A lush, resplendent, living and breathing album, Sam Lee’s brand new record, Old Wow, is something of a garden — and not simply because the opening track, “The Garden of England/Seeds of Love” sets such a tone. In this arboretum, Lee is collecting the most rare and fragile of cultivars — ancient folk songs. He is carefully tending them, gently fertilizing, grafting, hybridizing, and cross-pollinating them with bits of himself, bits of this global moment, and bits of this generation.

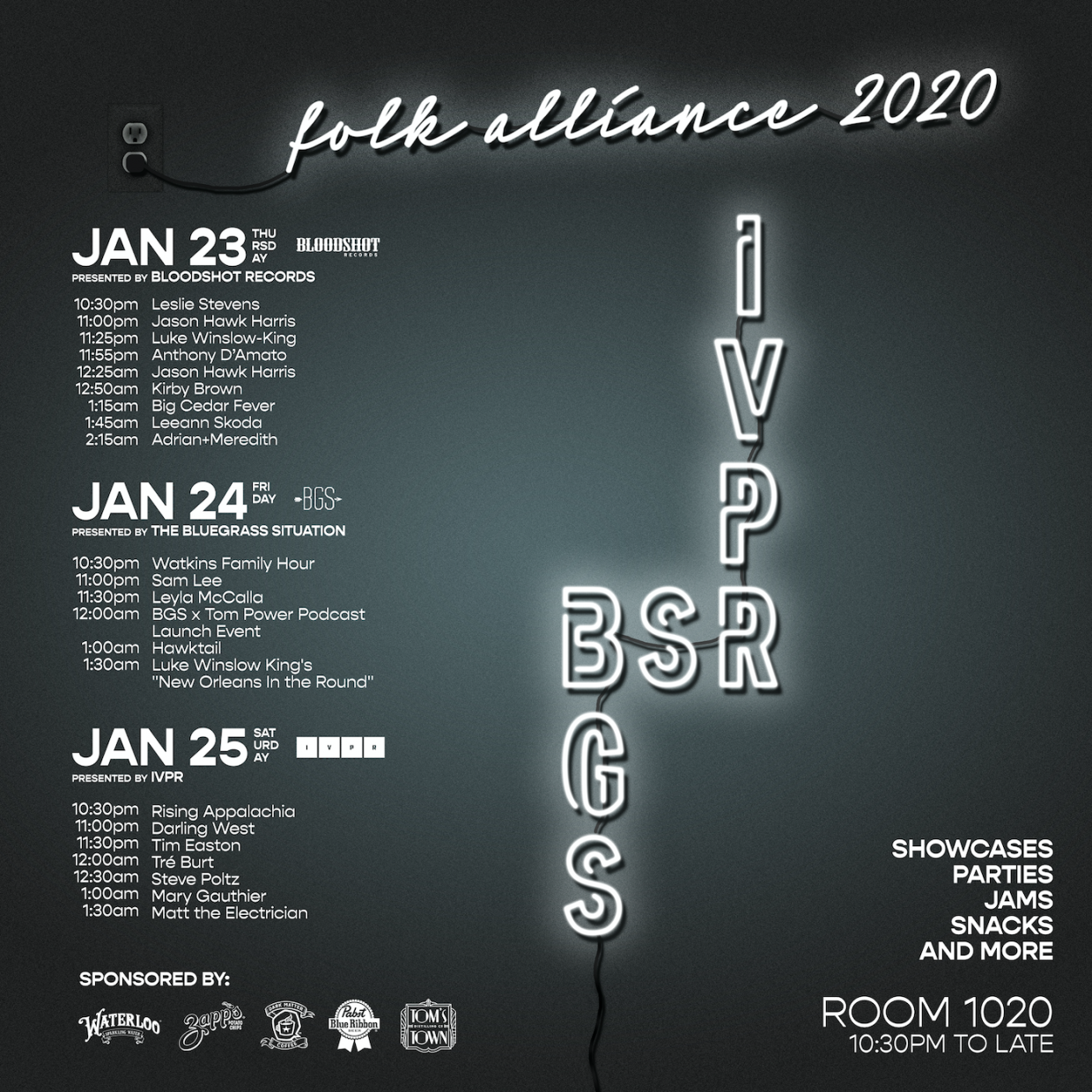

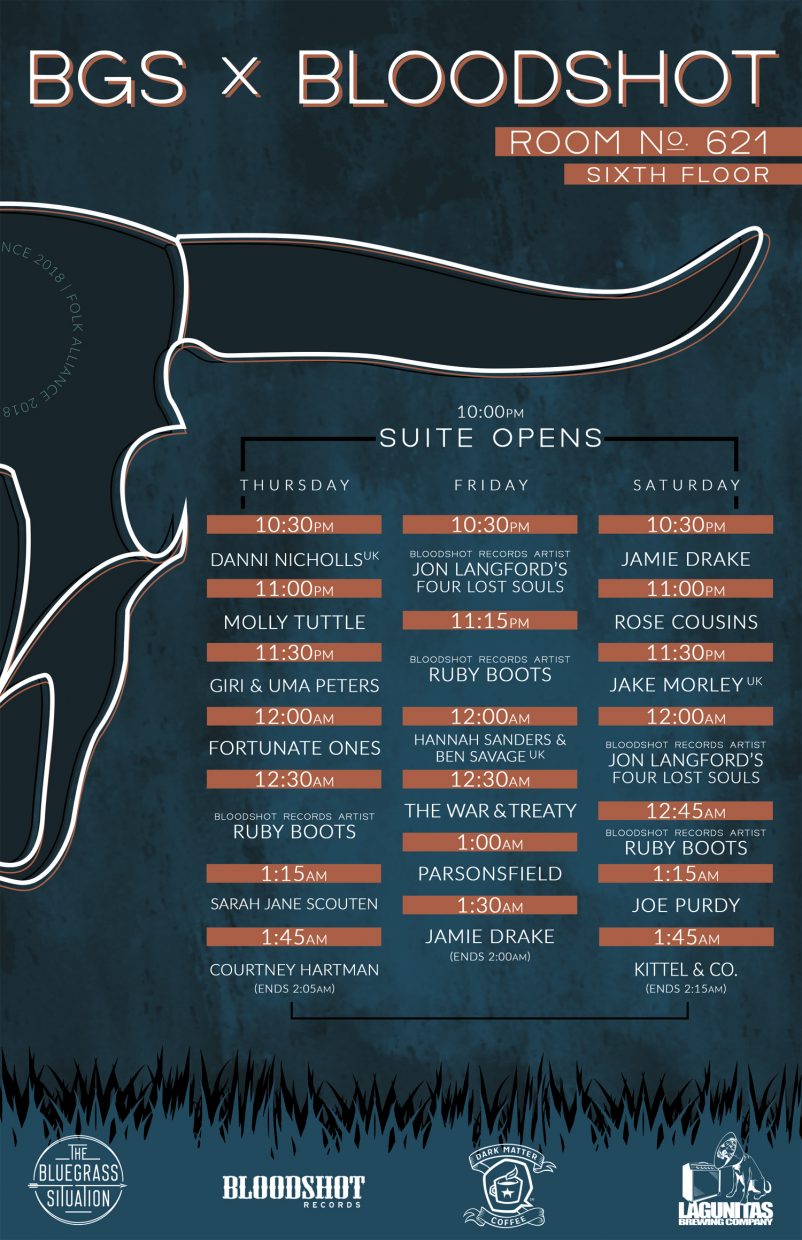

BGS contributor Justin Hiltner strolled down New Orleans’ Canal Street with Lee during Folk Alliance International to find a secluded, sunshine-y balcony for a chat about action, queerness, folk traditions, fatherhood, and much more.

My first experience with the new record was the video for “The Garden of England.” It felt so lush and verdant, it immediately made me think of your relationship with nature and the ecosystems you operate in, as well as your environmental activism. How strong of a presence do you think that part of your life — the activism, especially the environmental aspects — carries through the album? It’s visible in a lot of places overtly, but there’s an undercurrent in there, too.

It’s funny, you use all of the words that I use, “How overt/covert” or “how implicit/explicit it should be.” Since the previous album I’ve gone through a very different journey of who I am, what I am meant to be doing, and why I’m doing music. I’ve come to the acceptance that actually, first and foremost, I’m an activist, not a musician. Music is the medium through which I disseminate, articulate my activism and my beliefs within that.

I’m very thrilled that I can do it in a way that is emotionally guided, as opposed to having to be statistically informed, or having the best persuasive political argument, which I’m terrible at. Through the mediums of song, ancient song, song that’s connected to the land by nature of its ancestry, I found I’ve got these really unusual resources and tools.

Something I like to ask musicians a lot is, how do we make this music relevant? How do we show people it’s not just throwback music or time capsule music? What I heard you describing is that you’ve found a relevance in these old songs for this current moment in geological time, due to the climate crisis, but also socially and politically.

It is that, but I say it’s more about the essence of the songs. … I’m playing with tradition, but there’s a certain distillation process that I’m using within them, which like any distillation process is also highly adulterative and adaptive. I’m contorting them, but I’m also working with an unusual aesthetic, because that’s all we can do, be artists. I’m taking risks.

Like, with videos like [“The Garden of England”] and the one that’s just come out last week for “Lay This Body Down.” I’m going to use mainstream values and imagery and concept on some deeply ancient ideas in a way that doesn’t really happen very much. And I’m not saying that’s because I’m pioneering! [Laughs]

I think it’s a vital thing to have to address, how does one tell these stories in ways that are going to be digestible by a new audience? One that actually would never encounter the tradition, in certain ways, because in the UK we live in a very musically segregated society. Most people aren’t thinking about music or that music can change identity, especially on such an ancient level. I’m having to test these things out.

Roots music and eroticism don’t really feel like they go together. “Lay This Body Down” feels so timeless and ancient, but the video for it has this level of eroticism and sensuality that feels current. I may be projecting my own queerness onto it, but I wanted to ask you how much of that eroticism comes from your queerness, or doesn’t it?

You know, you might be the first person to ask me these questions. Generally music journalists where I come from are uninterested in that, or the ones that are wouldn’t come across me.

I didn’t approach it from a sense of wanting to work with queerness, I love working with dance. I come from a dance background

And dance is very queer as is.

It is, but why does it have to be? Because the irony is, and it shouldn’t make any difference, that all the dancers in that video are heterosexual. That doesn’t matter, but it was so wonderful working with men who were actually very comfortable with their heterosexuality, but also in their intimacy and physicality and their sense of body contact. Working and being in that space was so energizing. It wasn’t erotic, it was simply sensual. The funny thing is it comes across as erotic, as homoerotic, but in all honesty I think that’s the viewer’s perception.

Maybe what I mean by “the video feels queer” or “dance itself is queer” is more accurately, “It leaves the door open for non-normative ideas and feelings.” Is that what you mean? The viewer can sense this because you left a crack open in the door of normativity for people to step through?

You’re absolutely right, and I’m very conscious of that. There’s a very Caravaggio-ness to this film. You couldn’t put any more arrows pointing [toward eroticism and homoeroticism.] I’m also fascinated with the queerness of folk song, particularly in the ambiguity when men are singing from the perspective of women and all those sort of rule-breaking things that were never rules in the first place.

I think it’s only the conservatism, in the sense of boxing what “is” and what “isn’t,” that binary-ness, that starts to do that. When you actually go back into history, those sorts of boundaries [weren’t as present], and I think that’s what I’m celebrating a little bit.

It’s a song about death, actually. These aren’t sexual beings, they’re mortal or immortal or transitionary. Their nakedness is as much about that shedding of materiality of the living and this idea of the trajectory from one realm to the other. They’re all expressions of myself… That’s what these movements are all about, for me.

That sort of ambiguity you mention, “Sweet Sixteen” felt to me like it was pulling from that tradition — am I reading too much into that? Where did that song come from?

Interesting. It’s not [from that], in fact, for me it’s the most heterosexual moment of my entire career, that song. [Laughs]

Interesting! And right, I heard heterosexuality in it, but also — and again, perhaps this is my projection — more than that, too.

This is the funny thing about making music, once you’ve put [the songs] out, you don’t own them anymore. They’re not yours. And never would I ever want to make music that was utterly explicit.

The song was a really hard one to choose to do and I don’t know why I did choose to do it. It’s actually more about me being a parent, because I’ve become a dad. In many ways I’m living in a heteronormative set up, even though it is unusual. We’re not together and we don’t live together and we never have, but the itinerant-ness of being a musician and leaving mum doing most of the care requires a little bit of me acknowledging that, through song.

This is my acceptance that I am a bit of that, packing my bag and heading off, away from the family set up. It also holds a little bit of my judgment upon that nuclear family thing, of husband and wife and child at home, and my terror of that. Which, I think has nothing to do with being gay. I think if I was straight I’d probably feel like that, too. [Laughs] It’s very much me trying to channel what a baby’s mother is thinking.

You carry on this tradition of folk singing unencumbered by music, a capella, but that to me, as someone who is a singer and musician, is kind of terrifying. The space that you play with, as a vocalist, on this record feels so vulnerable. What does it feel like to you?

I think I’m quite comfortable with vulnerability. Which is sort of a paradox, in a way, because the point of vulnerability is that it is uncomfortable. I think that space of exposure, for me, is a very exciting place. It’s not exciting because I get to see myself more, it’s because by being vulnerable you have to step outside the realm of protection, of comfort, of security. In that position you can do much more interesting things, finding perspective and placement and by that, a relationality to the world around you.

[Sometimes] you have to be an outsider, and that’s something that, by nature of who I am — by being gay, by being Jewish, by being the kid that never quite fit into any of the places that I was I’ve always been in that position. It’s a place I’ve always been drawn to, most artists are like that one way or another. I’m not particularly exceptional, I’m not saying I’m necessarily special, but that’s something that I’ve certainly been accustomed to.

When it comes carrying on the tradition, I did exactly the same. I went down the deepest root of folk music, but never went fully into those folk scenes. I was always an outsider in the folk world. I was always an outsider in these deep traditions, I was never part of the communities that I’m learning from. Yet, at the same time, you find yourself weirdly in the center of these places as well. This idea of, there is no center and there is no outside. Actually, these are all constructs only in our minds and we are all outsiders in the end.

When it comes to the music — and it’s funny, because I didn’t mix the album, though I was very involved in it — when [producer] Bernard Butler did that we were very aware of keeping the voice up front and center. Maybe there’s a little bit of ego and selfishness that he’s recognizing. That, as a singer, you need to be center. You are your voice. Not because I want to be up front, but maybe because I’m very clear about what I want to say in this record, so I think I have to mark my place in that respect.

Photo credit: Julio Juan