The other day I was going through my closet doing some spring cleaning, when I found a box with a bunch of old things that just took me back. One thing in particular was my old CD binder that I used to keep in the first car I ever owned, my parents old Ford Windstar. When I started looking through the binder, it brought me right back to the first time I moved away from home. At 19, I decided to leave the city and start working on a vegetable farm as a labourer. I was really into gardening and growing food at the time. Being out there was a time of many firsts, first time moving from home, first love, first time out partying (I’d always been a homebody).

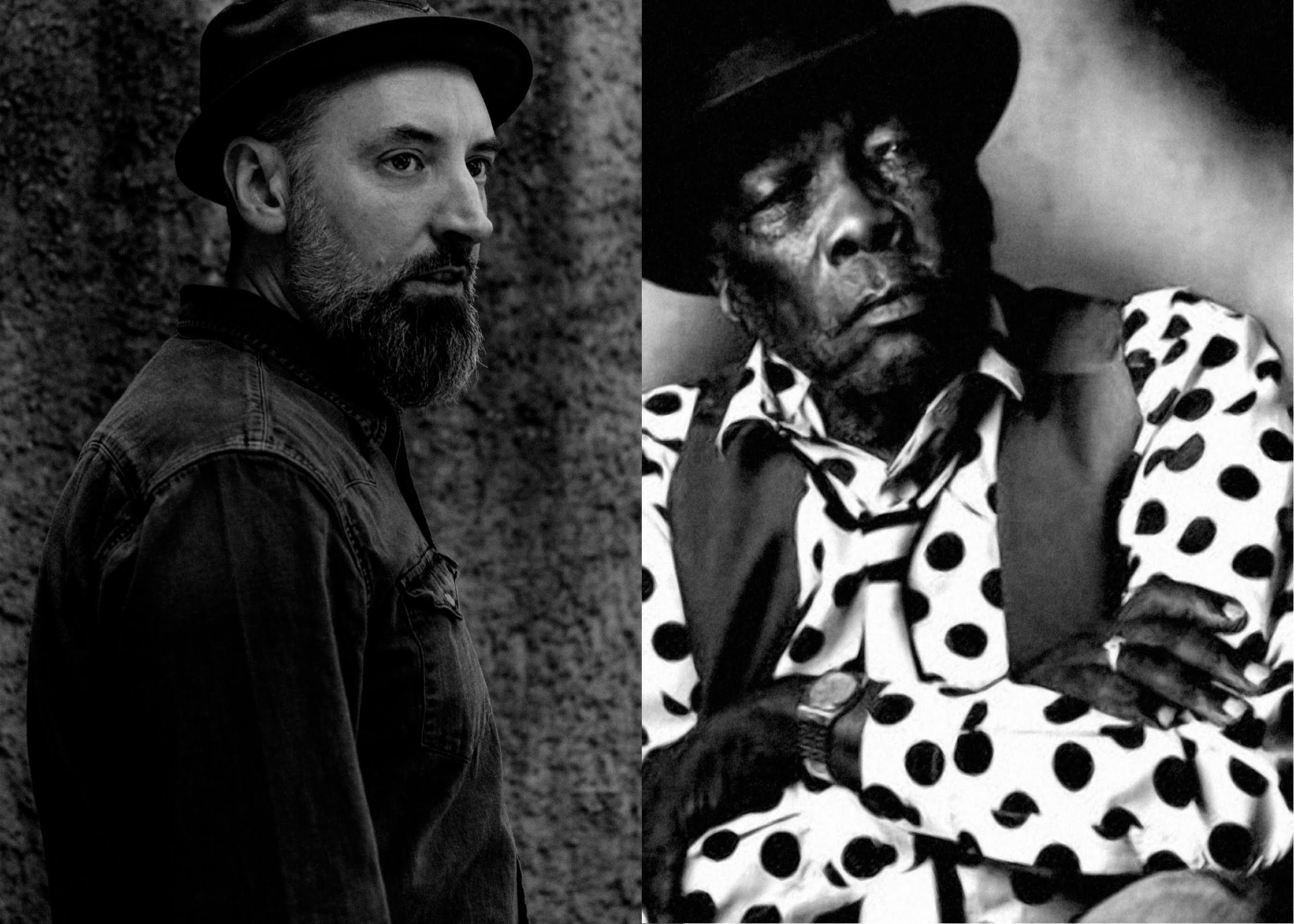

This find made me think of turning them into a digital playlist, “Songs That Take Me Back.” Something that I could take with me, wherever I may go. Here’s a playlist of songs that somehow take me back to a moment in my life, and I’d like to share them with you. – Jeremie Albino

“Trouble” – Ray LaMontagne

This was the first CD in that CD binder that really brought me back. I could just smell the lilacs in the spring time driving out in the country with my old Windstar with the windows down, blasting this record.

“Sylvie” – Harry Belafonte (At Carnegie Hall)

This song brings me right back to an early Sunday morning when I was a kid. I’d be sleeping in and my dad would throw this on his five disc CD player, blaring records while he’d clean the house. This is probably one of my all time favourite records.

“Dust My Blues” – Elmore James

When I hear this tune, it reminds me of the first open mic I ever participated in. I was probably 15 or 16, I had been so in love with this song and had to learn it. I didn’t do too bad, the audience seemed to enjoy a 15 year old trying to play the slide guitar.

“Only Son” – Shakey Graves

This song takes me back to the summer of 2015 — I was so in love with a fellow farmer who worked at a farm not too far from mine. She was so cool, she had the coolest taste in music. One of the first times I had found someone who liked so much of the same music as I did. The song specifically reminds me of that first date, where we had pizza on a dock and listened to Shakey Graves.

“Harriet” – Hey Rosetta

This song reminds me of the first tour I ever went on. I was in a folk trio with my best friends called En Riet. We went on an epic first tour, drove eastern Canada all the way to Newfoundland, one of the most beautiful places I’d ever seen. We would listen to Hey Rosetta driving through some of the most scenic drives I’d experienced in my life, the music felt so fitting and right.

“Hey Boogie” – John Lee Hooker

The first CD I ever purchased was a compilation record called Blues Legend. It was all John Lee Hooker. I got it from the Future Shop (fellow Canadians, do you remember this store? So good.) when I was 7 or 8. I have no idea why I bought it or why I was drawn to it, I think my parents probably told me I liked blues and brought me to the blues section. I ended up picking it cause I thought the cover looked cool! Turns out it was a good pick and listening to it now, it brings me back to being a kid.

“Shipwreck” – Jeremie Albino

This is the first song I ever wrote. I wrote this one 10 years ago; it’s always nice to look back to see how things started for me. At the time I was having such a hard time writing music, and on weekends I would meet up with some friends and have a kitchen jam session. We’d go in a circle, sharing songs. My friends would always share a new song they’d been working on, and I would just play covers, since I still hadn’t written a full song. After coming home from one of these sessions, I told myself, “That’s it! I’m writing a song.” So I thought about how much of a hard time I was having writing and the line “I’m a wreck” came to me cause that’s what I was feeling when I was writing. Eventually one thing led to another, and I started thinking about what other things are wrecks and long story short, “Shipwreck” was born.

“Stumblin’” – Jackson & the Janks

“Stumblin’” was a song that was a must-listen when I was on tour with Cat Clyde. I remember the Mashed Potato records compilations had just come out and I started listening to these songs non-stop. With “Stumblin’” in particular, I just couldn’t get over how good it was! I had sent over the album to Cat so she could listen to how good it was, too! So by the time we hit the road together, we probably listened to that song a million times combined, no word of a lie.

“Boxcar” – Shovels & Rope

I remember the first time I heard this song was one of the first times I went to a bar and partied with friends. A local band was covering the song. When I finally got my hands on the record I fell in love with their music, the songwriting and vocals. I had a huge crush on Cary Ann’s voice. After that Shovels & Rope turned out to be one of my favourite bands. Ten years later, we actually ended up hitting the road together for a tour and it was one of my “I made it” moments. I feel very blessed to call them my friends, it’s funny to see how things come full circle sometimes.

Photo Credit: Colin Medley