[Editor’s Note: In September 2023, fine art photographer Erika Goldring (Getty Images, New York Times, Billboard) was on hand at Park City Song Summit in Utah to document the music and wellness event. Below, enjoy selections from her PCSS photographs and her reflections on this one of a kind gathering of songmakers.]

All in all, what moved me about Park City Song Summit was seeing artists and fans connect in a different way — more intimate shows, the opportunity to ask questions. We’re all just trying to make our way through this crazy world. Song Summit has created a community for those of us in the industry to have open and honest conversations about navigating personal struggles. – Erika Goldring, photographer

When I first heard about Park City Song Summit, I was like, “This is where I need to be!” It’s more than a music festival, it’s four days of music AND wellness! It’s a chance to take a deeper dive into the lives of the musicians I love, whether it’s hearing about someone’s creative process or what they do to maintain sanity on the road. No one is afraid to talk about mental health and recovery, and this is where the magic lies for me.

To see an artist do a solo acoustic set who doesn’t usually do that is always a treat. You know you’re getting something different. When Lukas Nelson sat down at the keyboard to do the title song of his last album, A Few Stars Apart, I got goosebumps — it felt so intimate and vulnerable. He did a few covers at the end of his set, including Pearl Jam’s “Breathe” and the Grateful Dead’s “Ripple.” I loved it, the audience loved it, we all joined in singing, and it was lovely to see him enjoying himself.

I first met Harold Owens at Imagine Recovery in New Orleans when MusiCares invited Ivan Neville to tell his recovery story. I have crossed paths with him many times since then. He’s helped a lot of people with substance abuse issues get into treatment.

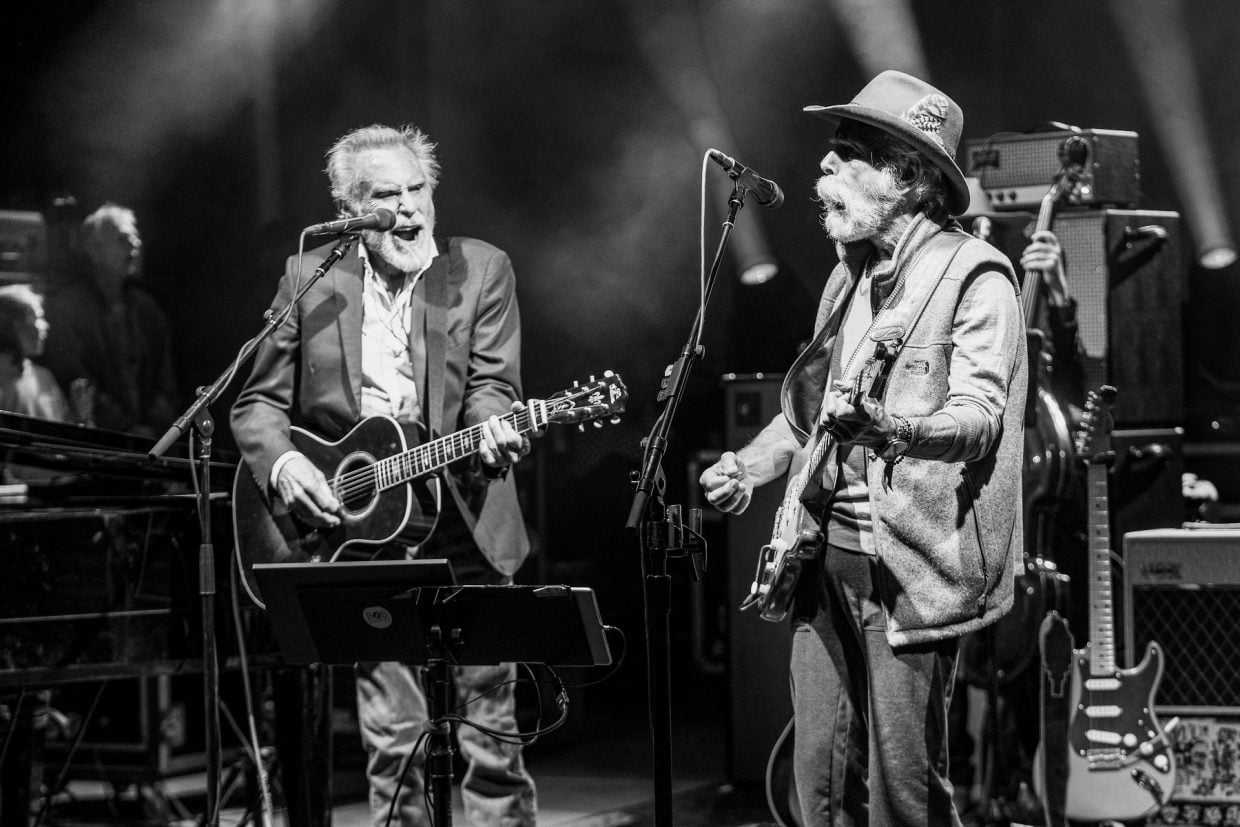

Elliott Adnopoz, aka Ramblin Jack Elliott, a cowboy folksinger. The first time I saw him was on Arlo Guthrie’s Ridin’ on the City of New Orleans tour, post-Hurricane Katrina. He’s 92 years old and still at it! He sat in with Bob Weir for a cover of Bob Dylan’s “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight.”

I was thrilled to see Caroline Randall Williams (right) announced as a panelist with Adia Victoria (left) and Celisse (center). She wrote a piece early on in the pandemic about Confederate monuments that really made me think in a different way. These are smart and eloquent women talking about the blues and loving every minute of it.

Emily Lichter has a great spirit. Not only did she speak about managing artists, but she also brought Leta Herman from Alchemy Healing Center and speaker Ruthie Lindsey to Song Summit. Hilary Saunders subbed for Marissa Moss as moderator, due to an illness, and did a great job.

I would say Steve Poltz is a stand-up comedian first and a songwriter second. He wrote “You Were Meant for Me” with Jewel. I met him about 20 years ago when he was still drinking. He’s sober now and his stories are hysterical. I left his panel with a smile on my face and then went to watch him teach people how to write songs. I have no musical abilities. I don’t know how to play any instrument and would not even know where to begin to write a song… maybe lyrics, but definitely not music. This creative process is foreign to me even though music is my life!

At 40, Danielle Ponder quit her job as a public defender to launch a career in music. She is a reminder to be brave and follow your dreams. She can command a crowd with her voice, sometimes delicate and sometimes roaring. While shooting the second photo, I saw this halo of light appear the very moment she belted out “Run!” during her cover of Radiohead’s “Creep” that ended her set.

I love a songwriter round – the joy in this hootenanny was infectious! This round featured Danny Myrick, Travis Howard, Aaron Benward and Matt Warren.

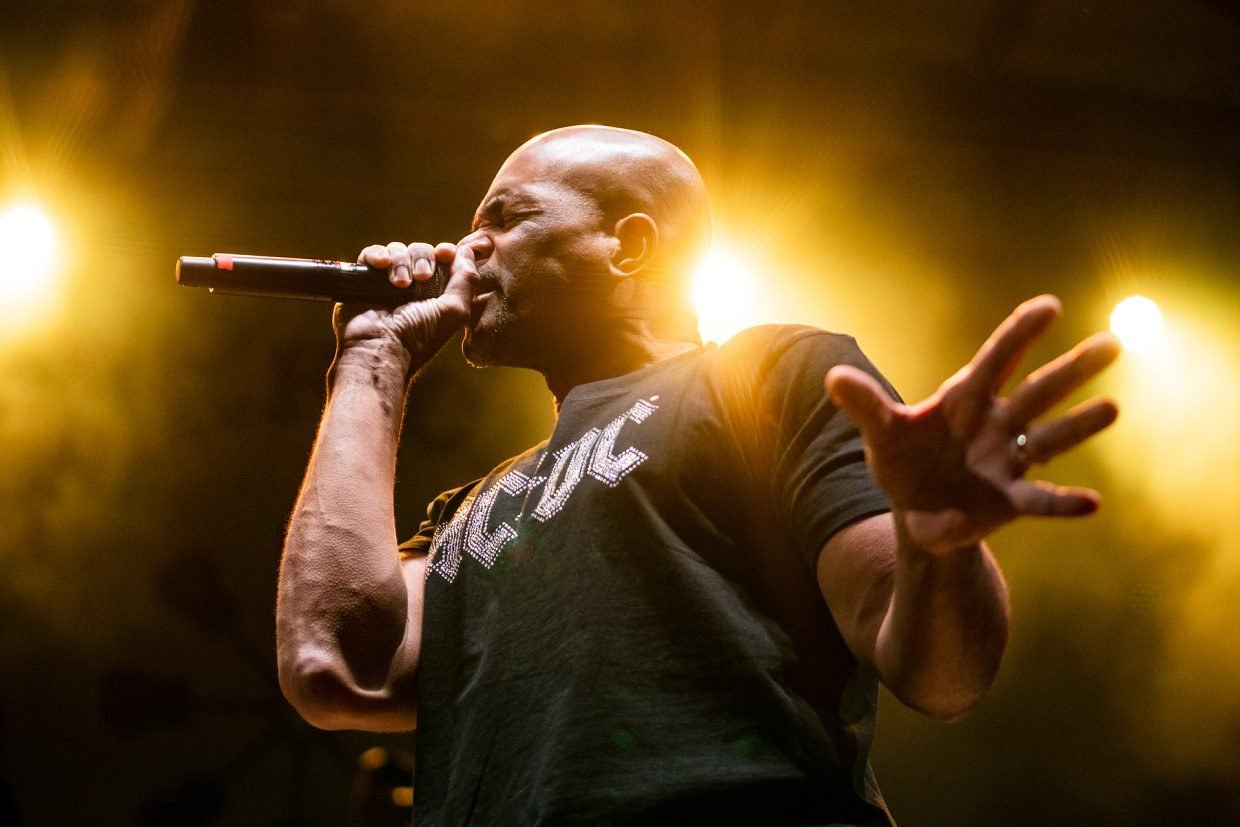

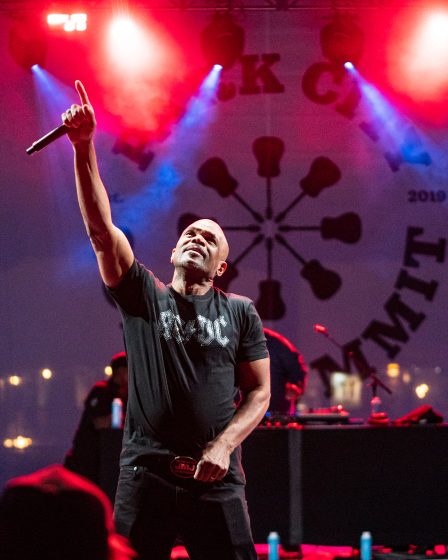

Darryl “DMC” McDaniels, half of Run DMC, was in Park City to celebrate 50 years of hip hop. While we were all watching Run’s House on TV, DMC was in rehab for addiction and depression. The first photo is another shot when I saw the light surrounding him in an intense moment of rap.

DMC and Chuck D of Public Enemy onstage discussing the first 50 years of hip hop. These two guys toured all over together in the ’80s and ’90s, so they know each other well. I loved seeing them enjoy each other’s company while talking about their hugely successful careers.

Celisse loves you. She has such a beautiful smile and she let it rip on that guitar!

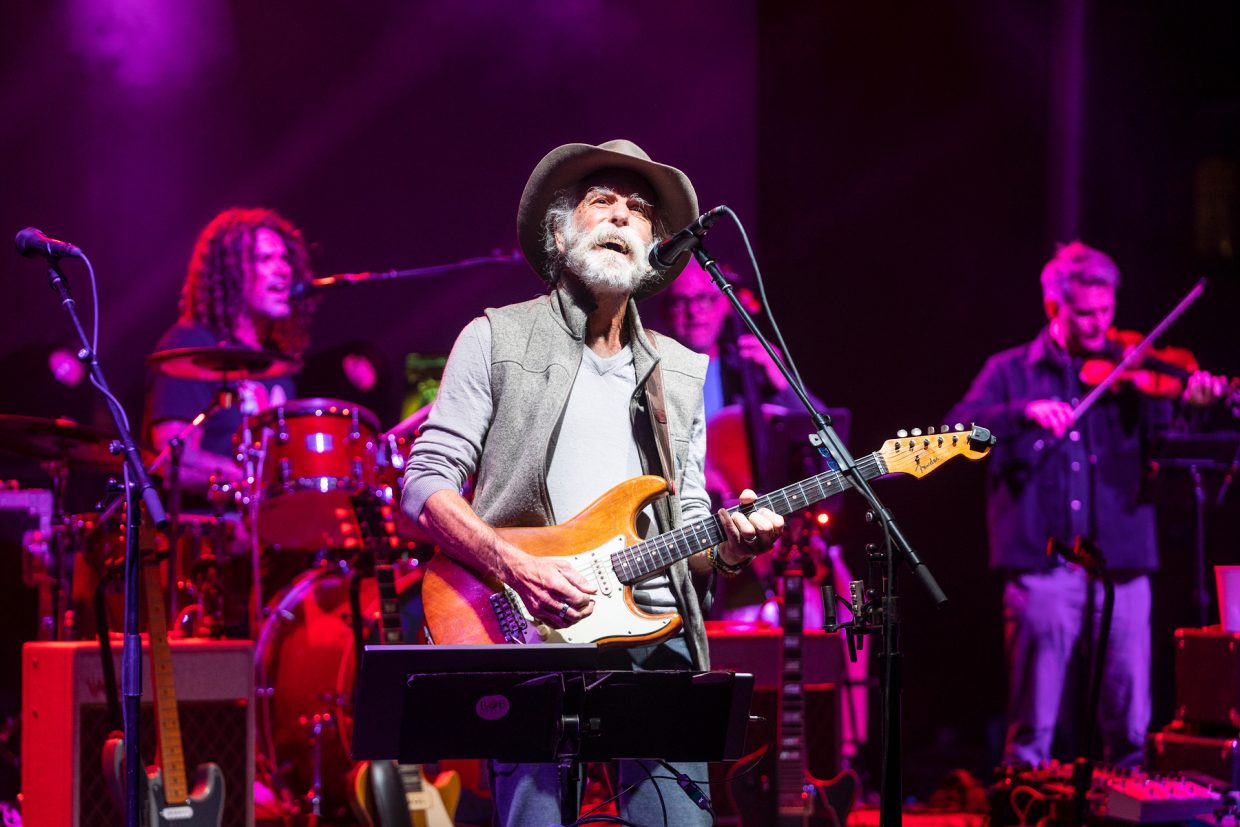

Bob Weir is the artist I was most excited to see at PCSS. The Grateful Dead were the soundtrack to my college years. I loved the album Blue Mountain and was excited to see what the Wolf Bros had in store for us on Saturday night. I love this photo, because he actually looks like he’s smiling.

The first time I saw Brittney Spencer, she opened for Jason Isbell in Detroit, Michigan. She joined Isbell and the 400 Unit to cover the Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter” and nearly knocked me on my butt. The woman is a powerhouse! She joined Bobby for “Looks Like Rain” and showed all her tender glory. It was beautiful.

JD Souther, come on! This guy wrote or co-wrote some of the Eagles biggest hits. He also joined Bobby on stage for “Heartache Tonight.”

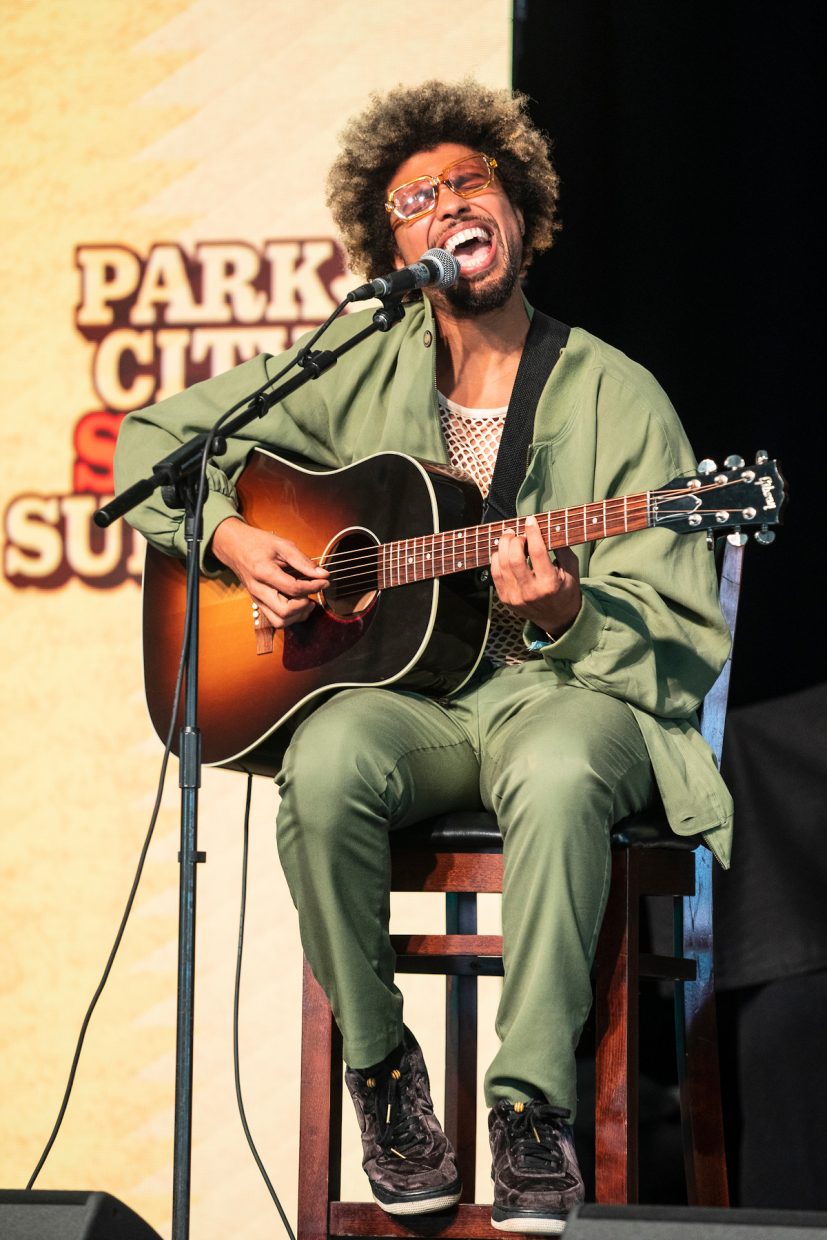

Devon Gilfillian was part of Sunday morning’s Biscuit and Jam benefitting Café Momentum, a restaurant and culinary program designed to teach teens involved in the juvenile justice system life skills so they don’t end up in jail again. Devon’s warm heart and soulful voice was a good compliment.

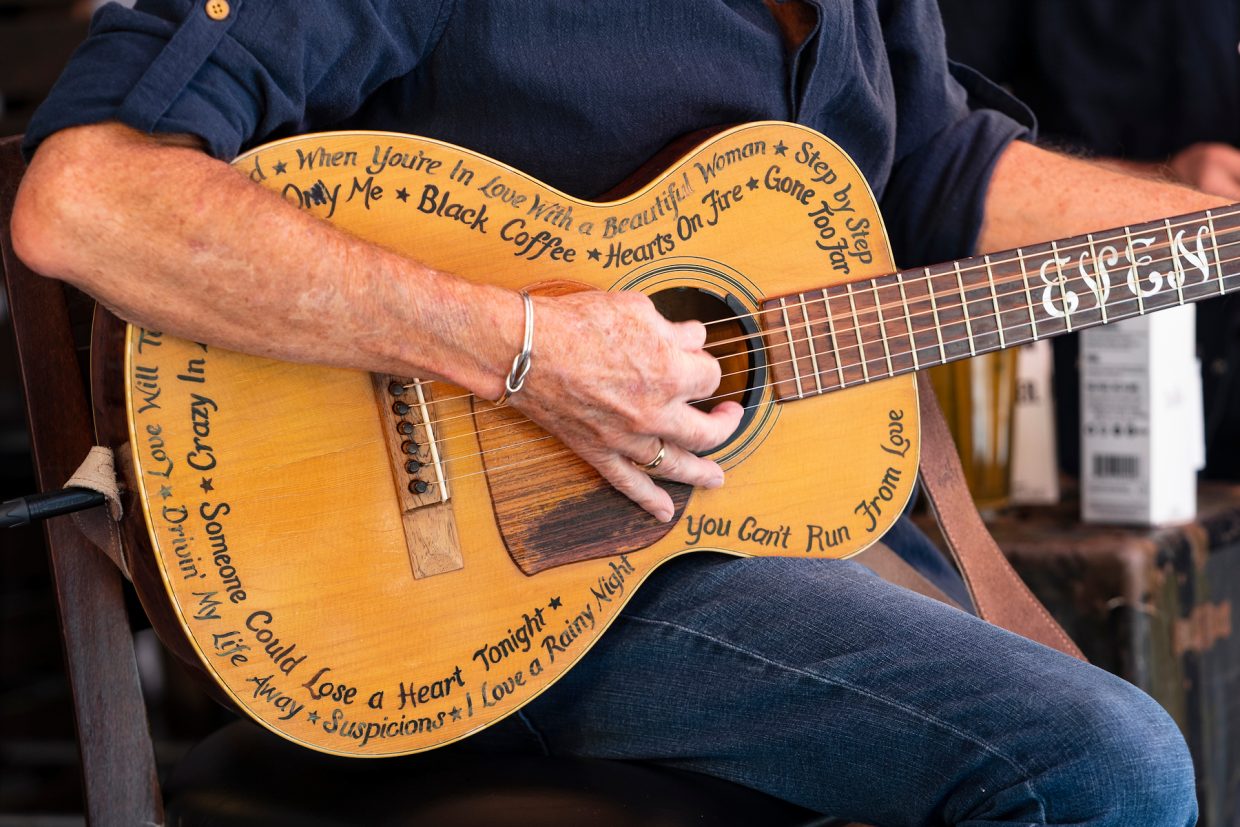

I think the only times I’ve seen Even Stevens have been in someone’s living room on a Sunday afternoon in Key West, playing hit after hit that I grew up listening to in the ’70s, many for Eddie Rabbit. “I Love a Rainy Night,” “When You’re in Love With a Beautiful Woman,” “Drivin’ My Life Away,” and “Step by Step,” to name a few. Kenny Rogers’ “Love Will Turn You Around.” Pop country classics!

Collaboration, connection. Negah Santos plays with Jon Batiste, but ended up in Park City as the guest of another participant. They added her to the Eric Krasno show on the mountain with Dumpstaphunk and some New Orleans horn players. She fit like a glove.

If you know me, you know I love Cuba and Cuban music. I’ve been traveling to Cuba for 20 years so I am always excited to see Cimafunk. The first time I saw Erik, the lead singer, was in Havana with an all-star band called Interactivo. It was March 2016 and I was in Havana to see the Rolling Stones. This band brings a mix of funk, hip hop, Cuban, and Afro-Caribbean music to the stage that will get you moving.

Tony Hall and Steve Poltz traveled all over the world together as part of Jewel’s band during the height of her career. Tony was performing with Eric Krasno & Friends on Saturday night of the Summit. It was mostly New Orleans musicians from Ivan Neville’s band, Dumpstaphunk, plus Anders Osborne and Negah Santos. I spotted Poltz in the crowd rocking out when Tony Hall stepped off stage to let Ben Anderson take over on bass. This photo is just a moment captured — two old friends running into each other. I honestly don’t think I’ve ever seen Tony smile like this.

All photos courtesy of Erika Goldring.

Lead Photo: Eric Krasno & Friends perform at Park City Song Summit 2023.