Before becoming the psychedelic guitar-playing icon of the Grateful Dead, Jerry Garcia was already living a life completely dedicated to music. Heavily immersed in the folk idioms that coalesced with the beat poet scene in San Francisco — and in the peninsula towns of Menlo Park and Palo Alto — in the beginning of the 1960s, Garcia’s concentration, determination, and passion for musical collaboration planted the seeds for a force that would not only influence the world in song, but that would let loose a seamless tie to multiple genres through multiple generations. What’s now viewed as Americana, Garcia was creating with the Dead right from the outset. His impact looms far and wide, perhaps even greater as the years since his passing roll on. From the bluegrass world of the McCourys to esteemed guitarists like Mike Campbell of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, David Hidalgo of Los Lobos, and David Rawlings, to jam bands like Leftover Salmon, and the current generation of musicians like the National, Jenny Lewis, and Ryan Adams, Garcia’s ethos is being deeply felt and utilized.

Garcia had a mind hungry for knowledge and interested in art, comics, and horror films, even as music ran through his family. After initially getting an accordion for his 15th birthday and successfully trading that in for a guitar, the quest for constant improvement was born as he devoured the styles of Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Buddy Holly, and Bo Diddley. As the ‘60s approached and the initial rock boom faded, Garcia and his friend (and soon to be Grateful Dead lyricist) Robert Hunter found themselves in the middle of a very fertile Bay Area folk scene. Being steeped in Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music led to a fascination with the Carter Family and then Flatt & Scruggs.

It was at this time, in 1962, that Garcia began his complete immersion into the banjo and the bluegrass style of Earl Scruggs. He formed the Hart Valley Drifters with Hunter and David Nelson (later of New Riders of the Purple Sage and the Jerry Garcia Acoustic Band), and the scene grew to encompass the likes of Eric Thompson, Jody Stecher, Sandy Rothman, Rodney Albin, Janis Joplin, Jorma Kaukonen, David Crosby, Paul Kantner, and Herb Pedersen. The Hart Valley Drifters performed at the Monterey Folk Festival in 1963 in the amateur division and won Best Group, and Garcia took the Best Banjo Player award, which strikes with irony as, throughout his career, Garcia would never consider music to be a competition of any kind. He was more into turning people on.

While absorbing as much music as possible and focusing on his craft with diligence, Garcia came into cahoots with people like Ron “Pigpen” McKernan and John “Marmaduke” Dawson through a string of continuous collaborations and a rotating cast of characters at joints like the Boar’s Head, Keppler’s Bookstore, and the Tangent. McKernan was the blues aficionado with the biker looks and heart of gold who would lead Garcia into the electric blues band the Warlocks, which then became the Grateful Dead, while Dawson would be the one who had the canon of songs for Garcia to base his pedal steel guitar learning around to form the New Riders of the Purple Sage.

But it was on a cross country road trip with Rothman in 1964 that Garcia met David Grisman, the young mandolin player to whom Thompson had tipped him off. It was at Sunset Park in West Grove, Pennsylvania, where acts like Bill Monroe and the Osborne Brothers were featured, where Garcia and Grisman first did some pickin’ together, and a friendship was born that would lead to musical ventures that would have more than a lasting impact.

Both Garcia and Grisman were imparted with some crucial advice from Monroe, which was to start your own style of music. Garcia, no doubt, led the Dead (as much as he refused to admit to any leadership role) to their unique musical domain, while Grisman created his own “Dawg” style of music that was the precursor of “New Grass” in the ‘70s. According to Grisman, “Jerry was always the true renaissance music man.”

While each had gone on to create their own paths, it was 1973 when they started hanging out together at Stinson Beach, picking and having fun, when Peter Rowan (a former Bill Monroe Bluegrass Boy member) joined in along with legendary fiddler Vassar Clements, and, needing a bass player, John Kahn was brought in. Old & In the Way was born. In typical Garcia nature, the musical fun led to some local gigs which, thankfully, were recorded by Owsley “Bear” Stanley. With the guitar and the Dead being Garcia’s main drive, getting back to the banjo and picking with his pals in Old & In the Way was not only stress free, but fun and a piece of his musical puzzle that really exemplified how the muse consumed him. It wouldn’t be out of the norm, at the time, to find him in the span of a week or two playing gigs with the Dead, Old & In the Way, and one of his other musical soulmates, Merl Saunders.

The release of Old & In the Way, taken from Bear’s recordings at the Boarding House in San Francisco in October of 1973, hit the world in 1975 on the Dead’s Round Records label. It was through the Dead Heads fan club mailing of a 7-inch, 33 rpm sampler that many fans got their first dose of Old & In the Way. Many of that generation — and a few that followed — were exposed to bluegrass thanks to that release. The album continued to turn on the masses and was widely respected as one of the best-selling bluegrass albums of all time.

While fame was never of interest to Garcia, the expansion of musical consciousness was, perhaps, the most beneficial and unintended consequence of his popularity. Just like the Dead were doing with their music — turning kids onto Merle Haggard, Buck Owens, and Johnny Cash songs — here, Garcia and Old & In the Way were turning rock and rollers onto bluegrass and the songs of Peter Rowan, the Stanley Brothers, and Jim and Jesse McReynolds. The aspect of turning people on to music was certainly not limited to bluegrass, where Garcia was concerned. The Jerry Garcia Band was his outlet for a good 20+ years, wherein he’d groove to just about any and everything. Motown, Louis Armstrong, Los Lobos, Allen Toussaint, Irving Berlin, Bob Dylan, Bob Marley, Van Morrison … the stream of tremendous musical taste was just about endless. And, of course, adding his own flair, passionate vocals, and one-of-a-kind guitar to it all made for hundreds of satisfying shows and numerous albums.

Jerry Garcia made music that was loaded with adventure. Improvisation was his nature, always seeking out what was around the bend, never wanting to play the same thing the same way twice. That adventure is what drew so many to him and his music. That adventure lives on, not only eternally in his music, but also through the lives, songs, and good deeds of those he inspires.

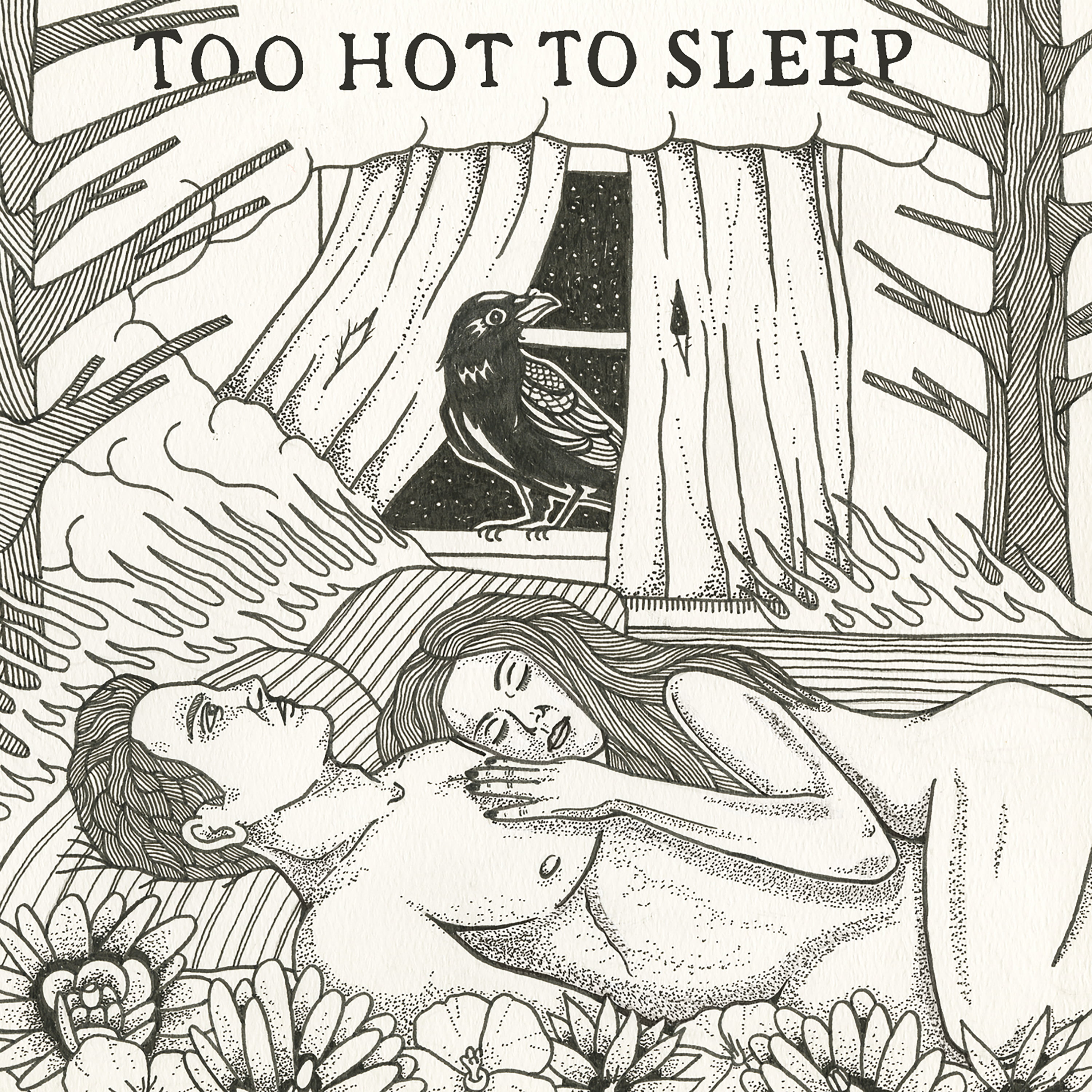

Illustration by Zachary Johnson