2014 by Michael Verity