By the time Sean and Sara Watkins were about to launch a new Watkins Family Hour album and national tour, the live music industry (and life in general) got turned upside down by the sudden need for social distancing and sheltering at home. It could have been a major blow for the band, considering that they have built the WFH brand through live, multi-artist performances at the Los Angeles club Largo.

Nevertheless, the siblings are used to making decisions on the fly, so they put their heads together and figured out how to keep the spirit of their famous Watkins Family Hour shows intact. The result? Work From Home, a livestream series on Zoom every Thursday in May that begins at 4 pm PT. (However, your ticket purchases allows you to watch whenever it’s convenient for you.)

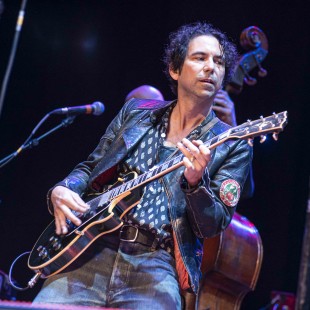

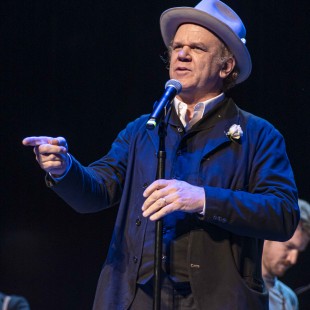

A portion of all ticket sales benefit MusiCares’ COVID-19 Relief Fund. Artists such as John C. Reilly, Mandy Moore & Taylor Goldsmith, Ruston Kelly, The War & Treaty, Mandolin Orange, Mike Viola and Tré Burt have all confirmed appearances for the series.

During an afternoon phone call, Sean and Sara shared the silver lining of virtually introducing their new album, titled brother sister, to the world, and the satisfaction that comes with launching a successful livestream.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CALW2u_heFt/

BGS: What kind of vibe did you want to capture in this Work From Home series?

Sara: We wanted to try and give people the sense of some kind of normalcy. Maybe if people are sitting at home in front of their TVs or their computers watching it, maybe they can for a second forget that they’re not able to go to shows and enjoy some of the genuine back-and-forth that would happen at a normal Family Hour show. It’s been really nice so far having these moments on screen to catch up with our friends and just connect, in a way, because a big part for everyone’s isolation is that feeling of disconnect.

It’s been surprising to both Sean and me how good it feels to do these shows. We’re putting a lot of thought into the shows and learning how to do them on the tech side. They’re live, so there’s a little bit of a countdown. It’s been a nice, familiar rhythm of, “OK, we’ve got to get ready! We’ve got 15 minutes!” Getting everything ready and making sure we have all the things we need — the set list, any notes we have to ask the guests, and then it starts! And we’re live!

That’s a huge part of our life when we’re working, and then afterwards, it’s a release. And it feels good to play these songs. So, on a selfish level, it’s so nice to have that familiar rhythm. The greater hope is that we’re able to share the genuine camaraderie that we have with other musicians and with each other, and to commune in these very strange times, and to hopefully give company to everyone else who’s in their own isolation.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CAD8eyHh7VP/

The banter makes the viewer feel like they’re part of the conversation, too.

Sara: Yeah! That’s what we hoped for. In the first week, we were able to ask for requests and do one of them, and that’s nice. But instead of chatting with people on this particular series, we’ve just been trying to play a show.

Sean: One thing that we always aim to do at Family Hour is to bring an element of what goes on backstage onto the stage. And a big part of what goes on backstage is conversations about music and life. There’s a tendency to have this onstage personality, or way of talking about things, and an offstage version. I think we’re trying to blend those two. There’s good stuff that gets talked about backstage. A lot of it can be boring for most people but a lot of it can be really interesting.

Sara: The thing about Family Hour is that every show is different, and typically there are a lot of guests coming on and off stage, so there’s not really room for a script, or even a rhythm. So, that has taught us that we need to be prepared and nimble, and to be professional, but in a way that feels natural and honest with the relationships we have with the musicians on stage. This is something that we really care about — these conversations — and we don’t want to fake moments on stage with our guests. We want to have genuine interaction. And a lot of audience members want to see what we genuinely care about, and talk with our friends about.

What has been the reward for you in seeing this Work From Home livestream come together?

Sean: Just being able to do a show for people and see that they’re listening, and hear back from them. A lot of the comments are from people saying where they’re listening from. Typically when we do our shows, it’s just LA people that are coming to Largo, so that’s really a cool aspect of doing these online. We did a fair amount of work and preparation for these shows, and when they go off, especially with technology in play, it feels really good to get to the end of it and to have done it! We’ve done two of them and it felt really good. It felt like walking off stage, kinda. [Laughs]

Sara: We’re learning new things about mediums every week and ways that we can make it look better and sound better. Sean is always trying to up the sonic level, but it sounds really good and it’s nice to be able to have a reason to practice different things, learn different things. The cyclical rhythm is really pleasing and I love that people are building us into their week. It seems like people either have all the time in the world, or no time at all, during this, and it takes an effort to carve out an hour in your day, so I really love that and appreciate that.

Photo credit: Jacob Boll