Growing up, Martha Scanlan says she equated music with “belonging and family and home.” The Montana-based folk singer-songwriter has woven those elements into her fourth album, The River and the Light, but, for Scanlan, home doesn’t exactly signify hearthfire. There’s a wilderness brooding about the album, as she moves throughout the landscapes that shaped her. She’s found her place in the natural world as much as those vistas have found their place in her.

Longtime friend and creative partner Jon Neufeld produced The River and the Light, continuing a collaboration that spans back to her 2011 album, Tongue River Stories. The two blended an array of brooding and beautiful timbres — with fiddle and accordion from Dirk Powell — that speak to those natural landscapes: The expansive skies and pressing quiet of Montana (“Only a River/True Eyed Angel”), the weathered mountainscapes and ancient tones of Appalachia (“West Virginia Rain”), and even, at times, the lush forestry and friendship she’s found in Oregon, where they recorded the LP.

Scanlan herself has described The River and the Light as a journey, which makes sense when you consider that journeys are as much about leaving as they are arriving home. She joined Neufeld on the phone during this interview with the Bluegrass Situation.

Looking back to Tongue River Stories, elements of place and belonging and journeys have always informed your songs. If you look at The River and the Light as a new chapter, what have you learned in that interim?

Martha: There’s this old cowboy saying that just jumped into my mind: “A horse will make a liar out of you.” As soon as you say a horse is one way, like, “This horse never bucks,” it’s going to buck you off. As soon as I say that a song is about something, it’ll end up being about something else. One thing that was interesting in terms of Tongue River Stories, which was such a collaboration with the landscape itself, is we were recording songs outside and the sound between the notes was the actual landscape. This record feels like its own landscape.

You both seem quite interested in atmosphere. I couldn’t get over the timbres on “Too Late.” How did you build those colors into that song?

Jon: Well, I know we got Dirk Powell’s fiddle part. He wasn’t able to make it to the studio, but he sent us a rough mix — he played some fiddle and accordion parts in that. I added some baritone guitar and acoustic guitar. There may have even been omnichord on that one. I ended up sneaking the omnichord on quite a few songs. And then near the end, I was thinking we needed something more, and Martha was back in Montana already, and she sent me… How did you even record that?

Martha: I had this really lame zoom video recorder that I got eight years ago or something, but it has a pretty good microphone. I recorded some brushes, like playing brushes on tambourine, and some harmony parts.

Jon: [Laughs] So she sent that. And I added that to it.

Martha: I think that song is probably the most layered one on the record. Or the most that had an afterwards. What was interesting to me about Jon’s production, I don’t know another musician that’s so in the moment and improvisational when we’re playing live or in the studio or anything. It’s fun because to watch him putting on different layers or overdubbing something because it’s that improvisational. It’s not contrived, it’s not overworked; it tends to feel really alive.

Dick Powell has said about you, “Martha feels the natural world…to such an extent that the stories transcend themselves.” How do you view your relationship with natural space?

Martha: I think there’s an openness, for me, about working and living so close to landscape that’s very much like music. I lived on this small ranch for seven or eight years in southeastern Montana. Doing Tongue River Stories, we recorded most of that outside and we could do that because it’s that quiet — there aren’t cars or planes overhead. To me, writing is more about listening than it is about planning or thinking. I’ve never been good about like, “I’m going to write a song about this.”

It unfolds on its own.

Martha: Yeah and seeing what shows up. As far as a theme in writing and in the music, I think that there was an element of this record that was an exploration of rivers, or different currents that run through and wind together. For both Jon and I, that’s something that occurred early on when we were passing ideas back and forth.

Are you thinking specifically about a certain river or more metaphorically about them?

Martha: Kind of both. I think I’ve always been fascinated with rivers and I’m around rivers a lot.

Jon: Yeah, I remember that back and forth. The theme of rivers was on the last track, “Revival.” I was like, I think it’d be really cool if you were going along a river and this thing pops up. All of a sudden, there’s an acoustic guitar solo for no reason; there’s no acoustic guitar until then. Just the way you go down a river and something appears and is gone. That was a very real theme, like visualizing the river and making a sonic imprint of that.

What keeps this partnership between the two of you so worthwhile in your minds?

Martha: It’s a hard question to answer because it feels really easy and congruent. What would you say, Jon?

Jon: I feel like in the first five seconds you can tell if you’re going to jive with somebody or not; I think it’s especially so with artists and musicians. When we first started playing together, it’s an obvious feeling. It’s obviously not wrong.

Right. You wouldn’t have worked together so many times if it weren’t working.

Martha: Something I really appreciate about working with Jon is there’s this constant sense of improvisation on stage and in the studio. Everything is very alive. We don’t practice a lot. [Laughs] We usually show up on tour and the first time we play together is, like, a radio show or at the sound check. But it keeps things very fresh and alive, I think.

Speaking of being in the moment, I read that “Brother Was Dying” was done in one take.

Jon: That’s probably the truth about most of the album.

Martha: That one, I had just finished putting the words together — I had written most of it, but it was still in this place where I wasn’t sure how it would all stitch together — and we went in and recorded it. I hadn’t sung it as a complete song; that was the first time we’d really played it.

What does your writing process look like nowadays?

Martha: For this record, I had started playing electric guitar; I was pretty psyched about that. It’s a really different animal: It’s a wash of sound, the physicality of it is really different, there’s a lot more fluidity in it. So I think messing around with that influenced some of the writing. It’s still to me such a process of discovery, writing songs. Some things just kind of show up, and then it becomes an inquiry, and sometimes that process continues for years after I write the songs. I feel like I go out and interact with whoever is listening to it and come back changed. I really enjoy that part of it. I think my last record, which Jon also produced, was so much about the current that moves through things, and this record felt even more whittled to the current that’s flowing through.

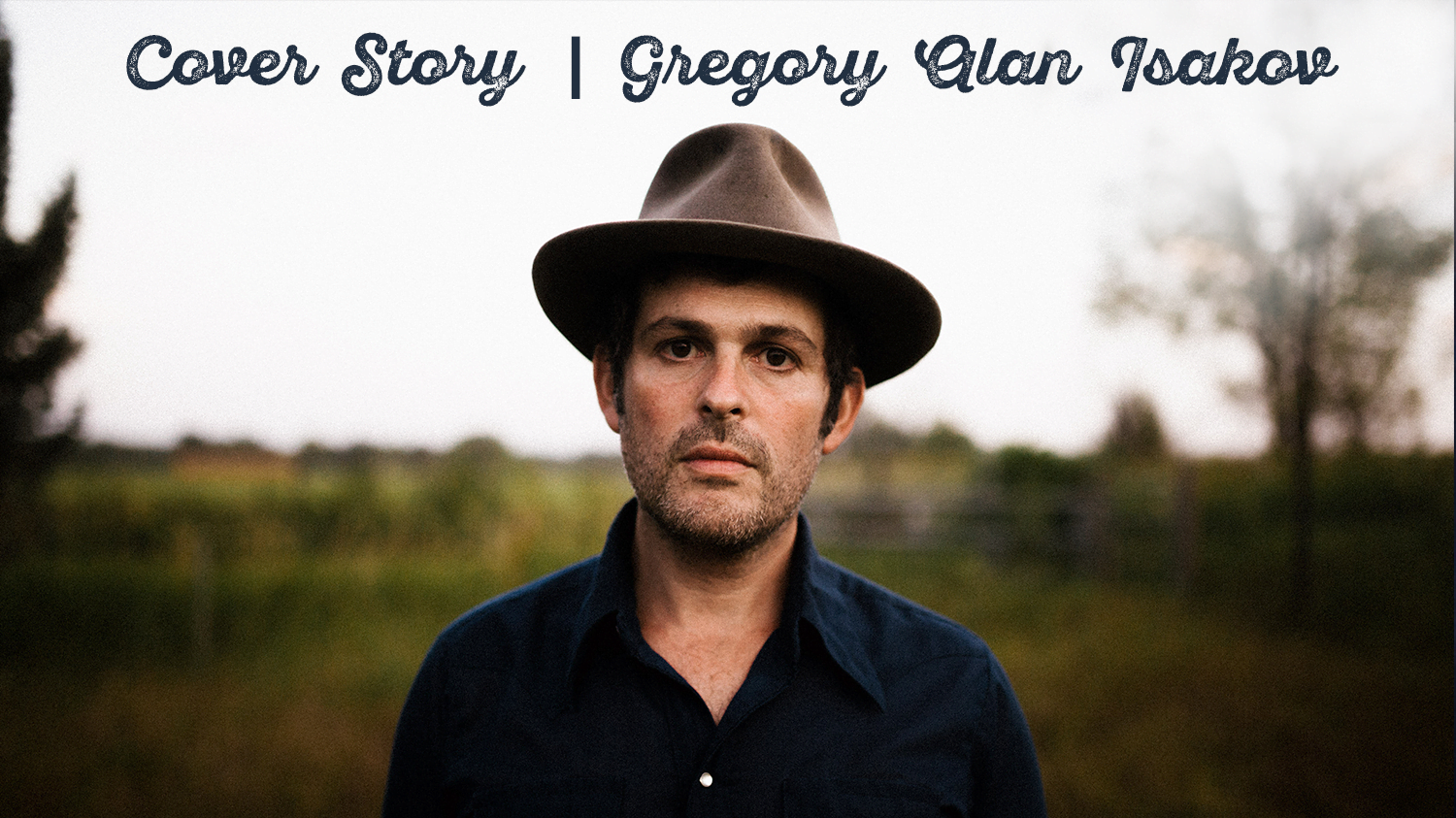

Photo credit: Yogesh Simpson