When M.C. Taylor presented his idea of a Hiss Golden Messenger holiday record last fall, the label team at Merge Records began scratching their heads. Anyone familiar with the singer-songwriter would agree he just doesn’t seem like the type.

But this juxtaposition is at the heart of Taylor’s intentions to create a more relatable soundtrack for a season he felt has been oversimplified by an excess of enduring holiday hymns and hits. As an artist, he has never connected with the holiday music resounding in big box stores throughout the season. Last winter, in the face of inconceivable global hurt, this flamboyant backdrop felt particularly jarring.

After he wrapped up the Quietly Blowing It LP in the summer of 2020, Taylor still felt the tugging desire to create. While the year stormed outside the tiny window of his home studio in Durham, North Carolina, he was determined to capture authenticity within an often-romanticized season. What began as yet another coping mechanism soon took shape as a Hiss Golden Messenger album, O Come All Ye Faithful.

“There were definitely moments when I was making it when I thought to myself: ‘Am I insane? Has the pandemic made me lose my compass on what my music is meant to do?’” Taylor tells BGS. “But once we were a couple of songs into it, everything sort of clicked into place. I was like, ‘This totally makes sense. This sounds like a Hiss record, actually.’”

A self-proclaimed “second-guesser,” Taylor found creative refuge in a more interpretative state of mind, rather than relying solely on his usual songwriting process. His only directives from the start were to make a record that feels “lush, slow, and contemplative.” Despite these uncharacteristic parameters, his purist approach to the album captures the poignant emotions of closing out a season, or a chapter.

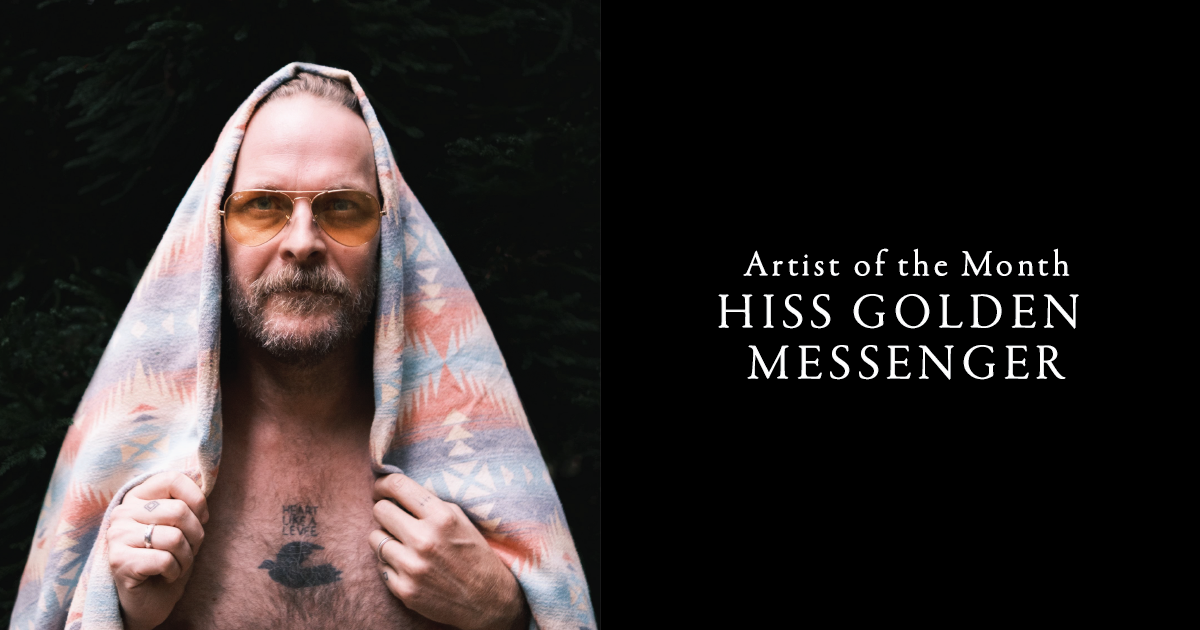

As the year winds down, enjoy our BGS Artist of the Month interview with Hiss Golden Messenger’s M.C. Taylor.

BGS: The holiday album has been done by countless artists. What did you feel you could contribute or expand upon within this enduring tradition, and why is that important to you at this point?

Taylor: Well, I should say at the outset that I’m certainly not an expert on holiday music. I’ve realized that even more over the past couple of weeks when people, knowing that I’ve just made this record, will be like, “Oh man, you’re into holiday music. Have you heard this or that record?” And I’m like, “I haven’t heard any of it.” My collection of holiday records is remarkably thin. I have a handful of “holiday records” that I consistently return to.

But I’ve noticed that often the music I hear, the stuff that seems to get played out in public during the season, doesn’t hit the emotional note that I’m feeling. And it doesn’t really resonate with anyone I know either. This big, brash, brassy, super uptempo, almost turbocharged holiday music seems to be the background to this season, but I started to feel like maybe it doesn’t have to be. Maybe I can come up with something that feels more in step with how everybody I know feels around this time of year.

When did you write these three original tracks, and how do they fit into this concept?

I keep hedging my bets by calling it a seasonal record; I’m not sure how that’s exactly different from a holiday record. But these were all written with this record in mind.

The first one, “Hung Fire,” is a very intimate song and a meditation on this time of year and how hard it can be on many people. It’s sort of a meditation on suicide in a way, which is a bit heavy, but I felt like there was a place for it on this record. Aoife O’Donovan sings on that one. That was the first stuff that she sent back to me after I asked her to sing, and I was just like, “Oh my God!” She is an absolute ace in the hole. She’s one of the greatest singers that I know.

Lyrically, “By the Lights of St. Stephen” is loosely based on this old seasonal song called “The Wren” that I learned from a record by an English family acapella group called The Watersons. So, if you ever find that song, certain lines are similar, and then I kind of take it off into a different place.

I felt it was incumbent on me to nod towards Jewish seasonal traditions. My wife is Jewish, and my kids identify as Jewish, so we put Woody Guthrie’s “Hanukkah Dance” on there. And I was trying to work on another one, but it’s hard to fit the word ‘Hanukkah’ into a song. I had this idea of a song that featured candles, a big part of the tradition. I don’t know if anyone else hears this. Probably not. But I think of “Grace” as the other Hanukkah song.

From your perspective, why did “Shine a Light” and “As Long as I Can See the Light” work well with this theme?

I had a long list of songs I felt could be seasonal songs by association. Meaning if I put them together with other songs like “Silent Night” or “O Come All Ye Faithful,” they could be, in that context, interpreted as a song as it spoke to this particular time of year. Thematically, the record returns to the idea of light and dark, searching for light or a spark during a season that feels quite dark. It also uncovers the notion that we don’t understand light without darkness. I’ve always loved those tunes, and I wanted to see if we could do something to them that made them feel like they were supposed to be on the record.

When we spoke earlier this year, you felt uncertain about getting back on the road after adjusting to life at home. With your tour starting up again, has that feeling changed?

One thing I’ve grown to miss over the past couple of years, aside from playing live in front of people, is routine. And a tour gives me the closest thing that I have to a regular, everyday routine. I’ve always been a creature of habit, but the past couple of years brought this idea home that I function best with like a daily regimen; I like to know what I’m going to be doing. And I can’t say that I had that during this pandemic. Certainly, many of the traveling musicians I know were at loose ends as to what to do with themselves.

How did the pandemic and all the political fury affect your approach to this record?

This idea came in the fall of 2020, a few months after I finished Quietly Blowing It. Again, the approach goes back to this need for routine. I needed to be working on something that kept me busy in the days, and I also needed to be working on something that made me feel peaceful at a time full of chaos and anxiety. So, that was where I went. Music has always been a pretty dependable place for me to go. I’m not even sure that I would have made this record had we not been living in such a chaotic time that felt so full of uncertainty and grieving.

Growing up, what were your family’s traditions surrounding the holiday season? How do you feel that translates in these musical selections?

We celebrated Christmas, and my family was pretty tight. I grew up in Southern California, so I have this specific set of memories, like a beautiful, sunny Southern California Christmas Day — not the norm for most. Strangely, the soundtrack to Camelot was a constant. If you were to ask anybody in my family what holiday music you listen to, everybody would say Camelot. It took me until I was a full-grown adult to realize that that is not technically a holiday record. But somehow, it’s still really associated. If you place songs in the vicinity of the holidays, your brain will start making a connection.

Are there any particular points of nostalgia within your selections here?

It’s kind of a nostalgic feeling record, but I don’t know that it comes from childhood. The songs are not necessarily from my childhood, but I feel like the emotions within the record speak to a bittersweet set of emotions that have been with me since I was a kid. When I was quite young, I remember talking to my mom about the holidays, and she said: ‘This is always a really hard time of year for me.’ And I understood what she was saying. There is a sense of grief that comes with the closing of a year. I feel like that grief can be echoed in the natural world outside as we see things closing up for the winter before the hopefulness that comes with spring. My feelings about the winter holidays have always been a quiet time of contemplation.

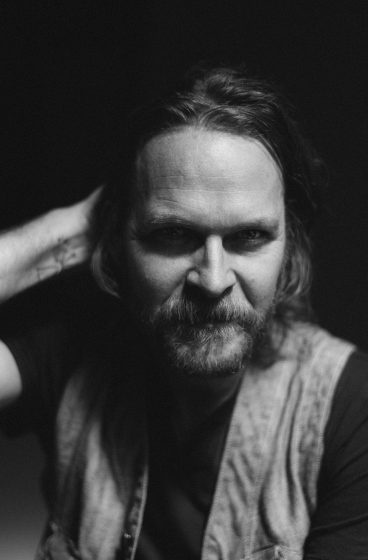

Photo Credit: Chris Frasina