We usually think of musical traditions as being defined by their distinctive stylistic elements: the hard-driving string bands of bluegrass; the nimble, fingerstyle guitar figures of Piedmont blues; the rhythmically frisky washboard and squeeze box of Zydeco. It’s quite possible, though, for us to hear a kinship to country tradition in the music of two artists who serve two separate audiences in separate ways. That’s certainly true of Vince Gill and Margo Price — he, the mainstream country standard-bearer; she, the indie country newcomer. They may both incorporate time-tested textures like pedal steel guitar, but they belong to markedly different traditions of countrified emotional expression.

A classically trained singer who’s cultivated a tough vocal attack, Price musters a worldly brand of feistiness and hardship-withstanding resilience that takes significant cues from Loretta Lynn. And, much as Lynn’s down-home grit has come to command the admiration of a younger generation of rock-reared fans who value rawness and autobiographical authenticity — not to mention attract Jack White as a collaborator — Price’s music holds powerful appeal for that same crowd. It’s White’s Third Man Records that is releasing her bewitching debut, Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, an album that arrives with a vintage aesthetic and an underdog narrative: She had to part ways with her car and wedding ring to pay for it.

Gill, on the other hand, ranks as one of modern country’s finest, most tender voices — an openly emotional balladeer par excellence who’s equally at ease with honky-tonk weepers in the George Jones vein and sensitive, sophisticated adult-pop. That expressive range has long endeared Gill to popular country fans and made him a radio fixture through the ’90s. The same major label that was his home back then, MCA Nashville, just put out the immensely rewarding new set that he recorded in his home studio, Down to My Last Habit.

Though Gill’s singing and songwriting often exemplifies the softer side of country and Price stakes out spunkier territory, they had no trouble at all speaking across the divide.

Margo Price, meet Vince Gill. Vince Gill, meet Margo Price.

Vince Gill: Well, it’s great to hear from ya, Margo. Are you doing okay?

Margo Price: Yeah, I’m doing well. How are you?

VG: I’m just fine.

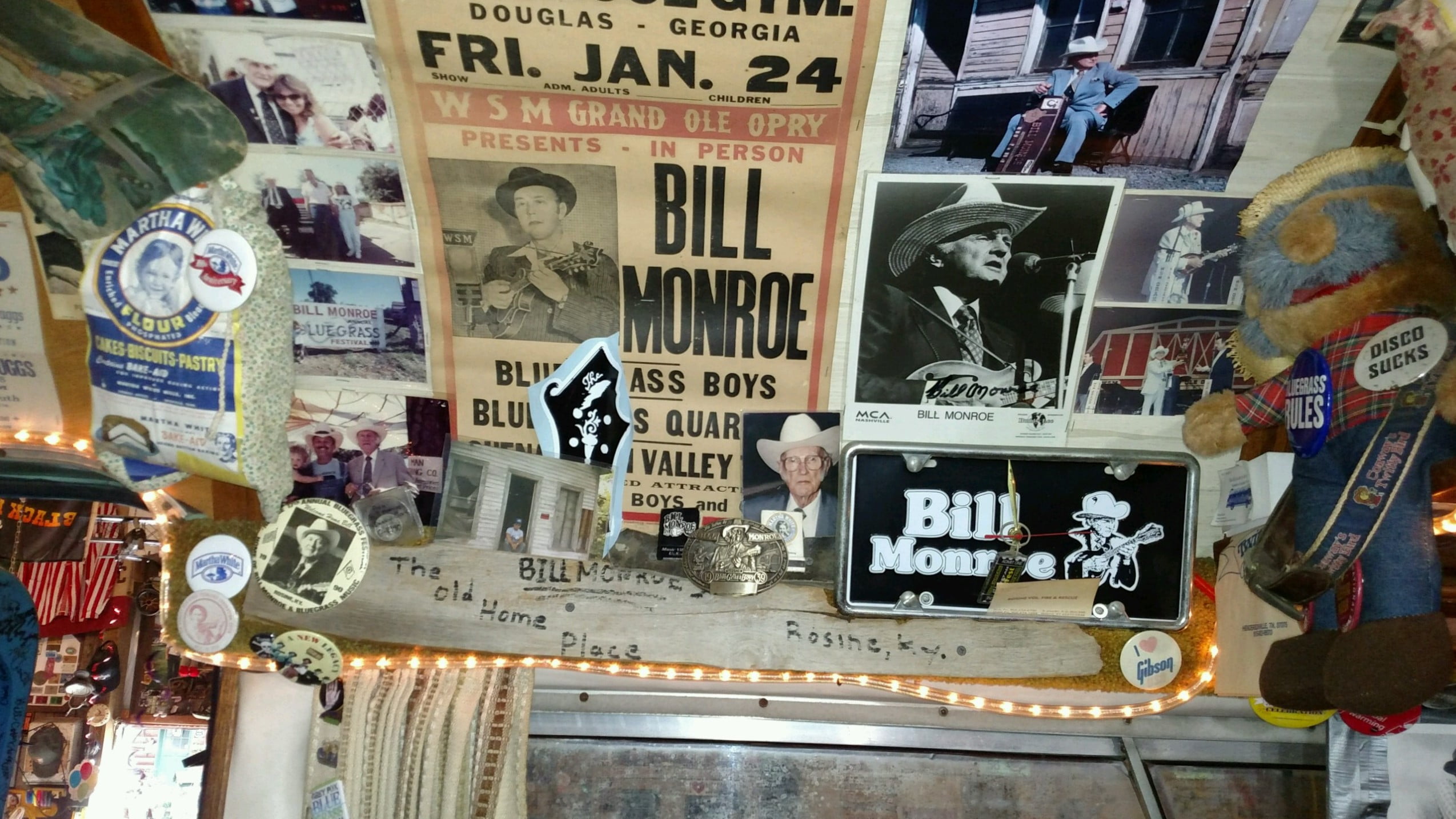

Before you got on the line, Vince, Margo and I were talking about the fact that she’s doing her very first Opry performance this Friday night.

VG: Oh, that’s awesome! It’s a big deal. You will never ever forget it, I can assure you.

MP: Thank you!

It just so happens that Vince is celebrating his 25 th anniversary as a member of the Opry very soon.

MP: Yeah, congrats!

VG: Aw, thanks. I’m just old.

[Both Laugh]

MP: Well, I’m pretty old to be making my first appearance on the Opry. Do you remember the first time that you played?

VG: I do, yeah. I got asked once to play the Opry, I think, in ‘88 or ’89. My daughter was in the second or third grade, and we were all set to do this talent show at school. She asked me to play guitar for her, so I taught her “You Are My Sunshine.” We practiced and learned it and had to make all the rehearsals. [The talent show] was all set for a Saturday night.

So I get this call from the Opry, and they said, “Hey, we’ve been watching your career. We want to invite you out to play the Opry.” And I said, “Awesome! When?” And they said, “Saturday night.” I said, “Oh, my God. I can’t make it. I’m playing at the Grassland Elementary School. I’ve gotta back up my kid.” So I kept my promise to my kid, and they invited me on down the line a little bit later.

MP: That’s really beautiful.

VG: Yeah, it was really cool. Jimmy C. Newman was the one who did the introduction, and I sang “When I Call Your Name.” That’s the first song I sang on that stage. I’d just written it and had hopes for it. I don’t even know if I’d recorded it yet.

MP: Wow, that’s really cool.

I love that we’ve begun this conversation with you two comparing stories. I’ll open with a question for both of you. I admit I almost feel silly asking this of a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame who is himself cited as an influence by so many singers. Here goes anyway: What country singer sets the bar for you when it comes to conveying emotion and being expressive?

VG: Go ahead, kiddo.

MP: Well, I have always been really drawn to a lot of singers of the ‘50s through ‘70s, especially women. Loretta Lynn, I think, is kind of where I’ve tried to set the bar. She could sing so tough, but she was always talking about something. I think Tammy Wynette, too. She could go one second from sounding really vulnerable and fragile to just kind of overcoming and somehow coming out strong, even though she didn’t feel that way. I think probably those two, and Dolly. The three of them I try to live up to, which is a hard thing to do.

What about you, Vince?

VP: One of the most emotional singers I’ve ever heard is Patsy Cline. You felt a tear in the way that she sang all the time. Then the earliest George Jones records. They sounded hungry. They sounded forlorn. They were full of melancholy. To me, that’s the epitome of a great country singer, is you honestly find the emotion, not necessarily through the words of a song but through the emotion of a singer. Come to find out, when I got to be great friends with George, he told me, “I was trying to emulate Roy Acuff.” If you listen to a Roy Acuff record, you hear him do the same kind of thing that George did, but George did it quite a bit differently, with some more soulful notes and bending notes a little differently. But there was a real similarity in them.

I remember when I was first starting to make country records, I wanted to be so traditional, but I was at a label that really wasn’t all that keen on having a real traditional roster. So I was a little bit lost. When I started on my first record, I was singing my heart out as best I could. My producer, Emory Gordy, graciously told me, “Listen, that sounds great, but we already have a George Jones. You need to find your voice. You need to find your way that you want this emotion to be conveyed. Don’t ever imitate. Be inspired by, but find your own voice.”

Vince, the most traditional-sounding song on your new album is the one you’ve dedicated to George Jones, “Sad One Comin’ On.” It’s a real weeper about being deeply affected by his singing in life and deeply affected by his passing. What went into that song?

VG: Just the truth. The greatest songs come from the truth. The truth was he lived every word of that song. All I had to do was tell his truth through my eyes. There’s one moment in that song where I really feel like I channeled him in a really beautiful way. In the last verse, there’s a line that says, “He’d tear your heart out when he sang a song.” Just the way that the word “tear” came out of my mouth, I wanted that to be an instant where it sounds like George.

Margo, I’ve read that you have an interesting connection to George Jones. Is it true that your great uncle is the songwriter Bobby Fischer, who wrote Jones’s “Writing on the Wall”?

MP: Yeah. He actually just had his 80th birthday. His daughter surprised him by getting everybody to sing songs that he wrote. Of course, I picked “Writing on the Wall.” That’s one of my favorites. It was so nerve-wracking. I sang it in front of him and Dickey Lee. George is probably the greatest singer of all time. It’s crazy that he lived the way he did and he could still belt.

Vince, you’ve joked that you cried like a baby at George Jones’s funeral. I was listening live on WSM that day, and I think you filled a really important role in the collective grieving process when you sang your song “Go Rest High on That Mountain” and got so overcome that you couldn’t get the words out.

VG: It was interesting, because I think it gave everybody the okay to let go. Before [I sang], it had all been so performance-oriented that, when I kind of lost it, it gave the room the ability to cry. … Truth be told, what really tore me up was hearing Patty’s [Loveless] voice — the sound of her voice and mine and the history of the two of us [singing together]. We were there getting up for George. So it was a combination of all those things: the passing of one of the true greats.

What’s it been like watching “Go Rest High on That Mountain” become a modern-day standard that people turn to for comfort?

VG: It’s pretty overwhelming, honestly. I was not gonna record that song back in the day when I wrote it. My brother passed in ‘93, and that was my way of honoring my brother and grieving for him and putting it in a song what I hoped was in store for him. I’m so grateful that we did choose to put it out. I guess people have said it’s become the modern-day “Amazing Grace” almost. … When people wanna turn to something you’ve gone and created, in their hardest of times, I can’t even describe how grateful I am [for that].

Not all the songs on your new album are melancholy, but a lot of them really testify to the depths of people’s feelings toward those they love or desire, those they’ve delighted in or let down or been wounded by. For you, how is that kind of sensitivity linked to mature expression?

VG: All I know is that all I’ve ever wanted was to be moved by music, not so much to be impressed. Certain voices can sing all the notes, all the runs, all the licks, or a guitar player can play every note in the book, and at the end of the day, you go, “Well that was impressive, but it didn’t do anything to stir an emotion in me.” That’s kinda what the whole point of it has been for me.

Margo, you were joking earlier that you’re belatedly reaching this point in your career. You’ve been grinding it out in small clubs for a dozen years now, something like that.

MP: That sounds about right.

Since this is your first album under your own name, it’ll be most people’s first chance to form an impression of what you do. The title you chose, Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, brings to mind Loretta Lynn’s Coal Miner’s Daughter. What appeals to you about drawing a connection between where you’re coming from and where she was coming from?

MP: It was definitely kind of a nod to her, and also a nod to the Beach Boys’ song [“Farmer’s Daughter”]. It just felt really good to be honest and say where I’m from. I wasn’t born in the South, and sometimes people wanna make a point that I’m not allowed to sing country music or something because of that.

There have been great Canadian country singers.

MP: Yeah. I mean, you’d be surprised when you look back. Connie Smith, she was from Ohio. But yeah, I think it was nice to say something simply about who I am and where I came from.

To get a little more specific, how did Loretta Lynn’s tough-talking tell-offs, songs like “Fist City” and “Don’t Come Home a-Drinkin” and so on, influence some of your songs, say, “About to Find Out,” for instance?

MP: [Laughs] That’s a very good comparison between the three that you just mentioned. That one [“About to Find Out”] definitely mirrors the attitude in her songs. I just always loved that she was able to talk about things and not shove an idea down someone’s throat, but maybe [show] the other side of the coin. “The Pill” and things that she really went out on a limb to do, that kind of writing and living on the edge excites me.

You sing from the perspective of somebody who’s lost the family farm, or who’s spent a weekend in jail, or who’s been kicked around by life and the music industry — someone who’s gone through all that stuff and is a scrappy survivor. That’s the persona I get from a lot of your songs. What feels right to you about singing from that place?

MP: I think, for so long, I was writing from a different point-of-view. That may or may not be why it’s working now and it wasn’t then. I think, like Vince said earlier, the best thing about songs is honesty. An honest song is a good song. I feel really confident when I sing it, because I’ve lived it. It’s a form of therapy, I think, to just get it out and wear my heart on my sleeve a little bit. Plus, everybody loves an underdog.

Have you noticed that people seem to really place a lot of importance on the idea that the hardships you’re singing about are literally your autobiography?

MP: … It’s been interesting that that’s what people want to talk about. I guess the songs are interesting. I think, when I was writing 10 or 12 years ago, I didn’t have a lot of life experience. Like Vince was saying earlier, when your brother passed and you wrote that song, you kind of go into survival mode of, “How do I make myself and other people able to cope with tragedy?” Through that, you get thicker skin and you move on and, hopefully, you can share some of what you’ve learned with the folks around you.

Vince, the way you use your voice — the vibrato and curlicues and bent notes — makes a tremendous difference in making people feel a song. What would you say it takes for you to put that tenderness across vocally?

VP: Well, I think that the key to great singing is when you don’t; it’s when you stop. And what I mean is, if there’s this long line of words, it’s kind of like breathing. You want the listener to be able to take a breath, too. So often singers will sing all the way across the end of a phrase, all the way through, so that they cover up where maybe the hi-hat ends or the guitarist does what he does or whatever. The point of it all is to make room for everybody. That includes the singer.

I think a voice is either interesting to you or it’s not. It’s not going to be more interesting to you if you can sing more notes or if you can sing louder or harder or what have you. … What’s funny is, most singers will find a thing that they think is their thing, their go-to thing. And, to me, it’s generally the least appealing thing that they do. [Laughs] I don’t know why that is, but I’m sure that’s true in my case, as well. There are some go-to things that I think are my thing and everybody will roll their eyes and go, “That’s not what it is.”

MP: [Laughs]

VP: So I don’t know that I’ve got the answer to what it is that I do that people are drawn to. I’m grateful that they are. I think it’s the ability to be subtle with what you’re trying to do.

Margo, you have that no-nonsense, tough vocal attack and hard-edged phrasing. People have compared it not only to Loretta Lynn but also Tanya Tucker, and I’d throw in Wanda Jackson, too. How do you feel like you summon toughness in your approach to singing?

MP: You know, I had so many years of classical training. I was in choir and sang a lot in church and my mom would drive me 45 minutes up to this voice teacher in the city. She would teach me all the things, but it really is about just the raw emotion underneath it. I’m sure I still use some of my technique here and there, but I don’t find myself over-thinking it, because that’s when I’ll mess up. Growing up, too, in the school choir that I was in, the choir director, she never wanted to give me solos. Every now and then I would get to be in an ensemble. It was just like Vince was saying — people either like your voice or they don’t. And I think some people really love my voice because it’s different and it stands out. I’m sure other people are just not sure what to think of it. It’s got its own thing. I don’t quite know how to explain what I do, I guess.

I’d love to close with another question for both of you. We’ve been talking about the emotional traditions that you’re each working in. How do you feel like masculinity or femininity shapes what you do? How do you make use of either in your expression?

MP: You wanna go?

VG: Go ahead, buddy.

You’re both so polite!

MP: I know. Too polite.

… I do love a lot of male musicians and songwriters. So I feel like there’s part of me that’s always been a little jealous of the way that guys have the ability to sing more powerfully. Sometimes there’s this misconception that women have to sing pretty. I guess I like a good mix of the two. I’ve kind of been trying to get back into exercising my head voice a little more, because I do use my belting chest voice a lot. Like I said, I have classical training and I would sing mezzo-soprano Italian songs. I really exercised that delicate, sweet voice. But I think that, for a long time, I’ve kind of wanted to do the opposite and belt things out like Hank or Merle or George — or even women who commanded it, even Etta James or soul singers that really drove it out. You know, you have to find a good balance that works for you. Hopefully I’ve landed somewhere in the middle of that.

VG: [Laughs] You’re asking a question about masculinity and you’re talking to a guy that sings higher than most women on the planet. I already sing like a girl.

I just think that the real key is more about the soul that you bring. You sing what’s appropriate for the song you’re singing. … All you really want to do is sound authentic when you’re singing. You don’t want to sound like, “Hey, I’m a country singer singing a rock tune. Hey, I’m a jazz singer singing a country tune.” I think that each song is gonna dictate the way you should sing it. You may wanna sing it hard, but that could be wrong. I think that it’s more a song to song choice. I can honestly say I don’t think anything about masculinity at any point when I’m singing.

[All Laugh]

I really appreciate you both being good sports about this.

VG: It was fun.

MP: Yeah.

VG: Margo, have a great Friday night. I’m happy for ya.

MP: It was really an honor to speak with you today. I’m not gonna lie: I was a little nervous.

VG: Don’t be!

MP: You’re so sweet.

Illustration by Abby McMillen. Vince Gill photo by J Wright. Margo Price photo by Angelina Castillo for Third Man Records.