In early February, the Empty Bottle Stringband made their debut at the Carter Family Fold in Hiltons, Virginia, a hallowed ground for lovers of old-time and country music. A quartet of old-time musicians based in Johnson City, Tennessee, the Empty Bottle Stringband specializes in the lively, toe-tapping fiddle tunes that fill the floor with dancers at the Carter Fold, and the band is familiar with the musical family who gave the venue its namesake. When Tyler Hughes takes up the autoharp and introduces the Carter Family song, “There’s No Hiding Place Down Here,” the sounding rhythm is closely kin to the style of Mother Maybelle Carter, a living example of the sound that brought Southwest Virginia to the world’s musical attention. Hughes’s performance carries other ties to the cultural ground he’s standing on: in the clear, true tone of his singing, the stories that enrich the music, and the down-home humor that has brought laughter from generations of careworn audiences.

As a solo performer and member of the Empty Bottle Stringband, Hughes has represented Appalachian culture on stages across the eastern United States since his teenage years. Now in his mid-20s, he continues to live, teach banjo, and organize cultural arts projects in his home community of Big Stone Gap, Virginia. Hughes is a graduate of the Old-Time, Bluegrass, and Country Music Studies program at East Tennessee State University and, during his time as a student, he performed extensively with the ETSU Old-Time Pride Band. Whether he is attending a board meeting for a community foundation, calling a square dance, or showing a local kid their first chords on the banjo, there’s a reverence of heritage evident in all of his work. The ties to Hughes's Appalachian heritage are collective — traditions of music and dance which work best when a group will put them to use, not admiring them from a distance, but participating in the present.

Tyler, tell me where you grew up, some of your family’s history there, and how you started to play old-time music.

I grew up in Big Stone Gap, in Southwest Virginia. I grew up in town, but on top of a mountain; we have a really beautiful view of Powell Valley from our front porch. I grew up in the mountains, playing in the woods, and I had some interest in music as a kid, but later in my teen years, I took up music more seriously. My family’s been here for several generations now, and my mom and dad were both raised here in Big Stone. My dad was raised in town and my mom was raised outside of town in Powell Valley in a little holler called Cracker’s Neck, which sounds like a really magical place and it was. My mamaw and papaw lived in Cracker’s Neck, and my papaw still lives there. Both of them were avid country music fans — and so is my mom — so I grew up listening to modern country, '90s country, but I also listened to a lot of older country like George Jones and Loretta Lynn and Dolly Parton. I was taught to appreciate all that. I remember going to my grandparents’ house, and my mamaw would get out her record player and her eight-track tapes and listen to those artists. My grandparents were a big influence on me and they were also big fans of the '90s line dancing craze so, when I was younger, they would take me out to line dances, and I would be part of their line dancing group pretty often.

I started playing music when I was about 12. I’d always had an interest in music — I was in chorus in school and in theater — but I really didn’t have an interest in traditional music until a little bit later, when I started taking guitar lessons. I started taking banjo not too long after that, and I attended a local camp here called Mountain Music School. I attended Mountain Music School in its second year, and it was there that I really got introduced to the region’s music — people like Papa Joe Smiddy — but especially I remember the Whitetop Mountain Band came one day and played for us, and Emily Spencer, who’s a really wonderful banjo player from Southwest Virginia, was one of the leaders of the group. I just remember seeing and hearing her play the banjo and I thought, “That’s what I want to do.” Emily’s playing really struck a chord with me, I guess you could say. At Mountain Music School, I learned how influential Southwest Virginia’s music is on the world’s music. I really had no idea about people like Dock Boggs or the Carter Family until I started going to Mountain Music School and hanging around the folks that helped organize the camp, like Todd Meade and Julie Shepherd-Powell and some other folks.

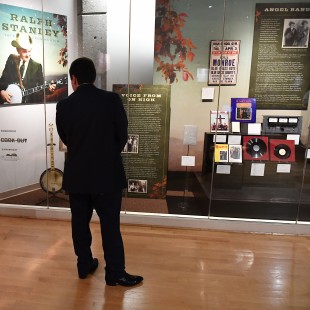

The Empty Bottle Stringband at the Carter Family Fold. From left: Ryan Nickerson, Tyler Hughes, Kristal Harman, and Stephanie Jeter.

One thing we’ve talked about often is how the women who shaped the music of Southwest Virginia, what a great impact they’ve had on both of us, and I know one woman we really admire and look to as an inspiration is Janette Carter, who established the Carter Family Fold in memory of her parents Sara and A.P. Carter. Why do you connect with Janette’s music and what does her life’s work mean to you?

I, unfortunately, never got to meet Janette, even though I’d been to the Carter Fold several times and played at the Fold, but I didn’t start going until after she had passed away. On one of my first trips to the Carter Fold, I bought Janette’s book, Living with Memories, and read it. I was just so impressed with her because she overcame so much. The Carter Family … the Carters were in no way rich, especially growing up in Poor Valley in Scott County, Virginia … so Janette really rose above the poverty that most people see in that region. She was a radio star as a teen and she came back home, married, settled down to raise her family and went to work at the local school — she was a lunch lady there. She still played. She played the autoharp and guitar and sang songs. She felt so strongly about her family’s influence on music and her father’s music that she wanted to keep this promise to him that she would help carry on the legacy of the Carter Family. She gave up her job and really risked pretty much everything to open their grocery store up as a venue, a concert hall. I think it really says a lot about how brave she was, as a person, because there was no guarantee that opening up a 20-by-20 grocery store and putting chairs in it and asking people to come out and pay to hear music would work, especially in a region that’s impoverished.

I do admire her for that. In an interview I’ve heard with her, Janette said, “One day I was working and I thought, ‘I have some talent and why don’t I use it,’” so she started putting on school programs and traveling with her music a lot. Another woman who has really influenced your work and music is Sue Ella Boatright-Wells; she is part of organizing so much of the region’s community music scene. Tell me about her.

Sue Ella Boatright-Wells is also from Scott County — she lives in Scott County today. She doesn’t play music, but old-time music fans who dig deep have probably heard of her father, Scott Boatright, who was really good friends with the Powers Family and Dock Boggs and the Magic City Trio; Scott played with several bands in the area. Sue Ella grew up with music in the home and, when she took her position at Mountain Empire Community College in Big Stone Gap, she wanted to use that as an outlet to help preserve that music.

Sue Ella has been an influential part of the Home Craft Days festival at Mountain Empire Community College, helping to get local artists and musicians to the campus each October to showcase their art and their music. She is the mastermind behind Mountain Music School, which was such a huge influence on me, and even today, Sue Ella works tirelessly to help support efforts by the Crooked Road and their Youth Music Initiative and the Junior Appalachian Musicians program, which is now in Wise County. She works very hard to see that those programs succeed and are able to expose children to the music, especially our youth here that probably didn’t grow up with this music. As in any rural area, money never flows freely in the form of grants or government funding for the arts, so it’s sometimes a pretty difficult fight to find funding and to find ways to make these programs go, but Sue Ella never backs down. She’s always got a plan and she always works extremely hard to see that these programs do happen and that they happen to the best of their ability.

I’m very, very lucky to call Sue Ella a friend. I’ve looked up to her for a long time and she was incredibly encouraging to me, coming along as a banjo player. After a few years of attending Mountain Music School, she asked me to come on and be an instructor there, and today I co-direct the program and try to do a lot of work with Sue Ella to see that these youth music programs happen. I do try to model my work after Sue Ella’s.

I guess most people wouldn’t think that organizing music or organizing dance and art, especially in the mountains … people probably don’t put the same value on that as maybe somebody who organizes a food drive or a fundraiser to build a park or whatever. They probably don’t see the same value in promoting the arts because that seems intangible. But advocating for local music and arts is such an important thing to do to build community. Unfortunately, we live in a time where technology, as great as it is, is diminishing our abilities to be together as communities — just humans, one-on-one — and to share experiences like music. That’s why I feel that it’s so important to continue to organize events and programs, especially for youth, to show that this music has continually brought people together for years and years and, hopefully, will continue to bring.

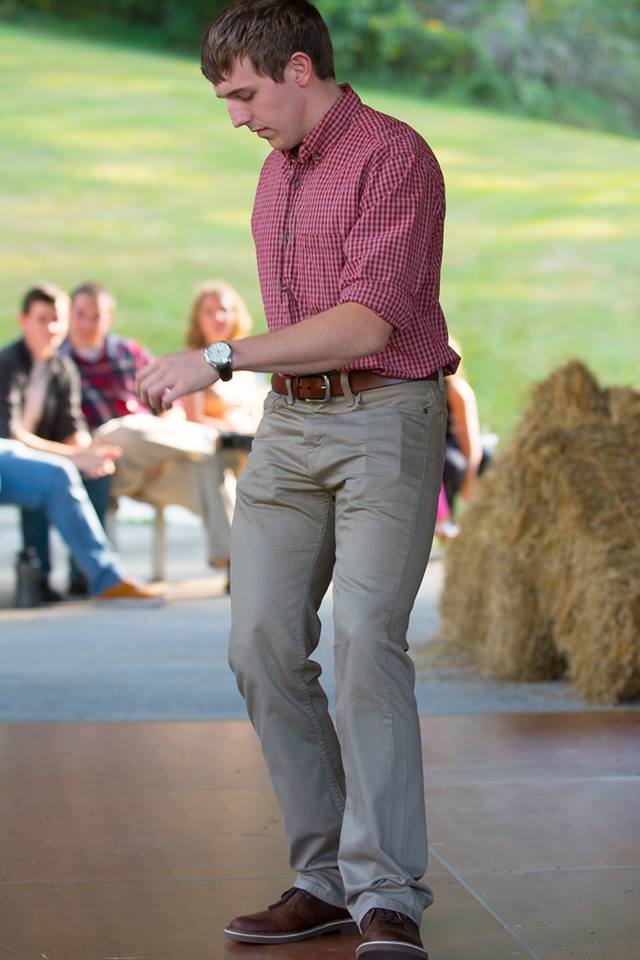

Tyler Hughes demonstrating flatfoot dancing at the Papa Joe Smiddy Festival. Photo by Dan Boner.

Speaking of community and music bringing people together … you’re a square dance caller and a prize-winning flatfoot dancer, so I want to hear about your background in dance.

I started learning to dance not too long after I started learning the banjo. Probably the first person that ever showed me anything was Anndrena Belcher; she was living in Scott County at the time and she’s also someone that I look up to. Anndrena really does see the true value of our own personal stories and songs, and she’s a really wonderful musician and writer and storyteller and dancer. She was the first person to ever show me any steps; I was lucky, I got to do several workshops with her around Wise County where we went out and taught other students to dance.

Anndrena teaches dance not just to preserve or carry on the tradition, but simply to do what any kind of art is created for: self-expression. I thought that was very important and something that we shouldn’t lose when we are passing on these cultural traditions. So often in the region, we just talk about how endangered our way of life can be, and how some tunes and music aren’t getting played as much as they once were, and some dances aren’t being danced as much as they once were. It is important to preserve these arts for the historical aspect, but also for the self-expression and the social aspect. For a long time, one of my very best friends lived here in Big Stone Gap, Julie Shepherd-Powell, who’s a really wonderful banjo player and also an award-winning flatfoot dancer. She taught me a whole lot and she spent a lot of time with me at some workshops and, just on the side, teaching me different dance moves.

Julie Shepherd-Powell is also a fine square dance caller, and I know not too long ago you hosted a square dance in Big Stone Gap, and it was one of the first that had been held there in quite a while.

I started to learn to call square dances about two years ago. For a long time, I was head of a contra dance organization at East Tennessee State University, where I went to college. Along the way, we were having a lot of fun with contra, but we wanted to experiment with square dances because square dances were much more closely associated with old-time music, the music we were playing in the program. We looked around and we only knew a handful of square dance callers, and we found out that there was no young person within our immediate crowd calling square dances in Johnson City. So I took it upon myself to try to learn some and, today, I’ve probably mastered about eight to 10 dances. In December, I pulled together several organizations — the Big Stone Gap Parks and Recreation Department, a couple local business sponsors, Auto World, and the local grocery chain Food City all pitched in and several community members baked goods and food, and we all met here at an old Girl Scouts cabin. Some wonderful friends of mine, Bill and the Belles, came over and played the music and we had the dance and it was successful. The dance was well-attended: People were really receptive and supportive. Dance is a very important tool to get people together to socialize and share experiences about what’s happening in their community.

While we’re talking about Wise County, another woman from that area that you and I both admire is Kate Peters Sturgill, the great songwriter. Tell me why you sing her songs.

Kate was from Josephine, Virginia, a little coal camp just below Norton out in the county. She was a wonderful guitar player and singer but, more than anything, I love her writing. I’ve always said she was one of the most poetic writers from the region that I’ve ever come across. She really puts her passion for her home community into her writing — songs like “My Stone Mountain Home,” which I perform now. Kate is not an incredibly well-known artist — most people, if they’ve ever heard one of Kate’s songs, it’s probably her best-known gospel tune, “Deep Settled Peace” — but she wrote a whole handful of beautiful songs and many of them deal with our home county. She wrote “My Stone Mountain Home” about the mountain chain that runs down Powell Valley and between Appalachia, Virginia. She also wrote about the Trail of the Lonesome Pine, which has a lot of significance here. The book and the outdoor drama by that title, written by John Fox Jr., were based loosely on local people and events here in Big Stone Gap. The context still exists to have Kate’s songs sung and played here.

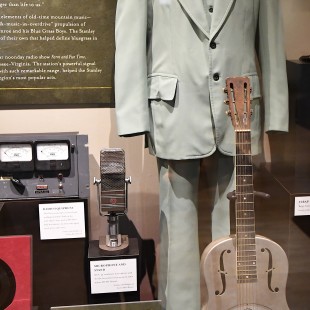

The Empty Bottle Stringband playing for the extras party for the film Big Stone Gap at the Trail of the Lonesome Pine outdoor drama. Photo by Sam Gleaves.

I really enjoy the way that you use humor on stage when you perform. That’s a real tradition in country music. Why do you think it’s important to be funny and entertain as you present this music?

I think that often, especially as old-time musicians and musicians who want to preserve early country music in the form it was created in, we sometimes forget that we’re pretty much the only ones who are thinking so deeply about the historical context of the way the instruments were played or even what the songs were saying. When we take those out to a wider audience — unless you are playing for a special audience that is there to have this historical significance explained to them — people are still coming because it’s music, and music is fun and entertaining. This music is light-hearted or it can be really deep and emotional, and I think people want to feel all of that.

I think the best way we can present the music, truly, is putting it on as a show, because that’s the way it’s always been done. People in the 1920s weren’t playing “Cottoneyed Joe” or “Turkey in the Straw” to historically preserve the tune from the way it was played in the 1860s. They were thinking, “This is fun, this is entertaining.” I don’t think that’s anything we should forget, especially if we want to bring old-time music to a wider audience. It doesn’t have to be as if we’re presenting a piece from a museum.

I love to hear you tell a good June Carter joke, but in closing, I know another female musician and songwriter we really admire is Ola Belle Reed, and she once said in an interview, “We all need each other, whether we know it or not.” I think that speaks so much to what community organizing is about and what old-time music is about. Being a community organizer and someone who has put old-time music at the center of their life, can you talk about that?

I think that’s definitely true. Unfortunately, we still live in a world where stereotypes get placed on everybody. We all do it, whether we mean to or not. When most audiences think of old-time music, they probably have in mind a hillbilly character or, perhaps, only white men playing it or it being associated heavily with Protestant faiths — the stereotypical images of Appalachia that are often portrayed. Often, old-time music probably evokes those same stereotypes to people outside the region, but the beautiful thing is that old-time music is just as diverse as the region itself and, as anywhere else in the country — or the world, for that matter.

Whether it be old-time music or pop music, music transcends the barriers that society places on all of us. It really doesn’t matter whether you’re rich or poor or black or white or gay or straight; however you identify, music can touch us all and affect us all. If we aren’t brought together through some type of connecting bridge like music or dance or community events, then we may never know that we’re sharing the same experiences and how important it is — that we’re not alone. Often, I think we get bogged down as individuals in our lives but, by coming together through art, we find many others who are sharing those same feelings and can relate to us. When we relate to each other, there’s empowerment and there’s a healthier sense of community.

Lede photo by Kristen Bearfield.

Sam Gleaves is a folk singer and songwriter from Southwest Virginia. His latest record, Ain’t We Brothers, is made up of stories in song from contemporary Appalachia, produced by Cathy Fink.