I’d be willing to bet that, if you spent a day in New York City asking strangers to name a bluegrass song, seven out of 10 would look at you funny and walk away. The other three would say “Rocky Top.” It may be a mystery how any song permeates the popular consciousness to that depth, but my theory is that “Rocky Top” had one very unmysterious special ingredient: Bobby Osborne’s voice.

In a genre synonymous with “high, lonesome” tenor singing (See Monroe, Bill; Stanley, Ralph; Flatt, Lester; and McCoury, Del) the fact that Bobby Osborne’s high notes can turn heads and drop jaws is, itself, impressive. Even better, his bio skims like a Marvel comic origin story for the ultimate bluegrass musician. Born in rural Kentucky, he grew up helping his dad stock his granddad’s general store and absorbing the songs on the Grand Ole Opry, eventually dropping out of high school to form a band with his brother, Sonny. Within a few years, he had played in bands with the Stanley Brothers and Jimmy Martin, and on bills with Flatt & Scruggs and Bill Monroe. At age 16, his voice changed: It got higher.

By 1964, the Osborne Brothers were members of the Grand Ole Opry, shorthand for country music royalty. Their calling cards were Sonny’s banjo playing, Bobby’s mandolin playing, and a slight adjustment to Bill Monroe’s formula for bluegrass trio harmony: Instead of jumping up to the tenor harmony for choruses and giving someone else in the band the melody, as Monroe did, Bobby sang the melody on top in tenor range. Monroe’s high tenor gave his bands’ harmonies a magnetic intensity and rawness — but the melody had to be traded to another singer. Bobby’s version allowed the audience to follow him on melody, from verse to chorus, right up to the stratosphere. His high tenor gave choruses a sense of lift-off.

No one can be better than Bill Monroe at bluegrass harmony. He invented the sound. It’s more like Michael Jordan and LeBron James: a new generation with a fresh, slightly higher-octane version of the formula.

Take “Rocky Top,” for example. (Please, take it.) There may be better examples, but I think it’s instructive to confront the cliché case in point. Despite its borderline parody lyrics and the kitschy associations it’s gathered in the intervening decades, it’s still a great example of the recipe that made the Osborne Brothers — and bluegrass, as a whole — exciting.

On first listen, “Rocky Top” sounds like the record player is on the wrong speed. Blazing fast banjo, a mandolin break that almost goes off the rails, and a voice — very high, so high you have to squint your eyes and turn your head to take it all in, but also effortlessly high, beautifully high, somehow competing with the banjo for the status of most impressively piercing element of the song — a voice that makes your brain search the animal kingdom for comparisions, because those notes shouldn’t be possible for a human, certainly not a human male.

Here, it’s important to stop and consider the historical trajectory of bluegrass: When “Rocky Top” hit the country charts in the late ’60s, what we now call “bluegrass” music was still really young. Hardly 25 years had passed since 1945, when Earl Scruggs joined Bill Monroe on the Opry and kids around the South gathered around their radios to hear the Blue Grass Boys. Their sound was new and wild and intense, and it made perfect sense in those heady post-WW II days of new technology and American optimism. Scruggs’ banjo was a musical hot rod, fast and loud and metallic. Bluegrass had a moment of pop culture enthusiasm. Then rock ‘n’ roll stole its thunder. Louder, brasher, groovier — the same recipe, to be sure, but a better vehicle for the energy and anxieties of the era. (Still, listen to Chuck Berry’s guitar intro to “Jonny B. Goode” or Elvis’s “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” Would any of it have been possible without Monroe?)

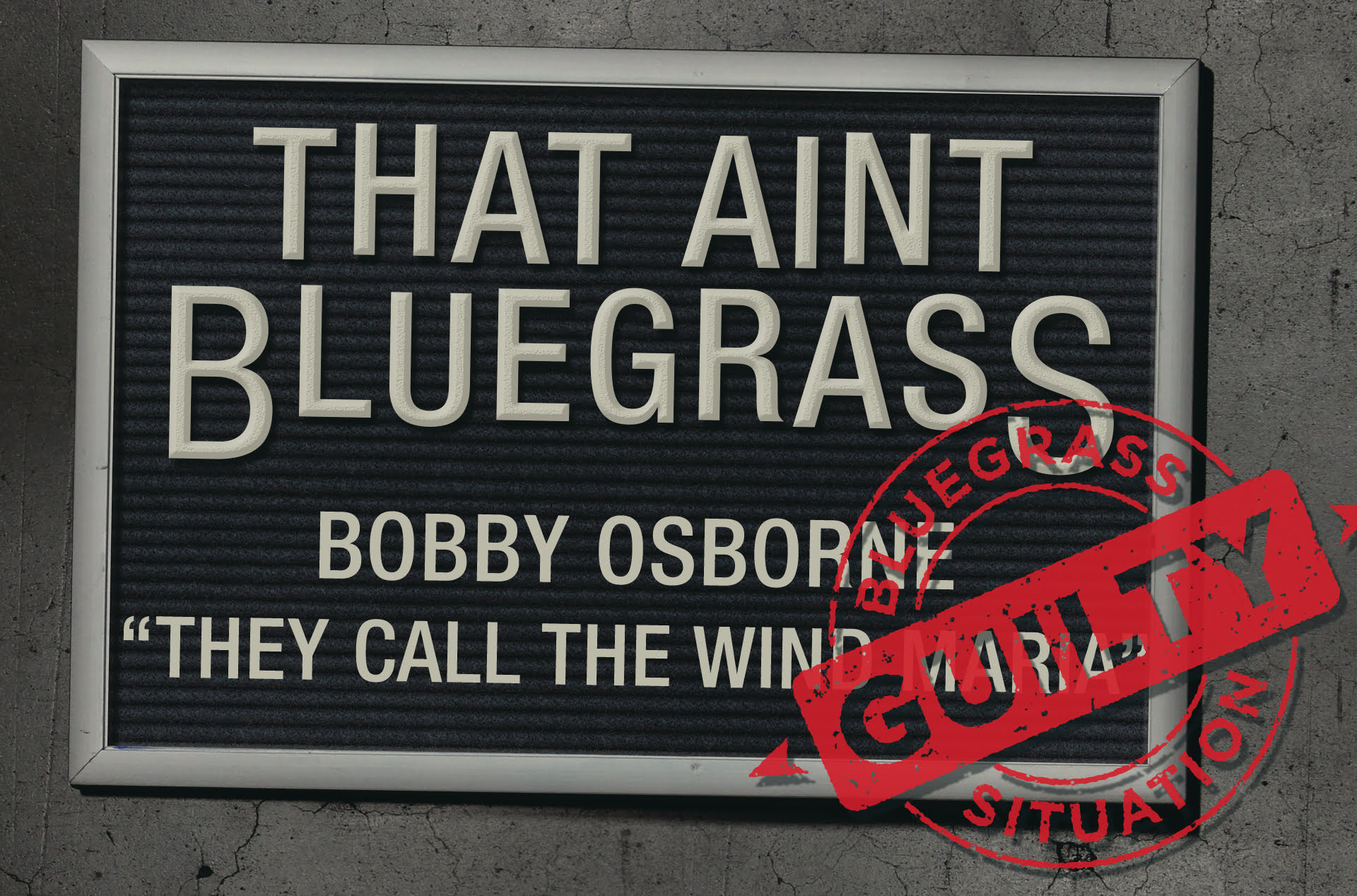

The 1950s were the lean years for bluegrass. In the shadow of rock and electric country music, acoustic bands inspired by Bill Monroe chugged along, barely making ends meet. Then, thankfully, a new musical movement swept cities and college campuses across America. The Folk Revival considered bluegrass, if not exactly old, at least a sort of stepbrother to the blues and ballads and fiddle music that was unassailably, organically American. It passed the authenticity test. In other words, 1945’s hot rod of high-flying testosterone had become, by the 1970s, traditional and worth preserving. Bluegrass, thereby, gained a capital B and became its own community, its own brand. It wasn’t just a branch on the country tree anymore; it had become its own genre with its own heroes and hierarchies and rules. Point being: By the time the Osborne Brothers got famous — not just Opry famous, but “Rocky Top” famous — bluegrass had done a lot of growing up and settling down. So, when they added drums and pedal steel and string sections to their recordings, there were plenty of folks ready to offer a cold shoulder or a brisk “tsk tsk.”

To their eternal credit, Bobby and Sonny just kept doing their thing, as they had been doing all along, like when they performed a new Elvis song on a country program in West Virginia … in 1951. To them, music was music, whether bluegrass, rock, or country. Bobby heeded the example of older musicians (see Monroe, Bill) who made recordings they wanted to make and sang what suited their voice, no matter whether their peers sounded different.

Which brings me back to “Rocky Top.” Just as it’s a shame for any musician’s multi-faceted, decades-long career to be reduced to one song, it’s a shame for the praise of a remarkable singer to be reduced to genre-specific superlatives. Bobby Osborne isn’t just a great bluegrass singer. He’s a singer — like Roy Orbison or Freddy Mercury or Robert Plant — who can, at his best, make you stop what you’re doing, turn up the radio, and wonder how the hell someone can make that sound.

Would you tell me a little bit about Alison Brown and how she put the record together?

I’ve known of her a long time as a banjo player. The first time I ever seen her was out in Telluride, Colorado. How I got acquainted with her was through Pete Rowan — I’m sure you’re familiar with him. He approached me out there in Colorado and asked me to do a song with him on a CD [The Old School, produced by Brown]. I said that would be fine. I went down there and did that, got acquainted with her for the first time. I know she was familiar with my singing for a long time before I ever met her. Time went on and I got to wondering if she would want to do a CD on me. So I just wrote to her and asked her and she said, “Yeah, I’d be interested.” Everything just sort of worked out from there.

How did you choose what songs to record? It’s an eclectic batch, from Elvis to the Bee Gees …

Well, I hadn’t recorded for a while. First of all, she said, “You start picking out some songs you’d like to sing.” I really didn’t know what to put down. So I just put down some country songs of Merle Haggard and George Jones and Don Gibson. Then I went down to that meeting, and she started pulling out brand new songs I hadn’t ever heard before. And I liked every one of them! That was the thing about it. She figured out, with the way that I sing, that those songs would suit me. Being a producer, I guess, that’s the sort of thing you learn how to do when you’re going to produce a CD on somebody. I just liked every one of them. “Kentucky Morning” and “Eight More Miles,” practically every one of them.

There are a lot of great young players on the record. Sierra Hull and Trey Hensley. Were you introduced to them for the first time? There are also some folks who’ve been around a long time like Rob Ickes and Stuart Duncan.

Well, I knew Rob. I’d never met Trey Hensley. Or I might’ve met him and forgot about him. Most of them I knew just from knowing them, not by being around them. Buddy Spicher, I knew him as well as I knew anybody, because he’d been on a lot of sessions I’d been on. Sierra [Hull], I met her once on the Opry. She’s turned out to be such a great player and singer.

Another young player taking the mandolin into great territory.

She plays what I think of as today’s style of mandolin playing. She plays it and she plays it good. My style of mandolin playing, it isn’t over the hill or anything, but it’s not like they play today. So Alison got her to play the mandolin. She was on “Kentucky Morning” and “Got to Get a Message” and we did some harmony on “Country Boy.” Then she got Del McCoury and his two boys, Ronnie and Rob. I played some harmony with Ronnie on “Goodbye Wheeling.” Then Sam Bush came in and played mandolin on “Eight More Miles.” So Alison had mandolin players and guitar players … and when we were getting songs together, I remembered way back in 1951 when my brother and I were playing up in Wheeling, West Virginia, on that jamboree, Elvis came out with “Don’t Be Cruel.” At that time, we hadn’t thought about bluegrass being different from anything else. We were just singing any kind of song. So we started singing “Don’t Be Cruel.”

You mean even back in the ’50s you were singing bluegrass versions of Elvis?

That’s right. Then right out of the clear blue sky, I told Alison, I said, “You may not believe this, but my brother and me were singing ‘Don’t Be Cruel’ back when it first came out.” She wrote me right back and said, “That’s the one I want you to do!” That suited me because I’ve always liked that one. She said, “I’ve got an idea on that.” She said, “All I’m going to use on that one is bass, mandolin, and guitar.” I thought, “What can you get out of just three instruments on a song like ‘Don’t Be Cruel?'” But that’s what she used. Sam Bush played mandolin on that, Jim Hurst played guitar, and Todd Phillips played the bass. I don’t know how she knew to do that, but she knew more about sound than I did to think of that. And she got the same sound, with a little echo in it, that they used back then with Elvis Presley.

I’ve heard Sam Bush say that in the late ’60s and early ’70s, you were his hero and that the Osborne Brothers were the kings of progressive bluegrass. There’s that great video of the Camp Springs festival in 1971 when the Osborne Brothers played alongside young Sam Bush and Tony Rice in the Bluegrass Alliance. What did you think of those young kids playing bluegrass? Did you have a sense they’d be important musicians?

Of course, back then in the ’70s — it’s a different bluegrass we have today than we had then, for sure — Sam Bush and Bluegrass Alliance had kind of a rock beat with bluegrass. But since they were programmed as bluegrass, well, Carlton would have just about anybody on that festival. They were different from anybody else. Sam played just about the same style he plays now, I guess. I met him then, but I never did get acquainted with him until the years went by, worked on a lot of shows with him, talked to him at the Opry. He’s a guy who can play like Bill Monroe or he can play like me or like Jethro Burns. Whatever type of mandolin is called for, whatever anybody wants, he can play it.

Before Sam Bush, you were one of the first mandolin players to expand the style outside of what Bill Monroe was doing. You mentioned playing Elvis songs in the early ’50s. How did you go about becoming an original player and forming your own sound?

Back when I first started trying to learn how to play, the guitar was the main thing I learned first. I always liked fiddle tunes for some reason — “Sally Goodin” and “Fire on the Mountain,” things like that. I wanted to be a fiddle player to start with, but never could do it. I’ve got about six of them here at the house. I’ve got one good fiddle — one that Kenny Baker gave me, that black fiddle he played all the time — I’ve got it. I pull it out all the time. I take it on the road and play it sometimes. But the fiddle players today, they make me look sick. I got tired of looking sick and quit playing one. [Laughs] Anyway, since I always liked fiddle tunes and the mandolin is tuned like a fiddle — and I was good with a flat pick from guitar — I got completely wrapped up playing the fiddle tunes with the mandolin. I got to following Howdy Forrester, playing hornpipes and things. I finally got into learning some of those on the mandolin, so when it came to taking breaks on songs, I kind of transferred that over.

And your guitar playing influenced your mandolin, too?

You remember a guy named Hank Garland who played the guitar? I patterned my guitar playing on his, because he was such a good player back in those days. Boy, he could play those fiddle tunes on electric guitar. I learned to do that, then I transferred that over to the mandolin. It made me different from other players. Back in those days, there was only Jethro Burns and Bill Monroe. There wasn’t anybody else to try and learn from on the mandolin. So I learned those fiddle tunes and it helped me with the mandolin. The breaks I’ve took on songs throughout the years I’ve played like a guy would take on a fiddle. And I learned a long time ago that there was only one Bill Monroe.

I read that you shared a dressing room on the Opry with Bill Monroe for a long time. What was that like?

I enjoyed it. Bill was hard to get to know. But once he got to know you — and he was another guy who figured out if he liked you or not, and if he didn’t, well, he didn’t hang around with you at all. But I got to be good friends with Bill. Been on stage with him many times. I’d have to sing the lead, of course, because he had to sing tenor. And you had to do his songs. He wouldn’t do nobody else’s songs but his. I got along with him real good. The last 15 years he lived, I shared the same dressing room with him, got to know him real good. People like him, Ernest Tubb, and Hank Snow — all of them. I really feel so thankful, the way I see it nowadays, that I was able to live in the premier day of country music and bluegrass. Bluegrass has changed so much today. But of course everything has to change. If the world didn’t change, there wouldn’t be no world after a while. But I’ve just sort of stuck to my style. I appreciate what Sierra Hull plays and the other new players do. I appreciate what they’re doing because that’s what they were brought up to do. I was brought up to do traditional.

You played with almost all of the early bluegrass players. You played with the Stanley Brothers for a while when you were young, right?

That’s right. Just before I went into the Marine Corps, for about three months, I got to play with Carter and Ralph. I loved that time. I planned on going back with them when I got out of the Marine Corps, but by that time, Sonny had learned how to play the banjo. I thought to myself, “You know, maybe we ought to start all over again.”

And that’s when you started playing with Jimmy Martin, right?

Yeah, that’s right.

I’ve heard — I mean, he was a pretty difficult guy to work with, wasn’t he?

He was a real character. As long as things were going his way, he was okay; but when it wasn’t, he wasn’t. There’s got be a bend in the river somewhere, you know? [Laughs] But Bill was kind of like that, too. But he did it — of course, Bill never did use alcohol or drugs or anything like that. He was a different type of a person. Just about all of those people — Hank Snow, too. But Hank was from another country — Canada. I mean I never did hold that against him or anything. But he was a little bit peculiar. He’d learned his way of doing things, but he was a good guy.

Who else from the Opry did you learn from?

Well, Ernest Tubb was the first guy I ever tried to sing like. And I got to know him real well. I saw Uncle Dave Macon on stage once, but I never got to know him. Uncle Dave played the clawhammer banjo. He was a show within himself. He never got on the Opry until he was about 60 years old. The Opry started in ’25, and Uncle Dave lived in those days there, when the Opry started. He wouldn’t never have no kind of band with him. And he carried about five different banjos with him at all time. He’d throw them up in the air and catch them. He was a good showman. A great showman.

So did you grow up listening to the Opry?

Yeah, that was one of the first things I ever remember hearing on the radio growing up.

So that must have been an incredible feeling, when you became a member of the Opry. What was that like?

That’s hard to explain. I dreamed about it before I even saw a guitar or anything. I dreamed about what kind of people that those guys were, back in those days — the food they ate, how they lived. I thought about all of that, all about them.

They were really the rock stars of the day back then.

Sure was. And where I come from, back in Kentucky — you know, that song “Kentucky Morning,” that’s one of the main reasons why I did that song because it tells a true story of how I grew up. I think about my dad and mom, how the times have changed. Where we lived, there was no electricity, no inside bathrooms, no running water. We had a well back then for fresh water. Nothing to wash clothes. My mom would take the clothes to the creek and pat the dirt out of them with a rock. That was the thing that really got me in the lyrics to that “Kentucky Morning.” It just brought back so much of the early days of my life. My dad and my mom, they saw times that I didn’t ever see. My dad finally wised up and moved away from Kentucky, when I was about 10 years old.

You moved to Ohio, is that right?

That’s right. He went to Dayton, Ohio. First time I saw a loaf of bread or an ice box you put ice in — see, there weren’t no refrigerators back then and very little electricity used. So we had a big old icebox. You could get a 25-pound block of ice or 50-pound or 100, depending on the size of your icebox. That was the first time I ever saw anybody put food in there to keep it cold.

So what did your father do for work?

In the Kentucky days, he taught school. He was a school teacher. And he taught school in the building I’m in right now teaching the mandolin.

Wow. Full circle.

He sure did. We lived four miles out in the country, in a place called Thousand Sticks, Kentucky. My granddad had a little store. Very few people lived in that area back there. Only way you could get anywhere was walk or ride a mule. And when the creeks were up — the roads back then went right through the creeks — if it rained, why, it was so muddy you couldn’t get over. A lot of times you just couldn’t go nowhere …

So my dad helped my granddad at his store quite a bit. It was four miles from Thousand Sticks to Hyden, Kentucky, and about once a month, he would take a wagon and mule and go across that mountain to get dry goods from a dealer in Hyden. I would go with him. I was about seven or eight years old then. But finally he got tired of that. He heard there was work in Ohio, so he borrowed 50 bucks off of his sister and went to Dayton, Ohio. First place he came to was a place called Nashville Cash Register. They gave him a job. So he came and got the family and we moved away from Thousand Sticks and never lived there again. When we went to Dayton, the big city, everything was so different then. We learned how to live in the big city. But I never did forget where I came from. I still like the country.

That must’ve taken some guts for your dad to start over and move somewhere totally different. How did you feel about it as a 10-year-old?

It hurt me in my schooling. I started going to school — they did have a school over there in Thousand Sticks. I will tell you this, too: Back during the second World War, there was work in Radford, Virginia, in a powder plant where they made powder for the weapons we were using in the war. So my dad went there and worked in that powder plant and took the family. But every time we moved, they’d put me back a grade. I was supposed to be in the fourth grade when we moved to Virginia, but they put me in the third grade. He worked there seven or eight months, and when we came back I should’ve been in the fifth grade, and had to go back in the fourth grade again there. Then when we went to Dayton, Ohio, I was supposed to be up in the sixth grade, but they sent me back in the fifth grade. So I had a tough time trying to get any education moving around like that.

Were you playing music during that time?

I was trying to play the guitar, yeah. It was about fifth or sixth grade when I got my hand on a guitar. By the time I got to the 10th grade, most people I should’ve been in class with had already graduated. So I finished my sophomore year and, by that time, I was into this music. I made up my mind right there, wasn’t no more school for me. I wasn’t going to waste my time. I wanted to put all my time into this right here, and I guess I just got lucky. So I never got any kind of education to do anything up to the 10th grade, the way I bounced around. But I will say this: I learned a lot by traveling. I’ve been in all 50 states playing bluegrass music. I’ve been in foreign countries. I’ve been in Japan two or three times, Germany, and Sweden. You get an education when you travel, if you travel enough. You learn all about different types of people, how they talk. Even starting in Kentucky, when you get to Dayton, Ohio, they have another lingo — then the Carolinas and Georgia, too. So I got a pretty good education traveling.

That might be even better than a textbook education.

I guess moving around, you learn more about the world than you would sitting still.

How did you develop your own singing style? Who did you learn from?

If you wanted to sing bluegrass, if you didn’t have a voice like Bill Monroe or Lester Flatt, you just couldn’t sing bluegrass. I lived by the Grand Ole Opry — I listened to it all the time in those days — and I noticed that one guy sounded different from the other guy. Ernest Tubb or Eddie Arnold, how different they sounded. I got tied into Ernest Tubb. I liked his songs and his singing. When I first started singing, my voice was kind of low. I could sing Ernest Tubb songs in the same key. And I had never heard anything in the world about bluegrass. The only thing I knew about bluegrass was that they called Kentucky bluegrass country. So, in listening to Ernest Tubb, I got to know all his songs.

Anyway, one day I was singing and I noticed my voice couldn’t go that low. About 16 years old, my voice just went up. And I thought, “Man, what’s happened here?” I could sing the songs, but had to put them in a higher pitch. So that put me right out of singing Ernest Tubb songs like him. Then one day I was listening to the Opry and I heard something that jumped out at me. Boy, I thought I had it on the wrong station. I heard something come through that radio and I asked my dad, “What is that?” He said, “That’s the banjo.” I had never heard of a banjo. And I couldn’t figure out how they were doing that. I kept listening every Saturday night, over and over, and didn’t hear that sound again. Finally, one night, I heard it, playing that same song, same melody as the one I had heard some weeks before that. And the announcer said, “That was Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys with Earl Scruggs playing the banjo.” That was the first sign of the word “bluegrass” connected with music I had ever heard. Then I got to singing Bill Monroe songs and I figured out I could sing them in the same key he did.

So my voice changed and went high like that. By the time I got out of the Marine Corps — I had already been playing with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in Bluefield, West Virginia, and Carter and Ralph Stanley before the military — so when I came back, I started with my brother singing Bill Monroe songs again. Flatt and Scruggs came along, and I got started singing their songs, too. But I never stopped singing country songs, either. I still sing Ernest Tubb songs today. On this new CD, I did Eddie Arnold’s “Make the World Go Away,” so I still sing country songs; I just sing them the way I feel like singing them and in my key. I guess that put me in a bluegrass class and a country class. My voice, once it got to where it was going, when I was 18 or 19 years old, it just stayed high pitch and hasn’t changed yet.

You were talking about how, even in your early days, you were playing Elvis songs and learning from electric guitar players like Hank Snow. One thing I appreciate about your music is how you always tried new sounds in the studio and new types of songs. You added drums to bluegrass early on. What did people think when you were experimenting and not trying to be traditional?

I never did try and sound like anyone else. I tried to sound like Bill Monroe at one time, and Ernest Tubb, but I found I couldn’t do that. I had a fiddle player come up to me one time and say, “Son, if I had a voice like you, I wouldn’t sing a Bill Monroe tune or Flatt and Scruggs, either one. Just sing like you feel.”

Who was it that told you that?

His name was Benny Sims. He was a fiddle player with Flatt and Scruggs, at that time. If you’re familiar with their Mercury cuts, that’s him. Yeah, we played a show with Lester and Earl, and he heard me sing. Back then, if we did a show with Bill Monroe, well, we’d sing Lester and Earl’s songs. We wouldn’t do Bill in front of him, cause that would make him mad. And if we sang with Lester and Earl, we’d sing Bill’s songs. But we worked a couple shows with Flatt and Scruggs, and of course we sang all Bill’s songs. Well, Benny heard me sing and he called me over by myself and said, “I’d like to tell you something.” He told me, he said, “If I had a voice like yours, I’d never be caught singing a Bill Monroe song or a Flatt and Scruggs song. I’d be you.” He said, “Just sing like you feel.” So I got to singing Jimmie Dickens and relying more on Ernest Tubb songs, Eddie Arnold. That’s what got me going — country songs. I’d always liked country songs. I never programmed myself to be all bluegrass or all country or all rock, or whatever. I just never did program myself any one thing, cause I could sing anything. If I wanted to sing it, I’d find the way I’d want to do it, and I’d do it.

Photo credit: Stacie Huckeba