“We called it the Holler because we live out in the country in the woods,” says Lari White of her home studio, located just outside of Nashville. “Our house is tucked back in the Tennessee hills, in this real Loretta Lynn holler. We thought it was funny to have this very high-tech studio and call it the Holler.”

White has made a lot of music at this remote studio, both as a recording artist and as a producer. There is always a bustle of activity there, whether she’s writing songs with her husband (Chuck Cannon), tracking sessions in the studio, or running overdubs. Recently, she manned the boards for Shawn Mullins’ latest album, My Stupid Heart, and for Old Friends, New Loves, a double-EP of covers and originals that marks her return after a 10-year hiatus.

White is one of the most eclectic producers in — or just outside of — Nashville today, but she’s also one of the most ground-breaking. After establishing herself as a recording artist in the late 1980s and 1990s, she took on more and more producing gigs, including Billy Dean’s 2005 breakthrough, Let Them Be Little. When she helmed Toby Keith’s 2006 album, White Trash with Money (arguably the best entry in his sprawling catalog), she became the first woman to produce a platinum-selling album by a male country star.

Producing, however, is only one creative outlet among many for White. In addition to her six solo albums and a greatest hits compilation, she also appears in movies (Cast Away, Country Strong) and on Broadway (Ring of Fire, featuring the songs of Johnny Cash). But recently she finds herself drawn more and more to the Holler, where she is currently working with two up-and-coming acts: the Fairground Saints and Julia Cole, a young singer/songwriter from Houston.

“Right now we’re in the sweet spot, because there’s not a record label involved in other of those projects. So there is this blissful freedom of just being in the creative playground, where you write and record for the joy and the challenge of it.”

You started out as a performing artist. How did you make the transition into producing?

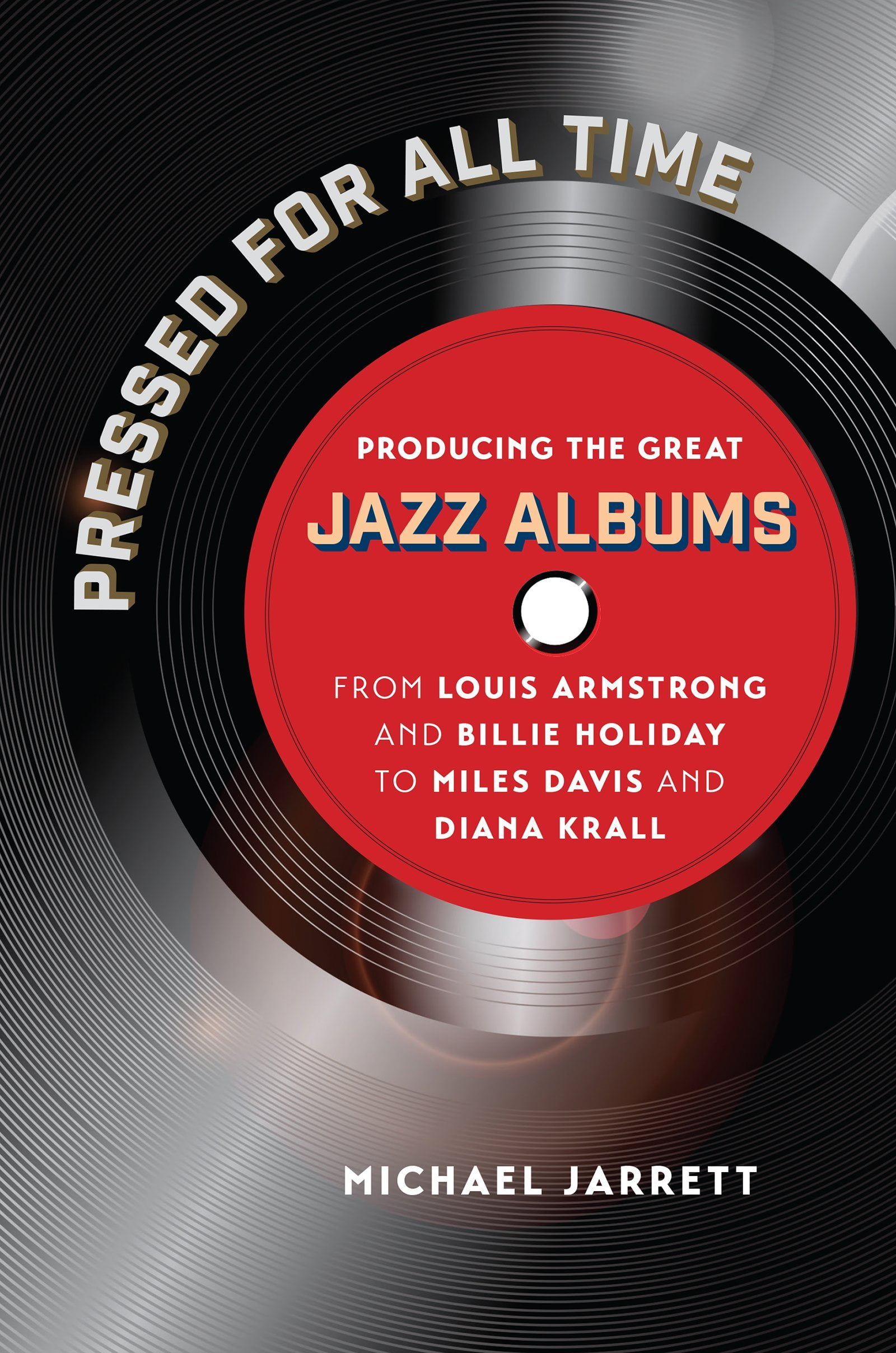

It really started as a kid, as a music fan. I just loved records. I loved the experience of music, and I loved making music. I loved live music. Really, I became a lover of music because of recorded music, the records that my parents had in our house. I was fascinated with playing records, back in the vinyl days. I would sit next to our turntable and just play records over and over and over. Even as a kid, I loved not just the song experience, but the record experience — how the guitars sounded, what kind of space the vocals were in, the sounds they created on Dark Side of the Moon, the soundscape, the whole environment of it.

I’ve always been fascinated by records, but I didn’t really understand that, as a gig, until I went to college and got into the music engineering school. I knew I wanted to be a recording artist and, when I got to the University of Miami, I discovered a whole new program that I’d never heard of before. The music engineering students got to have the studio in the school from midnight until 8 am. There were many, many all-nighters pulled while we were recording somebody’s new song. It was a great experience, and it made me realize: This is how you do it. This is the equipment that you use to get those sounds. This is the kind of microphone that you use to get this kind of sound. This is the kind of microphone you use to get this totally different sound. That’s when I thought, "I’m going to be a producer."

So that pursuit went hand-in-hand with becoming a performing artist.

Pretty much everything I’ve ever done in my life has been to support my performing habit. I looked for anything that would help me get up on stage in front of an audience and make music. That’s why I started writing songs — so I would have material that I could get up on stage and sing. It’s all about performing and sharing that experience with an audience. So I would have to say my first love is the stage. That’s just my happy place. I’ve really grown to love the experience of making records and being in the studio. It’s a very different animal, especially having a studio of my own and having the luxury of being able to be home, raise a family, have a somewhat normal life, and make music. That’s as good as it gets.

Does having a home studio allow you to have a routine as far as working and making music?

There really isn’t so much of a routine, except to make something every day. To sustain a creative life over the years and decades, you get to where you try to make it happen any whichaway. Starting with a song or with a groove, or a piece of poetry — however you can spark it. So I don’t know if there’s a routine, except just trying to listen to a song and get a feel for what it wants to be. It always starts with a song, either one we’ve written or one another artist brings in. Every song has its bones, and the bones might be a programmed drum loop or a guitar riff or some melodic signature. There can be a lot of information in there: Is it a rhythm section kind of record? Or is it a layered wall of sound? Does it need thick, dense textures? We try to figure out what it wants to be.

I’ve read some stuff about Michelangelo, who believed there would be a sculpture inside a rock. The sculpture already existed inside the rock, and he was just taking away what didn’t belong in the sculpture, getting rid of the extraneous material. It’s a little bit like that with a song. It feels like there’s a lot of inherent information in the song itself, and you have to get rid of everything that doesn’t belong.

So you’re not coming into the studio with a finished song. It sounds like you’re doing a lot of exploration in the studio, a lot of trial and error.

Until recently, most of my work in the studio has started with a complete song, but that’s just because I’m coming out of the Nashville songwriting community, where you have to be able to sit and play a song with just a guitar or just a piano. That’s how you test the song and know if it’s alive, if it can live on its own, just stripped down to the bare bones like that. Most of my production has been in that context, where we go in with finished songs.

But recently, I’ve been more into writing loops or creating instrumental environments that we can flesh out into a melody or a lyric. I’ve been writing with a couple of different artists, and the writing and recording process has been much more integrated. The track informs the writing of the song, and the song informs the development of the track. I’ve read about how Fleetwood Mac and a lot of rock bands will go into the studio with no complete songs, and they’ll generate songs and a complete record. That sounds like a really exciting way to work, and I’m getting a taste of that right now.

How do you balance the aesthetic demands of writing a song and the technical demands of working in the studio? Are you trying to keep them compartmentalized?

Like a left-brain/right-brain kind of thing? I can say this: I personally do not engineer my own tracking dates. If I’m producing a session with a studio full of musicians, I hire an engineer because I don’t want to be thinking about microphone placement on the kick drum. I want to be listening and responding to the sounds and to the emotional experience. So maybe that’s a partial answer. I hate to say "compartmentalize" because it’s never that neat. It’s more of an emphasis. On a tracking date, my emphasis is on the overall picture of how everything sounds together, how it feels — the emotional environment that the musicians are experiencing and the music is creating. I’m not ignoring the technical. It’s just a question of emphasis.

I really like engineering overdubs, where I can work really closely one-on-one with a musician to get a particular sound to drop into a track. I love cutting vocals and engineering vocals, because I work well with singers. I know how critical it is to hear your voice coming back at you, how important that can be to how you perform, how you use your instrument as a singer. It’s easier for me to integrate the technical into the musical in those situations, where it’s just one singer or one musician overdubbing. But I don’t like to be thinking of technical stuff at all, really. Unless it’s like, "We’re not getting the right sound, so let’s try another microphone."

You definitely seem to have a facility with singers. Something that struck me about Shawn Mullins’ new record, as well as Toby Keith’s White Trash with Money, is how you put their vocals in all these different settings, yet you allow them to move very fluidly from one style to the next.

I think I’m hyper-sensitive to that, being a singer who has had great experiences in the studio and some really miserable experiences, as well. When you’re giving a vocal performance that’s going to be captured forever and that’s going to define your identity as an artist, it can be really high pressure. So it’s important for me to create an environment where the singer feels comfortable and excited and energized and free to experiment and be spontaneous, yet safe to find their outer limits. That’s a big part of my process — making sure the vocalist feels good and empowered.

How do you do that?

I can’t tell you. It’s a trade secret.

I honestly don’t know. You just feel your way. It’s a very personal process with each singer. I don’t do a lot of passes. I never make somebody sing something more than a handful of times. Sing it just enough to warm up, make sure their instrument is ready to use, then sing a few passes. Then comp it up and let them listen to it, let them take it away and live with it for a day or two, so they can listen and make decisions about what they want to accomplish, so that next time they come in, they can still execute those choices with a sense of spontaneity.

Also, I have a kickass vocal chain. I have a serious M49 microphone that Bill Bradley did some beautiful work on, and I’ve got a lovely vintage tube tech compressor. I’ve got a hard pre-amp that is so transparent and so robust. I’ve had some great results with that vocal chain. That’s a big part of it — creating a sound that sounds like the singer. There isn’t anything in the chain that is coloring or noticeably filtering or altering the quality of the singer’s instrument, so that when they hear themselves back in the headphones, they feel like themselves. They feel natural and honest. That’s a technical part, but it’s a tender thing.

You just produced and released a double EP under your own name. How is producing yourself different from producing another artist?

It doesn’t feel different, except that I know my personal goals. As a producer working with other artists, I’m always making sure they’re happy and feel like this is the record they want to make, this is the sound they want to put out there. When I’m doing it for myself, I know whether I’ve nailed it or not. But it’s a pretty similar process, a similar mission, to ring some internal bell. You work on it and mold it and play with it until you’re ringing that bell.

Recording artists are always asked about their influences, but I’m more curious about producers’ influences. Who has been a guide or an inspiration for you in this particular field?

I’ve worked with some great producers, starting with Rodney Crowell. I owe him a great debt of gratitude for opening that door professionally to me as a young artist and as a young woman at a time when there weren’t many women producing. There was Gail Davies and Wendy Waldman, but female artists weren’t given that credit or that opportunity very often. Rodney watched me work with his band out on the road and, when I got a record deal, he said, "Listen, you know what you’re doing, so why don’t you and I producer this record together?" That was a very generous gift to me, professionally. I got to watch him work, and he’s a master at working with musicians and walking the line between spontaneity and craft.

And then there’s Garth Fundis, Dan Haas, and Josh Leo. I’ve really learned a lot from working with every one of those guys, but I also learn a lot from just the musicians I work with. In Nashville, we have an embarrassment of riches. You can pick up the phone and have these world-class musicians out to your studio in 24 hours. I’ve learned so much just picking the brains of Tom Bukovac, Michael Rhodes, and Jim Horn.

Does that factor into who you work with? Are you calling up people you want to learn from?

I think it has more to do with casting. You cast certain actors in certain roles for a movie and you cast certain musicians in a song. Or you cast them to complement an artist or create a rhythm section. But I’ve definitely reached out to musicians that I wanted to work with, just to tap into their genius. It’s all about collaboration. Very few records are made alone. Rarely is it a solo effort. It’s all about a team, and every team is going to look different: The collection of skill sets, the collection of experiences, the collection of wisdom … it’s all going to be different. What a producer does is make the most of whatever team they have the opportunity to work with.

In every context, the producer will have a different skill set or a different level of experience, even a different personality. Some producers bring a lot of technical skills and some bring more musical skills, but in the end, what it’s all about is having the intelligence and the humility to maximize the varied resources you’re applying to the project. And that’s what human beings do better than any other creature on the planet. We’re incredibly good at collaborating with each other and making the most of our individual potential. What can be accomplished by a group of human beings with a shared intention is formidable. That’s a lot of power to unleash. It’s beautiful.

For another female perspective on producing, read Stephen's conversation with Alison Brown.

Photo courtesy of Lari White