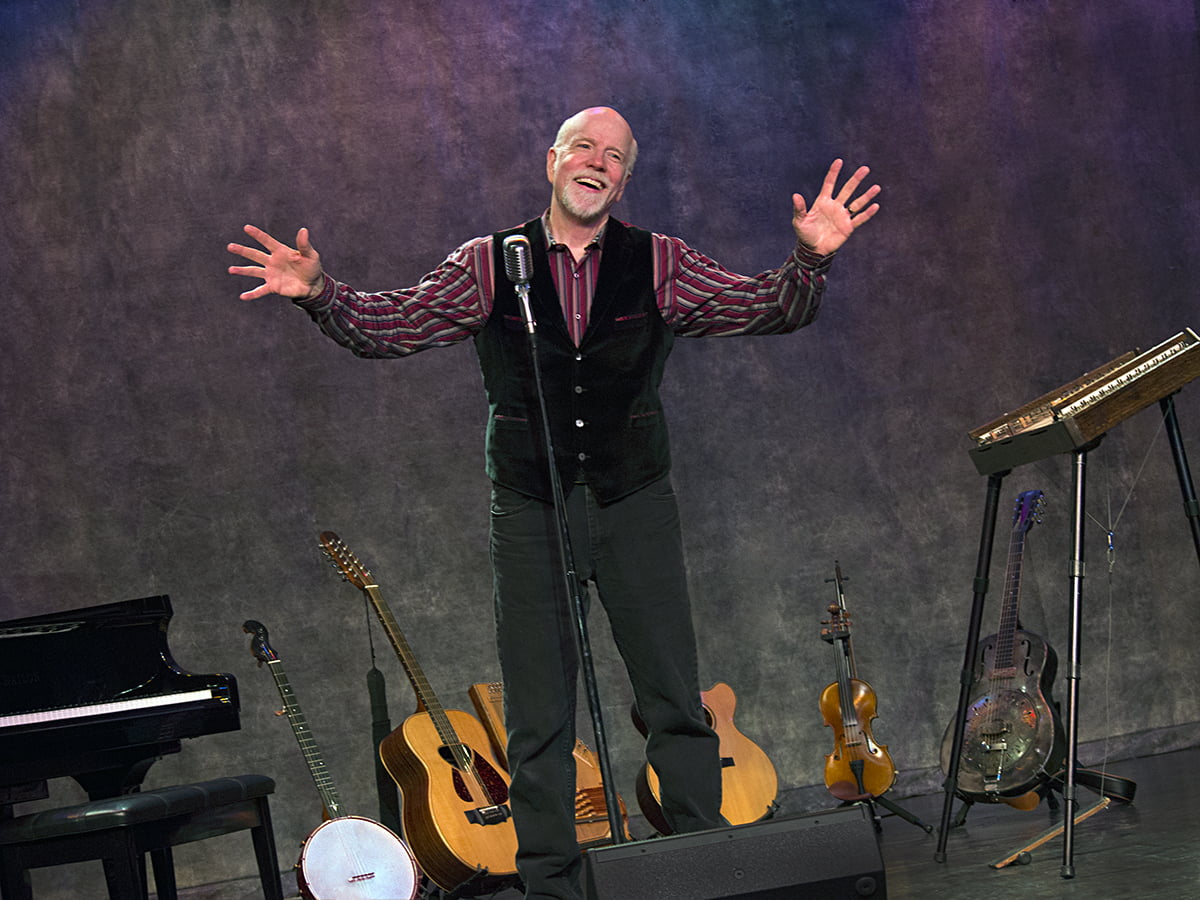

Pete Seeger was a prolific songwriter, a dogged activist, and a folklorist who believed in magnifying voices from every corner of America. He used his music to further causes from Civil Rights to environmental preservation, and he never let the magnitude of a task scare him away from a fight for what he believed in. The spirit of servitude that Seeger brought to the world didn’t die when he passed away in 2014, and that fact is perhaps most evident at Newport Folk Festival, the now-iconic event that Seeger helped George Wein get off the ground in 1959. “The spirit of Pete, and of Pete’s egalitarian nature, is in every ounce of this festival’s DNA,” says Jay Sweet, executive producer of Newport Festivals.

To coincide with what would have been Seeger’s 100th birthday this month, Smithsonian Folkways released a six-disc anthology celebrating Seeger’s astounding career, complete with twenty unreleased recordings and a hardcover book detailing the many ways Seeger was a catalyst for positive change, both in American culture and the world at large. Pete Seeger: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection is a window into the life of a musician who shaped American folk music, but it’s also a road map for those who hope to advocate for positive change themselves.

“We can’t complain about what’s happening to us in the present day unless we start giving the kids the strength and the wisdom and the history of what came before them, and ask them to really pay attention,” Sweet says. Here, the festival producer discusses what Seeger taught him and how he’s using Newport to spread Pete’s message to a new generation.

Editor’s Note: Read the first part of our BGS interview with Jay Sweet.

BGS: You can tell a lot about a person by how they handle a disagreement. Did you ever argue with Pete?

The biggest disagreement I had with Pete was never about any kind of problem he had with rock or electric guitar or any of that. It was that he didn’t think we were doing enough. For a while, the nonprofit’s mission statement was, first and foremost, to keep the Newport Folk and Newport Jazz Festivals going in perpetuity, and then to help continue introducing these genres of music to students and young people. Well, Pete thought that was back asswards, and he let me know it.

The thing is, we’re not publicly traded — there’s no AEG, there’s no massive underwriting sponsor. Newport is hand to mouth, like most nonprofits. But he thought it was wrong to take the financial benefit from the festival and put it back into an endowment to ensure that we could keep this festival going. Pete wondered why we did that—to which I replied that I happen to think it’s important to keep this festival going! [Laughs] But his point was that every year we should be giving every dollar we can back. He didn’t care whether it was music education, environmental issues, housing for the homeless. It was, “Why save for the future if you can affect the present?”

That mantra seems like it’s become more and more a part of what you do.

Because of Pete, we realized maybe we did have it back asswards, in some respects, and that the best way to do this would be to flip our mission statement—now, it’s primarily to provide music education for those in need, and to use these festivals to draw attention to the need. We’ve gone from being a company that works year-round to put on two festivals to being a nonprofit that works year-round on music education, and celebrates that yearlong work with two big supporting parties.

For years, Pete was shaking his head and saying we could do more. [His disapproval] was really tough to hear—if we don’t have enough money, [I worried] we might not be able to do [the festival] at all. We had it backwards because we were trying to look out for the future, but the future is now. Pete’s reason for starting [Newport] was to effect change by giving a platform for the freedom of speech, freedom from rules. And if you’re always giving money away, you’ll find a way to do it. You will find a way to throw the festival if you’re helping people.

One of the ways Pete used Newport to effect change was during the Civil Rights era—he will always be known as a fierce advocate for equality. How can you honor that with what you do at Newport?

Equal rights was one of Pete’s biggest causes. Newport was one of the meeting points for the Civil Rights movement—[the festival] was always being watched by the government, and people learned how to sing the marching songs in workshops with Pete at Newport. All these Cambridge, Mass., and Ivy League people would come, and he’d say, Let’s get on these buses now, and go South and stand with our brothers and sisters. It was very politicized and very political at the time.

But the spirit that I take away, that I continuously turn to almost daily, is the egalitarian nature of Pete. At Newport Folk in particular, that egalitarian nature lives on. We’re all in general admission, and there’s no VIP pass to purchase. We don’t do a poster where [artists’] names are in different font sizes, or anything like that. If you’re playing, you get the same treatment whether you’re a five-hundred dollar artist or a five-thousand dollar artist or — well, I won’t say fifty-thousand because we won’t really ever pay artists that much. [Laughs] There are plenty of five-hundred-thousand-dollar artists who play Newport, but we basically tell them, ‘You need to check your ego at the Pell Bridge, because it will not fly at Newport.’ Because of that, we’ve been able to foster a community, that does go back to “We are all equal,” but it also promotes all opportunity for all people beyond the festival.

Pete stood for using music to effect change. As a person who always had an instrument on him — walked around with a banjo and a guitar for his entire life, or a penny whistle — Pete took for granted, I think, that music would always be in the curriculum for all kids. I never once think he considered there might be a world where there are five million kids in the United States who don’t have access to music education. And that’s just access to any music education—I’m not talking about the uncounted amount of broken instruments, or the fact that sports teams get brand new uniforms and stadiums and lights, when the music departments get nothing. Those things would shock Pete because he used music as his medium. We think the best way to create more Pete Seegers is to actually give more people access to music.

One could argue that, with Newport, you are fostering the next generation of legends. What do you look for in up-and-coming artists, and how do you help bring those attributes to the forefront?

I think it goes to what we were just talking about. It’s the people who I can’t see doing anything else. There is no separation between showperson and who they are off stage. To me, a folk artist is not necessarily someone who puts on a persona and comes out and creates. And by the way, there’s nothing wrong with that. I’ll say some of the best pop performers in the world come off the stage and they resemble nothing of the personality they bring to a show. But I think a true folk artist is somebody who can’t separate it. What you see is what you get. …

Newport, to me, is not just a platform for artists to be able to speak their mind in a safe environment. Yes, that was its blueprint from the minute it was conceptualized but that was when other platforms didn’t exist. [“Needing a platform”] meant that you couldn’t break into radio and you couldn’t break into TV. Now there’s a festival on every g-ddamn street corner, and with the Internet, everybody can get their fifteen minutes of fame.

But Newport continues to represent a true sense of community. You are not alone out there, in a van doing three thousand miles every month. You have a place. No matter how far you go, you can feel tied, feel a weight off your shoulders, and have a rest from the corporatization of music and the sludge factory that’s out there for a lot of these people to make a living. If I can offer that respite and a sense of community and a sense of home, that, to me, is just as much a part of Pete’s legacy as anything else. This idea that we’re in this together. If you’re part of our tribe, we’re fiercely loyal. And the door is pretty open if you leave your ego behind.

Illustration: Zachary Johnson