As purveyors of genre crossing, we like to recognize standouts within a genre that innovated simply by epitomizing a sound with particular skill: tracks that demonstrated what virtuosity could do within a genre, that pushed the genre to new heights (or at least new places) for us, tracks that maybe we used to judge what came afterward. We could list a lot of classics, but this list is really about the tracks that were the standard setters for each of us personally, making a mark in how we thought about a genre or sound. For our Mixtape, we selected a few songs and described the impact the tracks made. — Gangstagrass

Flatt & Scruggs – “Foggy Mountain Special”

Earl’s fast, regular picking in songs like “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” made his three-finger rolls, like the Foggy Mountain roll, iconic. But this heavily-swung tune, while not a slow song by any standard, really explores the bluesy side of bluegrass banjo. The syncopated banjo kick, with the band entering on the second beat, throws off the listener’s perception of time. The main lick itself deserves to be as iconic as any fast-flowing Scruggs roll. And that solo! From the single-string bends to that chromatic octave line, Earl knows to keep playing it just a little bit longer. You couldn’t go back and redo any part of this any better, not in a hundred years. They nailed it.

Norman Blake and Tony Rice – “Little Beggarman/Gilderoy”

Tony Rice sounds his best on duo albums, whether it’s with country superstar Ricky Skaggs on a journey to reconnect with his bluegrass roots, or songster Norman Blake, whose clear-as-a-stream picking and earnest vocals are augmented by Tony’s unparalleled rhythm work and rich baritone. On this instrumental track, guitar and mandolin trade breaks and, unusually, trade tunes. Because they’re both in A, with similar chords and melodies, you almost don’t notice the transition, except that the tune Blake plays on mandolin is minor, while Tony’s guitar tune is major. It’s a beautiful, subtle effect that showcases both artists and enhances the sound of each instrument.

The Steeldrivers – “Ghosts of Mississippi”

Before Chris Stapleton was Chris Stapleton, he was in a band called the Steeldrivers. The mainstream music audience has rightly picked up on his powerful vocals and formidable songwriting, but arguably his best work has been with this band that gave him a perfect setting. From the smoldering growl of the banjo to the searing whine of the fiddle, the sound has not been surpassed by either Stapleton’s pop work or by any other bluesy bluegrass band. This track in particular sets the bar, serving up equal parts groove, emotion, and one hell of a catchy melody.

Béla Fleck and the Flecktones – “Hole in the Wall”

The Flecktones represent Béla’s furthest ventures outside traditional bluegrass, and this late track on their second album, Flight of the Cosmic Hippo, is a representative example of their early sound. Of note, Howard Levy’s keys get more room than on most other tracks which tended to feature more of his admittedly superlative harmonica work. Near the end, there’s enough sonic buildup to justify a fantastic extended banjo solo with fluidly shifting time signatures and tonalities. Banjo players who have tried to emulate this piece will have noticed that, like many Béla tunes, it centers around a particular lick, in a particular nonstandard key, played in open G tuning. But as with magic, sometimes understanding the trick doesn’t make it any less exciting to see it performed right in front of you. — Gangstagrass

Pharoahe Monch feat. Black Thought – “Rapid Eye Movement”

Every now and then there’s a collaboration that you just know is going to be dope just by the parties involved. “That’s what I figured when I saw these two MCs on a track from Pharoahe Monch’s 2014 album P.T.S.D. I wasn’t prepared for HOW DOPE, however,” says R-SON. Pharoahe Monch drops bars about being in a relationship with his ammunition and then filing for divorce and releasing his “ex-calibers.” Not to be outdone, Black Thought starts his verse with the last two lines of Pharoahe’s and goes on to “send shots to ancient Greece to pop Socrates.” Black Thought’s line “the ex-slave sado-masochist/who gave massa my ass to kiss” is, as R-SON puts it, “just another example of Black Thought’s conscious swagger that laces every verse that he blesses a track with.”

Black Star – “Thieves in the Night”

Mos Def and Talib Kweli came together on the Black Star album and created gems but this was the standard for R-SON. Their distinct flows built two very different parts — Kweli’s recounting what his man Louis said and thought and how those thoughts affected Kweli. Mos Def’s verse, on the other hand, had a breakdown of the hook where he responded to the things said in it. The song ends with one of the great lines in the genre’s history: “I give a damn if any fan recall my legacy, I’m tryina live life in the sight of God’s memory.” R-SON notes that “in my younger days the song brought tears to my eyes and I’m happy to say that it still does.”

Mos Def – “Mathematics”

We cannot think of another time when someone counting from 1 to 10 (Dolio the Sleuth on “Ain’t No Stopping” aside) has had more meaning. Mos raps, “5 dimensions, 6 senses, 7 firmaments of heaven and hell, 8 million stories to tell, 9 planets keep orbit around the probable 10th, the universe expands length….” He continues his “…numbers game, but shit don’t add up somehow,” speaking of the number of bars he has to do what he does, and the minimal amount of money he gets from it all. “6 million ways to die for the 7 deadly thrills / 8-year-olds getting found with 9 mils / it’s 10 p.m., where your seed, he’s on the hill/….pumping crills to keep they bellies filled.” His word (and number) play is immaculate.

UGK – “Int’l Players Anthem (I Choose You)”

A seminal “posse cut” that unites two legendary duos of Southern hip-hop, UGK and Outkast, exhibiting four distinct flows and approaches to the subject of being a “player.” Each emcee delivers a memorable verse complete with the stunning street poetry they’re known for, with cadences that ride the beat (or the lack of beat, in the case of Andre 3000’s intro verse) that samples heavily from Willie Hutch’s “I Choose You” from the soundtrack of 1970s Blaxploitation flick, The Mack.

Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys – “Nobody’s Love Is Like Mine”

Rench was listening to 1970s-era Clinch Mountain Boys when he started putting Gangstagrass together as a sound. There’s been a good deal of attention to the Stanley Brothers, but the sound was developed and refined to a new level with the addition of Ricky Skaggs and Keith Whitley. The vocal harmonies are tight and the full string section is on point in a way that epitomizes the best of classic bluegrass sound.

Stuff Smith – “Serenade for a Wealthy Widow”

Stuff Smith is one of the few truly iconic jazz fiddlers. His style is on Charlie Parker’s level. “In an alternate reality, where we weren’t so hung up on jazz’s horn players, I feel Stuff would have been one of the fathers of bebop,” says Brian. Stuff’s style pulls from such a diverse array of influences, from Stéphane Grappelli to the Western swing fiddlers like Bob Wills. The gruffness of his tone and clarity of his lines point to the meld between the character of string band/blues fiddlers players before him like Clifford Hayes and Robert Roberson, and the progressive harmonies that took over jazz after bebop. Stuff is the perfect example of harmonic personality over the harmonic intellectualism that followed. “This track is one of the more off-beat compositions that I love to surprise folks with,” Brian adds.

Slam Stewart – “Oh Me, Oh My, Oh Gosh”

“I feel much the same way about Slam as I feel of Stuff; his musical voice is synergistic of the eras before and after him,” Brian says. The way he rides the rhythm comes from an era of bassists mimicking the sound of tubas in marching bands, indicative of players like Bill Johnson, Wellman Braud, and Pops Foster. His style foreshadows others like Jimmy Blanton, Oscar Pettiford, and Ray Brown with their strong solo personalities. This tune is a favorite; it’s a slick lyric and showcases what Slam can do on all fronts.

Outkast – “Rosa Parks”

This one came out of left field in 1998 — when Southern rap was growing into national attention — and planted a flag with the trademark quirkiness of Outkast style, including a harmonica breakdown in the middle of the song. Their fast-flow style is undeniable and surgical here, while their unabashed Southern drawls in this radio hit opened the floodgates for Southern hip-hop to start dominating the charts.

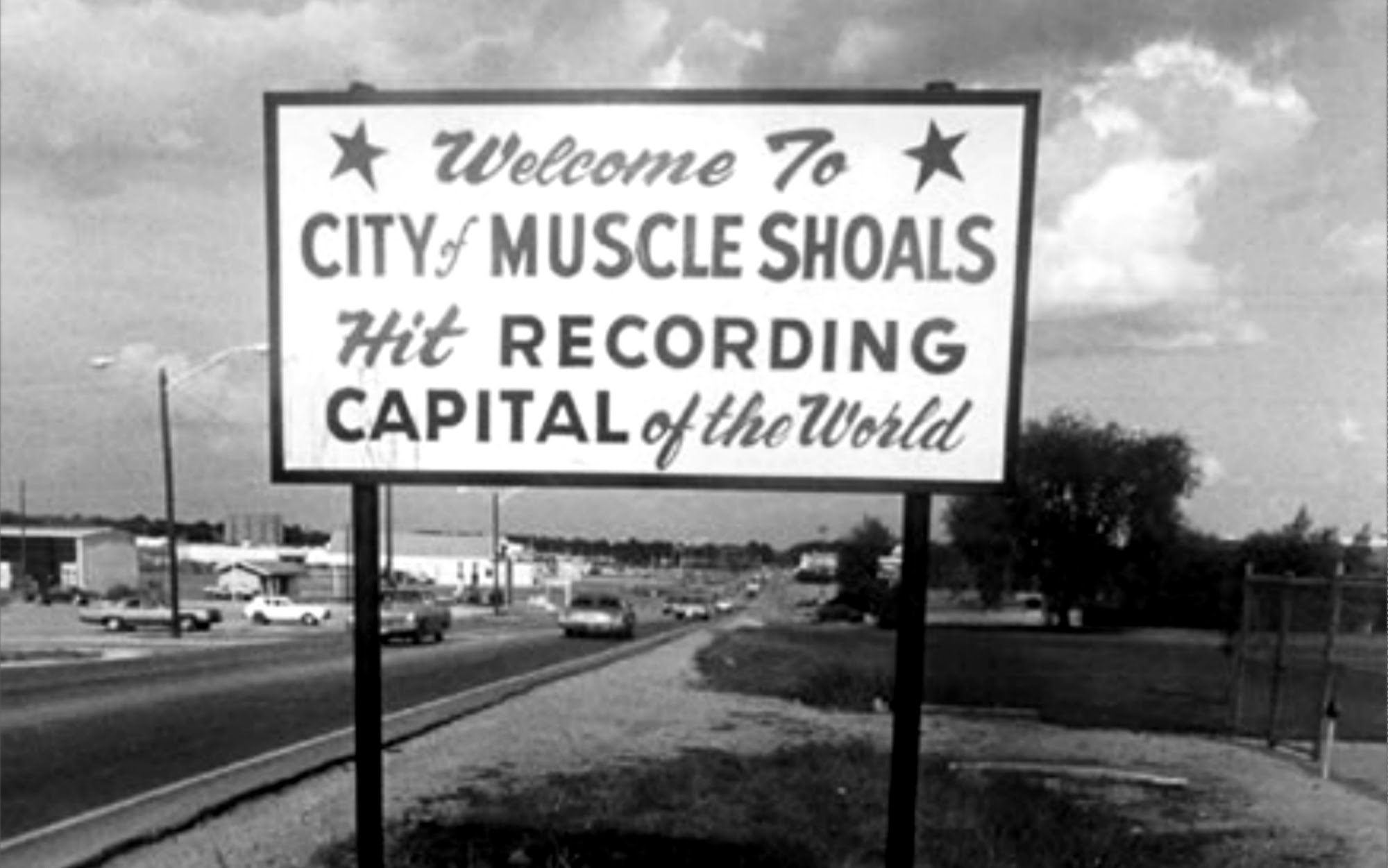

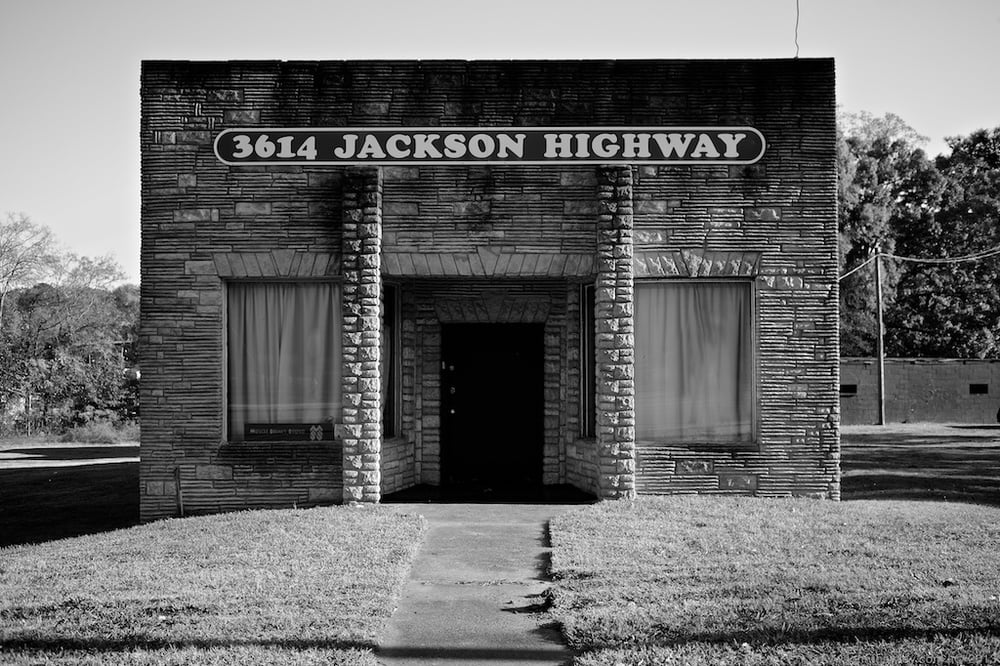

Wilson Pickett – “Hey Jude”

This has a lot to do with the way the Swampers in Muscle Shoals epitomized the soul sound of the ‘60s in the best way, but this track in particular pushed boundaries by including what would later become familiar Southern rock sounds, courtesy of a young Duane Allman. Of course, the wicked Mr. Pickett kills it with a prime example of soul vocals just owning the track.

Photo credit: Sean Aikins