Hitting play on singer-songwriter Madi Diaz’s latest album, Fatal Optimist, one wouldn’t automatically identify her close-to-the-mic, chunky strums and anxious, confident vocals as “metal.” But keep listening and trust.

Fatal Optimist is heavy on numerous elements of metal – fantasy, humor, darkness, anger. For much of its runtime, it feels like the inside of a clenched fist, slowly but surely letting go. With songs that are, this time, centered around her solo voice and acoustic guitar, Diaz turns her liminal songwriting further inward than ever. This is saying a lot for an artist who’s no stranger to personal narrative. While her prior album, 2023’s Weird Faith, brushed up against hopeful optimism, this follow-up proves that earned optimism is perhaps the better version.

After all, Diaz chose to open the disc with the wordplay stunner “Hope Less,” a stiff shot of reality that reorients us to a heart at least as full of darkness as light. If the LP’s vibe is “clenched fist,” its songs play like spokes in a wheel rolling us toward the jubilant title track – a progression Diaz admitted in our recent BGS interview was equal parts intentional and inevitable.

This album starts out very quiet. It feels very close and very intimate, then it slowly opens up. Was that the intentional vibe and arc of the album for you?

Madi Diaz: It definitely ended up being a much more lean-in [kind of] record. The further I got down the road, the more it felt very obvious that was just what the song content needed. It’s kind of heavy stuff, I think. It was a lot of mining of the self, which I did a lot privately. So I felt like I wanted the songs to match that [vibe], in the end.

I was listening to it this morning, thinking about your song “Everything Almost” from the last record. Like, how optimistic and full of hope that song is and then this album starts off with a line like “hope less.” Obviously, when you’re writing about personal events in your own life, it’s easy to see connection in the rearview. But I’m wondering if there’s something more to what feels, to me, like a connection between that song and this project.

That’s funny. I was just talking about this. I do feel like a lot of the songs in the last record … are about following that gut intuition. That gut feeling. So a lot of the songs on Weird Faith are absolutely going like, “I think this is it. I think this is gonna work. I think we’re really gonna get there.”

There was a really funny moment I had recently. I was practicing for this tour and putting [together] the set list. I wrote this song called “This Is How a Woman Leaves” for my friend Maren Morris, her last record that she put out [Dreamsicle, 2025]. I am planning on releasing a version … at some point down the road a little bit. But I was practicing “Everything Almost” and then I wanted to go into “This Is How” because in “Everything Almost,” I’m packing the boxes and moving in. In “This Is How” I’m fucking moving out.

Like, “How it started, how it’s going.”

It’s the “fuck around and find out” journey right there, in a nutshell.

Nice. I was reading that you went to an island when you were writing the album. Can I ask what island you went to? And did you know that’s what you were going to do when you started your trip to that island, planning, like, “I’m gonna get it together.” Or was it just kind of like how life happens?

There were, actually, many islands. Physically, mentally. … I started off coming off of this European tour. We finished this tour in Italy, so I went to an island off the coast of Italy and was there by myself. I did a lot of journaling and walking – so much walking. I’m a big processor by walking and talking, so I would kind of record myself as I was processing things out loud. I really wanted to be in a space where I felt safe to do that. It felt like the safest thing was to just take myself away from everybody, so as to not barrage people with [my feelings].

I started off in Ischia and then I ended up, really wonderfully, being asked to be a part of this [songwriters’] colony in Nantucket. So I did that. I ended up going to Long Island with my dad, to Noyack, and just [did] a lot of journaling there.

Also, [I was] feeling very much like I couldn’t tell whether I was the island or the island was the island. It was just this very unescapable lonerism. Solo mission, you know. Like in a spacesuit, kind of feeling. I just couldn’t shake it, so I just took it with me everywhere I went.

Can you talk a little bit about the process of songwriting? Your songs are so personal, almost uncomfortably so. I wonder if that’s the result of writing in an actual journal on paper and if that’s a different kind of creative experience for you than voice memos on your phone, which so many people do now instead of journaling.

I definitely rely on journaling still. A lot. Sometimes, if I’m in a pinch, I’ll text myself an idea. Or, I have [the] Notes app open. A lot of Fatal Optimist was pulled from about a year’s worth of pretty serious journaling and going back over certain words that kind of stuck out. I love journaling. I think it’s like a life scrapbook, you know? There’s a funny thing that happens. Sometimes I’ll open a journal and I don’t even know what year it’s from, because some of the issues [are] so consistent. … But it’s kind of like a sweet reminder, of survival, I guess.

Totally. Do you remember writing the couplet at the beginning of “Lone Wolf”? “Lamb’s gotta lamb, god planned it/ Wolf’s gotta wolf, goddamn it.” It’s such a perfect little song, but it doesn’t feel trope-y. It feels, really, like a strike of inspiration.

Well, I remember it was dead of winter. I was sitting on my couch with Stephen Wilson Jr. and I was going through my journal. I was talking about what was on my heart that felt so difficult, about reaching this person who chose to be a loner. I mean, he literally said to me, “I’m a loner. I’m a lone wolf kind of guy.” And I [thought,] “You just said that. That’s ridiculous.” Like, have you not seen the Pee-wee Herman movie where he’s like, “I’m a loner, Dottie. A rebel!”

But it was this thing, you know, that I almost didn’t take seriously, because it was such a crazy thing to say. And I should have [believed him], obviously, because here we are. I was talking to Stephen about it and we were laughing about this wolf character and the lines just fell out. In the aftermath of it, it’s funny.

You know, when you push somebody that wants to be alone away, they tend to want to be less alone. They feel very confronted. I mean, I’ve been there. All of a sudden, you’re confronted with your loneliness and wishing that you actually had that connection. So, when I pushed him away initially, he would just kind of show up and stick around. I really wanted him to leave me alone. Damn it. “Goddamn it” definitely came from that.

The lyric on that song is so simple. You don’t go into a lot of poetry, you don’t go into a lot of storytelling. The wolf keeps showing back up, looking good, trying to get back in. Can you talk a little bit about trusting yourself to keep it so simple? Does that come from editing or did it just feel like that’s what the song was?

I try to say it in a way like we were just talking about it sitting in the bar. I’m trying to not be misunderstood. I’m trying not to feel misunderstood even to myself. So I think I try to keep it clear and cutting, and [the way] it comes out. If it’s possible to get even closer to it, I’ll edit, but I don’t really edit a lot.

Oh wow. So it just comes out that way. That’s impressive.

Sometimes it does just come out that way. Not all the time, but sometimes it mostly does.

The other line on this album that I really wanted to unpack is in “Heavy Metal.” The line is, “In some religions, repetition is spiritual.” I wanted to unpack it a little bit, because music is often a place where people will repeat words or phrases, for a whole bunch of reasons.

But that line made me really listen to the words and phrases you were repeating elsewhere on this album: “Whose move is it to move on.” “I always love you.” “God knows how long.” “Ambivalence.” Can you tell me a little bit about how you decide what to repeat? Is it a conscious choice or just part of the process?

I think when I’m repeating something, it’s because it feels different on every lap. I’ll repeat something when the feeling is lingering in a way that– maybe if I say it enough, some magic spell will break and I’ll be released by this thing. Sometimes I feel like the repetition of it comes from a bit of a desperate [place] like, “Just get it out of me.” Maybe if I do this ten times, I’ll never have to do this ever again, which is why the [line,] “In some religions, repetition is spiritual.” …

You’re always going to carry it with you. You can learn how to hold this. I can learn how to learn from it differently every time, you know.

I guess that’s why repeating “ambivalence” is really interesting to me, because it seems like repeating that particular word is a contradiction.

I guess that’s true. Ambivalence means “caught in the middle.” Feeling in so many different directions. For me, ambivalence feels like a very desperate feeling. It almost feels like it should come with a bit of an alarm bell. Like, “Oh God. I’m feeling all of the feelings at the same time and I don’t know which one to choose.”

That makes sense. The other thing in the song “Heavy Metal” – I wanted to ask about your mom. I feel like you have mentioned your parents in other songs on other albums. But this made me wonder about your relationship with your parents. Somehow, I don’t think people talk about their parents much in music. I can’t figure out why. Do you have any thoughts on that?

I think it’s scary. It’s so scary. When I know a song is about me, I definitely tend to listen with a microscope. No one is trying to hurt anyone, but we’re all really trying our best to process love, pain, joy. I don’t know. Our effect on each other. What’s mine, what’s yours. So yeah, it’s not an easy thing to write about. …

I feel like I’ve felt the most loved and I’ve felt the most hurt by both of my parents. I think that that’s pretty normal. Or maybe not? Maybe it’s not normal.

I think it’s pretty universal.

It always kind of ends up that way. The people closest to you hurt you the most, which is why you really have to trust the people closest to you. So that when they do hurt you, you can [heal].

I think “Heavy Metal” felt right to start you talking about my mom, because she’s kind of a badass and kind of a hardass. In all the best ways and all of the hardest ways. There are some things about being tough and resilient that I wouldn’t trade for the world. It helps me survive in so many corners of my life. But also, I’ve had to really undo some of the damage that being tough does. You start to weaponize that toughness against yourself and others in a way that I didn’t even know I was doing for a long time.

Then [again,] you just don’t want to piss them off because you also want to be able to go home for Thanksgiving and stuff.

Right. That’s what makes it such a metal move, you know, to comment on your mother in this way. I’m assuming she’s still alive. Has she heard the song? Does she have any feedback for you?

I haven’t heard [feedback] yet. I really don’t know. But I’m so grateful to my mom for raising me the way that she did and giving me and my brother the lives that she gave us. I feel so lucky that she’s my mom. It’s hard to have a song like this. … But that’s just fucking art, man. It’s so hard, at the end of the day. You know, we can make it as personal as it is or as just-about-me as it is.

The last thing I want to ask about is the song “Fatal Optimist,” which is sort of a sonic departure from the rest of the album even though it’s obviously very on-topic. As a listener, it feels like we just went on this long, arduous, emotional journey, and now we’re suddenly above the tree line and the drums are here and everybody’s in the room. Not to get too nerdy about sequencing and stuff, but was there any world in which that song could have been anywhere else on the album?

It would have been a nice break, wouldn’t it have been? I just couldn’t do that. I couldn’t interrupt the intensity of this record.

I do know that optimism is a soothing balm. When it hits you, it just hits you. There’s no explanation for it. And I knew that, for me, I want a reason to listen to a record again. … This whole record feels like one step after the other. It’s like my attempt at a gift or something [for] going through it. Hopefully, these [songs] can all be like little lights on the path that lead the way to this finish line of fatal optimism. Then we can run it all back again.

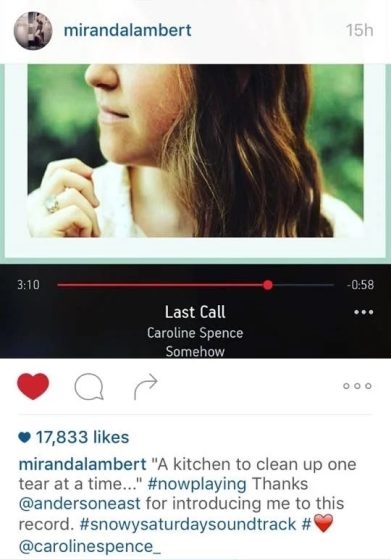

Photo Credit: Allister Ann