Three hundred years ago just about now — May 7, 1718, so legend has it — representatives of the riches-minded colonial French Mississippi Company decided that a malaria-infested swamp in the crescent bend near the base of the river for which it was named would make a great place for a port settlement. Nouvelle-Orléans they called it.

Thanks to them, over the course of the next couple of weekends, not too far from that original settlement, you can find a spot where, depending on how the breezes are blowing, you will be able to hear five, six, maybe seven kinds of music all at once. This is music representing cultures from all over the world — from Haiti, from Mali, from Cuba, from Brazil, from Nova Scotia, from the bayous and prairies just a few hours away, and from Congo Square on the edge of that former swamp. Music originated by escaped slaves, by French refugees booted out of Eastern Canada, by Irish dockworkers, by free people of color and landed aristocrats, by Baptist celebrants and Catholic congregants and European Jewish immigrants. Oh, and of the indigenous tribes who were there long before the Europeans. Blues, gospel, country, rock, salsa, merengue, Celtic, hip-hop, bounce, rara, R&B, Cajun, zydeco, klezmer, funk, brass bands’ Mardi Gras Indian chants, and real Indians’ pow-wow chants. And jazz, of course, both traditional and modern, just for a start.

And while you’re standing there, in that same spot, you can savor the irresistible aromas of cuisine from just as many traditions, all blended together in ways that have come to be associated with this place, which we now know as New Orleans … though that’s a different story … or a different part of the same story, perhaps.

That spot is in the middle of the Louisiana Fairgrounds which, part of the year, is a horse-racing track, but for the last weekend in April and first in May, has for decades been the site of the famed New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. And this year, the event is marking the city’s tricentennial with a valiant attempt to showcase and celebrate all of the many cultures that made this city like nowhere else in North America, really nowhere else in the world. Technically, that’s always been part of the mission of what people refer to as JazzFest — its baker’s dozen of stages spread around the grounds hosting artists with connections to that heritage.

This year, that specific mission will be concentrated in a tent very near that mid-Fairgrounds spot. Most years, a Cultural Exchange Pavilion has hosted music, art, crafts, and workshops devoted to a particular country or culture with historic ties to New Orleans. Cuba was spotlighted last year, Belize in 2016, and Haiti, Mali, Brazil, and Native America among others featured in recent years. For the tricentennial, all of that is being squeezed into the pavilion, an ambitious, but fitting focus.

The late, great singer Ernie K-Doe was fond of saying that, while he wasn’t positive, he was pretty sure “all music came from New Orleans.” Hyperbole from a man who called himself the Emperor of the Universe? Well, a little, maybe. A more accurate statement might be that pretty much all music came to, and through, New Orleans. Heck, after hosting its first documented opera performance in 1796, the city was known as “the Opera Capital of North America” through the next century. And, if you roll your eyes when JazzFest announces its big name artist headliners — a crop this year including Aerosmith, Sting, Beck, Rod Stewart, Lionel Richie, and LL Cool J — well, how many of them would be making the music they make, if not for the powerful influences of music tied to the heritage of New Orleans and the surrounding region?

It was all pretty much in place, even before the city’s single centennial, as cultural historian Ned Sublette notes in the introduction to his definitive 2005 account of those first 100 years, The World That Made New Orleans.

“New Orleans was the product of complex struggles among competing international forces,” he wrote. “It’s easy to perceive New Orleans’ apartness from the rest of the United States, and much writing about the city understandably treats it as an eccentric, peculiar place. But I prefer to see it in its wider context. A writer in 1812 called it ‘the great mart of all wealth of the Western world.’ By that time, New Orleans was a hub of commerce and communication that connected the Mississippi watershed, the Gulf Rim, the Atlantic seaboard, the Caribbean Rim, Western Europe (especially France and Spain), and various areas of West and Central Africa.”

And with all of that came music, gene-splicing and mutating through the years, from the drumming, dancing, and singing of slaves, given Sundays off, gathering in what became known as Congo Square (in what is now Louis Armstrong Park, just across Rampart from the French Quarter) to the backstreets and brothels of the Storyville district down the street where Buddy Bolden and Armstrong played their horns and Jelly Roll Morton worked the sounds of Latin America — “the Spanish tinge” — into roiling piano adventures through the collision of rhythm & blues and country-blues in the years just after World War II that brought about the birthing of rock ’n’ roll in Cosimo Matassa’s J&M Studios right on the other side of Rampart.

As Sublette put it: “The distance between rocking the city in 1819 and [Roy Brown’s] ‘Good Rocking Tonight’ in 1947 was about a block.”

At the same time, that distance is a trip around the world. This year, it’s all in one little tent.

A few highlights of note from the Cultural Exchange Pavilion lineup:

Sidi Touré — The guitarist, singer, and songwriter from Bamako, Mali, is one of the leading figures in modern Songhaï blues, roots of which became American blues and its variations via slaves brought across the Atlantic and, in turn, influenced by American blues and rock.

The Cajun/Acadienne Connection — A special collaboration between descendants of French settlers relocated to the Louisiana bayou prairies after being booted out of Eastern Canada by the conquering British in1755, and descendants of those who managed to stay in Canada. The former is represented by the Savoy Family Band, Marc and Ann Savoy standing among the leading forces in the revival of once-oppressed Cajun music and culture joined by sons Joel and Wilson, who have brought their own vitality to the form. The latter comes via Vishtèn, a young trio from the resilient Francophone community on Easter Canada’s Prince Edward Island which mixes French Acadian and Celtic influences with overt nods to their Louisiana “cousins.”

Cynthia Girtley’s Tribute to Mahalia Jackson — The formidable Girtley, who bills herself as “New Orleans Gospel Diva” offers her homage to New Orleans’ (and the world’s) Queen of Gospel and force in the Civil Rights Movement who, two years before her death, was a surprise performer at the very first JazzFest in 1970 in Congo Square, singing “Just a Closer Walk with Thee” with the Eureka Brass Band, followed by a formal concert the next night in the adjacent Municipal Auditorium, which now bears her name.

Tribute to Jelly Roll Morton with special guest Henry Butler — New Orleans-born Butler has long been one of the leading keepers of the flame of the city’s great piano traditions, an heir to such greats as Prof. Longhair and James Booker. Here, he is featured in a set honoring Morton who, if not the inventor of jazz (as he was wont to boast himself), was one of its key innovators and promoters in its formative years.

Jupiter & Okwess — Hailing from the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s capital Kinshasa, dynamic singer Jupiter Bokondji and his forceful band have become an international force in modern Congolese music, as it’s taken to the global road recently, gripping audiences at festivals and clubs alike in Europe and North America.

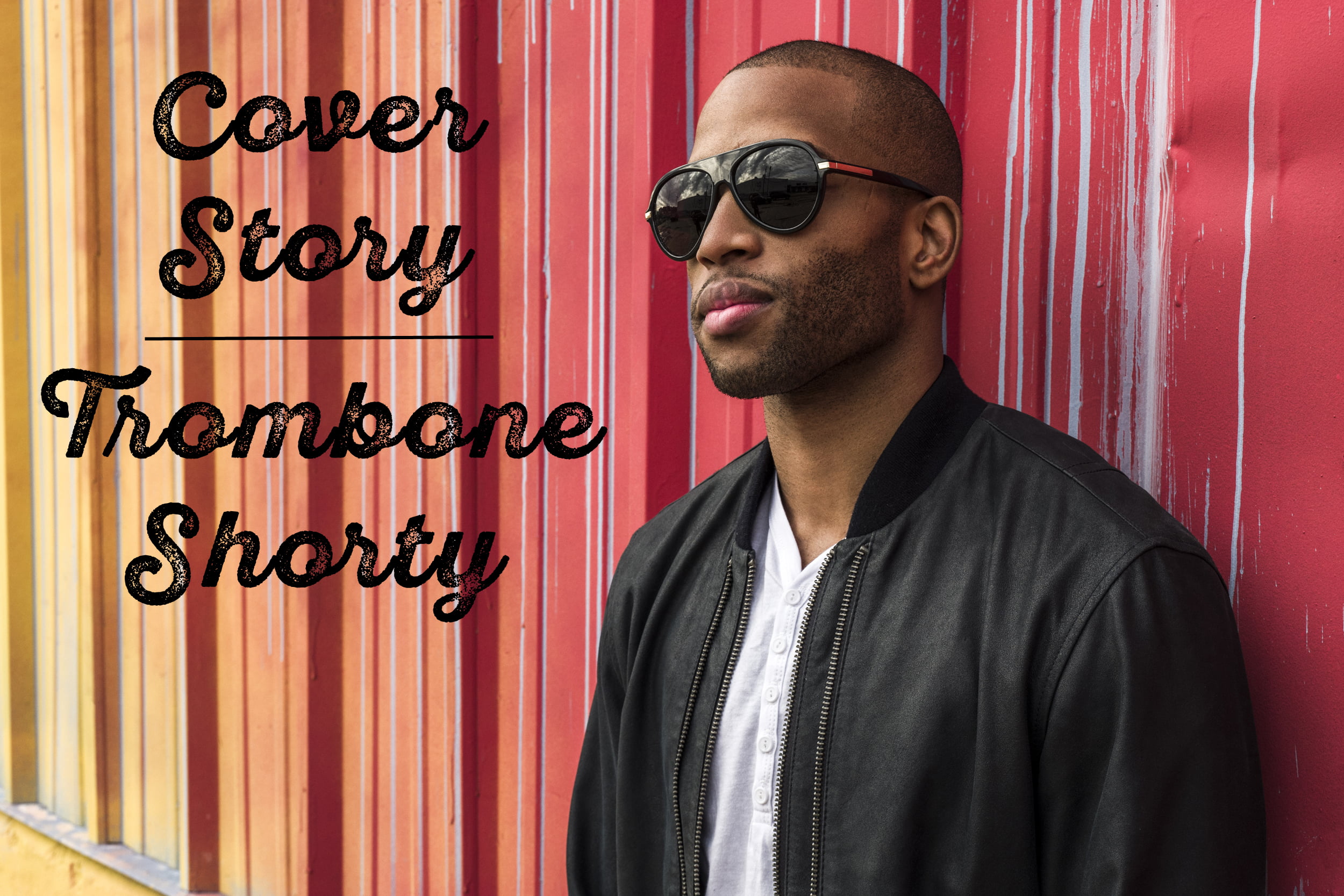

Kermit Ruffins’ Tribute to Louis Armstrong — Trumpeter and singer Ruffins became a star as a teen, helping lead a new generation of NOLA street musicians with the Rebirth Brass Band in the ‘90s, and has continued as a local favorite through his solo career (plus wider exposure via featured spots in HBO’s Treme, among other things). His love for and debt to the one-and-only Satchmo has always been a core presence in his playing and gravelly, good-natured vocal approach.

Leyla McCalla — The cellist, banjoist, and singer emerged in the second version of the Carolina Chocolate Drops alongside Rhiannon Giddens. Settling in New Orleans and starting a family, she’s dug deep into Haitian and Creole roots in her colorfully wide-ranging solo albums, showing herself a visionary, talented artist in her own right.

The East Pointers — Another young trio from Canada’s Prince Edward Island, this group draws more on the British-Celtic traditions, but with the distinct character of its home. Their latest album, What We Leave Behind, explores the sadness of young people leaving the island to seek work and wider horizons elsewhere.

Lakou Mizik — This Port-au-Prince group has been called the Buena Vista All Stars of Haiti, as it was formed after the devastating 2010 earthquake around a vibrant core of Haitian musical elders joining with rising youngsters. Their 2017 JazzFest performance was one of the year’s highlights.

Photo of Congo Square courtesy of New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival