Tag: Noam Pikelny

Punch Brothers Explain What Hasn’t Changed

The Bluegrass Situation interviewed all five members of Punch Brothers upon the release of their compelling new album, All Ashore. At the end of the individual interviews, we asked each member just one question that overlapped: “So much has changed in the music world – and even in your band’s musical evolution – over the last ten years. But what would you say has stayed the same between that first record and now?”

As one would expect from Punch Brothers – who are nominated for IBMA Instrumental Group of the Year – every member offered an interesting perspective. (Read the other interviews here.)

Gabe Witcher: “The thing that’s stayed the same is, I think, the level of excitement we all have, still, just to play music with each other. And the shared wish to keep exploring what this ensemble can do, and to keep reaching for new things. Making new discoveries. Finding new sounds. Everyone is so super committed to that on their own, but also, once we get together, it’s kind of a miracle in a way. This kind of spontaneous and natural thing that happens when new, exciting things keep popping up. Like, ‘Oh my God, that’s awesome! What is that? Remember that, save that. Let’s use that. Let’s figure out what that is.’ That has never gone away. And I think that as long as that thing’s there, we’ll continue to make music.”

Chris Eldridge: “To me, in a way it’s all the same and it’s all different. I feel like we’re doing now what we were doing then, and in a way, it doesn’t feel so different to me in terms of how we want to work on our music. … I feel like consistently from then until now, there has been a real sense of wanting to be a band. I think that’s kind of the thing. Whatever is cool about the Three Musketeers – all for one, one for all – that from the get-go was the thing and still very much is a thing.

“Everybody is playing pretty selflessly in Punch Brothers and everybody really just wants the music to be good. At the end of the day, that’s the overriding thing that’s what brought us together as people, that’s what keeps us together as people, as musicians. We all just really love music and we share a common vision about how it should be and what it can be.

“Even as people have different ideas to move things forward, most notably Thile, there’s always been a real shared sense of purpose in this band. It should be that way for any band, but somehow, sometimes, I don’t think it is. And I think that’s been one of the things that has really contributed to us still wanting to make music together and working hard on it when we do. We just love music and we always have.”

Paul Kowert: “So, we live in the most politically tumultuous time of our lifetimes. We’re in our mid-30s, that’s a big change. Among the bandmates, three of us are married and two of them have kids, so that’s a huge change. I mean, that influences the tour schedule a little bit. Besides that, I don’t know what’s really different, you know? I mean we’re just making more music.”

Noam Pikelny: “I think everyone in the band genuinely likes each other. That’s like a rare thing. Paul is in the corner, shaking his head. (laughs). But we genuinely like each other as human beings and I think we really respect each other musically. So there’s this real sense of responsibility to each other to keep this as part of our musical lives. To me that’s a beautiful thing, that this is something that we can keep coming back to over the years. It doesn’t always have to be the main project. It could go dark for a couple of years while people are doing other things, it could come back. And it feels like not that much time has passed.

“The reason we decided to transition from just an album [Thile’s 2006 project, How to Grow a Woman From the Ground] into a band is probably the same reason why we’re still making music together right now. It’s artistically rewarding and I think we decided to keep doing this beyond the first album because we felt we were just scratching the surface of what was possible. … And 12 years later, I still have this sense of, ‘Well, we’re just scratching the surface, so we’re gonna keep doing it.’ There’s still more we want to uncover.”

Chris Thile: “We love making music with each other. We crave making music with each other. When we are in the midst of other projects, no matter how much we are enjoying those other projects, there is always this feeling, like, ‘I can’t wait to get back with my boys and see what they think about this….’ I think that a mutual love and respect has resulted in a partnership that will last until one of us dies.”

Photo credit: Josh Goleman

Artist of the Month: Punch Brothers

To celebrate our Artists of the Month and their brand new album, All Ashore, we interviewed each individual member of the Punch Brothers, exploring the processes, circumstances, and factors that led to the creation of this latest crop of songs. The themes and responses are just as diverse as the five men themselves and their musical approaches.

Gabe Witcher, the fiddle player – and some might say secret weapon – in Punch Brothers, has been a performer for nearly his whole life. As a kid, he toured the Southwest playing bluegrass with his family’s band; that’s how he met Chris Thile, forming a musical friendship that has spanned more than three decades. Though his stage presence is low-key, his musicianship is undeniable, playing as joyously or mournfully as a song requires. This is also true on All Ashore. [Read Gabe’s interview]

Paul Kowert came on board as bassist for the Punch Brother about 10 years ago, stepping into a band of musicians he knew casually but admired greatly. In the following decade, he’s gained even more visibility in the world of acoustic music through his band Hawktail and a gig as bassist for David Rawlings Machine. His versatility is reflected in the list of bassists he cites as influences: Edgar Meyer, Mark Schatz, and Roy Milton “Junior” Huskey. He’s quick to admit that he’s not a lyricist, yet his musical contributions definitely shape the undercurrent of the new record. [Read Paul’s interview]

Chris Eldridge, the good-natured guitarist for Punch Brothers, comes by his bluegrass pedigree honestly. As a young man, he attended innumerable shows by Seldom Scene, a pioneering ensemble whose lineup included his father, banjo player Ben Eldridge. After studying at Oberlin Conservatory, he co-founded the Infamous Stringdusters, which won three IBMA Awards following their 2007 debut project, Fork in the Road. Indeed that album title proved auspicious, as Eldridge took a different path with the formation of Punch Brothers – a rewarding partnership that a decade later has yielded their newest project. [Read Chris’s interview]

Noam Pikelny has a dry delivery only when he’s joking around. But as the banjo player in Punch Brothers, his playing is crisp, inventive, and in step with his colleagues. This is especially true on All Ashore, which explores the personal challenges of relationships as well as the growing political divide in America. This year he’s nominated for IBMA Banjo Player of the Year, while his two previous solo albums earned Grammy nominations. His Twitter bio sums it up: “Widely considered the world’s premier color blind banjoist. Punch Brother.” [Read Noam’s interview]

Chris Thile is walking briskly into the venue while chatting agreeably about Punch Brothers’ new album. He’s used to multi-tasking, of course. In addition to kicking off an extensive tour with that eclectic band, he hosts the public radio show Live From Here, and he’s also a husband and father with a lot on his mind – particularly when it comes to the state of the world. [Read Chris’s interview]

Illustrations by Zachary Johnson

Punch Brothers’ Noam Pikelny: Getting Inside the Story

Noam Pikelny has a dry delivery only when he’s joking around. But as banjo player in Punch Brothers, his playing is crisp, inventive, and in step with his colleagues. This is especially true on All Ashore, a new release that explores the personal challenges of relationships as well as the growing political divide in America. This year he’s nominated for IBMA Banjo Player of the Year, while his two previous solo albums earned Grammy nominations. His Twitter bio sums it up: “Widely considered the world’s premier color blind banjoist. Punch Brother.”

This interview is the fourth of five installments as the Bluegrass Situation salutes the Artist of the Month: Punch Brothers.

When I was at your show at the Ryman, you were usually turned toward the band but I could never tell if you were singing. Do you sing with the guys on the songs?

I sing on a few things, but not much on this record. I actually don’t think I sing any harmony on this record.

Is that by choice or have they tried to convince you otherwise? Why is that?

Usually, like when I’m singing at all, it’s because we have like five part harmony going on. And I think it has to do with my range. I have the most limited vocal range of anybody in the band. But that was how I was born. I was born that way, it’s not my fault! … And then on the one song I sang on, on the last record, they invited everybody else in the universe to sing on it. On the song “Little Lights” that was on The Phosphorescent Blues. And so I think it essentially the policy that if Noam is allowed to sing, then everybody is allowed to sing. It’s only fair to have a one-hundred person overdub. I can’t hear myself because of all these people.

A couple of you have mentioned what’s going on in the country right now as inspiration. I think it’s on everyone’s mind, but why does it seem like a good inspiration for a song? Like “Jumbo,” for example. Why do you think it lent itself to writing a song?

Well, I think on a more macro level, I think it’s really important to be sticking to your guns. I think a lot of people are demoralized and questioning whether what they’re creating or what they’re doing for a living is valid in times when it seems like a lot of them are under assault. I know for me personally that having an opportunity to make music with musical co-patriots was very crucial. I feel like there’s such division right now in this country. I think people are thriving on families being alienated from each other. You think of the Thanksgiving dinner that becomes so troublesome. Friends are becoming alienated through all kinds of political differences and I feel like our sense of community and our sense of comradery as a whole is kind of under assault.

I think parsing through what’s going on in our lives right now, a solo project can be quite lonely. I think we find strength in working with each other and we have the ability to hone our thoughts with each other around, as far as what’s important to us and what we want to say. For “Jumbo” in particular, why does this make for good music? Or why is this musical inspiration? I ultimately thought that these people are like the protagonists that are Jumbo and his cohorts, they spend most of their time celebrating themselves. And we just wanted to get in on the action and celebrate them as well. So it’s really a celebration, more than anything.

It’s a fun melody if you just listen at the surface level. How’s it going over live? It seems like one that people would be responding to?

I think people are responding to a lot of it. [Playing live] is a huge component of the musical journey of this music. Making a record is obviously the most concrete and typical manifestations of the music. But the journey really is just beginning once that’s finished and we start playing it live, getting audience feedback, and shaping the song for the live experience. We’re flattered that people are enjoying it and starting to know the words.

Gabe that told me that you have a good story from being on Letterman. Do you have a minute to tell that story?

Oh, I’m not sure exactly what he’s referring to. I mean we got to go on Letterman about eight to nine years ago and play with Steve Martin. He announced that he was doing this yearly banjo award – it seems like a long time ago, it was nine years ago now. So, it was one of the more surreal experiences of a lifetime, getting to be up there with Steve Martin and Dave Letterman.

You were the first one to get that award. I remember when that started. Since then, a lot of your peers have been recognized. This sounds like a weird question, but is there like a banjo community or like an instant friendship when you meet another banjo player?

Um, there’s a secret banjo cult that meets in a cave in Horse Mouth, Kentucky, on the third Saturday of every month. And everyone’s totally cloaked and in these robes that are covered in banjo tablature… No, there’s no secret society – or if there is, I haven’t been invited yet which probably makes sense. But I think there’s an instant kinship with anybody else who’s pursuing music as their life’s work. And I think any instrumentalist, you always want to pow-wow and talk about their techniques and who they studied with, so I think there’s an extension in that way.

I wanted to ask you about songwriting collaboration. The way I understand is that everybody wrote the music together and then crafted the stories on top of the music. Is that pretty accurate? What was the process like?

We write the music instrumentally first, as a band, and that’s often with the five of us in the room. Oftentimes, Thile will be kind of singing, just gibberish, or a few words he has stuck in his head that associates with that music. Sometimes, those couple words will become the kernel of the song, and we’ll shape it around that. He often goes off and starts writing lyrics and brings it back for collective input, and we’ll help edit and shape the lyrics.

Sometimes we’ll have late-night discussions over cocktails or a drink, talking about what’s going on in our lives, whether it’s our familial environment or what’s going on in the world right now, and he’ll go off and try to capture that collective thought into a lyric. So it’s always different, but interestingly in Punch Brothers, the lyrics almost always come last. We write placeholder lyrics first, then that’s the final but obviously very crucial element.

Are you a good lyricist? Do you enjoy contributing in that way?

I don’t consider myself a true lyricist. I really do enjoy the process of working with the lyricist. And I feel it’s an effective kind of partnership to them to have Thile leading the charge in that way, but then having this kind of counsel for feedback that can be brutally honest.

You just got married this year right?

Correct. A few months ago.

So this album has a song like “All Ashore,” which is about a relationship falling apart, but then you’re a newlywed. In order to get into a character, do you have to set your personal life out of mind when you perform a song like that? How do you separate the two?

Well, no, I think “All Ashore” isn’t about the collapse. It’s more about the challenges. It’s the struggle and the ups and downs, the ebb and flow, to quote the song itself. But you know, when we get up and play a song like “Molly and Tenbrooks,” which is a racehorse song, I don’t feel like I have to identify personally with the jockeys or the horses … but I think it’s really important to get inside the story of the song and as you perform it, you can really deliver the intent of it.

And so there might be a difference of whoever is the lead singer. You’d have to ask Chris how it’s different, whether it’s sung from the first person, or a narrator, or an actor. All of those roles probably come into play on different material and especially on covers that we do. … I think you can emphasis the story even if you don’t see yourself in that story. That’s the case in music and in real life. I think being an instrumentalist, I’m trying to support the singer by helping him deliver the intent of the song. I make the story more vivid through the way that I play it.

Illustration: Zachary Johnson

Hangin’ & Sangin’: Caitlin Canty

From the Bluegrass Situation and WMOT Roots Radio, it’s Hangin’ & Sangin’ with your host, BGS editor Kelly McCartney. Every week Hangin’ & Sangin’ offers up casual conversation and acoustic performances by some of your favorite roots artists. From bluegrass to folk, country, blues, and Americana, we stand at the intersection of modern roots music and old time traditions bringing you roots culture — redefined.

With me today in the Writers’ Rooms at the Hutton … Caitlin Canty.

Hello!

I’m glad you’re here!

Me, too!

You have a new record, Motel Bouquet.

That is correct.

It’s your third record.

Yes.

We’ve hung out, but I’ve never actually gotten to interview you, so I have some questions.

Fire away.

…

The record, Motel Bouquet, produced by Noam Pikelny.

That’s right.

It’s such a dreamy record. The first time I listened to it was a snow day, and it was perfect … although listening to it on an allegedly spring day also works. But the pedal steel, the strings, the banjo, this web of dreaminess under your dreamy voice and your lovely songs. Let me ask, though, did you have trouble finding a decent banjo player? [Laughs] Because I know those are in short supply.

[Laughs] I started working on Noam with these … we played a couple shows together, and he and I had written two songs that are on this record. I’ve never worked with a producer I’d written with. He had already brought his ideas, when we’d played as a duo, he’d brought his thoughts to the table. So we went into the studio one day with some folks to catch one song, and we got three others that day, and it was so much fun and it felt so good that we booked two more days. That’s how this came together.

Because it came together really quickly.

Ooh, no.

Almost too quickly?

No! [Laughs]

Well, I mean the recording!

When I walked through the studio doors on that first day, everything since then has felt easy and fun and right and natural, like I won the lottery. The people I played with on the record … for people who aren’t scrolling through my press release right now … Stuart Duncan played fiddle, Jerry Roe played drums, Russ Paul played pedal steel, Noam played electric guitar, Paul Kowert played upright bass. That was the core band, and me and my Recording King. We were at Josh Grange’s studio in town, and it felt so good. We also got some backing vocals from my favorite singer on the planet, Aoife O’Donovan. Gabe Witcher also played some fiddle while they were on tour with Noam, weeks after we cut this. So the core thing was live in the room.

And with that limited time, you have to have the best of the best, and everyone has to walk in ready to go. The songs have to be solid — you can’t be sitting in the corner finishing the chorus.

No, we had charts and had thought through the arrangements. The folks who were coming to the table, they are those musicians who can turn on a dime and they are folks who have their own sound, their own ideas. What really struck me about this recording, more than a lot of situations I’ve been in was, when you have people with such strong personalities, but there’s no ego involved. That’s a really interesting balance, and I feel really lucky to have that — when people can bring their own thing, but also be supportive of the song and can put the voice in front. They have an idea of what they want to bring, but not step on the toes of another person.

They’re still there to serve the song.

It’s amazing. It was so fun. I wish it took 100 days to record! [Laughs] But the pre-roll, the reason I was rolling my eyes about it only taking three days was, before took so long! Constant editing and writing new stuff.

So you guys mapped it out pretty tightly going in, knowing that you were gonna be limited.

Yeah, and some of these songs I’d played.

You’d road tested them for a while.

Yes, and some were brand new — I’d never played them with anyone before. It was a good mix of the tried and true that had never found their sound, their place yet on an EP or the band hadn’t hit that sweet spot yet. It was just … I wish you could have been there!

I wasn’t invited, Caitlin, or I would’ve stopped by! [Laughs] What’s interesting to me, in listening to it, because I’m still somebody who listens to a record all the way through, a whole piece.

Thank you. Me, too.

And there are a lot of different things going on style-wise, but it’s still very cohesive as a piece. What do you think’s the magic there, the glue? It’s not just your voice.

Certainly not that. I think it’s the programming of this as only a handful of days means that you’re in the same mindset, you’re in the same time and place. You have the same people involved so they can see what we’re doing. It’s not like you just walk into a scenario and you leave it and hear about it three years later. They were the band.

Or you weren’t jumping around to different studios with different players, something like that.

I think the glue is when people can share that moment together. I almost feel like, when you’re in a van on tour, there’s an overlapping of our thoughts, in a way. Once you start eating together and hanging with each other, there’s just something that happens.

Watch all the episodes on YouTube, or download and subscribe to the Hangin’ & Sangin’ podcast and other BGS programs every week via iTunes, Spotify, Podbean, or your favorite podcast platform.

Photo credit: David McClister

The Producers: Gabe Witcher

Gabe Witcher has a superstition about shutterbugs in recording sessions. “I’m a strong believer that all photos that come out of the studio must be in black and white. Color photography is too real. It loses mystery to me. Black and white has enough fantasy in it, where you can use your imagination to create the world that existed at the time the recording was captured.”

It is, he admits, a “weird little thing that I think about,” but he’s not wrong. Most iconic music photos — whether it’s Paul Simon smashing his bass onstage or Johnny Cash furiously flipping the bird — need no other hues beyond black and white. Anything else is a distraction: too flagrant, too revealing, too matter-of-fact. Witcher would rather let the creative process retain some sense of fantasy and wonder.

Thirty years into his career, he has yet to tire of the mystery. Something like a child prodigy on the fiddle, he paid his dues in the Southern California bluegrass scene, appearing on Star Search in the 1980s before joining Herb Pederson’s band, the Laurel Canyon Ramblers, as a teenager. Witcher has recorded with Béla Fleck, Dave Rawlings, Eric Clapton, and many others, but he’s best known as a founding member of the renowned prog-grass group Punch Brothers. Comprised of superlative musicians, they’ve recorded four albums of adventurous acoustic music with such producers as T Bone Burnett, Jacquire King, and Jon Brion.

Throughout his career, Witcher has gravitated toward the other side of the glass, gradually accepting more production responsibilities within Punch Brothers and without. He helmed Sara Watkins’ breakout third album, Young in All the Wrong Ways, in 2016, and this year he produced two new records by his Punch Brethren: Universal Favorite finds banjoist Noam Pikelny going truly solo, just his voice and banjo in a variety of styles and settings, and Witcher ensures it sounds both intimate and expansive. For Mount Royal, the second collaborative album by guitarists Chris “Critter” Eldridge” and Julian Lage, the producer emphasizes their masterful technique as well as their subtle and insightful arrangements. They’re representational albums, he says, but full of verve and skill and even a little mystery.

How did you gravitate toward this particular role?

I had a band with my dad when I was young called the Witcher Brothers, and we made a record when I was 11. That was my first foray into the studio, and I remember having so much fun. Back then, it was all tape. I remember the feel of the machines, getting the microphone set up and coming into the control room for the first time and hearing the sounds of the instruments coming back at me through the speakers. It was a thrill. At that moment, I was hooked on recording. I got a four-track machine, and I spent a lot of time at my cousin’s dad’s house — I guess my mother’s cousin. His name is Don Was, and he’s a huge record producer. He had a bunch of recording gear, and I was always in the studio, setting up equipment and recording for fun. It was something I loved to do in my spare time. When I was about 14, I was asked by someone I didn’t know to play on their record, and that started my career as a session musician in Los Angeles. I got asked to play on other things and, little by little, I managed to build up a reputation. So I’ve always felt at home in the studio.

Were there any particular albums where you started to notice the production?

One of my earliest musical memories was listening to Abbey Road on my parents’ turntable. I couldn’t have been older than two or three, and especially as I got a little older, I remember listening to that record and realizing that there were only four guys in the band, but the sound they were making was much bigger than that. This guy plays the drums, these two guys play guitar, and this guy plays bass. How are they able to get all this other stuff going on? That really opened the door to figuring out what the technology was and what overdubbing was: “How does that work?” I started to think about how they were building tracks and, from then on, a world of possibilities opened up.

When Punch Brothers started making records, I was already an old hand at it and could instinctively take on the role of producer with those guys. Everybody finds his own role within the band, and that became mine. For the last record, Phosphorescent Blues, we had the amazing T Bone Burnett to produce, and I had already been working with him as a co-producer on a bunch of projects — and as an arranger. When you work with T Bone, it means you’re going to hear him say something like, “I’d love for you to write a string arrangement or a horn arrangement for this song.” So you’d do that and, “Okay great, now go record it.” He’s giving you the keys to the kingdom. Sometimes he would show up for sessions and sometimes he wouldn’t, and to have him place that level of trust in me gave me the confidence to think of myself as a producer.

How did that affect the sessions with Punch Brothers?

He was there for all the tracking and he got all the performances out of us, but when it came time for all the editing and mixing, I knew what the band wanted and I knew what I wanted, so he let me take the reins. I was there with the engineer, Mike Piersante, and we finished tracking all the guys. When everybody else had left, I was sitting there with a bunch of hard drives with hours and hours of music — and it’s up to me to edit and oversee the mixing. It was a natural extension of all the things that I’d already been doing.

The band has worked with a different producer on each album. How were those experiences different?

Each producer brings a different aesthetic and a different worldview to the proceedings. Early on, we were very idealistic and dead set on making only representational documents. With The Blind Leading the Blind, we knew it was an ambitious piece, but we wanted to make sure we could actually perform it live. We were very stubborn about capturing it all live, so Nonesuch recommended we get a classical producer. Because that’s what we were doing: We were making a classical piece, so we needed to record it in a classical way with a classical producer [Steven Epstein]. Looking back 10 years later, was that the best way to present that music? I don’t know. If we had to do it over again, we would probably play most of it live and overdub harmony vocals, but you learn.

Jon Brion had a different method on Antifogmatic. He set us up in a semi-circle because he wanted to capture the energy and interaction of what we do. We played all of the music live, but he was able to get a better vocal sound by overdubbing the vocals. I understand that, but it’s very hard when you have five people imagining trying to play based on what they imagine the vocals are going to sound like. We had to learn on the fly how to do that. We had to learn to listen in a different way, and I think it was successful in its own way.

Jacquire King was a lot of fun. He was down for a lot of experimentation on Who’s Feeling Young Now? By that point, we wanted to utilize the studio as another sonic tool instead of just something take a snapshot. We wanted to use the element of fantasy that the studio provides. We dipped our toes in a little bit with that record. We experimented with sounds and overdubs — anything to introduce new things, but always dependent on the song and what it needs. Jacquire really helped us figure out what works for our instruments, and he had us thinking about ways to capture sound that I had never really thought about before.

And the thing with T Bone is, he’s wide open. He wants to do whatever is going to make the best end product. We had different set-ups for different songs. It was a fun process because he’s a master and keeping the bigger picture in mind. The Punch Brothers have a tendency to overdo things and try to squeeze so much perfection out of everything that we squeeze the life out of it. So it was a real education to see how he worked.

What did you take away from those experiences that you’ve applied to your own sessions as a producer?

The most important thing you can have in a producer is trust. You trust that they’re going to understand your vision and you trust that they’re going to help you achieve your goal. It’s such a deep relationship with the rest of the band, and we understand each other so well, that it made sense that I would be the one sitting on the other side of the speakers telling them if they’ve gotten what they want. And I know what they’re capable of doing, so I’m in a unique position to push them. Someone else might be like, “Hey, that was great.” But I would be like, “Hey, that was great but I know you can do better.”

That seems like it would be crucial, especially on these records where there’s nothing to hide behind. It’s just one banjo or two guitars.

Those are very, very representational records without many studio tricks. You approach that kind of project as though you’re making a document. There’s not a lot of fantasy involved. Your job as producer is to put them in a position where they’re comfortable and playing their best, then you have to make sure you capture the sound they’re making as fully as you can. That all sounds very simple, but you become something more like a psychologist at that point. You’re talking a line between keeping people happy and creative, but also trying to find positive ways to shape what they’re doing, to get the best possible results. It helps that the Punch Brothers guys have been working together for so long that we know how to speak to each other in a way that avoids any bad clashes or setting each other off and making them freeze up.

For instance, Noam is extremely thorough — more thorough than I think he needs to be. There’s an interesting dynamic where we’ll work on a song for a couple of hours, and I’ll be very happy with what we got. I’m confident in what we got, so why not come in and take a break before we start working on the next song. But he’ll say, “Let me just do one more. One more time.” Three hours later, he’ll finally feel okay about it even though we have three times as much material as we actually need. He’s familiar with me, but he might not feel as comfortable with someone else to sit there for hours on end. He obviously does feel comfortable: It’s just Gabe. He can’t get mad at me.

As a producer, you have a couple of jobs. One: You’re a proxy for the artist. You’re basically in a position to say, “If I was an audience member, would this be reaching me? Is this going to impact me emotionally?” Two: You have to make sure there is some underlying theme that ties it all together and makes it work as a whole. All the best records tell a story of some kind. It’s all just storytelling. Even though one song is about one thing and the next song is about something else, you can still construct some kind of narrative out of them, even though it may not be a linear story. That’s a big part of the producer’s job: to make sure everything fits together in a satisfying way.

Is telling a story easier or harder with instrumental versus vocal tracks?

They’re challenging in different ways. To create a narrative on an instrumental record, you have to make sure there’s enough variety to feel like you’ve gone somewhere. When you’re making a record, you’re making a 40- or 50-minute piece of music. It might be divided up into 10 or 12 or 15 segments, but you’re making a piece of music that’s roughly the same length as most symphonic music, so you have to approach it that way. You have to piece it together in a way that gives the material shape and keeps it interesting. For a record with singing on it, you have the added difficulty of that extra layer of words. You have to have the musical narrative and then you have to have the lyrical narrative. There’s some wiggle room in there, but you also have to keep in mind the artist and what they’re trying to say. On the Critter and Julian record, they brought in a bunch of vocal songs that were all great, but I just didn’t believe Critter when he sang them. I had to figure out why, which was tricky, but it came down to what I knew about him — where he comes from and what kind of music he has made in the past. The material had to fit within the story of him as a performer, as an artist, and not just within the context of an album.

How does that work with someone like Sara Watkins? What I love about Young in All the Wrong Ways is how it plays against what we know of her as an artist and takes her story in a new direction.

Absolutely. What makes it work with her is that she acknowledges that it’s something different from her. People change and evolve and grow, and this is where she is right at this particular moment. I really felt the honesty of what she was singing to me in those songs. It all made sense. There was a weird incident in the studio with her. All of the songs that ended up on that record were her original songs, but early in the process, she had brought in a song that Benmont Tench had written. It was a new song of his and we had permission to record it. I thought it was good, so we put it on the list. We were about three-quarters of the way through tracking her record when we got to that song. It was just her singing and Benmont playing. The song is dark, about a relationship that’s past its prime and she’s struggling to break from it. She started singing, and the mood in the studio shifted. It had been very happy and positive and constructive, but it turned really dark really quickly. It had been easy-going up to that point, and I watched everybody get very frustrated.

The next day, Jay Bellerose, who plays drums on the record, was talking to me and asked me what happened. The only thing we could come up with was that the song just wasn’t her voice. Nobody believed it, when it was coming out of her mouth. It was a case of the wrong song for the artist, and it’s the only song that didn’t make the record. Don’t get me wrong: It’s a great song, when Benmont sings it. It’s his experience. It wasn’t Sarah’s experience. There was just something about the vibe of the song that wasn’t right for her.

It’s extremely hard to explain that kind of thing, and everybody feels it in a different way. The studio is such a vulnerable space, especially for the person who’s being recorded. It’s such an intimate setting that interpersonal dynamics become the thing that makes or breaks a record. You’re going for an indescribable feeling — something way beyond playing in time or singing in tune, all the technical aspects that make a good performance. When you achieve that next layer, it’s hard to describe. There’s an energy that comes from getting the right people in a room together. Sara’s record was successful because we got the right people playing the right music, which becomes a positive feedback loop. Good things start happening, which inspire more good things, which inspire more good things, and then you have this wonderful document of that time and those people. This kind of thing never happens, especially when you hire a band, but for Sara’s record, people were hanging out in the studio after the tracking was done. We would play for hours and hours, then we would do overdubs in the evening and people would just hang out. We’d open a bottle of wine and people would just hang out in the studio. It was beautiful.

I feel like people sometimes fixate on gear — finding the right pedal or using a certain kind of microphone. That seems much less important to these sessions.

That’s exactly right. People can get caught up in the technological aspect of the studio — at great detriment to the music. At least in regard to the music that I’m interested in making, we have way too much ability to manipulate sound. I hear so much recorded music that has no vibe, no human quality to it. It sounds like the people weren’t even in the same room and maybe not even in the same country when they recorded it. It’s all been pieced together very carefully, but it’s missing an essential element: There’s no interaction. Some people can do beautiful things that way. For what Radiohead does, it’s great. They’re able to use those tools in a musical way. But the music that I want to make has to feel, in some way, like it’s being passed from person to person. It’s interesting because, when you nail it, it’s the kind of thing that sinks into the background. It becomes so effortless that you don’t think about it. It’s the same with movies: You know a director has done his job right when you can’t tell that they’re even there. The goal is to get lost in the storytelling.

Photo credit: Brantley Gutierrez

BGS Class of 2017: Preview

This is going to be an exceptional year in roots music with new releases coming later on from Jason Isbell, Lee Ann Womack, Holly Williams, Chris Stapleton, Chuck Berry, and so many more. Here are some albums we’re excited about dropping in the first half of 2017.

Natalie Hemby: Puxico

Ani DiFranco: Binary

Pieta Brown: Postcards

Rhiannon Giddens: Freedom Highway

Alison Krauss: Windy City

Rodney Crowell: Close Ties

Caroline Spence: Spades & Roses

Valerie June: The Order of Time

Noam Pikelny: Universal Favorite

— Kelly McCartney

* * *

Jaime Wyatt: Felony Blues

Rhiannon Giddens: Freedom Highway

Natalie Hemby: Puxico

Alison Krauss: Windy City

Sunny Sweeney: Trophy

Pieta Brown: Postcards

Nikki Lane: Highway Queen

Caroline Spence: Spades & Roses

Rogue + Jaye: Pent Up

— Brittney McKenna

* * *

Mark Eitzel: Hey Mr. Ferryman

Ryan Adams: Prisoner

Alison Krauss: Windy City

Nikki Lane: Highway Queen

Rhiannon Giddens: Freedom Highway

Old 97’s: Graveyard Whistling

Valerie June: The Order of Time

Hurray for the Riff Raff: The Navigator

Various: From Here: English Folk Field Recordings

Bruce Springsteen: TBA

— Stephen Deusner

* * *

Tift Merritt: Stitch of the World

Leif Vollebekk: Twin Solitude

Ryan Adams: Prisoner

Jesca Hoop: Memories Are Now

Rhiannon Giddens: Freedom Highway

Gold Connections: Gold Connections (EP)

Hurray for the Riff Raff: The Navigator

Laura Marling: Semper Femina

Michael Chapman: 50

— Amanda Wicks

* * *

Ryan Adams: Prisoner

Nikki Lane: Highway Queen

Rhiannon Giddens: Freedom Highway

Hurray for the Riff Raff: The Navigator

Valerie June: The Order of Time

Dead Man Winter: Furnace

Laura Marling: Semper Femina

Son Volt: Notes of Blue

Sera Cahoone: From Where I Started

— Desiré Moses

* * *

John Moreland: TBA

Rogue + Jaye: Pent Up

Rhiannon Giddens: Freedom Highway

Nikki Lane: Highway Queen

Little Bandit: Breakfast Alone

Ryan Adams: Prisoner

— Marissa Moss

RECAP: BGSNorth at the Winnipeg Folk Festival

Last week, the Bluegrass Situation hopped a flight north to Winnipeg, settling in for a weekend of new sights and good tunes with our kind neighbors up in Canada. The festival, which has been going since its inaugural year in 1974, was kind enough to let us take over a stage and be a part of the tradition on Friday for an evening of back-to-back, harmony-filled, banjo-driven goodness capped off by our first-ever #BGSNorth Album Hour Superjam of the Eagles' Hotel California — and the artists rose to the challenge.

Noam Pikelny, the banjo virtuoso of Punch Brothers’ fame, MC’d the event with a heavy dose of dry humor, introducing guests before their performances and returning to the stage for brief interviews during set changes.

By the time the main event revved up, Nicki Bluhm and the Infamous Stringdusters had already railed through a set of their own, so they felt like old friends with the audience as they walked out on stage for the anti-encore — album opener and title track “Hotel California.” Bluhm’s smooth vocals paired well with the deft instrumentals of the bluegrass group for a rendition of the number that had the sizable song singing every word.

The Wild Reeds had already won over many attendees with their earlier set on the stage and were greeted warmly for their take on “New Kid in Town.” Strong harmonies — and stage presence for days — would make this three-frontwomen band compelling enough a cappella, but the rock elements on instrumentals take the Wild Reeds to the next level. Their performance of “New Kid in Town” felt even sweeter with the addition of Pikelny, who had raved about their performance from the stage earlier in the evening and added a certain fullness to the performance.

Canada’s own Foggy Hogtown Boys were faced with high expectations as they came out for hit single “Life in the Fast Lane,” and the group emerged as some of the most skillful and good-natured performers of the evening. Even low-key attendees sitting in chairs couldn’t help but move a bit to the music, and the smiles on the faces of these classic bluegrass players were contagious.

One of the high points of the evening came from Rayland Baxter, who sauntered onto the stage, a lone keyboardist accompanying him, to croon through a swoon-worthy “Wasted Time.” Baxter really made the number his own, hamming it up a bit and delivering the kind of performance that would delight your grandma right alongside your stoner buddy. “Wasted Time” may not have been one of the Eagles’ marquee numbers, but Baxter’s rendition surely gave Eagles newbies a reason to take a listen.

Pikelny took the spotlight next, choosing to perform solo for his interpretation of “Victim of Love.” Quips about the Eagles secret origins in the heart of Appalachia (What? You didn’t know about those?) gave way to a hearty run-through of the track on the banjo. It was easy to ignore Pikelny’s sarcasm and just agree with him: Maybe acoustic, solo, and on the banjo really is how the song was destined to be played.

San Francisco up-and-comers Brothers Comatose brought the Wild Reeds back out for help on backing vocals for album track “Pretty Maids All in a Row,” and their well-rounded harmonies on the vocals gave the song an added intensity. After that, the Infamous Stringdusters returned to the stage (sans Bluhm) for “Try and Love Again,” delivering a performance that was a likely favorite for classic bluegrass fans in attendance.

One of the interesting things about playing a full record from start to finish — in the live setting, at least — is that the set list isn’t a surprise. There is no way to hold the audience hostage by saving the well-known tracks for last, and certainly some would opt to beat the traffic and leave before the end of the set. Fortunately, Massachusetts band Parsonsfield’s stage-closing performance of Hotel California’s final song, “The Last Resort,” felt like a real finale. The five-piece drew out the lyrics in dramatic fashion, a wink to their own New England roots fueling a vibe that didn’t need an up-tempo track to feel like a climax.

The whole experience left us ready to turn around and put the whole show on again. Whaddaya say, Winnipeg Folk Festival?

Photos by Travis Ross and Buio Assis

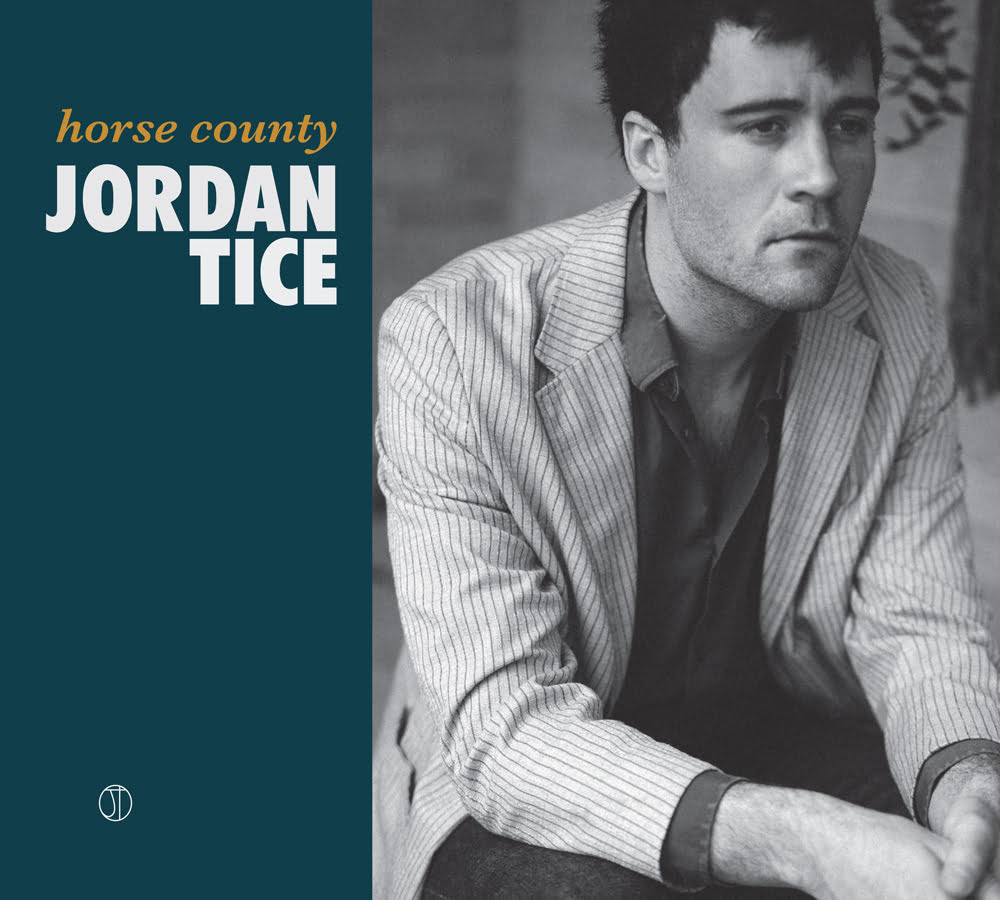

STREAM: Jordan Tice, ‘Horse County’

Artist: Jordan Tice

Hometown: Nashville, TN

Album: Horse County

Release Date: July 12

Label: Patuxent Music

In Their Words: "Here's what happened: I wrote six songs and five instrumentals, and got some really good pickers to play them with me. I'm talkin' Paul Kowert-Mike Witcher-Dominick Leslie-Brittany Haas-Shad Cobb-Noam Pikelny good. Chris 'Critter' Eldridge and I co-produced it and saw the thing through. There's a little something for everyone on here — old, new, sad, goofy, a rag — and it's all rolled in that Horse County dirt." — Jordan Tice

Photo by Emilia Paré. Design by Loren Witcher.

Recap: The BGS Late Night Windup at AmericanaFest 2015

The Americana Music Festival & Conference is, as its name would imply, a festival, but it's also something of a family reunion. For music industry folks, journalists, and especially, artists, the annual Nashville festival can serve as one of the only times of year the gang is all together, and as such is one of the year's biggest parties.

Spirits were high at The Basement, a music venue beneath famed record shop Grimey's, for The BGS's Late Night Windup, one of the festival's first official events, where attendees could pick up their badges before going inside to enjoy a stacked night of music.

[The BGS's Amy Reitnouer with the house band]

Della Mae and the Wood Brothers kicked off the event with their own solo sets, before taking their spots in the crowd to await the jam. Both played to a packed room, treating the audience to tunes new and old.

Our own Amy Reitnouer introduced Punch Brothers' banjo extraordinaire Noam "Pickles" Pikelny as the evening's master of ceremonies. Pikelny was joined by a house band consisting of fiddle player Christian Sedelmyer, Casey Campbell, Mike Bub and fellow Punch Brother (and newly bearded) Chris "Critter" Eldridge. Together, they provided a backdrop for a long list of special guest and surprise artists over the course of the next couple hours.

The first guest was Sedelmyer's own project 10 String Symphony, a duo with fellow Nashville musician Rachel Baiman. It ended up being a mostly covers affair, with Eddie Berman following with a cover of Paul Simon's "You Can Call Me Al," trailed by Caitlin Canty paying homage to Dolly with her own take on "Wildflowers."

One of the highlights of the night was what Pikelny dubbed "Mandolin Armageddon," in which all of the musicians on stage packed up their instruments, hopped on a space ship and saved us all from an asteroid. Just kidding — it was cooler. Sierra Hull, Casey Campbell and Della Mae's Jenni Lyn Gardner joined forces for an incendiary performance of Bill Monroe's "Big Mon," and we think that, had an asteroid been headed our way, it would have stopped in its tracks so those talented kids could finish their tune.

After Mando-geddon came shuitar time, when The Wood Brothers returned to the stage to cover Bob Marley's "Stop That Train." Kelsey Waldon then schooled the audience on lesser-known country singers when she performed a Vern Gosdin tune. Rayland Baxter, a self-described "super stoner" who only rememebers the lyrics to his own songs, required a little audience help for his take on Graham Nash's "I Used to Be King," and the audience happily obliged.

As the night wore on, guest after guest, including Leigh Nash, Shakey Graves, and Della Mae, joined the house band for jam after jam, each one rowdier than the last. We couldn't think of a better way to kick off one of our favorite events of the year. If you joined us for last week's jam, we hope you enjoyed it as much as we did. Sorry about that hangover.

Photos courtesy of Kim Jameson