Early in my recent interview with Swamp Dogg, the iconoclastic singer-songwriter and producer makes a self-aware confession: “I have read columns about Swamp Dogg and so forth, and I try to find out what they classify me as,” referring to the veritable grab-bag of hyphenated micro genres that music writers use to classify him. We connected a few days out from the release of his latest album, Blackgrass: From West Virginia to 125th St, and the artist, born Jerry Williams Jr., seems unbothered. Later he adds, “When I do the Swamp Dogg albums, I really don’t try to please anybody but myself.”

He has known from the jump that the music industry doesn’t know what to do with him. Working as a singer and songwriter under the name Little Jerry Williams, Swamp enjoyed some success with his 1964 soul 7 inch, “I’m The Lover Man,” and was subsequently invited to perform at clubs in the Midwest. As Swamp remembers, “When I showed up they found out I was Black and the audience was lily white. They were good about it, they paid me and said I didn’t have to do a second show.” The small-mindedness of industry gatekeepers would follow him into his first musical steps as Swamp Dogg.

In 1971, Swamp released his second album, Rat On!, on Elektra Records. He was dropped from the label immediately after the release. At issue was the provocatively titled, “God Bless America For What,” track six on the album, which Elektra had pressured Swamp to leave on the cutting room floor. He kept the song, and his brief stint with Elektra was over. (The album cover, featuring Swamp in a victory pose astride an enormous white rat, might also have earned him some detractors in the office.) Asked if he considered caving to the label’s demands, he quickly sets me straight. “No! No. Nuh-uh. I’m dealing in truth!”

The controversy surrounding Rat On! did nothing to slow Swamp’s momentum as a creative force and in the years since its release, has proven itself a classic of left-of-center soul. He produced artists like Patti LaBelle, Z.Z. Hill, and Irma Thomas. Swamp also continued working in A&R. He signed a still-mostly-unknown John Prine to Atlantic Records in 1968, later reuniting with Prine for what would turn out to be the final recording made by the legendary storyteller. Swamp built a cult following among indie music fans in the know, collaborating with artist-tastemakers Justin Vernon and Jenny Lewis – the latter of whom returns as a guest on Blackgrass, as well. He dunked on the snobbier side of the mainstream with albums like Love, Loss, and Auto-Tune, and I Need A Job… So I Can Buy More Autotune.

A list of Swamp’s credits tells the story of one of the most fascinating music careers of the last century, but he himself tells an even deeper one. He speaks about painful failures, like when he became a millionaire in the 1970s and the sudden reality of wealth gutted his mental health. “The right word is obnoxious, I really became obnoxious, my wife pointed out to me. I was running so much that I would run in my sleep and run out of the bed.”

When the nine cars in the family garage proved insufficiently curative, she got him to see a therapist, a “who’s who psychiatrist” in Swamp’s words. He tells me so many sweet things about the great love of his life, Yvonne Williams. “My wife, she was a Leo. She was a strong Leo, she was a leader. Everybody loved her. Everybody feared her when it came to brain-to-brain. She could knock your shit right out the box. She was the reason I made a little money. Her name was Yvonne and I still think about her.” Subsequent girlfriends have told him he is still in mourning, and a second marriage was short-lived.

Discussing his musical roots, Swamp lists “blues, soul, R&B, pop, just about everything except classical and polka, and gotta add country there, cause country is what I was listening to growing up as a kid.”

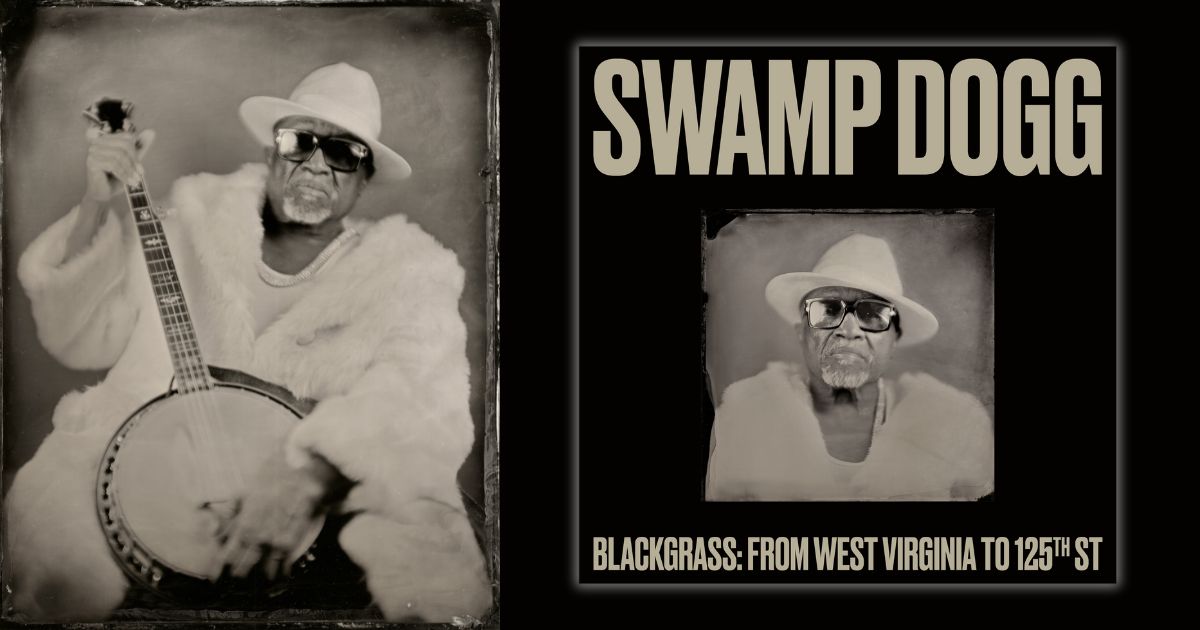

His brand new record, Blackgrass, released May 31 on Oh Boy Records, is an inventive, often moving exploration of the genre. Sensitive instrumentation by Jerry Douglas, Sierra Hull, Chris Scruggs, and Noam Pikelny, among others, pairs beautifully with Swamp’s varied vocal performances across all 12 tracks. “The Other Woman,” featuring Margo Price, is an elegant update of the classic written by Swamp and first performed by Doris Duke. And Swamp himself is at home as a country vocalist, playing characters like the neighborhood ne’er-do-well on “Mess Under That Dress,” the lovelorn crooner on “Gotta Have My Baby Back,” and delivering a breathtaking country gospel performance on “This Is My Dream.”

Even as Blackgrass offers country music moments that should please even the most determined traditionalists, Swamp Dogg remains committed to surprising his listeners. “Rise Up,” for example, a Swamp original first recorded by the Commodores – “Atlantic didn’t know what to do with them!”– is reincarnated as a country-meets-alternative rock and roll foot stomper, with a guitar solo by Living Colour’s Vernon Reid, which readers should listen to in a safe and seated position.

One of the great rebellions of Blackgrass is the singer’s assumption, on an album that is being marketed to country and roots media, of a Black audience. He explains, “I’m calling it Blackgrass … mainly because of the banjo. When I was coming up the minute somebody said ‘country music’ or ‘banjo’ … we turned our nose up at it, way up until Charley Pride came along.”

As Black listeners, we are being made to understand that this record is for us, decades of deliberate exclusion from the genre be damned. Its creator is equanimous about how the art will be received. “If this one sells enough, there will be a next record. If it doesn’t, there will still be a next record. I’ll put it out myself.”

Fifty years since “I’m The Lover Man,” Swamp Dogg remains curious about, and frequently explodes, the boxes into which small-minded gatekeepers of popular music have attempted to place him. As he recalls some of the more colorful antagonists along his musical journey, Swamp is gracious in the knowledge that he has had the last laugh. He speaks with refreshing pettiness about his early critics, reasoning, “The people that I dealt with back in the day are either dead or don’t know who they are. And I know I’m in line for that, but I keep jumping out of line. When I see myself getting near the front of the line I jump out and go to the end of the line.”

As usual, Swamp Dogg plays in his own time. He has finally outlived the haters.

Photo Credit: David McMurry