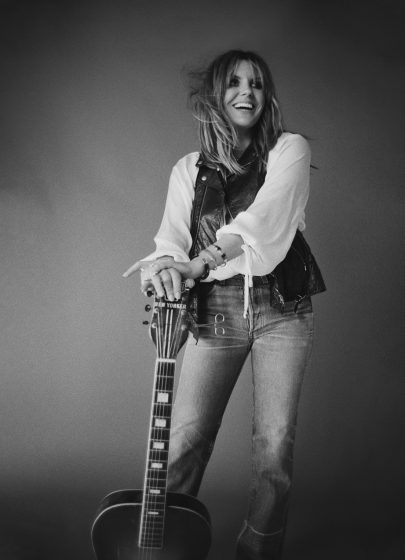

Grace Potter possesses one of the most commanding voices in popular music — which is a good thing, because on Daylight she’s got something to say.

Potter co-wrote much of the new solo album with producer Eric Valentine, with whom she fell in love while still married to a member of her band — which is now broken up, too. After their divorces, Potter and Valentine married, started a family, and now live in Topanga Canyon, California.

The overwhelming emotions of these dramatic life changes are channeled into Daylight, with many of the songs written with Valentine, and on occasion, his longtime buddy Mike Busbee, who died in September.

“Love Is Love,” a potent opener to the project, grabbed immediate attention as the first single, but in this interview with BGS, Potter goes deeper into musical pathway that ultimately led her to Daylight.

“Release” is about the aftermath of the breakup. Who was the first person you played that for when you finished it?

Grace Potter: Eric. Busbee actually texted it to Eric but it was only half the song. Our voice recorder cut off before we finished. But he just wanted Eric to hear where we were at with the writing and Eric had to pull over the car because he was bawling listening to it. And Eric doesn’t cry easily. So that was a really important moment and one that I didn’t expect.

That song, I’d started it myself in the bathtub and it had sat in my voice memo bank for like a year and a half before Eric had heard it and was like, “Let’s not sleep on that one. Let’s pursue that and see where it goes.” Obviously it went and went and went and it’s definitely the one that gets under my skin, every time. It’s hard to play live actually.

And you’re setting yourself up as the character that set this all in motion, too.

Yeah. “I know that I caused this pain…” And that really is the full taking ownership and being accountable for your choices and knowing that those choices are not always this self-righteous, “I can do no wrong” thing. Humans are vulnerable. Humans do make mistakes. Humans change their mind. Lives and careers and happiness and financial fortitude – it all shifts and changes over the time that we live. And the more I’ve lived, the more I realize that it’s okay to give yourself permission, to be that vulnerable.

You quoted the opening line to “Release,” and the opening line on “Shout It Out” sets up that song’s storyline, too. I’ve always thought that those opening lines are something you do really well, but I didn’t realize until researching for this interview that you went to film school.

Oh yeah.

So I’m curious, do you think there’s a correlation there? Because when you make a movie, you have those establishing shots in the beginning, and in your songs you have those establishing opening lines.

And sometimes I like to mislead. I like that opening line to take you in, like, a Quentin Tarantino direction. But it’s actually like a Nora Ephron romance. But I really love storytelling. It’s the same thing I do when I’m writing my sets too. Every single song and every musical experience has to take you on an emotional journey. So there’s a launch point and there’s a revelation, which you know, within the first 20 minutes of a movie, you’re always supposed to basically set up the premise of the movie and potentially introduce one twist. For me, my life was full of so many twists while I was writing Daylight that it wasn’t hard.

After the Nocturnals ended, you had to start a band again. What’s an audition process like to be in your band?

I just want to be around people I like first. Then hopefully they’re good at music. For real. Life is too short to be in a band with people that don’t fit into your ethos or feel, or just don’t feel right. You get these feelings, you get a sense when you’re in a room with someone, if they suck the air out of the room and they have that negative energy, it really changes your entire life and your entire demeanor.

You can feel yourself going kind of gray. I call it the Eeyore effect. You know, it’s this “uhhhhh” feeling. So I generally avoid Eeyores. Although an occasional well-balanced, calm person who doesn’t talk all the time is a wonderfully welcomed part of the road because we can’t all be psychotic extroverts. It’s enough with just me and my baby. But I really enjoy finding musicians who specialize in something that’s just one step quirkier than what you would expect.

Busbee, what I loved about him was that not only was he an amazing songwriter, he played the trombone. Just randomly, like, “I studied trombone.” Really? Eliza Hardy Jones, my keyboard player and singer in my band, is a next level, Olympic champion quilter. Quilting is her thing. She’s actually got a huge show in 2020. She’s doing a massive exhibition in Nebraska at the quilt museum.

Our new drummer, Jordan West, was working for Roland demoing the audio equipment, but actually was hiding in plain sight for so many people. I was looking for a female drummer who could sing, or a female bass player who could sing, or a female guitarist who could sing. I just wanted two female voices that could do all the Lucius parts. So it was fitting the puzzle pieces together for me. Instead of auditioning a bunch of people saying, “I know exactly what I’m looking for,” I just waited until I found a flow of people that felt right. And if they happen to play an instrument I needed, then you’re hired.

Kurtis Keber, our bass player, who’s been with us since last year, came into our world through my previous drummer, Matt Musty, who is now out with Train. We miss him all the time, but these happy accidents happen where you find your people. I saw Kurtis the other day. I was like, “Kurtis, what are you doing? Are you in the studio?” He goes, “No, no, I’ve been building. I’m helping do some carpentry.” My longtime guitarist [Benny Yurco] is now becoming obsessed with recording and becoming one of those crazy studio guys — from the humble beginnings of not even using one guitar pedal to this mad scientist lab they have in Burlington, [Vermont] now.

I like jack-of-all-trades people who like doing lots of things. Those are the things that attract me to people. Their strangeness. Their idioms, their specific obsession with just the tiniest little thing. You know, loose leaf tea. You can talk for an hour and a half about loose leaf tea? I’m in, count me in.

I read the lineup of your Grand Point North festival this year and you did an acoustic set on that Sunday night. What is it about that presentation that you enjoy?

Well, Warren Haynes from Gov’t Mule has been a longtime collaborator and it’s been something that we have talked about doing because we share a joy of being musical and not really knowing what’s going to happen. And not having the stakes be so high that there’s an entire band behind you train wrecking. You know what I mean?

Usually you have to rehearse and really gain a mastery over every single song and arrangement, but when you’re doing an acoustic set, there’s so much freedom to explore. Warren’s musicality and my musicality are complementary to one another where we can take it in a lot of different directions and kind of wring out the towel different every night.

We’d done it a lot backstage and not in front of people, but we felt like it would be a cool thing to share because so many musicians, they just get out there and they run the Ferris wheel, they crank the thing up and they do the same show night after night. There’s been nine years of my festival. People have seen me play with my band. They’ve seen Warren play. He’s played three times in my festival. So I really wanted to treat the audience to a different experience.

Is part of that perspective because you went to a lot of festivals growing up?

Yeah. I came from the jam band world. Warren really ushered me into it. I was very much standing in the shadows of some amazingly talented people who paved the way for me. The festival circuit is really the only way that I was able to break out on my own and be noticed and stand out. I think it’s because of those festivals that I have the sense of diversity. I can take it in a lot of different directions and it’s more fun that way.

And if you’d go to a music festival, you’re going to hear seven, eight, ten genres of music in one place and love every single one of them. I think my instincts took me in that direction, to continue on in my career through creating in the moment, more than creating for a forever thing. …

I think none of my records have ever done my musicality justice because it’s like a high school photo album. It’s this one moment — and maybe it was a very manipulated moment that isn’t even the real reflection of what I was feeling in that moment. So Daylight was the opportunity to completely break that down, take away that premise, take away this idea of having to bottle lightning, and package it and sell it to the world. And instead have an experience. Be vulnerable and open to it and see where it takes you.

As you were talking about festivals, I was wondering, did you ever get an ear for bluegrass?

Absolutely. I grew up listening primarily to Appalachian and Celtic music, which have so many deep connections. And from my family’s record collection, I was obsessed with traditional English, Irish, and Scottish songwriting because the storytelling has these archetypes in it. It’s like the Brothers Grimm. There’s these really intense, very dark stories of women that are shape-shifting and there’s these evil goblins, and then they turn into a beautiful woman. This is a combination of fantasy and reality and love and lust and danger and war. There’s all these amazing cinematic storytelling moments in those songs.

So I grew up around that, but then bluegrass came into my world because in the festival scene, there was so much crossover. I got to meet and be in a songwriter circle early on in 2006 with Béla Fleck, Chris Thile, Jim Lauderdale, and Buddy Miller. It was such a cool lineup, pulling all these people together from all these walks of life and just playing. And it was very humbling. It made me realize I got to get my shit together, my instrumentation, because these guys know how to hold it down.

I understand that you’ve moved from Vermont to Topanga Canyon, which must’ve made your inner hippie very happy.

Oh man! My inner hippie became my outer hippie. I walked to the store two days ago in a pirate shirt with a Burberry trench coat, sweatpants, Doc Martens, and a flower crown. And I didn’t even think about it until somebody sent me a photo of it and I was like, “I did what?” That was just my usual day-to-day getup. That’s Topanga. I live and breathe that lifestyle and those people really get me.

It’s a real community too. It’s a small, small group of people. And again, I think the thing I’ve been finding that I want in life is accountability. And in a big city like L.A., you can hit someone with your car, drive away and never see them again and not really ever worry about getting caught. But if I, or anyone in town, sees anything out of the ordinary, we check in on each other. That’s how tight-knit we are, and how much we care about one another. And it’s a really, really wonderful community to be a part of.

What do you hope that fans will take away from the 2020 version of Grace Potter on tour?

You know, everything about my life has been unexpected, even to me, so I certainly can’t tell people what to expect yet because I just — every bit of it has been this ride. And as I’ve gone on as a musician, I realized that my favorite part of being a musician is inviting people into that ride with me. Instead of presenting them with a packaged thing, that is what it is, I don’t know what it is! I don’t know how this is all going to work. I’ve got a baby now and my life has fundamentally changed in so many ways. I can’t wait to see how it manifests onstage. I guarantee you there will still be headbanging, that’s for sure!

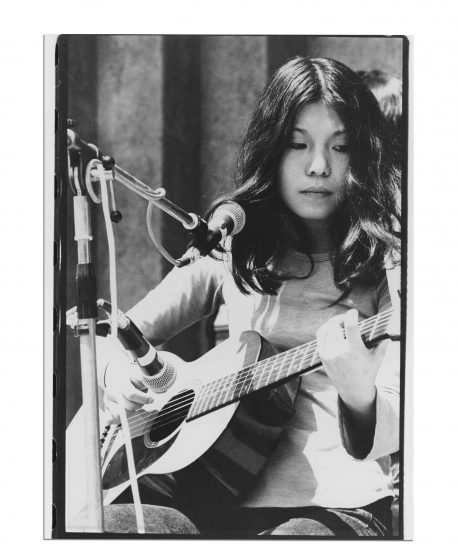

Photo credit: Pamela Neal