This week in Kansas City, Folk Alliance International beckons to those people who love intimate songwriting, intentional activism, and interesting interactions at every turn. The Bluegrass Situation will be on the ground with hundreds of other music fans and performers, seeking out new talent and engaging with the legends. Here are some of the moments we’re most looking forward to.

First-Timers Orientation

Wednesday, February 1 at 3 pm

Pretty much everything related to this conference–from the trade show to the showcases–takes place inside the Westin Hotel, so you’ll find yourself squishing into elevators with the same faces throughout the five-day event. The inevitable question is, “What are you going to see next?” That’s up to you, of course, but this mixer will help you make a game plan to maximize your time at Folk Alliance. Sure, it can be intimidating at first. But once you get used to it, it’s also one of the most welcoming events in the music industry.

International Folk Music Awards

Wednesday, February 1 at 8 pm

One of the most popular gatherings of the week, the International Folk Music Awards recognize the achievements of the past year as well as the accomplishments of the genre’s icons. Leyla McCalla and the Milk Carton Kids are among the confirmed performers. Take a look at the nominees and special award recipients and enjoy an evening of wonderful speeches and song.

Black American Music Summit

Wednesday, February 1 at 4 pm

Thursday, February 2 at 11:30 am

Friday, February 3 at 12 pm

Saturday, February 4 at 12 pm

Black artists and industry members will confer about ways to empower one another with daily conversations during this four-day summit. The first session on Wednesday is subtitled “Setting the Tone,” while Thursday tackles the theme of “It Takes a Village,” which helps leaders learn how to lean on others to grow their business. On Friday, the topic is “Money Matters,” with tips on identifying revenue streams and best practices for touring, applicable to artists and industry alike. The final installment on Saturday explores the vast and ever-changing modern landscape of Black Music with a two-hour program subtitled “Lifting the Gaze.”

Valerie June Keynote Address and Artist in Residence

Thursday, February 2 at 1:30 pm

Tennessee native Valerie June is one of the most versatile figures in roots music, with her creative output ranging from Grammy-nominated albums to a new children’s book. Her afternoon keynote address is likely to touch on some of her favorite themes, such as finding joy, mindfulness, and communing with Mother Nature. Prior to her appearance, the conference will host a presentation from its Artist in Residence. Cary Morin will speak about his experiences with Friends of the Kaw, a grassroots organization dedicated to protecting the Kaw River (also known as the Kansas River). He will also sing a song written about the experience.

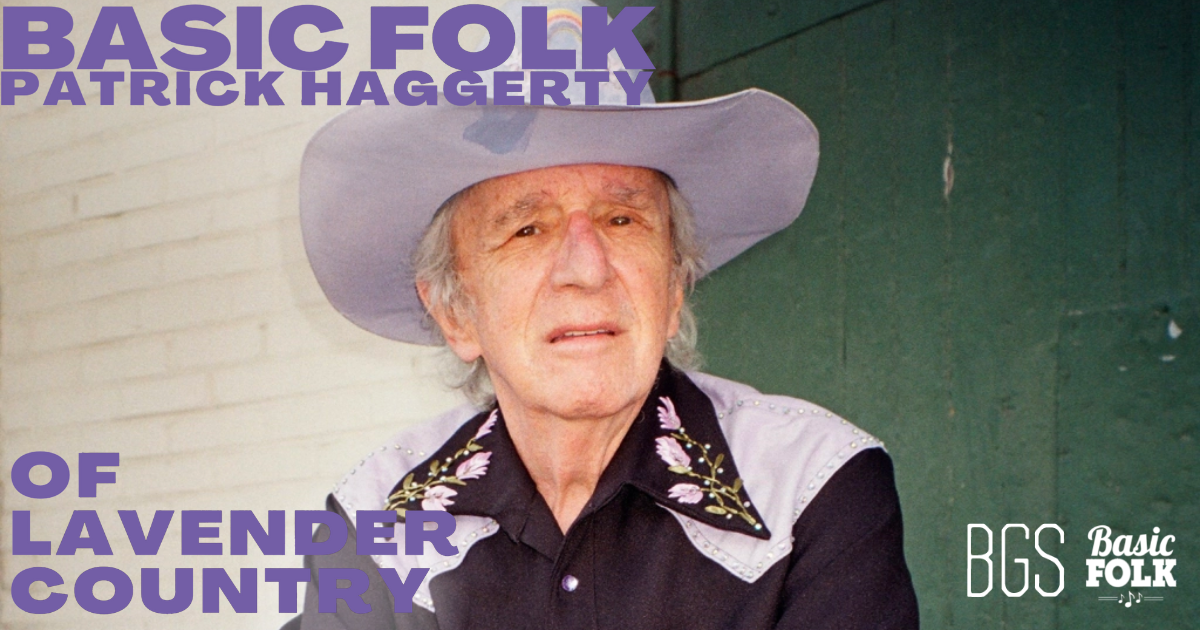

The Queer Pulse of Society: A Conversation About Community and Social Sustainability

Friday, February 3 at 10 am

This conversation presented by Bluegrass Pride will offer insight from performers and industry professionals about their interactions in the music community. Topics include intersectionality, identity politics, and socially sustainable models of business. The discussion will be led by Lillian Werbin (president and co-owner of Elderly Instruments), Marcy Marxer (a prolific recording artist in children’s music), and Sara Gougeon (founder of Queerfest and part of the FAI social media and marketing team).

Mary Gauthier: Saved by a Song

Friday, February 3 at 2 pm

Mary Gauthier shared her highs and lows of her path in her thought-provoking memoir, Saved by a Song: The Art and Healing Power of Songwriting. In this special interview session at Folk Alliance, she will describe how songwriting can bring people together, even when it seems that they have nothing in common. If you’re looking for wisdom and insight from one of our most masterful artists, don’t miss this one. The interview will be conducted by folk radio personality Marilyn Rea Breyer.

CommUNITY Gathering: Meet the Team

Saturday, February 4 at 9:30 am

It should be clear by now that Folk Alliance has an approachable vibe. That extends all the way to the organization’s leadership. All delegates at the conference are invited to this gathering that features new executive director Neeta Ragoowansi and new board president Ashley Shabanakareh. After a few remarks, there’s a casual meet-and-greet. BGS executive director Amy Reitnouer Jacobs will also be on hand, alongside Folk Alliance deputy director Jennifer Roe. Yes, we know it’s early, but there’s coffee!

Janis Ian: In Her Own Words

Saturday, February 4 at 10:45 am

The enduring singer-songwriter known for “Society’s Child” and “At Seventeen” is now in the twilight of her career. An unusual case of laryngitis forced her to cancel her farewell tour but it hasn’t dimmed her status in the folk community. She’s revered for her way with words and her honesty, not to mention six decades on stages around the world. Her final album, The Light at the End of the Line, is a proper coda to her recording career but you can expect this informal chat to survey her full career. Stick around for a Q&A after the talk.

Songs of Hope, Songs of Change

Sunday, February 5 at 10 am

By now, you’ve made new friends, discovered amazing artists, and stayed up waaay later than usual. Congrats! Close out the event with this grassroots multi-artist concert featuring songs written about climate and social justice written by FAI artists. Hosted by the People’s Music Network, the event is intended to rally the activist in all of us. As the (highly recommended) Folk Alliance 2023 app says, “Come lend your ear and lift your voice at this Sunday morning event, as our community collectively and creatively engages with messaging and meaning that will inspire us all.”