Lee Ann Womack had to get out of Nashville to make what she calls a real country music record. Specifically, she had to get about 800 miles away. For her eighth — and maybe her best — album, The Lonely, the Lonesome & the Gone, Womack trekked down to Houston, Texas, and set up camp at the historic SugarHill Studio, which has hosted famed sessions by some of her musical heroes: Lightnin’ Hopkins, the Sir Douglas Quintet, George Jones, and many others. Nashville has plenty of similarly legendary rooms, of course, but Womack needed to get away from the grinding gears of the country music machine — what she derides as “McRecords.”

“It’s like a factory,” she says. “What was great about being down there in Texas is that you’re in a studio where people go to work everyday and you have all kinds of music being recorded there. Nobody’s going in thinking, ‘We’ve got to lay down a three-minute uptempo love song for radio.’ They’re not thinking about how we’re going to make the most money out of three minutes of music. All they’re thinking about is going in and making great music.”

Womack is one of the few artists who can drop a phrase like “real country music” into conversation without sounding defensive, dismissive, or derisive — in other words, without buying into received notions of authenticity. Her definition of “real” is deeply personal and based on the country music that was popular 40 or 50 or even 60 years ago, but Lonely proves that even old tunes and old sounds can speak to this modern moment. Rather than restrictive, the term becomes freeing: These new songs range from the stately countrypolitan of “Hollywood” to the gritty blues of “All the Trouble,” from the beautiful reimagining of the 1959 Lefty Frizzell “Long Black Veil” to the remarkable insights of the title track, a country song about country songs.

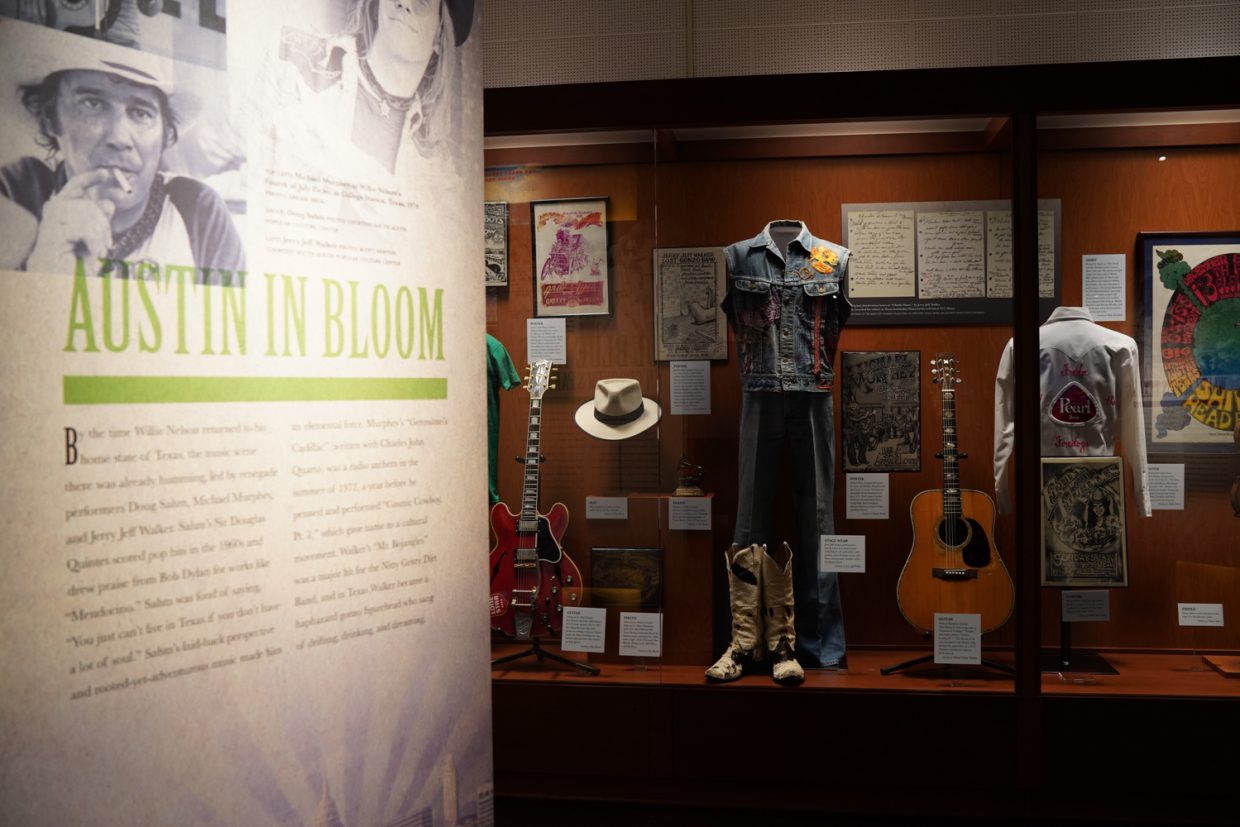

Recording in Houston actually brought her closer to some of her Nashville heroes. Womack grew up in a small town called Jacksonville, Texas, about three hours due north of Houston. Her father was a country radio DJ, a profession that provided his daughter with a deep grounding in the music’s history. As a child, she loved Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys. “I thought he was funny. The music was upbeat and bouncy, which any kid would like, and then you’ve got this guy talking all over the tracks: [Imitating Wills’ falsetto] ‘Shoot low, sheriff! I think he’s riding a Shetland!’” She might have been laughing at the bandleader’s antics, but she was subconsciously absorbing the complex horns and fiddles. “It becomes part of the fabric of your musical DNA.”

As she grew up, Womack raided her parents’ record collection, which was full of albums by Ray Price, George Jones, Porter Waggoner, Dolly Parton, and, of course, Willie Nelson. “Twin fiddles and steel guitar and story songs — these were the things that I thought were country music, and I thought my idea of country music was everybody’s idea of country music.” Ironically, being in Nashville only distanced Womack from her first loves. “Growing up in East Texas, I was full of dreams and hope. Then I moved to Nashville and, after 20 years, you get kind of jaded. Things change,” she says. “Every time I go back home, I have a spark of that feeling I had growing up. I wanted that again. I haven’t made a record in that frame of mind in so long. I just wanted to be surrounded again by the things that shaped me growing up.”

All of those old sounds inform the new record, which was produced by her husband, Frank Liddell, and finds Womack moving even further away from the country mainstream. Disregarding the need for radio airplay and signing with ATO Records [home to the Drive-By Truckers and Hurray for the Riff Raff] suggests she is cementing her place within the Americana market, adopting a rootsier sound for a very different kind of audience. As she recounts her career, however, Womack insists she has always gravitated toward this kind of music, even when she was just starting out. “When I walked into the offices of Decca Records to audition, I walked in with just an upright bass, myself, and an acoustic guitar. We played as a trio, right there in the office,” she recounts. “And that’s exactly who I was. My first record had a song on it called ‘Never Again, Again,’ and that was stone-cold country. Even in 1997, I felt like I needed to remind people of what country music really was.”

And yet, within the country sphere and without, she is best known for 2000’s smash single, “I Hope You Dance,” which achieved the crossover success so many Nashville artists covet. Recorded with Sons of the Desert, it’s a slick and sentimental pop-country anthem whose uplifting lyrics could double as a graduation speech or a Hallmark card: “I hope you still feel small, when you stand beside the ocean. Whenever one door closes, I hope one more opens.”

To her credit, Womack doesn’t ignore or disregard her biggest hit, no matter that it is something of an outlier in her catalog. She still performs it at almost every concert, still sings it like it’s a brand-new song, still invests those lyrics with sincerity and immense generosity, even as she strips it down to its core. “Those lyrics still stand up with just an acoustic guitar,” she says. “I might have cut a couple of lightweight pieces along the way, but I tried to cut the best songs I could find. And now when I go out and play with fewer musicians in a more stripped-down setting, those songs hold up because they were great songs to begin with. I guess a lot of shit got put on them to make them more commercial.”

That is perhaps one of Womack’s most undervalued talents: She is a sensitive and intuitive song collector with a discerning ear for complex sentiments, sturdy melodies, and relatable characters. On her last album, 2014’s The Way I’m Livin’, she covered the Texas singer/songwriter Hayes Carll and managed to outdo Neil Young on her tender version of “Out on a Weekend.” Lonely includes a handful of old-school covers, but the standouts are those penned by young scribes like Brent Cobb, Adam Wright, and Jay Knowles.

During the sessions in Houston, there were discussions about the title track, which includes the line, “[Hank Williams] never wrote about watching a Camry pulling out of a crowded apartment parking lot.” According to Wright, who co-wrote the tune, “Some people were like, ‘Camry isn’t very cool. Is there another car we can use?’ But Lee Ann said, ‘No, it’s a Camry. Those are the lyrics and that’s what it is.’ And that’s the point, after all. It’s not a Jaguar. It’s not a cool car. It’s not romantic.” As she sings it, that is one of the most arresting lines in a song this year — country or otherwise — and she delivers it with a gentle despair and even a little resignation, as though measuring the romance of an old country song and the reality of everyday life. “The care she takes with these songs left a big impression on me,” says Wright.

For Womack, country music is real when it’s about real people — not just the musicians who write and sing the songs, but the listeners who play those tunes over and over again, who hear their own dreams and hopes echoed back to them. “I have this theme about myself and about others,” says Womack. “I don’t know how else to describe it, except to say that I am drawn to losers. I hate to call anybody a loser, but I throw myself in that pile.”

By “losers,” she means people facing down challenges bigger than they are, and that accounts for just about everybody on earth. “That’s why I’m drawn to songs like ‘All the Trouble’ and ‘I Hope You Dance.’ They’re about challenges, about hard moments in life,” she muses. “There was a time when country music spoke more to those types of people. Now it’s speaking to a different group of people. That’s fine, but I want to speak to the challenges of life. The lonely, the lonesome, and the gone? Those are my people.”

Lede illustration by Cat Ferraz.