What do you get when you cross a bunch of roots-minded female singers with a bunch of bluegrass-adjacent male musicians? Why Ladies & Gentlemen, of course the new release from the Infamous Stringdusters which features appearances by Joan Osborne, Lee Ann Womack, Mary-Chapin Carpenter, Abigail Washburn, and eight more of the finest voices roots music has to offer. It's the sixth record in nine years for the band — which is comprised of co-founders Chris Pandolfi (banjo) and Andy Hall (dobro), along with Andy Falco (guitar), Jeremy Garrett (fiddle), and Travis Book (bass) — and it showcases why the Stringdusters are considered one of the most innovative groups currently on the circuit.

First off, kudos on some great guests. [Joan] Osborne and [Lee Ann] Womack are two of my all-time favorite voices. So, did you guys just put a bunch of singers' names on a dart board and start throwing? How'd you figure out who you wanted?

Chris Pandolfi: The concept for this thing was two-fold: On the one hand, we wanted to do something different, as far as an album goes, just to mix it up. But a big part of it was also that we had made a lot of great friends along the way and we thought, “Who could we utilize, in terms of special guests?” And this concept evolved out of that — “What if we call on some of these awesome lady singers that we've met over the years?”

As the process started, the list was mainly comprised of people who were more in our community, in our musical scene. But, then, of course, some of those names were not, necessarily, people that we knew before the advent of this project — like Joan Osborne. The list was a combination of the two and, as the material evolved and we were getting a feel for the aesthetic of these different songs, we just did the best we could. Once the list was close to what we thought it would be and we got some confirmations from people, we — along with our producer — just did our best to match up what songs we thought would be best for each lady.

To me, that's one of the awesome successes of this album: It really uses these artists, I think, in a context that works for them. Look at the Joss Stone track or the Lee Ann Womack track … or Celia Woodsmith, who had the perfect voice for that song. All the ladies, in their own ways, brought their thing to the project and I think, in the process, they helped us take these songs and make them something that we couldn't have necessarily done on our own. They helped us make the most of all these unique and different sounds and styles that they have. It really came together that way. Certain people weren't able to do it, and the list filled out from there. But where we ended up, as far as the guests and what songs they were on, I think that's one of the cool successes of the album. The song “Have a Little Faith” was actually written for Joss Stone, with her in mind. I know that.

I was going to ask … considering that the span does run from Joss Stone to Sarah Jarosz, which came first — the singers or the songs? Did you write for specific voices or was that the only one?

Andy Hall: Yes, I believe so. Aside from that, we all write individually or co-write or whatever and bring songs to the band. So we all had songs, individually, that we were ready to bring to the next project. But I think that was the only one that was written for the singer. In other instances, say for Aoife O'Donovan, hearing that song “Run to Heaven,” it sort of reminded us of Crooked Still, just the way that sounded. In that instance, that became clear that would work that way. Each song just triggered a little something … an idea. That was one of the fun, creative parts — who would sound good on what song.

So how'd you figure out that Joss likes a little bluegrass in her soul?

AH: [Laughs] Andy Falco was hired to play in her band for a Rock in Rio festival a number of years ago. That's how that connection came about. Our connection with Joss was one of the things that inspired this record because Joss came to the States, and we opened up for her in Kansas City. She wanted to do a video of us and her playing together, during the day. She sang our song “Fork in the Road” with us backing her up for this video project she was doing, and it just sounded so cool. That was one of the sparks for this project. But that's also how that connection came about.

Interesting. Who was the first to say yes? And who was the biggest long-shot you can't believe you landed?

CP: Hmmm … Who was the first to say yes?

AH: The first person who recorded with us was, I believe, Jen Hartswick who didn't sing, but played trumpet on a number of songs. Then Mary-Chapin Carpenter was the first vocalist to put her track down. She was in Nashville while we were tracking. But, as far as asking, I don't remember.

How free were the reins when it came time to let them do their thing? Was it, “Have at it, gals!”

CP: Our producer was on hand for every session, I think, except for one or two. He did a really great job with this project — Chris Goldsmith — just in terms of staying true to his vision, which a lot of it was sonic, and he got a really cool, consistent sound across the record, although there is a real variety of styles there. I think that vision extended into how these songs would sound best. But, then again, there were cases — Joss is a great example … that track, by design, was made to let her do her thing which is to cut loose and almost improvise a lot of the phrasing. In cases where that would make the music come to life, that's what happened. In other cases, probably Goldsmith had a clearer vision of how it was supposed to sound. To some extent, every song was about letting these ladies do their thing.

The Sara Watkins track jumps to mind. She has such a compelling vocal on there and it's all because she does her thing. There's a moment where she really goes for it, and she's such an awesome singer and performer that the idea of getting her to do her thing, that's the whole point. So, to some extent, I think that was going on with everyone.

Obviously, all the guest vocalists aren't on the road with you, so how are you touring this record?

AH: We have Nicki Bluhm on the road with us for this whole tour and she is really helping. She's singing a lot of the Ladies & Gentleman songs that we do. Sometimes we'll do a few just on our own, but Nicki's on every show for the whole Spring tour so she's singing a lot of it. We also had Della Mae opening for it on a bunch of it, and Celia Woodsmith would come up and sing her song.

It's amazing how you cross paths with musicians on the road and that's, initially, how we made a lot of these contacts. We ran into Aoife O'Donovan — she was in L.A. when we were there recently, so she came and sang with us, and did a Jam in the Van session with us. We've designed part of the tour to have female bands supporting us, so we have Paper Bird coming out to open some shows and, hopefully, they're going to be able to help share some of the vocal duties. We have a lot of guests, but Nicki is anchoring all that.

More broadly speaking, you guys are very invested in being innovators within “bluegrass.” That's often a very subtle thing, though, right? So break it down … what are some of the things you guys do to open it up a bit and set yourselves apart while still honoring the traditions?

CP: One big thing that we're really focused on, consciously, is playing our own original music. The process of crafting original music is the thing that, simultaneously, helps us develop our sound as a band. We have a lot of co-writing going on, but mostly we arrange the music together. And we just try to figure out new ways to make all these instruments go together and distill all the different styles and influences into one sound that makes sense. We're pretty conscious about that.

We're really conscious about our live show. We're pretty committed to making the live experience really different every night. Of course, we're not the first band to ever do that, but we just try really hard to do our own version of that. And our fan base has come to expect a lot of variation and innovation, as far as on a night-to-night basis. They expect to see something different, and we're playing almost three hours a night, so we have to mix it up for our own sakes, too. Those are two big ones: playing our own stuff and focusing on having that live show be something that is really predicated on being different every night.

AH: One thing, specifically, that I know we've worked on a lot in the past few years is that we don't have a mandolin, which a lot of bluegrass-type bands have. The mandolin is a key rhythmic thing. Since we don't have that, we've had to get really creative with how we play rhythm and play rhythms that are not, say, bluegrass. Like on the Ladies & Gentlemen record, there are a lot of songs that don't have a traditional bluegrass beat. We've consciously spent a lot of time developing unique ways to play our instruments that you wouldn't necessarily expect or hear in other string band contexts. Myself being a dobro player, I take a lot of the rhythmic responsibilities, which is not a common thing. Not having a mandolin, we've had to get somewhat innovative with how we create rhythm and play grooves that aren't necessarily bluegrass. To me, that's something unique that we do.

It seems like there has to be a lot of trust between the band and the fans. You have to trust that they're going to follow you wherever you go, musically. And they have to trust that you're not going to do some crazy, way out of left field thing. Do you ever worry about splitting the difference in such a way that you isolate them … or any part of them?

AH: Well, yeah. The scene of traditional bluegrass and, say, the broader music scene that we're playing more in now, there is quite a difference there. We've chosen to be part of a music scene that is broader, where we play in festivals that are not just bluegrass festivals. I think, in that context, it's not quite as strange to have music that is slightly more creative, record to record. A lot of the fans we're appealing to are a little more used to that. But this is the first time we've ever done a record like this that is a very different, specific vision. Sure, you certainly wonder, “What are people going to think?” [Laughs]

CP: And we have, over the course of our career, definitely alienated people. That's part of the natural course of things. What we do is our thing. We decide where the music goes. That's one of the cool upsides of not being in what most people would perceive as a more popular style of music: You're not really beholden to any record label or anything like that. In the grassroots scene, there is some idea that your fans are going to follow you wherever you will go. Obviously, there's an extreme there and there are anomalies to that rule. But, for the most part, we're lucky: We have these great fans who want to check out all the different voices.

I have a side project that involves electronic elements and it's clearly not for the hardcore bluegrass people of the world. But there are plenty of people in our fan base who, though they don't listen to anything like that, they are excited for that to be their introduction to this musical world. I think that's a good glimpse into the way they think. They're like, “We love this band. We want to see what they're going to do. If this particular thing is not my cup of tea, then there's always going to be another album that comes out.” I think they are getting used to the fact that there are a lot of variations between projects and between songs and the live show, so it's almost part of the whole thing. So, for me, I'm not ever too worried that they're not going to dig it. As long as we make music that we believe in, I think our fans will get behind it.

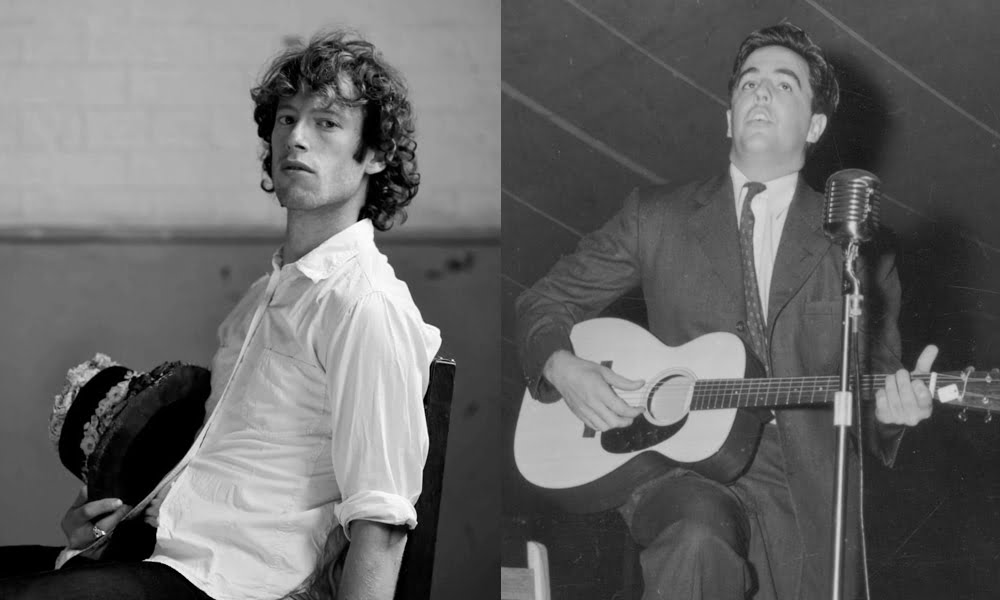

Photo credit: McCormick Photos & Design, LLC