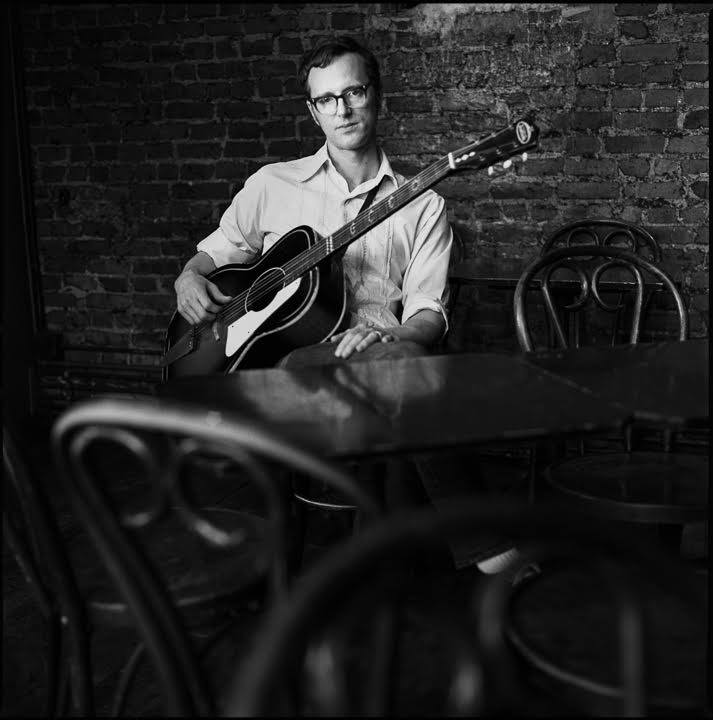

If you’ve picked up a copy of the Punch Brothers’ new EP, The Wireless, then you’ve heard the work of Gabriel Kahane — the Brooklyn-based songwriter penned “Sleek White Baby” for the band. But Kahane’s skills far exceed that single song; in fact, he’s got a steady track record of beguiling works that range from his 2006 collection of short, hilarious interpretations of Craigslist ads to full-blown symphony commissions. Last year, Kahane released a stunning LP, The Ambassador, which examined the city of Los Angeles through songs that were stirring and poignant. With each listen, the album slowly reveals itself to be a richly complex and breathtaking work.

Kahane followed the summer release with a staged presentation of the record, which premiered in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, last October before moving on to the Brooklyn Academy of Music and UCLA. For much of the past year, Kahane has been crossing the country in support of the album.

Your songs aren’t what most people would consider traditional folk or Americana music. But some of your work, like The Ambassador or Gabriel’s Guide to the 48 States, is still about distinctly American experiences. Is that something you’ve focused on in your work on purpose?

I don’t know that it’s something that I’ve thought about deliberately, but I did have this revelation at the beginning of 2014. I’d been sort of continually frustrated by journalists writing pieces about genre, people writing about my music and writing about genre like, “He’s a composer and he’s a songwriter!” I was doing this Q&A at some festival and suddenly it occurred to me that the thing that really unifies all of my work as a musician — whether if it’s in an orchestral realm or in a club setting where it’s just me and a piano and a guitar, or me with a band — is that I love telling stories. I think that the spiritual kinship that I feel with the folk tradition is very much about storytelling.

I realized that the best way to sort of side-step a conversation about musical sophistication — or why is this song in 11/8 or what are those weird chord changes — is to just make it clear that I’m first and foremost interested in telling stories, and whatever musical vocabulary is necessary to tell those stories is the vocabulary that I will go after. I am glad that I have a broad musical palette to draw on, but that musical vocabulary is only worth as much as it can enhance the telling of a story. If it becomes about doing some weird polyrhythm or some weird harmonic thing or some weird chord change as an end to itself, then I think it sort of defeats the purpose for me.

So you draw on your musical background just as a means to illustrate these stories as colorfully as possible, as opposed to sticking to one particular style?

I wouldn’t even say telling as colorful a story as I can as much as identifying the story I want to tell and telling it as truthfully as possible … whatever that means. Obviously, some of the stories that I tell in my songs are fictional and others are not. But the music, for me, is really in service of the story, and that’s how I would think of it.

You premiered the staged version of The Ambassador in Chapel Hill almost exactly a year ago. How has the year since been for you?

There’s been a lot of uplift, and there’s also been some frustration. The positive things that have happened are that I’m really, really proud of the piece that John Tiffany and Christine Jones and I made with those seven extraordinary musicians. I feel like we set out to try to find a different way to tell stories on stage through music, and it felt — both from a critical standpoint and an audience standpoint, in Chapel Hill and New York and Los Angeles — it felt like we were really getting our message across and that people were engaged in what we were doing and were moved by it.

The frustrating part is that, I guess there were sort of two frustrations. One is that my record label had basically checked out before it even got to BAM. To a certain extent, it’s understandable. The recorded music industry is in a total free fall. But it was definitely frustrating, given that their line from the outset had been, “Oh, this is going to be a slow burn,” and we had the rare luxury of a second phase of the album built in in the form of this staged piece in Chapel Hill and at BAM. There were some pretty serious missed opportunities in capitalizing both on the really generous press, and that we’d made something that we felt really good about, and that audiences were responding to in a really beautiful way. That was frustrating, and we’re still very much hoping to stage it again, but I don’t know when that’s going to happen, exactly. And then there’s been the other side of performing these songs, which has been outside of the context of the stage version.

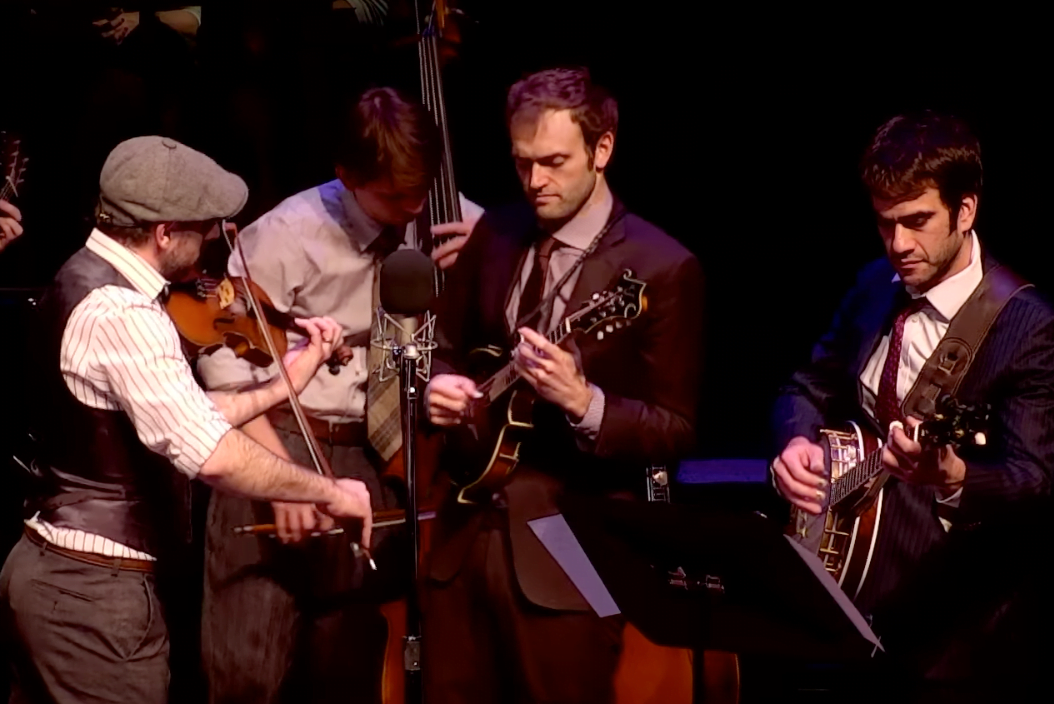

This year, I’ve spent a lot of time on the road with the Punch Brothers, and will continue to do so in December, and that’s been really, really wonderful. Their audience has been incredibly generous toward me. And I think part of that is just a function of Punch Brothers training their audience in a beautiful way to be great listeners. I’ve had a really extraordinary time in a lot of really unexpected places singing these songs and telling these stories … and finding that their audience has basically been always game for it. That’s been a huge pleasure. It’s still a slog. Being a songwriter is a slog.

Even though you have really different styles, your and the Punch Brothers’ music fits together really nicely. Can you tell me more about your musical relationships?

I think something that Chris [Thile] and I have in common — and I don’t want to speak for him, but I’m going to speak for him, because he’s not here — I think we’re both interested in tricking people into listening to music that is more complicated than it sounds … which, to put it another way: I think we both are interested in making sophisticated music that sounds simple. I think very often, in technical terms, it has to do with writing melodies that are very singable, but having a shifting and murky harmonic space underneath that.

From a rhythmic standpoint and a harmonic standpoint, we’re trying to both honor the tradition of American song while also pushing against the walls that confine those forms. My suspicion, just based on the extent to which the audience has been receptive to my music, is there is some kinship there. On the surface, I’m playing piano and electric guitar, and it’s pretty far from what Punch Brothers are doing, but there are a lot of similar values there.

Have you found it frustrating to have been pigeonholed into specific roles as just a composer or just a songwriter?

Yeah, and I think the thing that was probably most frustrating for me for a long time — and I think this is finally starting to change — is that there was this idea that somehow became prevalent that I was a composer who started writing songs … when, in fact, it was the other way around. When I finished college, I moved to New York and I started writing songs. In 2006 was when I wrote Craigslistlieder, which I wrote initially to just sing in clubs and in bars, and the fact that it was kind of a classical piece was secondary. There’s nothing unapproachable about that music. The texts are so incredibly contemporary and so bawdy, like, “You looked sexy even though you were having a seizure,” or whatever. And so it was through that I started getting invitations to do classical commissions.

Then, for whatever reason, I was written about more in the context of being a composer for a while than being a songwriter. That was frustrating to me because I feel like I am first and foremost a songwriter, and actually, I’ve taken some steps to kind of limit what I do in the strictly classical world as it becomes more and more clear to me that my heart is really in being a songwriter. That’s both what I love doing the most, engaging in audiences in that way. And I think it’s also where my skill set lies the most clearly — in the relationship between music and words, and putting them together.

What do you see happening for you in the next year? Do you have a new record planned or are you going to keep working with The Ambassador?

I’m doing some tours in the Spring. I’m doing a tour with Brooklyn Rider, the string quartet, and that will be a lot of stuff from The Ambassador and also some other chamber music of mine for string quartet and voice. And I’m doing a tour with my friend, the pianist Timo Andres. But, yes, I am getting started on a new record. I thought I was going to be working on a big adaptation of a big novel, which will remain nameless for various reasons, and ultimately I decided that I wanted to do something that grew more from my own imagination.

The last three big projects that I’ve done — which I would consider to be The Ambassador, Gabriel’s Guide, and before that, the musical February House — they were all adaptations of one kind or another. Even though The Ambassador was all original words and original music, a lot of the stories that I’m telling are stories that are inspired by other popular culture — film, fiction, architecture, so on and so forth. There’s this way that a lot of what I’ve been doing has been referential. Not to say that I’m going to write a hyper-confessional singer/songwriter record, but there is something really appealing to me about making a new body of work that isn’t mediated by some source material, where I can just wake up in the morning and write really, really intuitively and not have to triangulate with some other source.

Photo credit: Josh Goleman