Peter Rowan is a serious wellspring of knowledge about 20th-century music. It’s a wild ride to interview him about a new project — in this case, his recent Hawaiian-inpsired album, My Aloha. In a half-hour conversation, we touched on the early Grand Ole Opry, varieties of New Orleans blues, Hawaiian mandolin playing, and plenty more. His obvious breadth of knowledge squares with a freewheeling half-century career: He’s studied with masters like Bill Monroe and Carter Stanley and collaborated with brilliant contemporaries like Jerry Garcia, David Grisman, and Clarence White, not to mention his forays into country, reggae, Tex-Mex, Irish, and now Hawaiian music. By now, his surprises shouldn’t surprise us.

We usually expect our bluegrass musicians to stick to bluegrass music, just like we expect B.B. King to play the blues. Try to imagine Ronnie McCoury or Tony Rice making a record with a Tibetan throat singer. But somehow Peter Rowan — a true bluegrass guru, if there is one — has managed to consistently defy this expectation. He’s made an identity out of idiosyncrasy.

And unlike some legacy artists who “collaborate” with peers solely for the sake of novel juxtaposition, when Rowan makes Irish music with Tríona Ní Dhomhnaill or Tex-Mex with Flaco Jiménez, he doesn’t just collaborate; he immerses himself. He absorbs. Bill Monroe told a young Peter Rowan, “If you can learn my music, you can play any kind of music.” Coming from Monroe, that sentiment could’ve been taken as territorial ego, as bandleader bluster. But Rowan took Monroe’s words to heart. He’s turned a foundation in bluegrass into a life-long dedication to diving deep into new musical languages.

It’s tempting to conclude any survey of Rowan’s career by contrasting Monroe and Rowan as the founder vs the experimenter, the father vs the prodigal son. This sounds satisfying but largely misses the point, because the Father of Bluegrass didn’t respect genre boundaries, either. Combining influences from far-flung musical worlds was exactly Monroe’s bailiwick. Seventy years in the rearview mirror, however, his string band innovations are often taken for granted. It’s easy to forget that Bill Monroe, himself, stole mandolin licks from Hawaiians, studied blues with Black guitarists, reimagined fiddle songs from the old folks back home, and generally told the status quo where to shove it. So, if Peter Rowan’s new Hawaiian record makes you scratch your head, remember he’s just carrying on the family tradition.

I’ve been listening to your My Aloha record. It’s beautiful and spare and cohesive. It’s great. Even though I knew you did all kinds of projects and recorded a lot, this one surprised me. How did it come about? How did you decide to do a tribute to Hawaiian music?

That song “Uncle Jimmy” kind of explains it. When I was four years old, he came back from Hawaii, from New Caledonia in the South Pacific, where he’d been working with the Navy. He had a ukulele and grass skirts and coconut bras. He handed them out in our living room. There’s a photograph … I wish I had included it … with all of us decked out — him with his sailor cap on and he’s doing that vaudevillian knee-whacking thing they did back then, that visual comedy thing where you cross your hands in front of your knees and it looks like your knees are passing through each other. So that was Uncle Jimmy. He always said “hubba hubba ding ding,” and I never knew what that meant. When I was over in Hawaii meeting the two Hawaiian players on the record — you know, you talk in story over there — and as I explained Uncle Jimmy, they said, “You’ve got to do this! You’ve got to finish this song. This is really part of the story.”

So you decided to record in Hawaii. What was that like?

I sort of fell into their whole approach, is what happened. I’ve always gone to Hawaii over the years, and it’s so musical. And the land itself seems to have some sort of enchanted healings that themselves turn into music — what they call Mana. I’ve been playing the last few records of bluegrass and one twang record out of Texas. I was just thinking, why am I so attracted to this sound? Really it’s because I heard it first. I heard a ukulele before I heard anything else. Uncle Jimmy was playing ukulele, and I learned from him. I learned “Five Foot Two, Eyes Of Blue,” “Bye Bye Blackbird” and all these tunes. And Uncle Jimmy, he didn’t have a completely happy life. He didn’t pass on as a fulfilled person. But he had that willingness to go out on a limb. He even did some shows with me and my brothers.

So he was an influence on you during a really formative period.

Well, that’s the first instrument I learned, the ukulele. It had never dawned on me that it was going to open any doors. A few years ago a friend of mine made a baritone uke, a nice one, so I started playing it and songs started coming. When I would go over there [to Hawaii], you know, I’d hit the water and swim and then come back to the instruments and play. You’re in a zone. It’s a different zone. And the songs started coming. It’s more of a watery thing, a little bit sunbaked. That’s really why I did the project, because I was writing the songs.

They definitely channel that Hawaiian vibe, or what I think of as that mid 20th century Hawaiian sound. It sounds like it’s a tribute to a period of time, too, that era in the 40s when Uncle Jimmy was going over there.

They’re also more ragtimey chord changes like my parents would’ve listened to. Also there’s a strong connection to Jimmy Rodgers. I loved those chord changes from the 30s, those Jimmy Rodgers elements. I did a record with Jerry Douglas called Yonder, and we touched a little bit on this real old time sounding guitar and dobro songs. This reawakened that approach.

When Hawaiian people hear my interpretation of Hawaiian music, they sing along. They’re very humbled. It’s just like in bluegrass and old time music. There is a lineage of players, and I became fascinated with the history of the whole thing. It kind of cleared my palate to make this next project for Rebel Records, which is sort of my story as it relates to the Stanley Brothers. It helped. Singing Hawaiian music is so different. Singing falsetto is a tradition in bluegrass, too. In bluegrass you have to find that vocal break point with a harder, sharper edge. Hawaii gives you a soft break point. It also gives you more range — you can sing lower and then go into a higher range of falsetto singing. Bluegrass, you know, is very tight. You’ve got to jump through the hoop. It’s like that rabbit in a log with the hound dog after you — bluegrass chases you. You’ve got to make your breaks and vocal turns really fast. Hawaii just gives you a lot more time to make those vocal breaks. So different from bluegrass. It was like, “woah, where am I here?” [Laughs]

So it it was unfamiliar but in a comfortable way. A new project, a cleansing of the palate.

Yeah, and I like that because that’s where songs really come from. You bust out of one thing — you might not even know why you did — and you’re in a new frame of mind and you see things differently. Maybe you get a song. Also Hawaii is a mother. More cultures have come there and been absorbed into Hawaiian culture than almost anywhere. Especially Asian cultures, so there’s a strong Asian element. I just really wanted to go there.

Well, Hawaii as a place where lots of cultures have mixed together, that reminds me of bluegrass, too — bluegrass as this thing that Bill Monroe created out of all these different traditions. So you’ve got a lot of experience exploring a type of music like that.

Very true. I think I mention something about that in the liner notes. There is one inescapable fact, which is that “Kentucky Waltz” is a direct rip off of a 1915 Hawaiian song. And the mandolin playing on that song by Johnny Almeida is exactly how Bill Monroe would play the song 30 years later.

I never knew that. Wow. So what does that say about Monroe?

What is says is a great thing. Not only was Bill keeping his cards close to his chest, which was how you’d survive in those days — it’s what you could come up with that was unique, what you could incorporate into your own song. Bill would say, “I would never steal another man’s note, but I might write one song off another,” meaning ‘I would take his melody, but I wouldn’t steal his note!’

What did he think the difference was? Writing a song off another song but not stealing?

Well, that’s a just Bill Monroe’s deception talking. [Laughs] He would steal anything he could! That was the name of the game in those days. He sang Muleskinner Blues on the Opry and got six encores, then the next week Roy Acuff releases “Muleskinner Blues” with him singing it. That galled Bill. That was like, “ooh!” But that’s how it was in those days. You just don’t let on. You’ve got to keep the surprise to your advantage. He was really competitive.

He was also really territorial about the music he created, right? Didn’t it seem like he wanted it to be carried forward in a specific way?

You mean, the way he called it “my music?” Well, yeah. But he saw me coming along and he said, “If you can learn my music, you can play any kind of music.” I thought that was saying how bluegrass gave you the foundation, which it does, but he was also talking to me as a person. I wasn’t thinking of it as a personal advice at the time, but I think he saw in me — I think he didn’t quite know what to make of me. I mean, I knew too much. I didn’t just go hide from him and then show up on stage. I sought him out. I asked questions. I came from college where they teach you how to ask questions. Plus in those days, in the 60s, it was a time of inquiry. Why are we at war? What is going on in the world? Are they really going to drop the hydrogen bomb while we’re out here on the road playing bluegrass? You just wondered, what is going on? It re-stimulated Bill in his own way. He had a renaissance at that time with these 20-year-olds in his band. He was 53 at the time. That’s when I had a lot of contact with the Stanley Brothers, who were almost from a foreign country themselves, you know, that area in Virginia.

Deep Southwest Virginia, right.

Oh my gosh, yeah. And I just cut this song about Bill taking me to see Carter Stanley. You never know why at the time, you know, but we were all still dressed up for doing our show in Knoxville. We drove up and met Carter. He was dressed in a sport coat, too, because he was going to meet Bill. That’s how it was. You never dressed down in those days. You stepped right up there and put your good shirt on, you know.

It was a sign of respect, right. I mean especially for Monroe’s generation.

Exactly. Bill hated to see anyone sloppily dressed. When I asked him what his thing was with the clothes, he told me that the people he played with when he started out were farmers who might only have one shirt, one clean shirt. So you show your respect for them by dressing up for them, and that meant something. I’ll tell you something funny. John Prine tells a story — his parents told him when the Monroe Brothers came through Paradise, Kentucky, they thought the Mafia had arrived. All these guys in their hats and suits and cases. They were like, who are these guys, moonshine emperors? Are we having a showdown? [Laughs]

So you sat with Bill Monroe and Carter Stanley while they visited. What did they talk about? What was their relationship like?

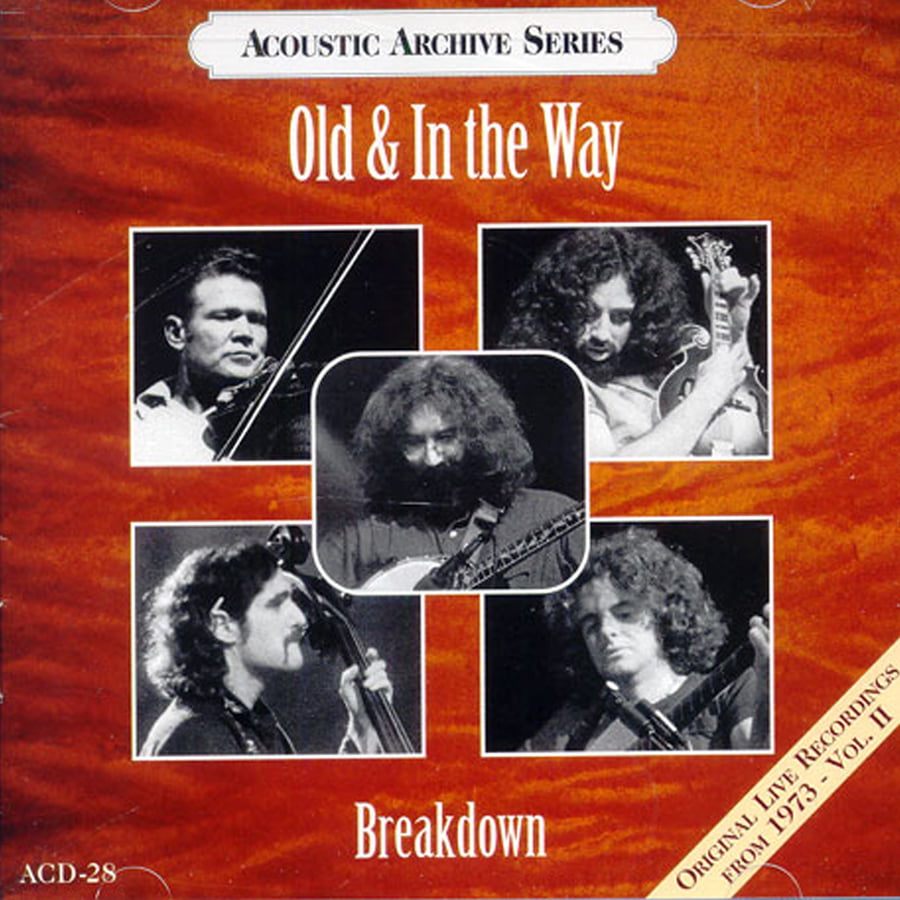

I think their relationship was very decent. In Ralph’s book he said that Carter and Bill were very close. They were close in age, you know. Close to the same age, although Carter would’ve been a little younger. I had seen the Stanley Brothers play a lot and we had been on shows together. But for me to drive Bill…it was a special break from tour, you know, before we played Knoxville that night — we had to get a car after leaving the bus in Knoxville. We drove up there I think for two reasons. I think Carter felt his mortality. Within a year he would be dead. And when I met him I was a little bit shocked. He was weak and sick and, you know, he looked jaundiced. His eyes — in my diary at the time I wrote, “I’ve looked into Carter Stanley’s tombstone eyes.” He looked bad. I think he had been diagnosed with a liver problem and he wanted to see Bill. It was an exchange where Bill tipped his hat to Carter and said that he was one of the best singers he had ever worked with. You know, Carter wrote songs and Bill wrote songs and then they both recorded their versions of the same songs. So I started thinking a lot about Carter and over the years, you know — in Old And In The Way we did “Pig In A Pen,” “White Dove,” we did “Going To The Races.” The Stanley Brothers have been the backbone of a lot of what I’ve played. It was easy to play and fun to play, but it wasn’t until I went to make these recordings recently in Nashville that I realized how Carter is a deceptive singer. To go to the five chord and sing the third, that’s not easy. To put a blue note on the third of the five, it’s like, wow, wait a second. That’s what gives this whole thing its sound!

Right. Not very intuitive. But a cool, bluesy choice, very Stanley Brothers.

It is. And it’s very strange, I could only get those notes from coming on top of them. I couldn’t come up to them. Because with Bill, you know, the music was based on a sort of fanfare [sings a mandolin intro melody], a lot of upward moving lines. Then the downward lines are the bluesy lines [sings descending blues melody]. So that’s a challenge there, to combine those two feelings. Often the verse begins with a rising line and then the end of the line descends, that kind of dying fall, that bluesy fall.

Of course Monroe had learned a lot from the blues and taken a lot from the blues, but the Stanley Brothers, too. It’s like bluegrass is a branch on the blues tree. Do you think of yourself as carrying on that tradition?

Well, yeah. And remember this, about the Stanley Brothers — the last years of their recordings were done up at King records up in Cincinnati. King Records. They had two other groups: Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, who actually did some finger poppin’ on the Stanley Brothers’ “Finger Poppin’ Time,” which was their tune. And the other guy on the label, the only label that would sign this guy, his name was James Brown. So, I mean, look where they were coming from in their musical input.

From Southwest Virginia to King Records, that’s kind of a cultural leap, too.

Well, that was on their route, their circuit, you know. Go up to the Midwest and play for all those coal miners. In Ohio there were bars everywhere. Then what started to happen was in the 60s they started to play college campuses. That changed everything. That generation became a whole enlightened generation of bluegrass followers. They now had an audience. It wasn’t just 30 coal miners in a little funky bar hidden away in rural Ohio. It wasn’t a schoolhouse. Honestly, I played the end of that era — some of those gigs were still in play, is what I’m trying to say.

You were getting into bluegrass, when was it, the early 60s?

Yeah, that was right in the boom. And strangely enough, looking back at it, within five years we had Old And In The Way going on the West Coast. In those times, being young, you’d be going from one project to another — on Elektra records with me and [David] Grisman doing Earth Opera, out in LA doing Muleskinner for Warner Brothers. It was fast moving, and there weren’t many of us! I mean, there weren’t 150 bluegrass players on the planet. There were twenty-five. So, you know, you could have something different to offer for a musical project. But what I didn’t really understand was how to bring out the bluegrass. We did a little bit of that in Sea Train. We did Orange Blossom Special and Sally Goodin because they were crowd pleasers. But every time I tried to sing a bluegrass song it was shot down. These guys, they were from New York. They knew Blues, but maybe I couldn’t be convincing enough to do anything as lonesome as what came out of bluegrass. We got into that on Muleskinner after that period with Sea Train. Then with Old And In The Way we just went for it! With Jerry Garcia on our side, thank you very much. You know, ‘Call up Vassar Clements and let’s go!’ Jerry just wanted to play the grass. I think his version of White Dove is the most stirring.

Really? Interesting to think of Jerry’s version of bluegrass as getting to the heart of it, compared to The Stanleys. I guess you’re the only one who played with both of them…

Well, you know, when I sang White Dove with Ralph it was like, oh, surprise, we don’t do White Dove slow in this band — they would swing it. The mountain people, if they’re going to dwell on stuff, it’s going to be right to the cradle and grave. But when it gets down to the uplift of bluegrass, they weren’t trying to do it as art. They did it as a lifeforce support system. So there’s all these uptempo melodies, and even a waltz would be kind of bouncy. Bill, you know, had been to New Orleans. He had heard New Orleans music. Arnold Shultz, his black blues guitar partner, was from New Orleans.

Did you ever talk to Bill about Arnold Shultz?

I did, yeah. I talked to him about New Orleans, too. He said the first time he had his own band they went down to New Orleans and stayed for two months. So I said, “What kind of music did you hear there?” And he said, “A man could hear any kind of music at that time.” That would’ve been the 40s.

Would that have been with Charlie [Monroe], or with the early Bluegrass Boys?

Well, maybe ’48. That’s what I had in my diary, that it was with Flatt and Scruggs. That was sort of where he took them to train them. I don’t know, but that’s what he told me, so that’s what I wrote down. What he said was, in those days you had the sock time — think “True Life Blues” — you had jump time, and of course you had ragtime. And, he said, and then you have the slow drag. [Laughs] It’s a slow 4/4. So what Bill did was sped it up, kept the sock time in there, and if you want to think of the slow drag translated into Bill’s particular take, think of “Blue Moon Of Kentucky,” the original recording. Or “In The Pines.” These were musical genres within the blues of New Orleans.

Did you write down a lot of what Monroe told you?

I would keep a diary the whole time and listen to him talk. You know, we’d be riding along in the bus, a little disjointed, bouncing around, and he’s playing on the mandolin. He’d say, “That there comes from American Indian peoples.” Then he’d play something else and say, “Now that comes from New Orleans.” I was like, New Orleans? And he said, “Yes, sir.”

Photo credit: Amanda Rowan