When it’s mentioned that the word “ambassador” comes to mind when listening to the Small Glories’ new album, Cara Luft starts to cheer. Along with her singing partner JD Edwards, the Small Glories see themselves as Canadian storytellers, like troubadours going from town to town singing about the world around them.

Truly, the Manitoba-based folk duo’s latest, Assiniboine & The Red, gives special insight into their unique worldview with songs like “Alberta,” “Winnipeg,” and “Don’t Back Down.” Chatting by phone, Luft shared a few more stories with the Bluegrass Situation.

BGS: It’s been a few year since you’ve made a record. What was the vibe in the studio when you were making this one?

CL: It was interesting in that we got everybody back together again. The only thing that changed was our engineer — and he’s a friend of ours. We had the same producer (Neil Osborne) and the same rhythm section, which was great. We actually recorded it in Winnipeg, and it was nice to be in our hometown. You know what was so funny? It was April but it was freezing cold. It was one of those moments like, “Oh my God, we live in Canada.” It’s April 15 and it’s minus 15 degrees, which is ridiculous! It was freezing! So, I remember being very cold!

This is for the Bluegrass Situation, so we have to talk about the banjo.

We do! [Laughs]

Tell me what attracted you to the banjo in the first place.

I grew up in a folk-singing family. My parents were a professional folk duo and played music when they were younger, too. My dad is a wonderful clawhammer banjo player. He’s been playing for close to sixty years now. So I grew up listening to the banjo, never thinking that I’d actually want to play it, but I did love the sound of it. I think it was kind of inevitable that I would pick it up. And of course it’s not the three-finger bluegrass style, even though I love that style. I don’t really play that but I do love the sound of the banjo.

And I love writing with it. It’s such a different instrument than the guitar. I really was guitar-focused for most of my career. I picked up the banjo nine years ago and I found it really fascinating to change the way my right hand worked, because it’s a different movement than if you’re doing fingerstyle guitar. And just having that drone string, I find that it’s like no other instrument that I’ve ever attempted playing. It’s this beautiful string that just rings out. I found it a very interesting way to write. I write differently on the banjo than I do on the guitar, so it’s brought me into a wider perspective of songs to write, I would say.

How are the songs different that you’re writing on banjo?

I would say I’m writing more tune-based songs on the banjo. As a guitar play, I am a really strong rhythm player and I would do the odd lick here and there, you know, coming up with something, but I wasn’t really a lead player on guitar. I would do some fingerstyle stuff, in more of the realm of those folkie fingerstyle guys like Bert Jansch and John Renbourn, but not really tune-based. The banjo is definitely much more tune-based for me. I write melodies on the banjo, where I never really wrote melodies on guitar before. I would sing a melody but I wouldn’t necessarily play a melody, so it’s been really beautiful to explore this melodic writing on a banjo.

I read an interview about how you loved the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken as a kid. I was curious how that might have impacted your music.

Yeah! For me, growing up in a folk-singing family, there was music all the time in the house, whether it was listening to vinyl or listening to my parents rehearse, or listening to people play house concerts, or musicians who were traveling through town and rehearsing in our living room. So I was steeped in acoustic music from a very, very young age, whether it was live or recorded.

I remember listening to Will the Circle Be Unbroken, with the Carter Family and all these phenomenal people. There’s a track on there, “Soldier’s Joy,” with two banjo players, and one is playing clawhammer and one is playing three-finger, and to this day it’s still one of my favorite songs to listen to. I think it’s just the beauty of acoustic music and the history of acoustic music, whether it’s bluegrass or folk – and to me, the lines are a little blurred there. But that album in particular, I remember listening to it all through high school and even into my early 20s.

When I listen to “Don’t Back Down,” I can hear a sense of strength in there. What was on your mind when you wrote that song?

I wrote that with Bruce Guthro, who’s a great singer-songwriter, but he’s also lead singer of a group called Runrig, a great Scottish band, even though he’s from Canada. We wrote that as part of a collaboration where we were given the theme of writing around “home,” or what we would consider calling “home.” Bruce is from Cape Breton Island, which is in Nova Scotia, way out in the Maritime Provinces. It’s known for its musical history, but it’s also known for communities that are dying because either mining has stopped or fishing has stopped. So these people would be moving away from their communities, trying to find homes and work in other locations.

I was talking to him about being from the Canadian prairies, where there are quite a few areas in Saskatchewan that are full of ghost towns, where people have uprooted and moved to cities like Calgary or Edmonton, or Fort McMurray where the oil sands are. We were comparing notes about these communities that are dying, and what is it like for those who decide to stay? They don’t want to give up on all the things that hit them, right? They stick around during the dust bowl or when the fires come, when work has dried up and people are trying to find a way to make a living. So we thought, “Let’s write a song to honor those people who have decided to make it work in their home communities.”

Speaking of home, your song “Winnipeg” is such a love letter to your hometown. I noticed as that song progresses, there is another voice that comes in. Can you tell me more about that?

Yes, we have two guest vocalists on that track. Winnipeg has a huge indigenous population and a huge Métis population, which is a combination of people who have come from both an indigenous and a French background, and we also have a large French population, and then the English, and then everything else under the sun is in there, too.

We felt that in order to really honor our adopted hometown of Winnipeg, we needed to involve the French and the First Nations people in the song. We have a wonderful singer and songwriter who is Métis and she ended up writing a French portion to the song and doing a call-and-response with us on the track. And we invited a First Nations chanter and drummer to come and sing at the end of the song. We felt it wrapped up this beautiful multicultural community that we have in Winnipeg.

To me, “Sing” captures the spirit of this record. It lets people know about you and what you stand for. Is that important for you to share your own experiences with an audience?

Yes, I think it is. I think we’ve been more aware of bringing stories from other places that we’ve been, too, so it’s a combination of our experiences and also other people’s experiences. And with this record being released on an American label, we feel very privileged to be able to share about Canada with our American neighbors. It’s a very Canadian-focused album, with a strong sense of location. We want to bring stories about the people in Canada, and what things are like for us, and share that with the States, and Europe, and Australia, and the markets we get to go to.

It’s so great when people hear a song like “Winnipeg,” like, the people who come up to us in England and say, “Wow, I never thought I’d want to go to Winnipeg!” It cracks us up. We’re happy that we live in Winnipeg and we’re lucky that we live in Canada. We feel very privileged to live in Canada and we want to share some of the love, and some of the stories, of who we are and where we’re from.

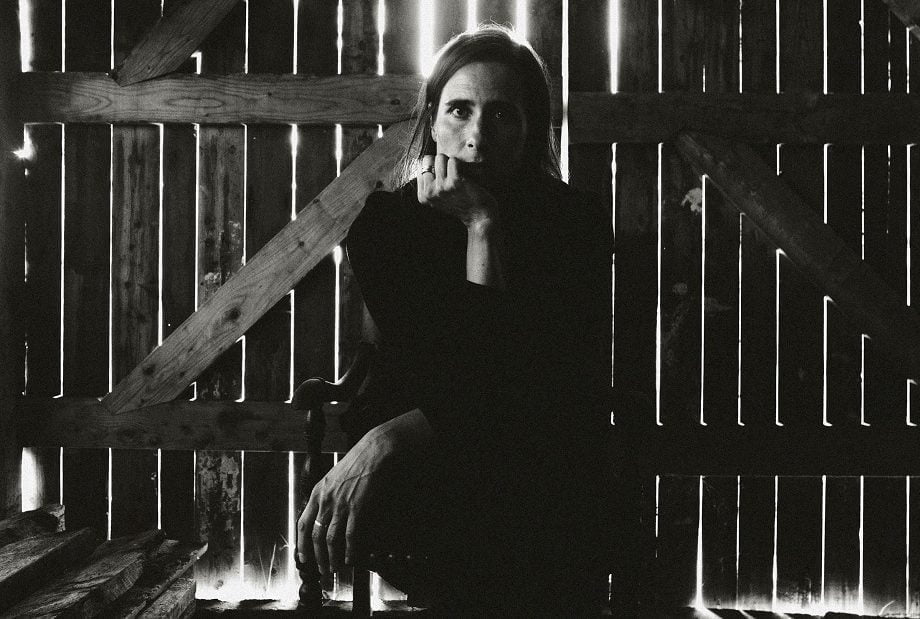

Photo credit: Stefanie Atkinson