Earlier this year, NPR Music published a behemoth piece — “Turning the Tables: The 150 Greatest Albums Made by Women” — saying, “This list … is an intervention, a remedy, a correction of the historical record and hopefully the start of a new conversation … It rethinks popular music to put women at the center.”

Viewing this sort of conversation through a bluegrass lens, staging our own intervention, remedy, and correction is critical. It’s true that we’ve reached several historic landmarks in recent years — Molly Tuttle was just named the International Bluegrass Music Association’s Guitar Player of the Year, the first woman to win the honor, and last year women won in the Fiddle Player of the Year and Mandolin Player of the Year categories for the first time, as well. Still, women are routinely marginalized by/within bluegrass. There are many bands that will not hire side-women pickers — the cliché “pretty good for a girl” is all-too common, even while it’s re-appropriated by women themselves. Also, there remains this overarching narrative that women are a recent, post-Hazel Dickens & Alice Gerrard addition to this genre. While often well-intentioned and placing well-deserved credit upon the influence of Hazel & Alice, this idea is false. Women have always been an integral part of bluegrass and the folk and roots music traditions that gave rise to it.

This list does not attempt to be exhaustive, complete, or comprehensive. We dare not be so bold as to claim that every important bluegrass album created by women is included. We are simply striving to illustrate the far-reaching, undeniable influence that these incredible artists have had on the music, as a whole. Each contributor, many of them groundbreaking, trail-blazing artists themselves, has chosen albums that are personally impactful. Glaring omissions and oversights are almost guaranteed, but therein lies the beauty of this conversation: This collection is merely a starting point, a springboard for a greater dialogue about the place of female creators, artists, musicians, and professionals in the telling of the history — herstory — of bluegrass.

At this present point on the bluegrass music timeline, diversity, inclusion, and openness are hot-button topics and they would not have been given even an inch of a foothold in our genre if it hadn’t been for the strength, determination, heart, and amazing music of the women below. — Justin Hiltner

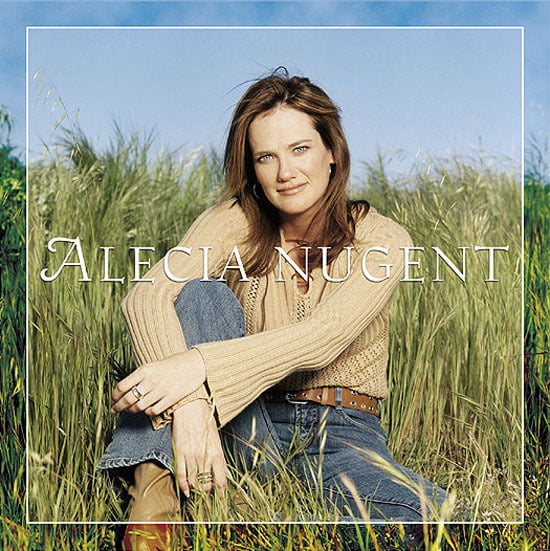

Alecia Nugent — Alecia Nugent

Though it was released by Rounder, Alecia Nugent’s debut originated as a self-release funded by a fan — just one token of the hold her strong, emotive voice can have on a listener. The Louisiana native turned to Carl Jackson for production, and the savvy Grammy winner put together a nifty cast of players and called on a crew of sympathetic harmony singers — including himself in both categories. Together, they picked out a well-balanced set of songs that included both Flatt & Scruggs and Stanley Brothers classics, but leaned largely toward gems from the catalogs of Larry Cordle, Jerry Salley, and Jackson, himself. Either way, Nugent’s voice carries an unmistakable feeling of urgency that makes every line believable and, when she cuts loose on a ballad, makes every note a world of hurt. — Jon Weisberger

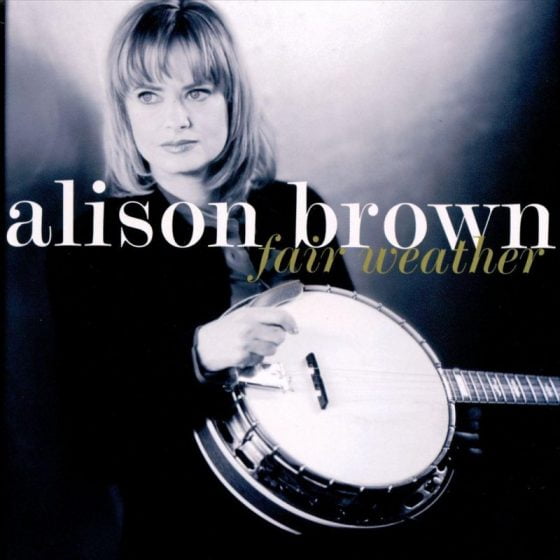

Alison Brown — Fair Weather

Let’s run down the cast of this record: Béla Fleck, Stuart Duncan, Tony Rice, Sam Bush, Vince Gill, Tim O’Brien, Claire Lynch, Missy Raines … and there are more. While Alison’s signature, outside-the-box playing style and modern aesthetic are at the center of this record top to bottom, the entire project is solidly bluegrass. “Poe’s Pickin’ Party” is a subtle nod to an actual party of the same name that openly excluded women from participating, on “Deep Gap” Alison plays Doc Watson-style guitar, and the burning double banjo tune “Leaving Cottondale” won Alison her first Grammy award. — Justin Hiltner

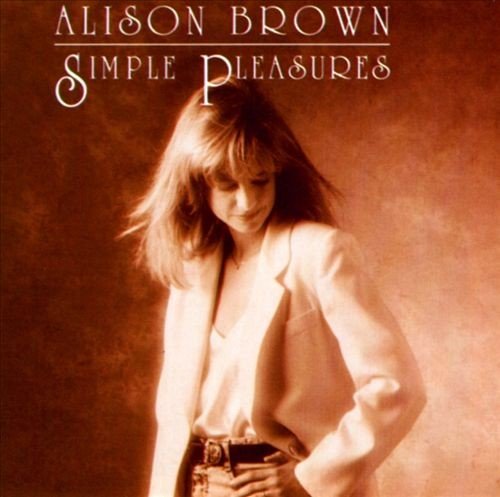

Alison Brown — Simple Pleasures

I had been playing banjo for a couple of years when I stumbled upon this album by Alison Brown while browsing through the tiny bluegrass section at a record store in the mall. It was the first time I had ever heard any banjo playing outside the bluegrass realm. I was completely fascinated, and my ears were opened to a whole new world of writing and playing. This record is the perfect example of how music that you digest during your most highly impressionable age and stage of development stays with you forever. She made a lasting impact on me by igniting a much-broadened awareness of what the banjo can do. — Kristin Scott Benson

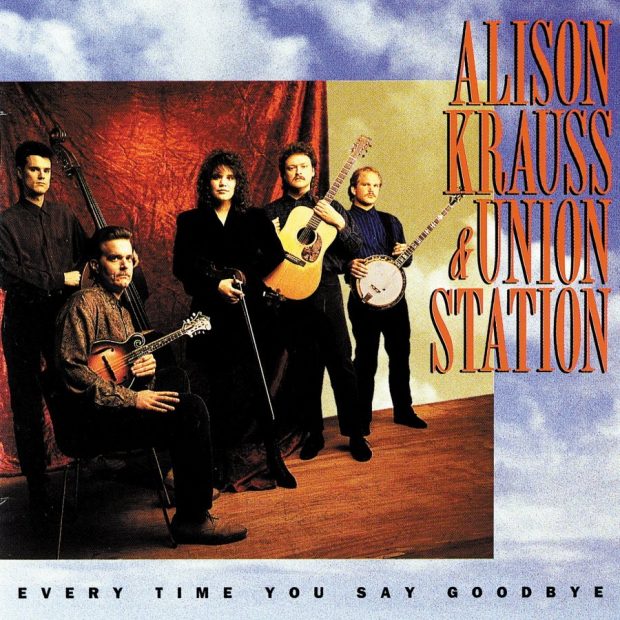

Alison Krauss & Union Station — Every Time You Say Goodbye

If the sound of Adam Steffey’s flawless mandolin intro to the title track doesn’t grab you immediately, then just wait about 20 seconds and you’ll hear one of the greatest voices the world has ever known. Every Time You Say Goodbye is one of my favorite albums from childhood. Even as an adult, I never grow tired of revisiting it. Alison has always been a genius at picking the perfect songs, making albums that really stand the test of time. From start to finish, I think it’s an amazing album — a must have for anyone’s collection! — Sierra Hull

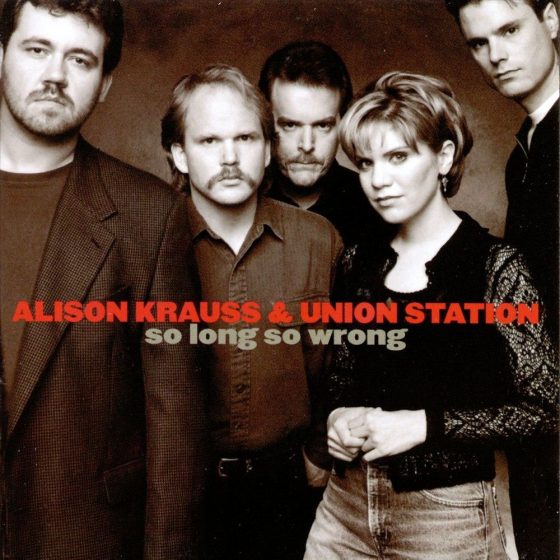

Alison Krauss & Union Station — So Long, So Wrong

“Looking in the Eyes of Love” may be the most popular song from this record — how many wedding playlists has it graced at this point, I wonder? — but in bluegrass circles, that very well could be the least important track on the record. You can still hear “The Road Is a Lover,” “No Place to Hide,” “I’ll Remember You, Love, in My Prayers,” and “Blue Trail of Sorrow” at jam sessions today, some 20 years later, played exactly like they sound here. And the sad, sad heartbreak songs on this album are nearly unparalleled. Try listening to “Find My Way Back to My Heart” in the wee hours of the morning on a solo road trip sometime. “I used to laugh at all those songs about the ramblin’ life, the nights so long and lonely, but I ain’t laughin’ now” will destroy you. It did me. — Justin Hiltner

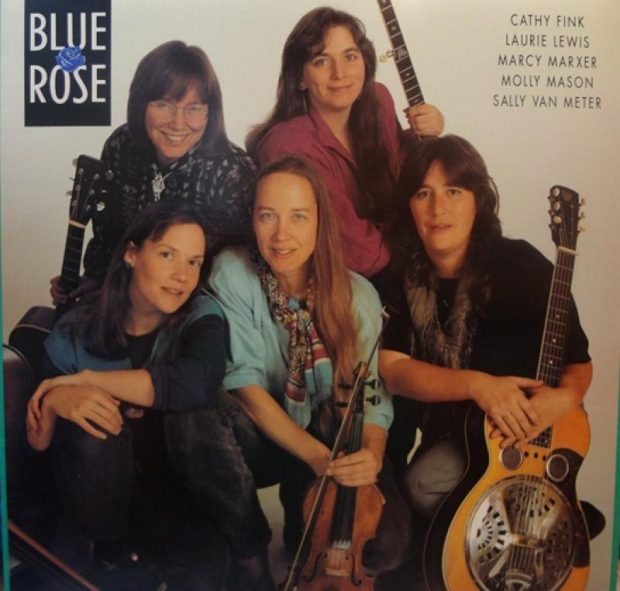

Blue Rose — Blue Rose

Blue Rose was the brainchild of Cathy Fink and Marcy Marxer, who noticed the “super picker” albums of the ‘80s never included any women. These talented women turned the tables with Blue Rose. When the group appeared on the Nashville Network’s New Country, the producer wanted to use male session players so Blue Rose would sound as good on TV as they did on the album. Cathy quickly disabused the producer of this notion and these talented women did their own picking. — Murphy Henry

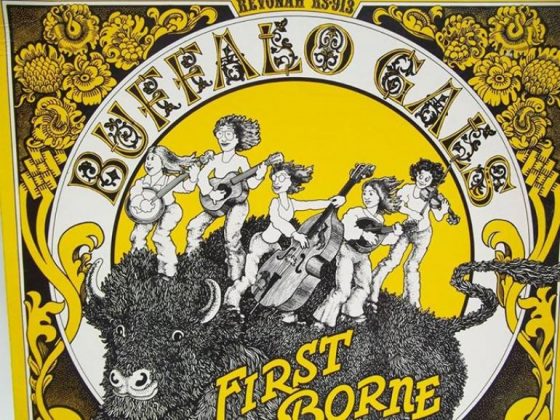

Buffalo Gals — First Borne

Martha Trachtenberg, Susie Monick, Carol Siegel, Sue Raines, and Nancy Josephson formed Buffalo Gals, the first-ever all-female bluegrass band, in the early ‘70s. They were largely regarded as a novelty act by promoters and talent buyers during their too-short run as a band — infamously, they performed an entire festival set in their sleeping bags on stage to protest being purposely relegated to the festival’s earliest performance slot. Their sole record, First Borne, is almost forgotten and sorely underrated, but should demand respect and recognition from all of us now. I mean, a bluegrass Carole King cover? Yes. — Justin Hiltner

Cherryholmes — Cherryholmes II: Black and White

“We had three strikes against us: We were a family band, we had kids, and we had women.” — Sandy Cherryholmes

Despite the “strikes” against them, I’ll never forget how Cherryholmes took my musical world by storm in the early 2000s. I first saw them play the Grand Ole Opry and was struck by the prodigy-level playing and mature voices of the Cherryholmes clan — including daughters Cia and Molly — in harmonies that can only be honed within a family. Even though the group disbanded in 2011, each of the family members continues to make their mark in various parts of the industry. Theirs is a sound I’ll not soon forget. — Amy Reitnouer

Claire Lynch — Moonlighter

Claire Lynch championed women through the ages with the writing of Moonlighter — an anthem to all who have ever tried to “have it all.” The music is pristine and the lyrics are timeless throughout. — Missy Raines

Claire Lynch — North by South

North by South by Claire Lynch is creative and, at the same time, quite bluegrass-y. I find myself putting this one on over and over again. — Gina Clowes

The Cox Family — Beyond the City

When a member of Counting Crows writes the liner notes for a bluegrass album, it will grab your attention; when it is an album by the Cox Family, it will grab your heart. Without question, the focus on Beyond the City (and any other album from the Cox Family, for that matter) is the universal love for that pure family harmony that comes from sisters Evelyn and Suzanne, brother Sidney, and father Willard. Suzanne and Evelyn were two of the most influential female voices in bluegrass during the ‘80s and ‘90s, and one listen to Beyond the City exemplifies why. From Suzanne’s bluesy, adventurous vocals on “Lovin’ You” and “Blue Bayou” to the sweet, ethereal tone of Evelyn’s voice on “Lizzy and the Rainman” and “Another Lonesome Morning,” it is easy to see why singers from Alison Krauss (who produced the album) to Flatt Lonesome’s Kelsi Harrigill and Charli Robertson point to the Cox Family as major influences of their own sound. — Daniel Mullins

Dale Ann Bradley — Catch Tomorrow

Dale Ann solidifies her place in bluegrass history with this album. Her voice is perfect, and the material is memorable. Contemporary and fresh without forgetting its bluegrass roots. — Megan Lynch

Dale Ann Bradley — Don’t Turn Your Back

While Dale Ann Bradley’s voice is as big and as lonesome as the mountains which she calls home, few female artists in bluegrass are as adaptive. A bold claim to be sure, but one needs to look no further than Don’t Turn Your Back for confirmation. Her influences are all over the map and she embraces the variety. Songs originally performed by Tom Petty, Flatt & Scruggs, Hoyt Axton, the Carter Family, and Patty Loveless appear next to original compositions, making for a musical palette atypical of your standard bluegrass album. From the sensitivity of “Will I Be Good Enough” to the sassiness of “I Won’t Back Down,” Dale Ann’s versatility showcases her depth of both musical mastership and emotional complexity. For me, though, Dale Ann is at her best when she is lonesome, as exemplified on the old mountain ballad, “Blue Eyed Boy.” — Daniel Mullins

Dale Ann Bradley — Somewhere South of Crazy

While it might seem pretentious to talk about terroir in the context of bluegrass music, when I listen to Dale Ann Bradley sing, I feel like I can hear the soul of eastern Kentucky coming through every note. Dale Ann’s music is very much the product of the contrast in her upbringing — a ‘70s childhood set against the backdrop of rural Knox County — and I’m particularly proud of Somewhere South of Crazy for the way it weaves those disparate influences together. A pop-grass version of “Summer Breeze” sits comfortably alongside the traditionally rooted “In Despair,” and the haunting trio of Sierra Hull, Steve Gulley, and Dale Ann on the thinly veiled war protest song “Come Home Good Boy” is timeless. — Alison Brown

Della Mae — This World Oft Can Be

How many bands do you know of that went from their inception to a Grammy nomination in just four years? This fact is just so much more delicious knowing that Della Mae’s name itself is poking fun at the type of testosterone-fueled, mash-heavy, boy’s club bluegrass that has deliberately excluded women for so long. And each of the incredible Dellas are excellent musicians — no “pretty good for a girl” qualifiers necessary. The music on this record teases the edges of bluegrass open, with old-time fundamentals, straight-ahead ‘grass’s drive, and poetic, literary lyrics. It’s truly an important moment in the history of women in bluegrass. — Justin Hiltner

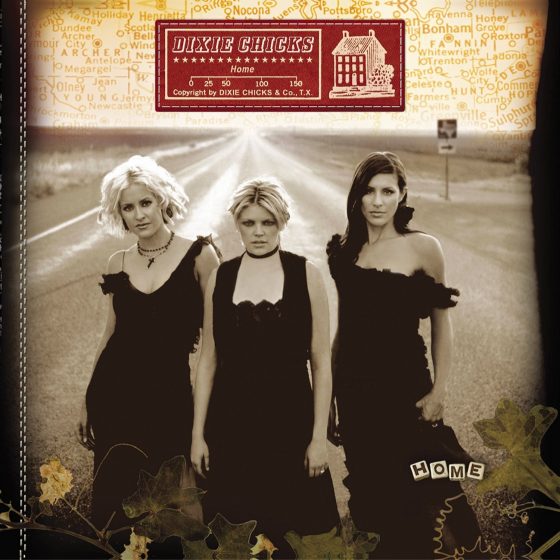

Dixie Chicks — Home

When this record came out, I was an insecure, high school-aged girl. Because of this album, I was finally able to feel cool and proud telling my friends I play the banjo and spend my weekends at bluegrass festivals. It’s full of energy, tasty licks, tight harmonies, and good, catchy songs, and it has reached an audience that most bluegrass albums never will. — Gina Clowes

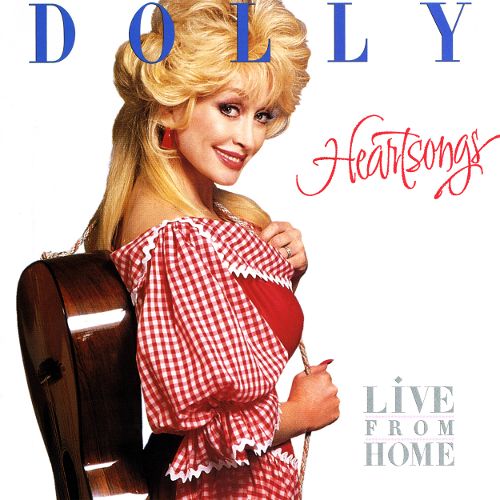

Dolly Parton — Heartsongs

This was one of the most influential records to me growing up. I remember singing along with and trying to pick out every harmony part that I could find as a little girl, playing the tape over and over to do so. Hearing two more of my favorite singers, Alison Krauss and Suzanne Cox, on harmonies made it extra special. — Kati Penn-Williams

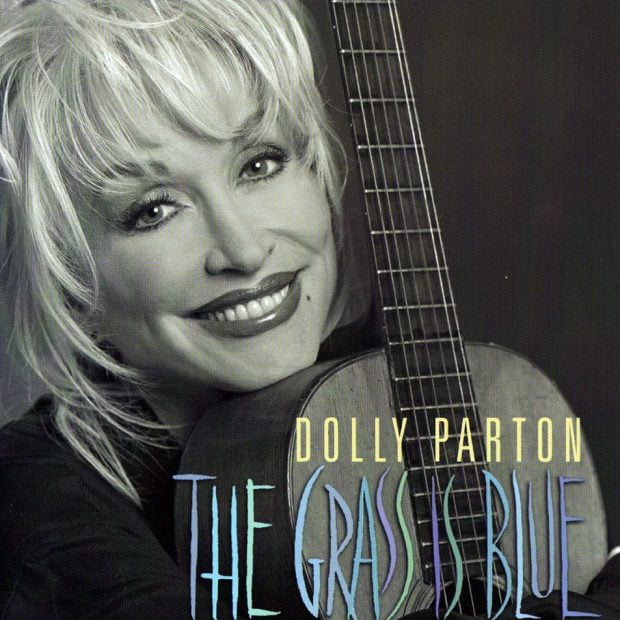

Dolly Parton — The Grass Is Blue

First off, who doesn’t love Dolly? She’s kind of the ultimate artist, in my opinion. She’s one of the greatest songwriters to ever live, yet she can take a song she didn’t write and sing it from a place of sincere honesty like no other. From the downbeat of “Travelin’ Prayer” to Dolly’s first soaring high note (just listen to the huge tone she pulls!), I am sold. The production on this album is as slick as it gets, while still retaining that bluegrass grit that keeps you on the edge of your seat. She’s surrounded by an all-star band made of up of some of my biggest heroes, and I believe any musician can learn a lot from this album. — Sierra Hull

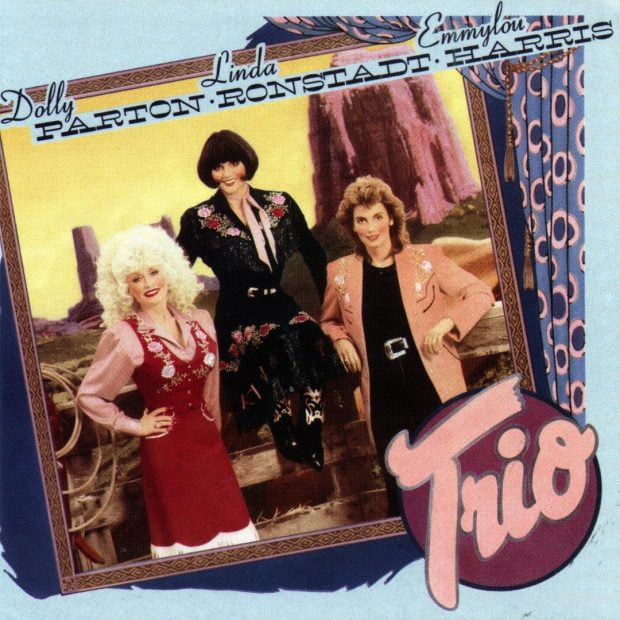

Dolly Parton, Linda Ronstadt, & Emmylou Harris — Trio

Dolly Parton, Linda Ronstadt, and Emmylou Harris have long established themselves as powerhouses in popular music. It is only fitting that their first album together, aptly named Trio, showcases the depth of collaborations between these master artists. Having been long-time admirers of each other’s, as well as having covered one another’s songs on respective albums, the trio presented incredible harmonies and musicianship that set Parton, Ronstadt, and Harris ahead of the pack. It also succeeded in inspiring future generations of female badasses in country and bluegrass music (Lula Wiles, I’m With Her). Winner of two Grammy awards, Trio remains a tried and true collaboration between legendary musicians and visionaries. — Kaïa Kater

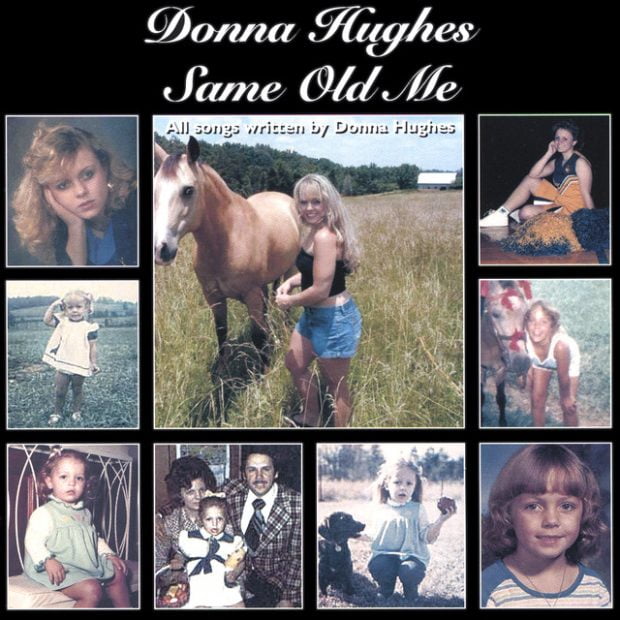

Donna Hughes — Same Old Me

With 21 original songs, songwriter Donna Hughes’s second album, Same Old Me, introduced her as a prolific force within the genre. With each listening, I am struck by the intimate way this recording captures a feminine voice leading a hard-driving configuration in the studio featuring Adam Steffey, Scott Vestal, Clay Jones, Greg Luck, Ashby Frank, Zak McLamb, Alan Perdue, Joey Cox, and Gina Britt-Tew. Donna juxtaposes B-chord, jam-style bluegrass with introspection centering around the oft-displaced female voice — something few albums have accomplished since. — Jordan Laney

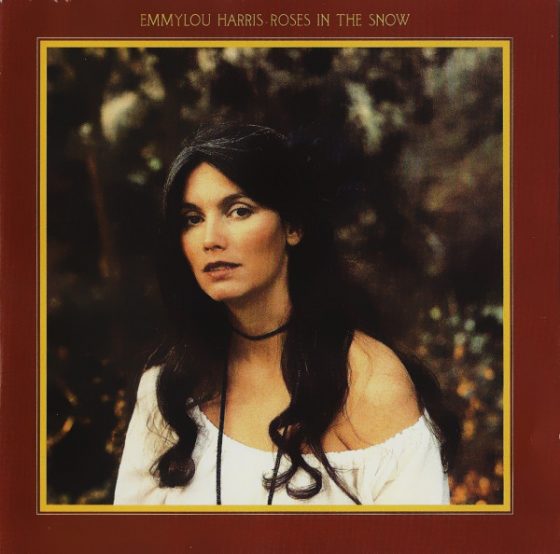

Emmylou Harris — Roses in the Snow

While Emmylou is not known as a bluegrass singer, per se, Roses in the Snow made an enormous impact on the bluegrass world by opening a wide door for many new-to-bluegrass-fans to come through. After its release, I remember years of hearing Roses in the Snow added to the common festival scene playlist. Her fresh take on “Gold Watch and Chain” and “I’ll Go Stepping, Too,” as well as others, brought new life to these bluegrass treasures. — Missy Raines

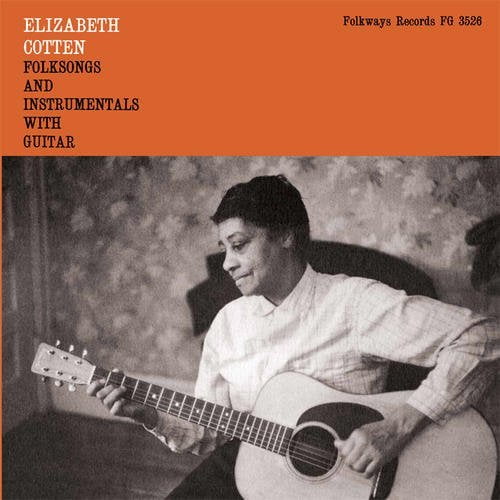

Elizabeth Cotten — Folksongs and Instrumentals with Guitar

Featuring songs like “Freight Train,” this seminal Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten album influenced the 1960s folk “re-awakening.” A mix of traditional and original songs, this 1958 release showcased Cotten’s signature left-hand guitar and banjo-picking styles. Mike Seeger’s recordings of Cotten, released on Folkways Records when she was 62 years of age, cemented her as a true matriarch of folk and blues. “Freight Train,” written when Cotten was only 12, has been covered by the likes of Paul McCartney, Peggy Seeger, and Joan Baez. — Kaïa Kater

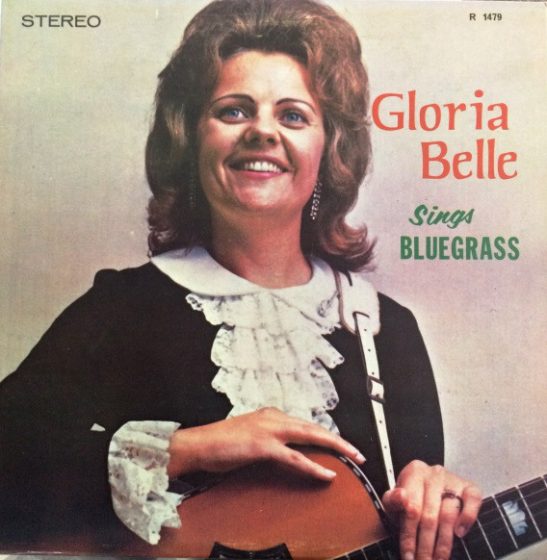

Gloria Belle — Gloria Belle Sings and Plays Bluegrass in the Country

Perhaps best-known for her long stint with Jimmy Martin’s Sunny Mountain Boys in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, Gloria Belle is a fine singer, guitarist, mandolinist, banjoist, and bass player. In 1968, she released her first album as a band leader following singles that featured her mandolin playing. While she succeeded this debut with several more fine albums as a leader, this album features not only her powerful singing but her instrumental mastery, as well, playing lead breaks on banjo, mandolin, and guitar. — Greg Reish

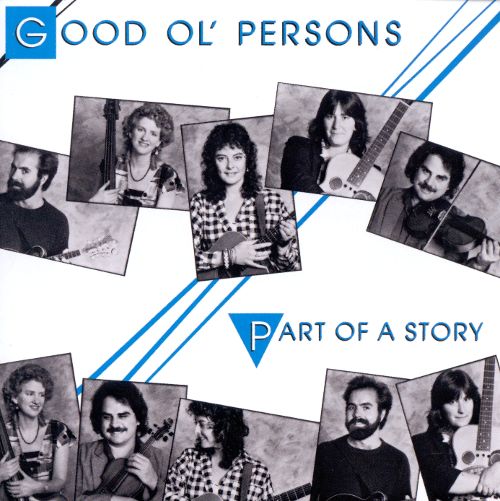

Good Ol’ Persons — Part of a Story

The 1970s California bluegrass scene was fairly devoid of female players and singers, and the Good Ol’ Persons were a beacon of light for many distaff pickers — including me. In many ways, I think the Good Ol’ Persons foreshadowed the more gender-balanced bands that are coming up these days. Kathy Kallick, Sally Van Meter, and Bethany Raine were three-fifths of the band that recorded Part of a Story in 1986 for Kaleidoscope Records and, more than 30 years later, I still find myself coming back to this album. There is something loose and playful about their groove, a feel that separates a lot of California bluegrass of that time from its Appalachian cousin. The gorgeous melody of the title track has stuck with me across decades, and the ecumenical message of “Center of the Word” captures an open-mindedness that I associate with that time and place. — Alison Brown

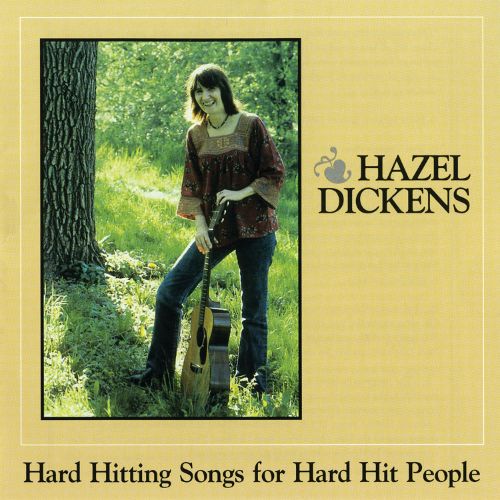

Hazel Dickens — Hard Hitting Songs for Hard Hit People

Many may argue that bluegrass is apolitical, but not when Hazel Dickens is singing. Despite this year’s induction into the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) Hall of Fame with Alice Gerrard, Hazel’s solo work has yet to receive recognition for its monumental role in songwriting and activism within bluegrass, evoking the political, gendered, and “hard hitting” side of rural life. This album, in particular, continues to offer generations the anthems needed to gather and rally. From “They’ll Never Keep Us Down” to “Scraps from Your Table,” there is nothing hidden about Hazel’s message here: Fighting for the rights of workers and revealing inequity can — and should — be done through song. — Jordan Laney

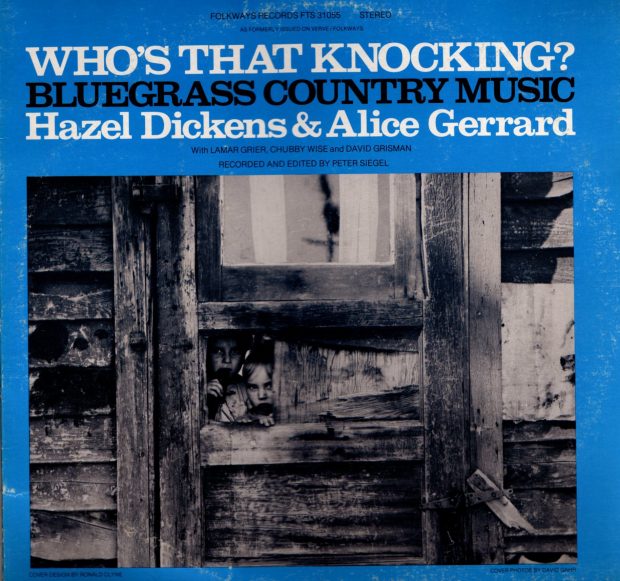

Hazel Dickens & Alice Gerrard — Who’s That Knocking?

I first heard this 1965 album in 1974, and it knocked me out. Hazel & Alice really seemed to capture the high lonesome sound of the Stanley Brothers and Bill Monroe, and the back-up band of Chubby Wise on fiddle, Lamar Grier on banjo, David Grisman on mandolin, and Fred Weisz on bass was a joy to listen to. By today’s standards, it’s pretty rough and rocky, but I read somewhere that the recording budget was $75 … so there you go. I became an instant fan. It was the first recorded example, for me, of women really capturing what I considered to be the bluegrass sound. — Laurie Lewis

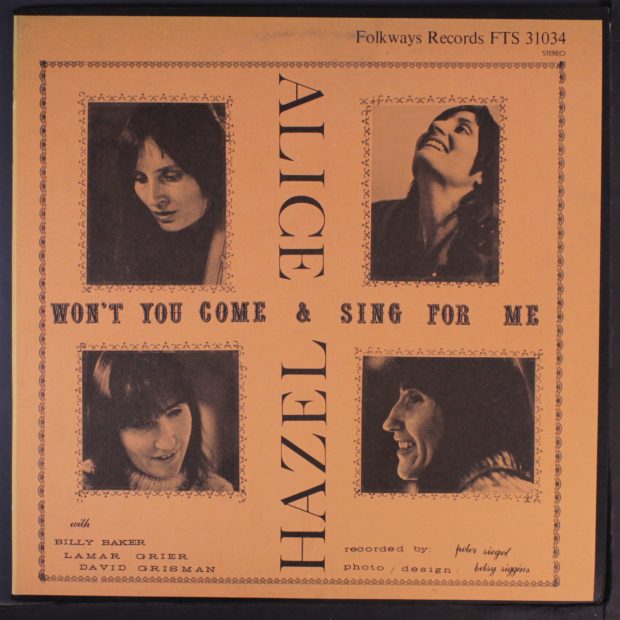

Hazel & Alice — Won’t You Come & Sing for Me

When I first started playing bluegrass in 1975, there were two women who were role models: Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard. Every woman who was coming into the scene listened to the two albums they made in the ‘60s, and they were a frequent source of material, as well as being huge inspirations. Over the years, Hazel & Alice were heroes, role models, icons, and, eventually, dear friends. I feel lucky to have crossed paths, sung a bit, and laughed a lot with each of those women! — Kathy Kallick

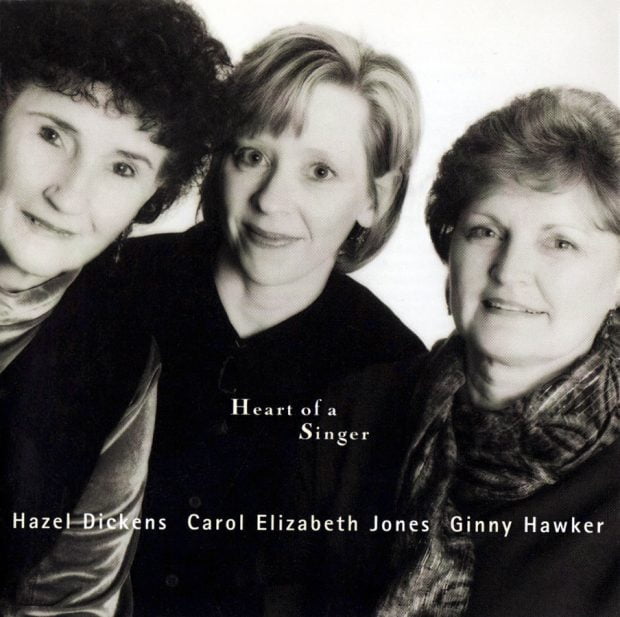

Hazel Dickens, Carol Elizabeth Jones, Ginny Hawker — Heart of a Singer

Three generations of Appalachian women sang together for the first time in the lobby of the good ol’ IBMA. Hazel hadn’t made a record in a decade, but this trio felt special. “The thing that took the longest was choosing the songs,” said Carol Elizabeth, whom I called on a recent night drive to confess my love for this turn-of-the-century masterpiece. It took a year-and-a-half of weekend “marathon singing sessions” to find a batch that checked the boxes — great for harmonies with a story they could stand behind. “Hazel really wanted to sing songs where the women are strong.” Heart of a Singer was recorded in two sessions, one on either side of the birth of Carol Elizabeth’s daughter, Viv Leva (who is now pushing 20 with a forthcoming album that I’ll call an early contender for the next edition of this very list). — Kristin Andreassen

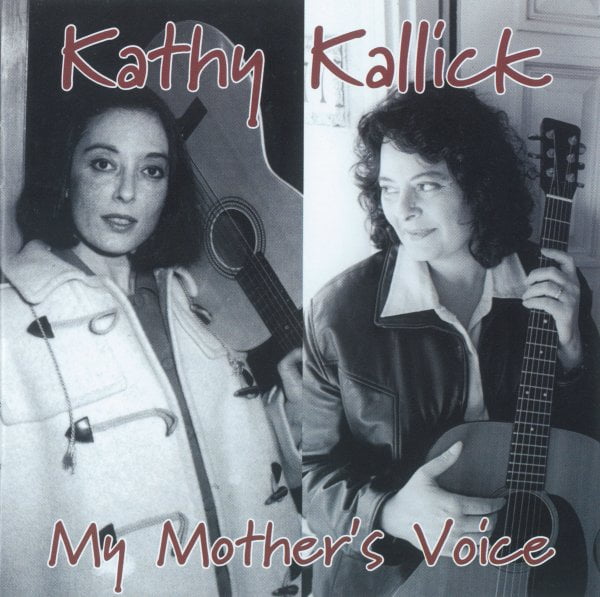

Kathy Kallick — My Mother’s Voice

This is such a beautifully personal album. I love Kathy’s original songs, but these that she learned from her mother tell you everything you need to know about her passion for traditional music. — Megan Lynch

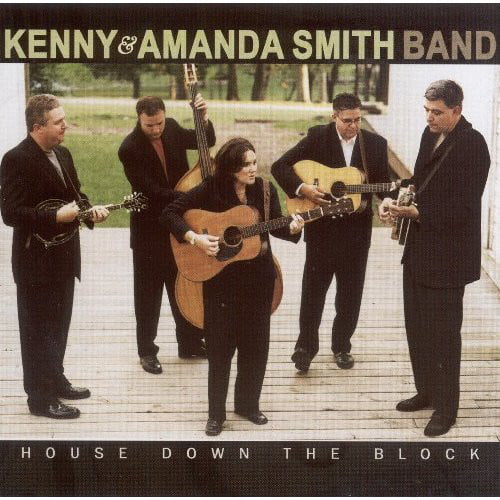

Kenny and Amanda Smith — House Down the Block

When I first heard this record, Amanda’s voice hit me square between the eyes, and I was mesmerized by the choice of material. It really opened me up to the middle ground between covering, for instance, “How Mountain Girls Can Love” and esoteric mid-2000s Alison Krauss songs. — Megan Lynch

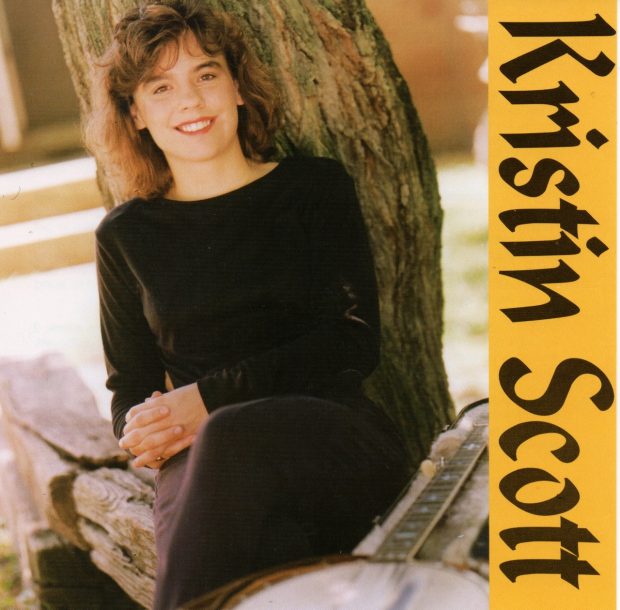

Kristin Scott — Kristin Scott

Kristin’s very first album was a cassette-only release, I think, but it had a huge impact — showing that instrumental prowess and instrumental albums were not just the territory of guys. She blazes through “Follow the Leader” and shows off her more wide-ranging musical tastes on tunes like “Bye Bye Blues” and “Charmaine.” — Casey Henry

Laurie Lewis — Love Chooses You

With songs like “Hills of My Home” and “When the Nightbird Sings,” Laurie Lewis created a masterful blend of traditional bluegrass and Americana. This record encouraged and inspired me to honor all of the influences that were brewing within me. — Missy Raines

Laurie Lewis — Restless Ramblin’ Heart

Great songs and aggressive fiddling! This album was the first Laurie Lewis record I owned, and it was the beginning of my journey to become a bluegrass musician. — Megan Lynch

Laurie Lewis & Kathy Kallick — Together

This duet album from these two powerful West Coast women includes Kathy’s song “Don’t Leave Your Little Girl All Alone,” one of the few bluegrass songs in which the ailing mother does not die! They also dedicate “Gonna Lay Down My Old Guitar” to Hazel & Alice with thanks for “breaking trail.” — Murphy Henry

Leyla McCalla — A Day for the Hunter, a Day for the Prey

Having drawn a bit of courage from her time in the Carolina Chocolate Drops, Leyla McCalla ventured out with her own voice on A Day for the Hunter, a Day for the Prey. She felt compelled to not just tell the tales of Black America, but to tell the tales, specifically, of Black Haitian and Creole America. Those are her roots and she wanted to dig them up. Using a cello here and a banjo there, McCalla’s musical — and lyrical — languages bob and weave however they must to remain true to their subjects. And captivatingly so. — Kelly McCartney

Lynn Morris Band — Shape of a Tear

Lynn’s music is so down to earth, so unpretentious, and just so darn tasteful. While any of the Lynn Morris Band’s albums could easily be included on this list, I think she really out-did herself on Shape of Tear. — Gina Clowes

Lynn Morris Band — The Lynn Morris Band

I started hearing about Lynn Morris in the 1980s, when she was playing with Whetstone Run. Lynn had a wonderful knack for finding material outside of the traditional bluegrass repertoire and turning those songs into bluegrass classics. She was a powerhouse guitar player and a ferocious banjo player, having won the National Banjo Championship in 1974. The fact that she was so accomplished as a musician and couldn’t earn a place in a good band irked her, and she was never completely comfortable leading her own band. Still, she was a wonderful front person, warm and personable, and her voice was heavenly. I had a long conversation with her in the early 1990s about her style of band leading. She took that job very seriously, and she was working with men who were often uncomfortable with her leadership role. She had to hold authority without complete support and that was challenging. She pushed the band hard, with long drives, often with a detour of several hours to play live on the radio or anything else that would promote the band. It paid off, as she was named Female Vocalist of the Year by IBMA, won Song of the Year with Hazel Dickens’ song “Mama’s Hand,” and her bandmates went on to win IBMA awards, as well. — Kathy Kallick

Molly Tuttle — Rise

Molly Tuttle’s 2017 release, Rise, gives me hope for the future of this genre. She’s not only a formidable singer, songwriter, and band leader, but is the first female to win IBMA’s Guitar Player of the Year award. (’bout damn time, amiright?) Her sound is mature and focused, making it a beautiful reflection of the future of bluegrass. — Amy Reitnouer

Ola Belle Reed & Family — Ola Belle Reed & Family

Ola Belle. The original queen of bluegrass singer/songwriter banjo players. She wrote about half of the classics on this album, including “I’ve Endured,” which you probably know from Tim O’Brien’s version. She comes right out and sings “Born in the mountains, 50 years ago” — her age at the time of this recording in ’76 — while most of the cover versions get slippery with “many years ago.” The only quandary I had in including this record on my list of favorite bluegrass albums by women is that I’m rarely able to listen past the brilliance of track four, which happens to be the one song Ola Belle’s son, David, sings solo while accompanying himself on the autoharp. His version of “Lamplighting Time in the Valley” (an old Vagabonds song) is one of those magic tracks that hits you from another dimension and must be listened to on repeat, but since Ola Belle created her son, I’m going to give her the points for that one, too. — Kristin Andreassen

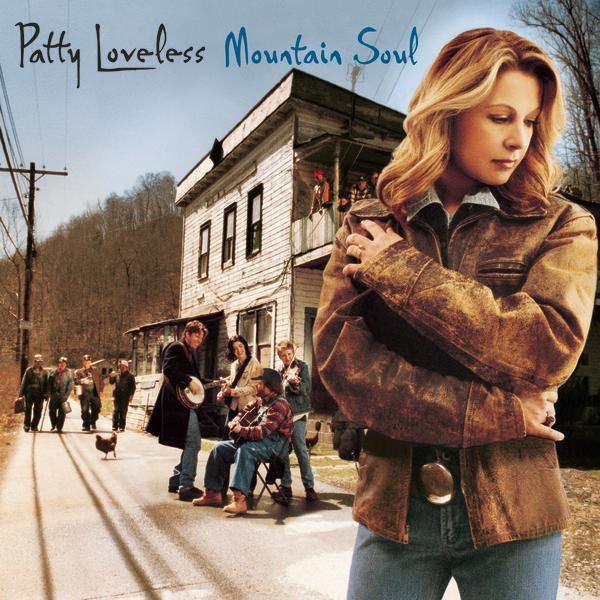

Patty Loveless — Mountain Soul

“Mountain soul” is a common attribute associated with Patty Loveless’s stunning voice, long before she decided to pay homage to her eastern Kentucky heritage with an album by the same title. Her 2001 bluegrass project might be the most authentic of the “country-star-makes-bluegrass-album” endeavors that we have seen. Joined by bluegrass veterans — including Earl Scruggs, Gene Wooten, Clarence “Tater” Tate, and others — Patty also featured some all-star talent from the likes of Ricky Skaggs, Travis Tritt, and Jon Randall for some powerful collaborations. Without question, though, the album’s pinnacle performance is the now-classic rendition of Darrell Scott’s “You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive” — six minutes of nothing but Patty’s signature “mountain soul” sound. — Daniel Mullins

Rayna Gellert — Ways of the World

So Rayna will see this list, raise one eyebrow, and say, “Did I make a bluegrass album?” … because she plays old-time music, you know. If you’re still unsure of the difference, let Ways of the World be a guidepost. Groovy as a giant’s corduroy pant leg, this music needs a fiddle chop like a hole in the knee. But an album of mostly string band instrumentals, including a blessedly reincarnated version of the 100 percent bluegrass-certified “Arkansas Traveler,” is surely a close cousin. When Ways came out in 2000, it was a big moment for those of us who were just coming up through the cracks between folk revivals. A little younger than the hippies and a little older than the yet-to-be hipsters, there weren’t so many of us kids on the scene then. Ways came to me as a gift, and there was a picture in the liner notes of Rayna getting her head shaved. So, of course, we met, and eventually we had a band called Uncle Earl. — Kristin Andreassen

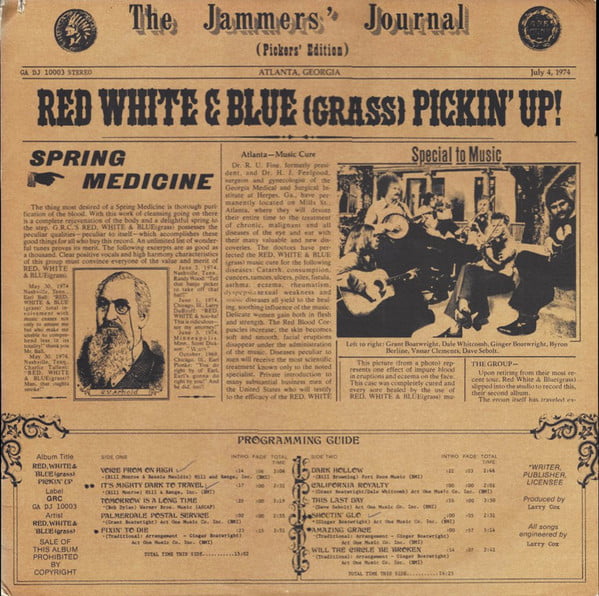

Red White and Blue(grass) — Pickin’ Up

This is the second LP by this early supergroup led by Ginger and Grant Boatwright. Although the album includes just one of Ginger’s original songs, her expressive singing is front and center on most of the tracks. Outstanding instrumental work by Grant on guitar, Dale Whitcomb on banjo, and Byron Berline and Vassar Clements on fiddles make this some of the best ‘70’s bluegrass ever recorded. The repertory is beautifully varied, too, with Ginger’s brilliant renditions of a couple of Bill Monroe classics, original instrumentals by members of the band, Bob Dylan’s “Tomorrow Is a Long Time,” and such diverse traditionals as “Fixin’ to Die” and “Amazing Grace.” — Greg Reish

Rhiannon Giddens — Freedom Highway

While it’s merely bluegrass-adjacent with its old-time, soul, and folk tendencies, this album should be on a list of the top 50 albums by women, regardless of genre. It’s just that good. And just that important. From her early days in the Carolina Chocolate Drops to her current standing as a MacArthur Fellow, Rhiannon Giddens has shown us, time and again, that she ain’t messing around. She is a student of history and an advocate for justice, folding both of those duties together in her music which uses our past to gauge our present. To that end, on Freedom Highway, she gives voice to slaves and other victims of racial violence who dare not speak for themselves, but whose stories must be heard by all courageous and conscious enough to listen. And she stands firm in the roots from which bluegrass grew. — Kelly McCartney

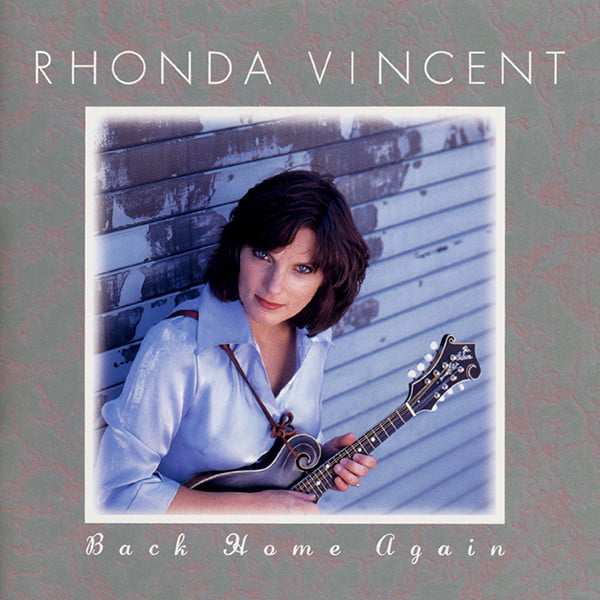

Rhonda Vincent — Back Home Again

Following a mid-90s foray into commercial country music, Rhonda Vincent had been back in bluegrass for a few years already before releasing her Rounder debut. But signing with the industry-leading label spurred her to a deliberative process that, combined with some of the best singing you’ll ever hear, makes the album a bona fide classic. She recorded two dozen tracks, then listened to what they told her when it came to making her final selections. Back Home Again combines kick-ass, hard-edged bluegrass played by a large and varied all-star cast with heart-wrenching country ballads sung with immaculate yet gripping harmonies, mostly from her brother Darrin with an occasional assist from their father and a couple of others. Nevertheless, the dominant term in the equation is Rhonda’s own singing — not to mention her hand as co-(and arguably lead) producer. The whole thing is polished to a high, high gloss, but it’s compelling as all get-out. — Jon Weisberger

Rhonda Vincent — The Storm Still Rages

At the turn of the century, Rhonda Vincent made a triumphant return to bluegrass music following several years of an under-appreciated country career. Back Home Again resulted in her being crowned the “Queen of Bluegrass,” and 2001’s The Storm Still Rages only enforced the moniker. Perfectly toeing the line between hard-driving traditional bluegrass and smooth acoustic sensitivity, the album includes such Rhonda Vincent classics as “I’m Not Over You,” “Bluegrass Express,” “You Don’t Love God If You Don’t Love Your Neighbor,” and “Is the Grass Any Bluer.” That year also marked Rhonda Vincent & the Rage’s Entertainer of the Year award from the IBMA, making her one of only two female band leaders to bring home the IBMA’s top honor (the other is Alison Krauss), and resulted in her second (of a record eight) IBMA Female Vocalist of the Year awards. The authority with which she sings and plays every note leaves those who want to throw about the “pretty good for a girl” caveat looking foolish. Rhonda is continually expanding the levels of professionalism in bluegrass music, and her ability to raise expectations (not just for women, but for the entire industry) is why she is one of the genre’s premiere figures. The Storm Still Rages is one of the queen’s crowning achievements. — Daniel Mullins

Rose Maddox — Rose Maddox Sings Bluegrass

Released in 1962, this album has the distinction of being the first in the bluegrass field by a female vocalist. I first heard it in about 1974, and while I couldn’t really accept her voice as a bluegrass instrument (her big brassy vibrato sure doesn’t sound like the Stanley Brothers!), I kept going back to it for the sheer fun, the energy of the music, and for the repertoire. It’s got a fine back-up band, featuring Don Reno on banjo, Tommy Jackson on fiddle, and Ronnie Stoneman and Bill Monroe splitting the mandolin chores. — Laurie Lewis

Sara Watkins — Sara Watkins

No, it’s not the most traditional bluegrass album ever recorded, but coming out of Nickel Creek’s more progressive latter days, Sara Watkins’ debut solo record illustrated that she still had at least one foot planted firmly in tradition. But who’s counting? These originals got me through more than one heartbreak and the covers — of Norman Blake, John Hartford, Tom Waits, and Jimmie Rodgers — confirm the respect for the music’s past that you can feel as you listen. Make no mistake, though, Sara Watkins is looking toward roots music’s future; her following solo albums and her work with I’m With Her are blazing a trail I’m excited to follow. — Justin Hiltner

Sierra Hull — Weighted Mind

I think I saw Sierra perform for the first time with her band Highway 111 when I was 17 years old. I was simultaneously inspired — and infuriated — by the fact that someone my age could have so much creativity, such great touch and tone, and such ridiculous chops. Through the years, as we’ve both grown up, the inspiration has only increased and the infuriation is now much more … constructive. Weighted Mind has been hailed as a coming-of-age record for Sierra, but I think that categorization is far too simplistic. When I listen to this record, I do hear maturity, but more prominently, I hear individuality, vulnerability, confidence, transcendence, and infuriating, ridiculous chops. — Justin Hiltner

Skyline — Fire of Grace

This is a weird album, but it was one of the first weird bluegrass albums with a woman fronting the operation. And, yes, Tony Trischka’s name is sort of up front in this band, but it was Dede Wyland’s singing and guitar playing that really stood out. — Megan Lynch

Uncle Earl — Waterloo, Tennessee

Any list of great female albums anywhere in this realm would be incomplete without an entry from the “Bangles of Bluegrass” — Uncle Earl. And their 2007 release, Waterloo, Tennessee, proves why. Packed with 16 old-time tunes, the set weaves the ladies’ vocals harmonies and instrumental chops into an irresistible musical tapestry that is both contemporary and classic. (Rumor has it, the G’earls — KC Groves, Abigail Washburn, Rayna Gellert, and Kristin Andreassen — may even be readying some new material.) — Kelly McCartney

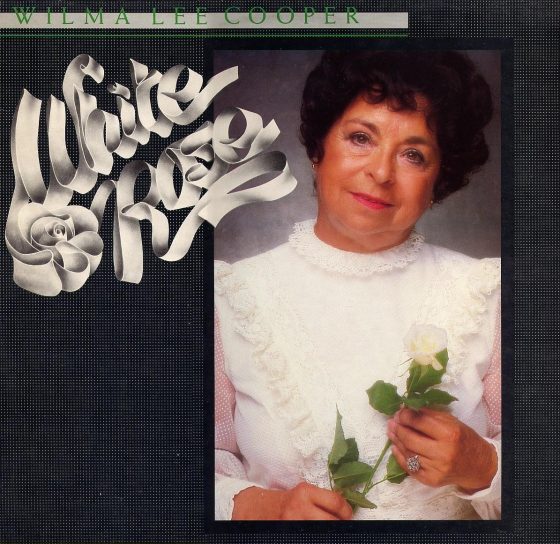

Wilma Lee Cooper — White Rose

After many famous years of singing old-time country music with her husband Stoney, Wilma Lee Cooper released a string of solo albums that veered more and more toward bluegrass following Stoney’s death in 1977. Recorded for Leather Records, which released A Daisy a Day (Wilma Lee’s solo debut), White Rose was recorded in 1981 but wasn’t released until Rebel issued it in 1984. This is pure bluegrass, with Cooper accompanied by some of the best Nashville pickers who also played with her on the road and at the Opry — Marty Lanham on banjo, “Tater” Tate on fiddle, and the brilliant Gene Wooten on dobro. — Greg Reish