Maybe it’s true in life, but it’s certainly true in writing about music that the longer you do it, the more often you hear echoes of the past — not only in the music itself, but in artists’ attitudes and, especially, in their stories. Hearing Old Crow Medicine Show’s Ketch Secor recount the odyssey that preceded the band’s settling in Nashville, it’s easy to be reminded of the contintent-spanning journey taken by Western swing ensemble Asleep at the Wheel some 30 years earlier. Like AATW, who eventually were embraced by all but the most benighted purveyors of authenticity — and with whom they recorded a blistering “Tiger Rag” in 2015 — Old Crow have made their way into the heart of hillbilly music’s most cherished institutions, signified by their 2013 induction into the Grand Ole Opry cast.

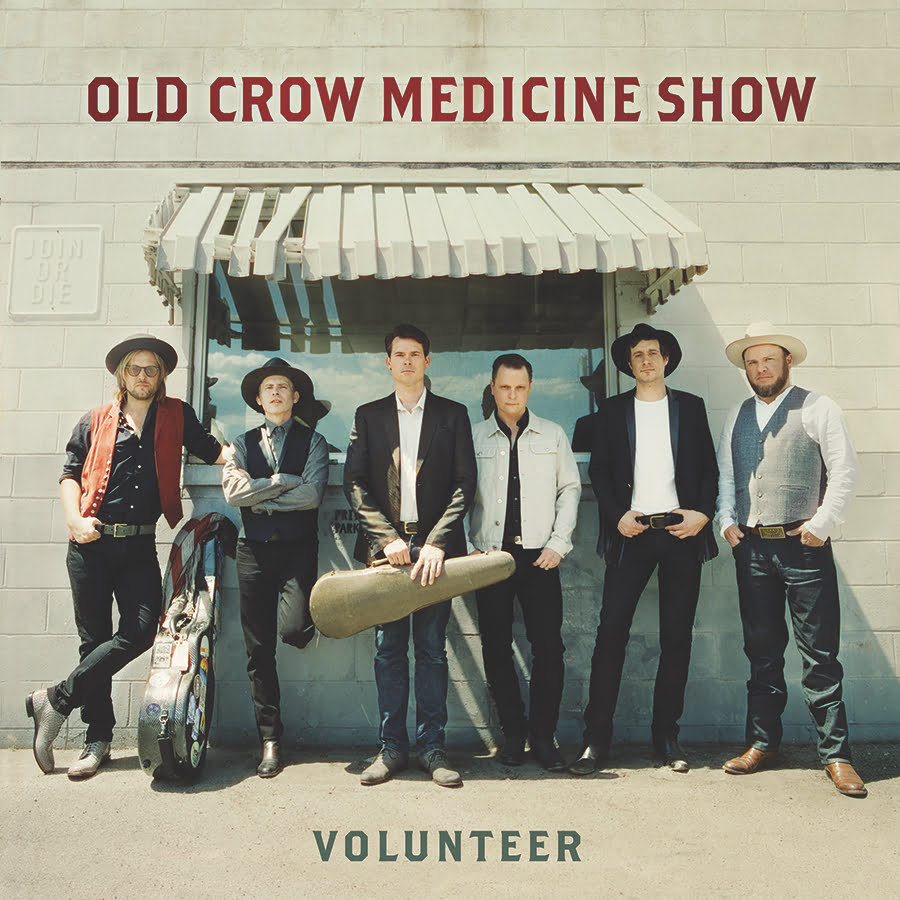

Yet the group’s ascension to Opry membership was hardly predictable, much less preordained. Old Crow’s stature in the country music world has been built on a determination to make their own sound that’s every bit as strong as their allegiance to the broad swath of hillbilly music music that forms its foundation. When Marty Stuart invited them to join the Opry, he mentioned an early description of the radio barn dance as a “good-natured riot,” and it’s a description that obviously applies to the band’s shows, too — a simultaneous looking back and looking forward that has made legit fans out of the likes of bluegrass Hall of Famer Del McCoury. With Volunteer marking the group’s 20th anniversary, it seemed like a good time to look back at how they got from there to here.

The press release mentions this is the 20th anniversary of the band.

That’s no joke, brother.

Does the band have a hard start date — a day you could point to and say, “This is the day the band was formed”?

Well, the band left — that’s the day the wheels turned, and we left our home — in October of 1998, because grape season was over, and we had money. We had picked enough, and raised enough, and washed enough dishes, and cleaned enough attics, and played enough nursing homes, and bought enough cartons of cigarettes to get across the border in style.

I was thinking about this because the occasion for this interview is the release of a new record and, 20 years ago, the record industry and the music industry looked a lot different than it does now. And you guys have become what you are during this period of tremendous change and turmoil.

For example, when we crossed that border and finally got waved through into Canada in the fall of 1998, one of the things we had packed was our boombox, so that we could dub our tapes. Because this band sold cassettes. In 1998, this band sold cassettes on the street corner for $10 — Canadian. That was crazy. We were selling them, too. Our tape was flying out of the box — we had a shoebox full.

Why was that?

Well, it was not the quality of the tape. The tape wasn’t very good. We recorded it with one microphone hung from the ceiling, on a four-track recorder. It sounded really, really shitty — low-fi, low quality. That tape was called Trans:Mission. It was the time to dream, with your body, the things that you wanted to have happen. It was the time to read Bound for Glory by Woody Guthrie and think, “I’m going to get on that boxcar, too, goddammit; I’m going to hobo. I’m going to thumb it, I’m going to flag the diesel down. I’m gonna go West.” A good time in life to take that risk, and drop out. Isn’t that what it’s all about? Isn’t that where all of the magic lies, in that moment of deciding that you’d rather wear a mask — and pick a really great one?

So you made your way to Nashville …

That happened three or four years later. Now, I had already been to Nashville before I got to Ottawa. I had been here with another band in 1997, and played on the street corner here. I was gonna busk! I’ve been busking Nashville for like 23 years, or something stupid like that.

What’s the value of busking? I mean, aside from the financial.

Well, we can’t all play like Del McCoury, or anyone in that band — particularly when we’re kids. But we had the passion. It’s the same passion. I was never gonna get as good at playing the fiddle as Jason Carter, but I had the same drive to play as hard as Jason plays. And I couldn’t get onto a stage anywhere because … well, one, I was drunk. I had taken this old-time loyalty oath that made me fiercely pro-old-time and anti-bluegrass, so I didn’t play well with others. I was rabble-rousing. And also, I sucked. So where was I gonna go, with all of that energy and drive, but none of that finesse? And I was somewhat unapproachable. I might have smelled bad. I might have had blood on my shirt, or on my mouth. That was part of the mask I wore, was unapproachability.

Being in Tennessee seems to be important to the band, at this point. Is that a fair statement?

Yeah. I think, as soon as we got to Tennessee, it got a lot more legit.

In what way?

It got legit because it got more focused on the idea that, all right, this band is the soap box. In the chapter previous to our move to Nashville as Old Crow — which is the chapter that runs from about 1999 to about 2000-and-a-half — in that chapter, we were probably as interested in farming and making whiskey and planting by the lunar signs as we were about playing live shows. And that was where learning about early hillbilly and country music was as much an engagement with the landscape of the music as it was with the actual performance of the music. When it got to Nashville, then it became about doing that in Nashville, which had a different musical landscape.

So, in our journeying, we start with the quixotic journey, which is the fire, the odyssey. And then we end up in this sort of hillbilly monastery up in east Tennessee and west North Carolina. And then we come to Nashville, and we end up in this crack house kind of mentality of revolving doors of freaky people, motel rooms, and rent money going out and booze coming in, and songs, and percolation, and Del McCoury, and the road. The beginnings of the way the road would look. It became more vocational and less about kind of artistic presence and disturbance. As buskers, we were as much protesters as we were entertainers.

You guys still feel that way?

Yeah.

How does it express itself? Musically?

Oh, there’s a ferocity to what we do, and an intensity. I mean, I’m feeling it right now, which is why I’m jacked up. But I’m jacked up always. I’m always jacked up, when I talk about the fiddle, and when I talk about John Hartford and Del McCoury. I’m always jacked up because that stuff’s just so powerful.

When I hear “volunteer,” especially in a music-related setting, I think of the Volunteer State — Tennessee. Is the title a reflection, in part or in whole, of the environment in which you’re in now? Or does it have some other significance?

What I think it means is that it hearkens to the pack mentality of our youth. The band really took this oath, this pledge, and we all volunteered to risk our lives, to sacrifice personal identities, personal goals, for collectivity. To be very much a band. The way that we lived together — it’s like we had all signed up, that we would do it come hell or high water. And it turned out it was both.

There’s an audience connected to old-time and bluegrass and country music — all the variety that gets presented on the Opry — by virtue of where they were born, who they grew up with, and the community they live in. And then there are whole other audiences who are drawn by maybe musical affinity, or some kind of cultural signifying. One of the features of our world in the last few years has been that the differences between all these people has become more apparent and the edges become a lot sharper. You guys are also heading for your fifth anniversary as Opry cast members. You play the Opry, which is still kind of a focal point for one community, and then you go out and tour and play for all these other audiences. It feels to me like that’s reflected in some way in this record. Is that true?

When we play the Opry, we’re mostly playing for tourists. But we’re also playing in a kind of center of all of hillbillydom. And when we play the “Wabash Cannonball” on the Grand Ole Opry, we sound more like the Woody Guthrie role than we do the Montgomery Gentry role, or even the Roy Acuff role. Roy is kind of the same as Woody. He’s a good example because, though politically, he’s certainly on the right — he’s from East Tennessee, he’s a Republican, he’s a conservative dude, he wants to shut down the Opry because he doesn’t want to share the same locale as the peep shows and the drug dealers, so he advocates moving it out. But he’s singing music that makes you want to desegregate a school, because that’s the power of the “Great Speckle Bird,” that’s the power of the “Wabash Cannonball.” They’re actually very front-line songs, really excited, rabble-rousing kind of proletariat sounds.

That’s the thing about country music: The people, en masse, who believe in the power of folk music, just by nature of having an underserved class being championed by a music — that’s a very expansive concept, one that can’t be pigeonholed in any particular political realm. We played the Budweiser stage last week, and most people were about 25 years old or younger. We’ll play gigs this summer where everybody’s 25 or older, 50 or older — we’ll see crowds from Delaware to Red Rocks and everything in between. We’ll play in Oklahoma to drunk leftists, and we’ll play in New York City to conservative lawyers. And everywhere we go, we will allow people to step into a world that has no political affiliation. That is the world of Old Crow, the entertainer. And the Old Crow who’s an entertainer, I always think of him as this top hat-wearing bartender that’s serving it up to the people, no matter what the color of the skin is, or who they voted for. Because the Old Crow, he doesn’t vote. He just pours.

So what’s the connection between Old Crow, the entertainer, and that volunteer collective that stepped up and took its oath? What you described as the fundamental nature of the band — of you coming together and making this choice to pursue something — seems to imply a certain kind of purposiveness that goes beyond being an entertainer.

The political party here is, live music is better. The revival tent, or the voting booth, or the campaign rally is one in which you believe that live music has the power to change the world. I like records fine, but we’re a live band. What we do is play the music that we play in the moment that you’re hearing it. If you’re on your phone getting a message from a friend, you missed it. Sorry, dude. If you go to the beer line, that’s cool, we’re going to keep doing it. You don’t have to hang on every word. But this is our tent here. It’s the live music hour. That’s what we do.

We’re having this conversation, in part, because you made a record. So if live music is where it’s at, and that’s one of the changes in the music industry over those 20 years, and that records no longer occupy the same position in the music world, what are you wanting to do with this record?

Put another ring in the tree upon which this Old Crow has been precariously perched these 20 years. It’s just another ring in the tree, another notch in the belt.

Photo credit: Danny Clinch