Over the past decade, The Po’ Ramblin’ Boys have established themselves as a modern voice in traditional bluegrass. They are equal parts researchers, archivists, and artists, continually reframing what it means to be “traditional” – with a particular focus on the ways that bluegrass and roots music have always been progressive and boundary breaking.

For BGS, I spoke via video call to mandolinist CJ Lewandowski and fiddler Laura Orshaw around the release of their new album, Wanderers Like Me. We talked about their unique approach and mission for the group, we covered a lot of ground, and I left the conversation feeling inspired to put more thought behind my own mission in music making.

I see that you are coming up on 10 years as a band. Many years ago I had the pleasure of writing a bio for The Po’ Ramblin’ Boys, and I’d love to know a bit about the way the band has developed and changed over the years?

CJ Lewandowski: I think we are all ten years older than when we started, for one, and that’s a lot. It started as four guys working at a distillery, you know, working a day job. … There was no traveling, no planning, no pushing to be something. And it naturally progressed. There were videos coming out and promoters started calling and asking us to come out and play.

A lot of people plan for stuff, and they push and push, and everything we’ve been involved with before this band was like that, plowing through clay. You push and you push and never get anywhere. Then this band just happened. We didn’t think we’d be traveling in a bus and going all over the world, but here we are!

Laura Orshaw: The coolest thing for me is seeing the material and the message of the band start to come together. Everybody is really interested in super regional groups from around where they grew up, or maybe just bands they got interested in, so the members have interesting and diverse listening palates.

For several years, the band was doing a lot of covers that people hadn’t heard before, drawing on that research. Then, for the past five years, we’ve been doing a majority of original material and I think that the conversations that it brings up within the band are new … like, “How did you come up with this?”

For example, a lot of the more recent songs are about traveling. … For me, I spin that from the women’s perspective, a lot of them are about mom or a woman waiting back home and I like to think about, “What if a woman sings this song?” I think a lot about those classic themes but making sure they’re relevant to the modern days.

You’re one of the few bands that has never changed their commitment to traditional bluegrass over the years. Tell me about that interest in maintaining your style and how to you resist the temptation to move in more commercial directions?

CL: We had a manager at one point and we were talking about different material we could cover, and I said, “I don’t know if that’s gonna fit us…” And he said, “Well whatever you play, you’re gonna play it the way you play, so it’s gonna sound like you.” I think about that a lot, because I think he’s right.

I try to stray from the word “traditional” and think more about “authentic.” It’s just the way we play, and the way we learned to play from the mentors in our home regions. Anything we do is going to sound like that. We just play and sing true to ourselves, it’s not a plan or an act, we kind of let it go with the flow

There has been pressure sometimes– maybe the band should push this way or that way, but all in all, it’s like, “Well, if it ain’t broke don’t fix it…” We are all just true to the way we play

LO: What CJ said, “whatever you do is gonna sound like you” – with the current album coming out, it’s the first time we’ve had a really heavily involved producer, Woody Platt (formerly of the Steep Canyon Rangers), working with us from pre- to post-production. I think five people are going to have their own opinion about every suggestion that comes up, but because of Woody we did try a lot of things that I don’t think we would have individually gone for. And after we all did them, we usually liked them.

CL: Woody had our sound in mind, and he said, “The main thing is, I want you guys to be you.” We spread our wings, we got a little more vulnerable. There’s a natural progression to all of this and this record is a great next step.

LO: It was just really refreshing to work with a producer and have that level of focus and excitement, having that external voice that studied and focused is huge.

Since the time I wrote your bio, Laura has formally joined the band, tell me about what she’s added to the group and how that came about? I think it’s such a magical fit, and really rounds out the sound of the band.

CL: Her first show with us was in December 2017 at the Station Inn and after that she did some sporadic shows with us and played on our next couple records. In January 2020, she joined full time and she has officially been with us for four/four and a half years now. We tried a lot of different fiddle players on the road and nothing fit quite like what she had on the table; the attitude, the drive, and the musicianship

I’m a huge fan of triple-stacked harmonies, like Jimmy Martin and Osborne Brothers, so she brought a completely different vocal opportunity to the group. There was us three guys, and we could do some three-part harmonies, but with her we could move to different keys and had a lot more flexibility. … And of course, her fiddle playing is sassy and full of energy.

A lot of people ask about the name, The Po’ Ramblin “Boys,” but there’s a tradition of that in bluegrass, with Bessie Lee playing with The Blue Grass Boys, and Gloria Belle with The Sunny Mountain Boys. I like playing into that. But it’s also the band saying, “Hey we aren’t limiting.” Like, whoever can cut the gig, we love you! We’re very open and try to be as inclusive as possible. There are a lot of demographics in the group and she just added another one. …

Bluegrass Unlimited dubbed us as being “progressively traditional,” and it’s true in that everything that is traditional now, once was progressive. I don’t try to stand on a soapbox, and it took me a long time to figure it out, but I’m a queer artist, and I didn’t have anyone to go to when I was figuring that out and I didn’t feel I had a place. So, a lot of the stuff we do today has an open mind to it. [I’m included in] an exhibit in American Currents at the Country Music Hall of Fame and I put a rainbow guitar strap in there just to say, “Hey we’re out here, and holler at me if you need something.” Because I didn’t have anyone to look up to in that way.

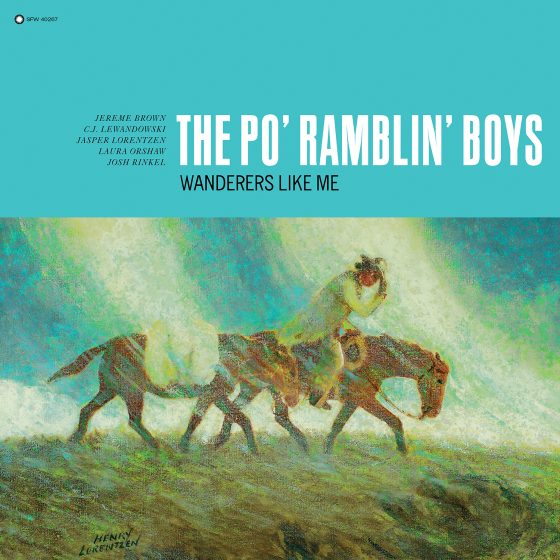

Can you tell me a little bit about the album art for this new record, Wanderers Like Me?

CL: The cover photo is a painting of a cowboy. It plays into the title and many of the songs on the record and goes back to the story of wandering all over the country. But that piece of art was painted by our bass player Jasper’s great-grandfather, who was a North Dakota scene painter born in 1900 who painted all the way until his passing. His artwork is in governors’ mansions, he was a very prominent artist and to include something like that for our album art is also another way of honoring tradition.

LO: The way I see bluegrass, it’s a truly American art form. just like painting scenes, it reflects the culture and the time that it was painted in. In a lot of traditional art forms, there’s a kind of preservationist stance, but I think as a band we don’t like to have that mindset as a way to hold up barriers, or to say we don’t like modern or progressive music. A lot of what is told about American and bluegrass history is through a very particular lens; it’s very easy to see a fuller picture when you start digging. We travel and meet a lot of people, we live in modern society, we all have a lot broader perspectives than the people creating music years ago.

So, we just see this mindset as a way to make the music reach its full potential. Preserve and broaden it by being aware of what’s going on around us, thinking about language and thinking about American art forms.

CJ: “Being you” is it’s own art form as well… There’s a lot to just making sure that you’re being yourself.

The people that we learned from, it’s amazing to learn at the knee or the foot of these incredible people, but it’s not a boundary. It’s something that you take and grow from and learn from. Not everyone is perfect or mindful… I learned good and bad from some of these folks. You learn what to do and sometimes you learn what not to do. You take it from spades and grow from that. We want to honor people, but also make this a better realm for everyone. Just because you play traditional music doesn’t mean you have to have a traditional mindset.

I think the fact that this record is coming out on Smithsonian Folkways says a lot about the timeless nature of the music you are creating. What do you hope that folks will get from your music now and also in the future?

LO: I think that one of the most neat things is knowing [Smithsonian’s] mandate around preserving music, knowing that everything that they have and archive will be there for ever. It will always be available.

CL: there’s a lot of good material out there that’s been overlooked. I call listening through it “digging for gems.” As an artist, I hope that one day when we’re gone… someone might find our music like that. I don’t have any kids, so I really think about how my music might be left behind for the next generation. With Smithsonian, we could be dead and gone and someone’s great-grandniece could ask for a copy of our record from the label and even if it’s out of print, they will print one copy and send it to them.

You have a lot of songs about the hardships and joys of travel and touring, do you guys see yourself touring for another 10 years?

CL: There’s a lot of different factors, I think we’d all like to go as long as we can, but within this 10 years we have fiancés, marriages, children, people living in different states. In 2018, when we got Emerging Artist of the Year [award] at IBMA, I looked at everybody and I said, “OK, if you want out, get out now.” And we all put our hands in and said, “We got this.” We all got together about how if one of us going leave, then we’d all let it go.

We never really felt like there was a place for us for a long long time, so when we found success we felt like, “Wow, we did this together…” I think the future is bright, especially with this new album.

Photo Credit: Michael Weintrob