Among the many writer’s hats I wear is one of children’s music reviewer. When my daughter was in grade school, it was fun playing various kids CDs for her. She’s in college now, so those days are gone. I did keep her in mind, however, when putting together this playlist, thinking about songs that she would tolerate listening to now.

A lot of people associate children’s music merely with those simple, preschool music-time tunes about numbers, letters, and other lessons for toddlers. And there certainly a lot of those songs. But, as in any genre, there is a lot of interesting children’s music being made too.

This mixtape is a “mix” in a several ways. It mixes together songs by “adult” musicians who have ventured nicely into the family music world as well as children’s musicians with what some might call “crossover potential.” There are originals and covers. Fast songs and slow ones. And hopefully it’s a mix that Bluegrass Situation families can enjoy on an hour-long drive, whether it’s a fast drive or a slow one.

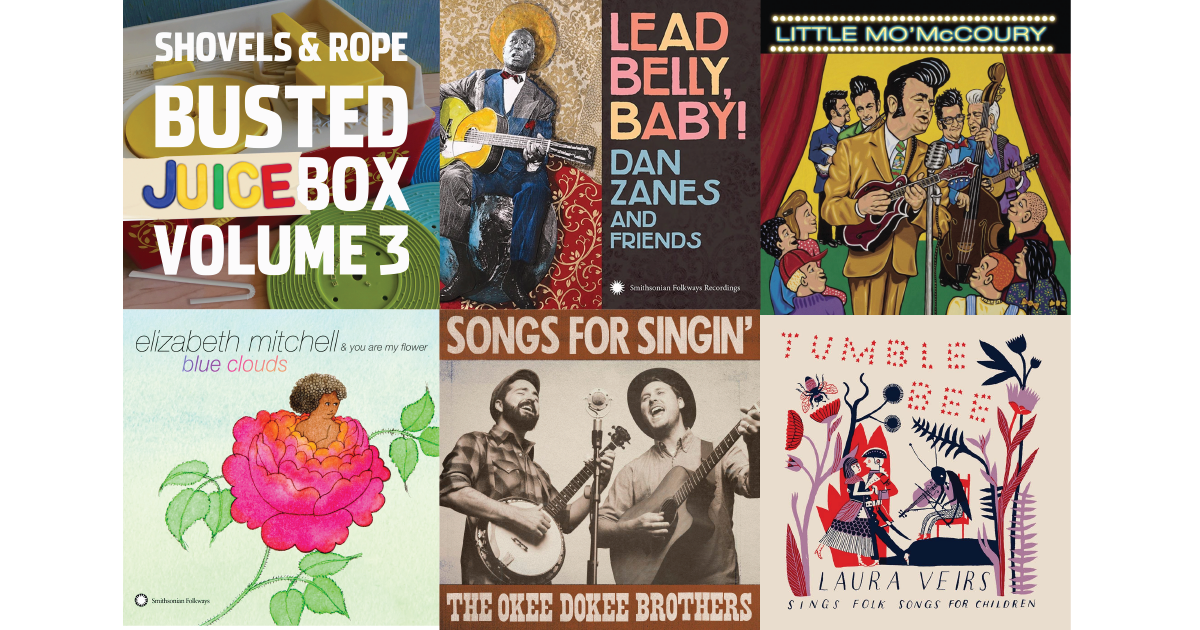

To create some parameters, I chose recordings released since 2000, only recordings made for children, and, yes, only recordings found on Spotify (I couldn’t find Jessie Baylin’s Strawberry Wind or I Love: Tom T. Hall’s Songs of Fox Hollow or else they might have been represented here). Also, I also stayed away from songs that seem to appear on every fourth children’s album (sorry, “Rainbow Connection”). — Michael Berick

The Okee Dokee Brothers – “Hope Machine”

These “brothers,” Joe Mailander and Justin Lansing, have put out a handful of excellent, old-school, folk-inspired albums that mix originals with traditional tunes. You can hear the Woody Guthrie influence in this cheery, gently philosophical original from their 2020 album, Songs for Singing. Here, as in all their music, there’s a wonderful, easy-going approach that doesn’t dumb down to kids.

Elizabeth Mitchell – “Blue Sky (Little Martha Intro)”

This Elizabeth Mitchell isn’t the actress from Lost, but the singer/guitarist from ’80s indie rockers Ida. Over the past 20 years, she has also made many terrific children’s albums, mainly for Smithsonian Folkways. Featuring nifty guitar playing from her husband and longtime collaborator Daniel Littlefield, Mitchell’s acoustic cover of this Allman Brothers classic hails from her Blue Clouds album, where she also reconceives Bowie, Hendrix, and Van Morrison songs.

Randy Kaplan – “In a Timeout Now”

On his album Mr. Diddie Wah Diddie, Randy Kaplan has great fun taking “poetic license” with old blues tunes and, in this case, the Jimmie Rodgers hit “In the Jailhouse Now.” Kids will love the comical lyrics and parents will appreciate Kaplan’s inventive, child-friendly renovations on roots music nuggets.

Laura Veirs – “Soldier’s Joy”

I read somewhere that “Soldier’s Joy” is one of the most played fiddle tunes of all time — and that it was a slang term for morphine during the Civil War. Veirs, who hails from the Northwest indie rock scene, keeps her version on the toe-tapping PG side. This duet with The Decemberists’ Colin Meloy comes from her highly recommendable, and only, children’s album, Tumble Bee.

Wee Hairy Beasties – “Animal Crackers”

This kooky side project by alt-country all-stars features Jon Langford (Waco Brothers/The Mekons), Sally Timms (The Mekons), Kelly Hogan, and Devil in the Woodpile. Pun lovers of all ages will revel in the wild wordplay running through the title track to this decidedly goofy 2006 album.

Little Mo’ McCoury – “The Fox”

Little Mo’ McCoury arguably stands as the most authentic bluegrass album for children, at least in the 21st century. Ronnie McCoury leads his family band through a set of old-timey tunes plus “You’ve Got A Friend” and “Man Gave Name to All the Animals.” While there are some overly familiar choices (“This Old Man,” “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad), “The Fox” provides a frisky workout of this bluegrass standard.

Meat Purveyors – “The Crawdad Song”

“The Crawdad Song,” along with “Froggie Went A-Courting/King Kong Kitchie Kitchie Ki-Me-O” must rank as the traditional tunes most frequently recorded for children. I included “Crawdad” here because it is the one ingrained more in my brain. And I picked this version because of the Meat Purveyors’ speedy bluegrass-y rendition. You’ll find it on Bloodshot Records’ irreverent kids’ compilation, The Bottle Let Me Down (although parents might want to listen to it before sharing with their little ones).

Red Yarn – “Rabbit in a Log”

Red Yarn (the nom de plume for Oregon-based musician Andy Furgeson) makes rootsy music that appeals to all ages. He frequently travels an early rock and roll route but he follows a more acoustic road on this hopped-up banjo-powered take of the old folk tune that appears on his Born in the Deep Woods album.

Johnette Downing – “J’ai Vu Le Loup, Le Renard Et La Belette”

Louisiana music is a popular Americana style in children’s music, probably because it so easily gets kids dancing. On her album Swamp Rock, the New Orleans musician Johnette Downing does a marvelous job presenting, and explaining, a variety of Louisiana-bred music and culture. This bilingual animal tale (“I Saw the Wolf, the Fox and the Weasel”) showcases two Cajun greats: fiddler Joel Savoy and accordionist Roddie Romero.

Kare Strong & Josh Goforth – “To The Country We Will Go”

Slowing down the tempo a bit, “To the Country We Will Go” offers a leisurely family trip. This song, as with most Kare Strong’s music, contains elements of English folk ballads. Providing the banjo, fiddle and other musical accompaniment is Josh Goforth, a bluegrass vet who has played with David Holt, Appalachian Trail, and Carolina Road.

Francis England – “Blue Canoe”

Sticking in the traveling mode, “Blue Canoe” is a charming little outing from Francis England, who makes consistently excellent music for families. This tune appears on her debut, Fascinating Creatures, an album where I would recommend “Charlie Parker” and “The Books I Like to Read” too.

Dan Zanes featuring Valerie June – “Take This Hammer”

While Zanes is right at the top of the best-known kids musicians today, I couldn’t resist including something by him. He has a whole bunch of fine tunes to choose from and I wound up landing on this one, which he sings with Valerie June, from his 2017 tribute album, Lead Belly, Baby!

Sarah Lee Guthrie – “Go Waggaloo”

I couldn’t exclude the name “Guthrie” from this mixtape. For this title track to her family music album, Sarah Lee (Woody’s granddaughter and Arlo’s daughter) wrote a song using unpublished lyrics her grandfather had written. Starting off like a silly sing along, the tune quickly goes deeper becoming a somewhat autobiographical look at Woody’s life.

Josh Lovelace with Spirit Family Reunion – “Going to Knoxville”

Lovelace took a break from his day job as keyboardist in rock band Needtobreathe to make a kids album. A standout track on Young Folks, “Going to Knoxville” is joy-filled, driving-in-a-car love song, with Spirit Family Reunion’s Nick Panken and Maggie Carson contributing some singing and banjo playing.

Beth Nielsen Chapman with Kid Pan Alley – “Little Drop of Water”

Kid Pan Alley, a Virginia-based nonprofit, sends songwriters into schools to collaborate with students. Chapman wrote this song with a third-grade class. Besides its strong message about water conservation, it’s pretty darn catchy too. My family still remembers it over a dozen years after the disc was last in our car’s CD player.

Justin Roberts – “Rolling Down the Hill”

One of the most skillful songwriters in the children’s music scene, Roberts usually operates in the pop/rock field, so this is a rare tune of his with a fiddle. Roberts injects just enough details into this playful ditty to make it resonate with both parents and kids — without slowing down the momentum.

Shovels & Rope with The Secret Sisters – “Mother Earth Father Time”

The just-released third volume in Shovels & Rope’s Busted Jukebox series is a set of family-oriented covers entitled Busted Juicebox. The husband-wife duo Michael Trent and Cary Ann Hearst partnered with The Secret Sisters for a sweetly sung rendition of this tune from the 1973 animated film version of Charlotte’s Web.

Sarah Sample and Edie Carey – “If I Needed You”

These two singer-songwriters teamed up back in 2014 to make ‘Til the Morning, a lullaby album that shouldn’t just be restricted to nap time. This Townes Van Zandt gem was a particularly inspired choice and their tender interpretation is quite moving.

Alastair Moock with Aoife O’Donovan – “Home When I Hold You”

Moock is a Massachusetts singer-songwriter whose family albums often tackle themes like inclusivity or social action. This track comes from Singing Our Way Through, an inspiring, powerful work he made for families dealing with pediatric cancer. His duet with Aoife O’Donovan conveys a simple yet poignant message of love from parents to a child.

Sara Watkins – “Pure Imagination”

Watkins’ first family album, Under the Pepper Tree, arrives on March 26, and its first single offers an appetizing hint of what’s to come. Watkins’ heavenly, soaring vocals highlight her gorgeous rendering of this Charlie and the Chocolate Factory tune. And celebrating the magic of creativity and the freedom of possibilities seems like a sweet note to leave families with.