Becca Mancari may live in Nashville, but the sound she’s developed in her music is anything but “Nashville.” It makes a good deal of sense, though, when you consider Mancari’s earlier life, which included stints in India, the Blue Ridge Mountains, south Florida, and Staten Island.

On her debut album Good Woman, Mancari weaves her myriad life experiences into a lush tapestry of gold-toned tales which, sonically, hew far more closely to dreamy California folk-pop than the tradition-heavy throwback country currently making the rounds in much of Music City’s music scene. In doing so, Mancari has transcended her status as a local favorite to that of a nationally acclaimed artist, songs like “Golden” and “Arizona Fire” earning her nods from major outlets like NPR and Rolling Stone.

Mancari is also one third of one of the most buzzed-about new bands of any genre — Bermuda Triangle. Alongside singer/songwriter Jesse Lafser and Alabama Shakes’ Brittany Howard, Mancari and Bermuda Triangle recently released a single (the Laurel Canyon-esque ballad “Rosey”) and have plans to tour intermittently throughout the rest of the year.

You have a new solo album. Can you tell me how the album first started to take shape for you?

The album, it’s my debut record. I’ve only had one song out, “Summertime Mama,” and now we have two versions, which I think confused people a little bit. But it’s so great, the idea of the power of one song. I had that one song do its work and time-and-a-half. Everything from Ann Powers featuring us last year with NPR for AmericanaFest — which is huge, she’s been a huge blessing in my life.

I decided I was going to take my time. I met a lot of producers and I just couldn’t get the right vibe. I noticed that this guy — his name is Kyle Ryan — he would be coming to our shows all the time. I know he’s a busy guy. He’s Kacey Musgraves’ band leader, and he’s also deeply involved in her recordings now. But he would just keep showing up and, by the last time, he had a notebook in his hand and was taking notes at my show. I went up to him afternoon and I go, “Hey man, you wanna get coffee?” So we did.

I actually had never really heard anything that he had done production-wise, but everything that he talked to me about, I was on the same page, from inspirations like Tame Impala to the way he is more of a Beatles fan and less of a — and this is not against the Nashville sound or the country way, but I just don’t feel like I fit in that world, and I didn’t want to make a throwback record. I would say he was like another member of our band. Tracking was all done by my live band. The only “studio” musician was a trumpet player that I had come in.

Did y’all do the actual recording in Nashville?

Yeah, we did it over at his studio, which is right behind his house, right close to Mas Tacos. Of course, there’s like a million studios everywhere. He makes gold, man. He’s incredible.

You mentioned how the Nashville sound of the current isn’t necessarily what you’re after or what you do, but it does seem like you’ve still been embraced by that fan base — which, granted, is pretty broad these days. What do you think it is about your music that still appeals to that contingent?

That’s a good question. I don’t know. I feel like we are so much of a family in Nashville, so I feel like that’s kind of playing into it. I have friends like JP Harris or Christina Murray or Margo [Price] — real country musicians — and they listen to other music, too. It’s not the only music they listen to, and I think that what I’ve noticed is that they’ve been excited to come to the shows because they’re like, “Hey, you’re doing something different on that steel. I don’t know what you’re doing, but I really like it.” I think it’s just refreshing, maybe.

I really don’t have any background in country music. I didn’t really listen to it growing up. I don’t know how to play it, even. I do think, though, that I love songwriters, and I’d say my greatest influences, when I was young and still now, are Bob Dylan, Neil Young, even John Prine. To me, these people are able to translate even in the indie world because they’re just great songs. You can kind of do whatever you want, when you have great songs. I let my guys take what I write and put the sounds to it, put the vibe on it, and that’s how we function as a band.

Since you’re an artist crafting such song- and lyric-driven music, do you have a tried-and-true writing process that you follow?

I do the traditional sit down and pull out my guitar and be by myself thing. “Golden” came to me in the night, which is fairly rare. I think one of the things I also like to do is I listen to one record over and over and over again. I was listening to Gillian Welch at the time when I wrote that song, and I just wouldn’t stop listening to it, and there was this one song — I think it’s called “Orphan Girl” and it’s not the same thing at all — but there’s this one note that I keep turning in my brain.

That’s how I kind of take melodies sometimes, where I’m like … it’s not their melody, but it’s a hearing thing. I write a lot as a hearer. I don’t know how to read music. I wish I did, but I don’t. I play it by ear and I always have. I’ve always been really sensitive to sound, so a lot of times, it’s sound. I write better when I’m in the car driving, watching things and hearing things. I also voice memo a lot, then I take it back and figure it out on guitar. So it depends. But a lot of it is from sound, for some reason.

Lyrically, the songs sound like they are very personal. Do you draw very heavily from your own life?

I think I do. I’m in awe of the John Prines of the world who write these stories, but they are very personal. I also try and allow space for somebody else’s emotions and feelings and thoughts. There’s an element of somebody wanting to take it for themselves. But yes, a lot of this record has an overarch of time and life in it. I think it’s just because it’s my first record, too, so there’s a lot of life in this one, including mine.

It sounds like you’ve led a pretty nomadic existence, moving from place to place and seeing lots of things. How do you think that transience, if at all, has influenced you as an artist?

Oh, man. When you grow up with parents like mine that just wanted us to see so much of the world … My first time leaving the country was at 14. Not many people get to do that. I went to Peru when I was a kid and experienced that and saw so much of another part of the world that we aren’t introduced to, oftentimes. I think that has helped me open my eyes to seeing the other side of things, with empathy and compassion, I hope.

It’s easy to forget, in the world that we live in. We become obsessed with our own stuff. But I do think that helped. I was talking the other day in an interview with Ann [Powers], and she was asking me about that. I got to live in India for a while, and my older sister lived there for five years. Just spending time around Hindi culture — which is so different than anything I’ve ever experienced. I can’t explain India. Even the way we made “Arizona Fire,” I feel like there’s an entrancing, kind of dream-like aspect to it where I did get inspired by the hypnotic, circular sound that is in traditional Hindi music. Traveling all over the country, seeing different ways of life, I feel like, if I could tell any young person, I’d say, “Go. Go see everything you can, because it’s going to seep into you.”

Going back to what you said about writing from a place of compassion and empathy … one thing I find myself wondering about anybody who’s releasing a piece of art right now is whether or not the political climate had an impact on those pieces. Did you find yourself feeling influenced by that, when you were writing some of these songs?

Yeah, there’s definitely some social aspects. “Devil’s Mouth” is very personal to me. It has my family involved in it. I had some even — I don’t know what the word is — baggage, or pain, I guess, from feeling like I’m on the outside of things, even being somebody that came out [as gay] pretty young, when it was pretty scary still. Those things are definitely reflected in there.

The current climate that we live in reminds me a lot of when I was little. There’s a lot of fear-based living. And there’s a lot of an idea of pushing us away from people who have really worked hard to be open. And even what happened just recently with DACA … I wrote a song with Bermuda Triangle, another band that I’m in, called “Tear Us Apart,” and it has everything to do with it. It’s actually really emotional for me to even get into right now because it deeply affects my family — my nuclear family of me and my girlfriend — and just the life we have. It’s a lot.

Right now, I feel like I have not even gone to those places yet to figure out how to have a voice. I just talk openly, and I will use my music however to defend people that are in trouble right now. And there are a lot of people that are, and a lot of people that don’t really understand what it’s like to be affected by the Trump administration. I grew up in a Hispanic culture, and it’s a scary time for a lot of us. I’ve been really upset for the last few days. I don’t even know how to explain it right now.

Well, on a more optimistic note, you did mention Bermuda Triangle. I haven’t seen people this excited about a new band in a while. How did y’all first start pulling this project together?

Oh, man. Thank God for the light-hearted things in life. We have serious songs — serious heartbreak, political things — but we are just so about having fun. If you’re ever able to come to a show, it’s just funny. Brittany is hilarious. I like to have a good time, and we’re all truly best friends. I hang out with them all the time. They’re the people I’m spending my life with. So it was just a natural progression. Brittany and I met each other four years ago, and we joke/believe that we met each other in a past life, all three of us. We talked to a psychic and she was like, “Oh yeah, you’ve known each other for forever.” So there’s a little element of mystery and fun and also just true friendship.

For us, what a wonderful time to be together and enjoy each other, and that’s what we want our shows to be like. I don’t know why I’ve read any of this stuff, but I’ve read some haters already, but Brittany is so special to people, and I get that. But the thing is, we’re also special to each other and she understands that. I think the world needs to understand that more, especially with us as women. We celebrate each other. We don’t compete against each other. We push each other to be better, and that’s what this band is about. We really truly love each other, and we really truly believe in each other’s music. We get to demonstrate that in the way we want to and not because we have to survive off this band. We all have our projects. Brittany is going to continue to blow our minds. Jesse has been the most underrated writer in Nashville for years, and I’m just so proud to see her finally get the attention she deserves. I’m just excited that this Triangle is going to give us an open door to have fun, but also to put out some really great stuff. Yeah, we basically met on porches drinking tequila and started playing music.

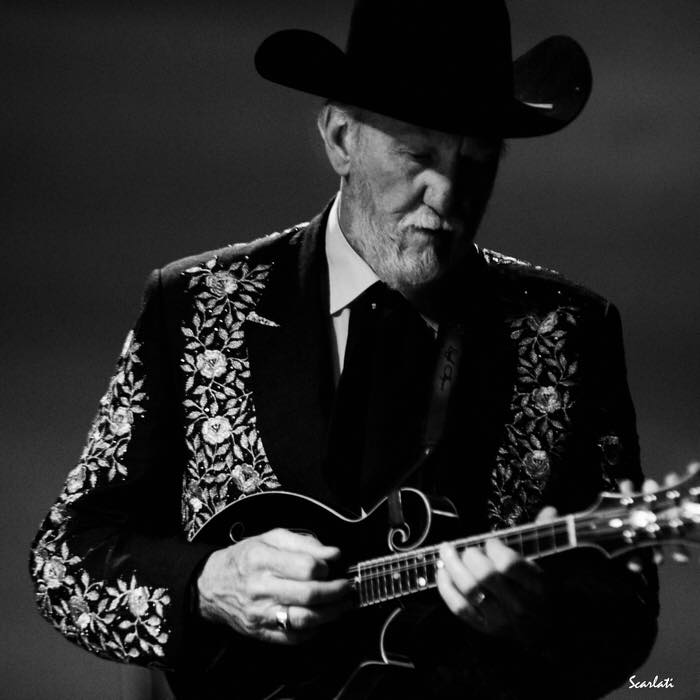

Photo credit: Zachary Gray