Linda Gail Lewis was never destined to be the most renowned member of her family — or second, third or fourth-most famous, for that matter. There’s not a lot of oxygen left in the shotgun shacks of Ferriday, Louisiana or the public mindset when you have original rock wild man Jerry Lee Lewis for a brother and your cousins are Mickey Gilley and Jimmy Swaggart. But unlike her early-starter kin, Linda Gail has come more into her own later in life. The 71-year-old little sis has emerged as a heroine to the rockabilly crowd not just because she trades off the trademark style of the Killer but because she has slayer instincts, too.

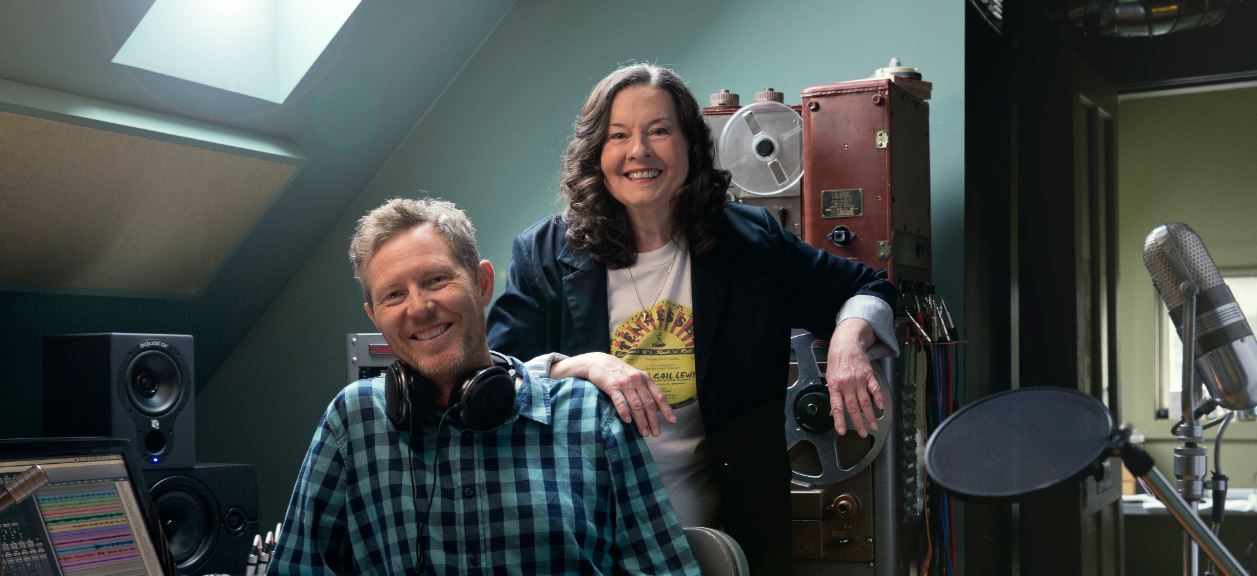

Still, she’s traditionally benefitted more from being a duet partner than a solo act. She recorded and toured with Jerry Lee in the ‘60s and ‘70s — the sibling duo had a Top 10 country hit in 1969 with “Don’t Let Me Cross Over” — and then she reentered the consciousness of the music intelligentsia in 2000 when no less a fan than Van Morrison asked her to make a joint album and tour together. Now, she’s on to her third partner in musical crime: the alt-country great Robbie Fulks, who joined her for Wild! Wild! Wild!, an album he produced all of, wrote most of, and participated on as an equal vocal partner only with some urging.

So how does Fulks stack up against his two famous predecessors in the duet partner’s seat?

“I was the best of them all, I would say,” Fulks says. “Oh, sorry, go ahead.”

“Absolutely!” Lewis agrees, although when it comes down to it, she may not quite be ready to declare new Bloodshot Records partnerships thicker than blood. “Singing with my brother and Robbie, I love one as much as I do the other, which is saying quite a lot. And I don’t mean to say anything bad about Van. I appreciated doing the album [You Win Again] with him, and it was good for my career, and… I wouldn’t say it was actually fufn in the studio, but I did get through it, and I lived to tell the tale,’” she says, laughing. “It was impossible to really match up with him on the recording, because his phrasing is so different from my brother’s. But Robbie’s is similar enough that it was easy for me. You’re every bit as great as those other two, Robbie. And don’t tell my brother I said that.”

“I’m not telling anybody you said that,” Fulks says. “Maybe my wife.”

Wild! Wild! Wild! includes five true duets, two Fulks solo vocals, and six that feature Lewis alone as frontwoman. If that math leads you to suspect that the project might’ve started life as a Linda Gail Lewis solo album Fulks was producing before it became co-billed, your guess would be right.

Says Fulks, “The idea was a little bit imposed on us because the label said, ‘Well, we’d rather have a duet record,’ and that wasn’t what I originally had in mind. Duet singing with her, nobody would say no to that. And I think male-female duet singing is just about my favorite kind of country music. So to be able to write to that and then to perform with her was just a whole other level of fun over, you know, sitting in a chair and listening to people play.” Lewis, too, was happy it became a duo project, and cites “I Just Lived a Country Song” as her favorite track on the album, even though that’s one of the two tracks that Fulks sings without her.

To the extent that it’s partly a Robbie Fulks record, it’s an old-school Robbie Fulks album, which should tickle a lot of long-time fans who’ve charted his changes. It harks back to early- to mid-period records like 1996’s Country Love Songs, 2005’s Georgia Hard and 2007’s Revenge! when Fulks was the master of classic country pastiche, writing severely clever tunes with tellingly witty titles like “Goodbye, Cruel Girl,” “All You Can Cheat” and “The Buck Stops Here” (as in Buck Owens, of course).

There is certainly some pure country on the album to go with the more snare-smashing stuff, like their duet on “That’s Why They Call It Temptation,” which he wrote rather overtly in the George-and-Tammy mode. (Sample lyrics — Robbie: “I tried to keep my hands from where they longed to go.” Linda: “And I did all I could to help you, short of sayin’ no.”)

Meanwhile, there’s a Tennessee-meets-New Orleans horn section on a Fulks-penned tribute to Lewis’ adopted hometown, “Memphis Never Falls From Style,” which has Linda singing the lines, “Thank you Memphis for the great insight/That music is a drag if it’s too f—in’ white.” They went back and forth over whether to keep her singing the F-word; “I grew up on the road with a bunch of musicians, and I have no problem with a little profanity,” she says. But ultimately Fulks decided that a loud bleep was called for, out of nostalgia, if not bashfulness. “I remember being 8 years old and hearing ‘Johnny Cash at San Quentin,’ and those bleeps would come on real loud, and it reminded me of being a kid and the joy of bleeped-out profanity, which you don’t get to hear anymore.” For Lewis’ part, “I was worried about being in trouble with my brother. So I was happy to have the bleep,” she laughs. “And I plan to tell him that I didn’t really say it.”

Jerry Lee Lewis was into his country period — having fallen out of favor as the British Invasion superseded America’s pioneer rockers — when he started enlisting his little sister to join him on records and at shows. (For example, a 1973 performance of “Roll Over Beethoven” on the Midnight Special program.) Their sole hit together was a cover of the Carl and Pearl Butler song “Don’t Let Me Cross Over.”

“Jerry was a big fan of theirs and they were good friends of ours, and we never felt right about covering their song,” Linda admits. “But still we did it, and it was Kenny Lovelace’s idea,” she adds, mentioning her brother’s long-time sideman — and one of her ex-husbands. “Jerry and I had trouble getting through it because we were singing a love song and we’re brother and sister. We were on the same microphone, and we would look at each other and start cracking up. We only were able to get through it once.”

“That’s a little like Nancy and Frank Sinatra singing ‘Something Stupid’ together,” says Fulks, “although that was a lot creepier, I think.”

The sibling duo act came to an end out of jealousy, she says. “My sister-in-law at that time hated me and didn’t want me to be around, so I had to go,” Linda says. “And you know, sometimes even your enemies will help you. Because had she not done that, I would never have left my brother, and I would never have had my own career, and I never would have learned to play he piano. All the things my brother had shown me through the years helped me when I started playing rock and roll and boogie-woogie piano in 1987. My brother’s fans were coming to see me, and they wanted to hear ‘Great Balls of Fire,’ so I had to make sure that I could play it, especially because the piano player that I had in my band in Memphis had no feel for it.

“And I’ve had such a wonderful career, and now of course, with, this great album that I have with Robbie, I feel so blessed. To me it’s the highlight of my career, and life. I don’t think I’ve ever been this happy. And I just looooove my ex-sister-in-law that hates me, because she did this wonderful thing for me.”

Before they made the album, Fulks once blogged that hearing Linda Gail play piano put him in mind “of a cotton field with a candelabra in it.” He sounds embarrassed to be reminded of the phrase now. “Oh my God,” he says. “I didn’t realize I said that. It’s alliteration, anyway. It sounds like literature. ‘Cotton fields…’ I better stop blogging.” Lewis offers him a sharp retort. “Don’t you dare! I loved that. I actually saved that in my iPhone so I can just go back and read it over and over.”

In a separate conversation, Fulks talks about how his appreciation for Lewis developed. “You just say Jerry Lee Lewis’s sister and then go on to say yes, she plays like him and she’s a great singer, and she’s been doing it for 50 years or whatever, and that gets people interested. … With Linda, her voice and her career are so tied into his, it would be hard to separate it out too much, and a good deal of her act is a tribute to and an expression of love for him. But to me she’s interesting partly for the fact that she’s a woman in that family, and just as I’m interested in what it was like for people like Jean Shepard to get along on the road with Ferlin Husky and those guys in the ‘50s, I’m interested in what it was like for her to be part of that clan in the ‘50s and ‘60s, and to be holding her head above water.”

And he’s fascinated by the nature-versus-nurture aspects of the playing she picked up later in life. “She’s a great piano player, and it doesn’t really doesn’t boil down to the notes that she’s playing,” Fulks says. “It’s kind of a family style and a genetic style, and there’s something that’s unlearnable about that style. Anybody could read this off of a sheet and make the moves, but nobody could sound like that. I looked at her the other night when we played together, lifting her hands a foot and a half above the keyboard and banging down on two notes repeatedly, and you just think, well, that’s ridiculous! It’s a real mystery, and it’s thrilling to hear.”

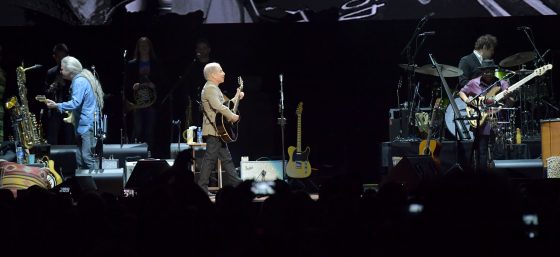

Photo credit: Andy Goodwin