Bobby Rush is a character, the lines between his true self and his stage act blurring until it’s hard to tell which is which. And perhaps that’s the point. There really can’t be any sharp distinction, because Rush is a performer through and through, his time on stage merely a larger — and sparklier — version of the man he is day to day. Rush isn’t his real name, of course, but from the way he likes to refer to himself in the third person, you’d be hard-pressed to think there was anyone else beneath the folk-funk fiend who sings about being a “Night Gardener” (mowing a different type of lawn, if you catch my drift). Rush was born Emmet Ellis, Jr. in Homer, Louisiana, in 1935, before his parents moved the family to Arkansas when he was 11. As a young adult, Rush continued north, landing in Chicago until Jackson, Mississippi, called his name 48 years later and he resettled there, halfway between his first home and his most formational. “I been in the big city, out the big city, in the country, in the small town, what have you,” Rush says, his words coming in a — wait for it — rush, all peppered with a lilting Southern accent. The styles he picked up along the way all informed his music — a flashy, fun take on funk that’s as innuendo-laden as they come.

The number of songs Rush has recorded isn’t just impressive, it’s staggering. He likens the figure to well over 300 tracks, but add to that his latest effort, Porcupine Meat, and Rush doesn’t just show a proclivity for songwriting, but a fever for it. Porcupine Meat, the kind of strained relationship involving a woman one doesn’t really want but hesitates to set free, marks his debut with Rounder Records. Like the title suggests, it showcases all the sexy jocularity that makes Rush such a popular draw night after night, even as a touring octogenarian. Rush’s funk comes packed full of colorful lyricism and lots of wink-winks, but with new contributions from Dave Alvin, Keb’ Mo’, and Joe Bonamassa on the album, he’s once again made some seriously catchy music for the Saturday night crowds before they make it to church on Sunday morning.

You grew up a pastor’s son, but a lot of your songs don’t seem like they’d fit in church. How is it that you started exploring this funkier, sexier side to life?

Well, that’s what you think. The same people that come to see Bobby Rush on Saturday night are the same people that go to church on Sunday mornings. It’s like that now and it’s always been like that. Where I come from, there’s a praise dance when you leave this land; but when you’re born, there’s a sad time. Most people have a death, you cry; when you born, you smile. It’s kind of the reverse with people from Louisiana. You’re kind of sad when you come here, you're happy when you go away, especially if you go at peace.

You’ve cut so many songs. Where does that drive come from?

I think it comes from being desperate to be someone, to be a superstar. I’m blessed to have this work. I’m just a crazy guy who don’t mind working, who don’t mind putting my hand into the grits. It’s part of my personality. Somebody told me I could make some money doing what I’m doing after about 20 years in the business. It wasn’t about the money, at the beginning; it was about the love of the music. I still have the love of the music, although I still wanna get paid for things. But I love what I’m doing. I love the music. I love the people that I’m doing it for, and the reaction from them still gives me that drum to keep going. It’s like a shot in the arm.

I’ve seen your live shows, especially one viral video — “I Ain’t Studdin Ya” — from a show in Memphis about eight years ago, and you sure love bringing the ladies up on stage. As a man in his 80s, what does it take to stay sexy?

It don’t take much to stay sexy — just think sexy. When you see ladies up on stage with me, it’s not about playing sexy; it’s just playing life. My momma, my sister, my auntie … that’s my life. I just like showing the ladies off because I’m praising them. This what makes me go 'round. Whether you in church or whether you in the bandstand or whether you in an alley or a top of a hill, the love of a woman is what man lives for. And I use it that way, too, to have fun and to get people involved with me on a personal level. They look at the ladies, but then I let the ladies walk away, then I get to tell my story as an artist, and I play my music.

Your lyrics are incredibly playful. Where do you drawn inspiration?

That’s my personality. What I live for is taking care of my children, making love, taking care of the lady of the house, and doing for my kids, and doing for others what you wish to have done to you. And I do it for the ladies. It starts with my mom. I take care of my mom, take care of my sisters, take care of the ladies around me like they part of my sisters. If this is my lady, I’m gonna take care of her in a special way. I’m just showing what I do and what I care about in my life. Ain’t nothing in the world to me is more important than the ladies. Nothing. There’s so many times we, as men, put that on the backburners because we men won’t do — and can’t do — anything without the ladies in our life. What do you work for? You work to take care of the ladies, so you can be took care of sexually and, you know, just have fun.

I feel like your song “Porcupine Meat” could extend to more than just toxic relationships. There are so many times in life when we know better and yet still go after things that aren’t healthy.

I was trying to write a song that relates to me and many other men like myself. You get a relationship that’s not as good as it should be, or ought to be, but then you can’t leave because you’ll find somebody just as bad or worse. Then sometimes you got some things go on that’s real good, and you don’t want that to be shared with no other men. You lose something, if you lose a woman. You know she don’t mean you no good, but you just can’t leave. The best way I can sum that up is that’s porcupine meat: "Too fat to eat and too lean to throw away.”

How do you deal with “porcupine meat”?

All you have to do is face it. “Should I leave this lady or should I leave this man?” "But you know this old man I got, he make love decent, but then he don’t stay home, but he bring all his money, when he do come home. I got another man I could get, but he won’t stay home, but he ain’t got no job." That’s where you stand.

There’s always a tradeoff.

There’s always a tradeoff. That’s porcupine meat.

There’s a performative nature to your songwriting. I heard it come through especially on “I Don’t Want Nobody Hanging Around.”

I don’t want nobody hanging around my house when I’m gone! Not even the milkman. People don’t have milkmen today, but back in the day, the milkman brought the milk to your house. I don’t want the mailman bringing in the mail! [Laughs] Stop it at the post office. I don’t even want the preacher coming by, when you all alone. If he want some chicken, let him get it from somewhere else. I say that because, in the Black church, preachers — most of them — love chicken, and they want ladies to cook chicken, but I don’t want my lady cooking chicken for him so he got no excuse to come by the house. If the lights go off, sit in the dark. [Laughs]

That doesn’t seem like a very nice situation for a woman, though.

If you think of it, the dark can be a nice place. If you understand. When the lights off. [Laughs]

Do you think about how these songs will translate to the stage while you’re writing them? That line in “I Don’t Want Nobody” when you start shouting out “you, you, and especially you” seems like it gives you a great moment onstage to play with.

I will visualize. I know somebody in the audience really like the lady I’m with, someone that I’m close to. I’ll say "I don’t want you, you, you, and especially you."

Right, I can see you pointing to that person.

He knows who that is when I point. He knows he has eyes on this girl.

It all cycles back into your show, and that’s where you really get to shine.

I did it this weekend for the second time onstage. I had 200 records with me and I walked off the stage and, in five minutes, they was gone. People was really into that record. I think it’s going to be one of the biggest records I ever cut. Let me tell you what, God has really blessed me to live this long, cutting records. Here’s what happened: I’m from Louisiana, and it’s the first time I recorded in Louisiana. And every musician except one was native of Louisiana. When it was finished, I had tears in my eyes. God has blessed me to come back home and do this for the first time.

It’s reflected in the music; you can hear a different kind of energy. And then you’ve got a musician like Keb’ Mo’ on it. I mean …

Oh God, what a hoooo. [Laughs] He’s just a lovely guy. All my guests were so wonderful. And it wasn’t about no money with these guys. These guys were in love with me, in love with the music, and they just wanted to play with me. I could never never thank these guys or pay these guys for the attitude they put into this playing.

Lastly, from your vantage point, what kind of advice can you offer up-and-coming artists?

I can tell young people, when it’s an old guy like myself, have a talk and listen and watch. When I was a young man, I listened … but not well enough. I disrespected Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf when I was very young. I took it for granted. These guys loved Bobby Rush, they had their arms around me.

I’m the last of the kind to do what I’m doing. I surely want to pass the torch on to the young guys. You got some older guys still doing it. But mostly an older guy is doing it in an old-fashioned way. What I like, the young guys are doing … they try to do what I do: I’m an old guy, but I still create, and do new licks and new directions and take it to another level. That’s what guys have to do. The Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, BB King … all great, but it’s been done. We got to take their foundation and create something from that and make a new thing.

You always have to be growing and stretching.

We have to modify. We don’t want to modify too much and lose what we have. We don’t want to cross over and cross out.

For more Counsel of Elders, read Amanda's interview with William Bell.

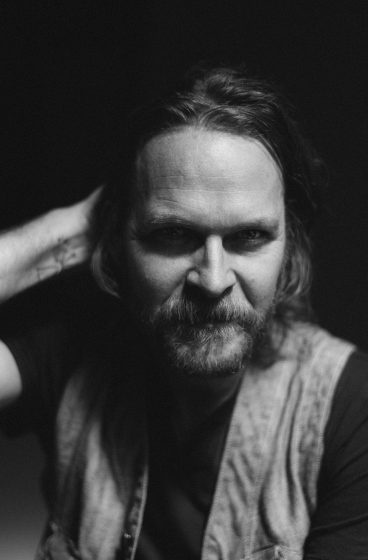

Photo credit: Rick Olivier