When life hands you lemons, sometimes it’s better to just burn them and start anew rather than make lemonade. That’s exactly what India Ramey does on Baptized By The Blaze, the singer’s empowering fifth album that sees her shedding the trauma that had haunted her since seeing her father abuse her mother as a child.

For years Ramey tried coping by working as a domestic violence prosecutor, but turned to music when that career fell apart in 2009 with her first album, Junkyard Angel, already in hand. Despite all the pain her father inflicted, she says her first musical memories were with him.

“He’d play Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson’s Wanted! The Outlaws on repeat,” Ramey tells BGS. “Through that I became obsessed with Jessi Colter. I’d get my mom’s curling iron and sing her songs while standing on our living room ottoman. I always say that my dad was such a bad guy. He never gave me anything except for my love of country music.”

But as Ramey’s own career in music materialized, a 12-year dependence on the daily tranquilizer Klonopin began to rear its head. Taken to quell the panic disorder that’s lingered since first witnessing her abusive father’s actions, Ramey sought to gradually come off the drug during the pandemic before its severe withdrawal symptoms landed her in rehab. There, through stubbornness and self-determination, she was able to reclaim the power over her dependence and the trauma that caused it, vowing to never go back. Baptized By The Blaze is her journey to become a better version of herself.

“I went through a lot of stuff — a metamorphosis if you will,” says Ramey. “It was really hard and really scary, but I got so much personal empowerment out of it. Since then, I’ve been motivated to pass that on to bring folks strength and remind them that the tragedies they’ve faced give you superpowers to handle anything else life throws at you.”

Helping Ramey realize those superpowers was her therapist, a conversation with whom inspired the song “The Mountain.” According to Ramey, it occurred about a year into their sessions after something had left her in a puddle of shame and defeat. She explained how our anxiety attacks are similar to avalanches in that we don’t know the tools needed to combat them until going through it. But every time there is an avalanche you’ll have more tools and awareness to recover because you are the source, you are the mountain.

“It was the most empowering thing anyone had ever said to me in a moment where I was so vulnerable,” admits Ramey. “It left me feeling so powerful and wanted. This song is my way of spreading that beautiful message she gave to me.”

Another metaphor central to the album comes on its title track, on which Ramey compares her journey of redemption to a phoenix rising from the ashes. It was written while she “was thinking about that moment where I decided to burn it all down, to burn all of those defense mechanisms that I’d put in place to avoid confronting my trauma.” Despite its personal and well-meaning message, the song didn’t always resonate with everyone on her team though, with one person even calling the song over-dramatized. This led Ramey to shelve it for a couple years until producer Luke Wooten chose to include it on the new record.

“As artists, we’re always second guessing ourselves, so to have somebody on my own team tell me I should leave the idea behind really hurt,” Ramey confides. “Because of that, I struggled with self doubt for a long time about going all in on it, but in the end I went with my gut and I’m glad I did.”

Another example of being misunderstood and defying the expectations of others comes on “Piece Of My Mind,” a soft but stern ballad about an industry type who found out about her past working in law and said if he’d known he would just assume all her albums were vanity projects. On it, Ramey’s signature sass shines through as she urges the person to tell them their story: “Just a snapshot is all you see, you don’t know shit about me.” Before going on to describe how “I’ve fought wars and still they haunt me” and likening each day to being Halloween.

“It pissed me off, because that judgment he had was denying me my authentic story,” exclaims Ramey. “He was denying me the suffering that my family and I had gone through because of a job, so this song is me telling people exactly who I am, which is a lot more than any article or bio can capture.”

While most of the album is derived directly from Ramey’s own personal experiences, two songs that veer from that path are “Silverado” and “Down For The Count.” Both are stories about badass women living life on their own terms unburdened by the judgment and shame often delivered through patriarchal transgressions. “Silverado” details a one night stand at the motel El Dorado and “Down For The Count” highlights a streak of promiscuity to get over a past lover (“I put ten men between you and me”).

“The women I wrote about in these songs are people I think any woman will resonate with, because they’re about women doing whatever the hell they want,” she asserts. “It’s about doing things that dudes do all the time without the same level of judgment and are unapologetic about it. They’re my way of giving the middle finger to the patriarchy.”

No matter the delivery, Baptized By The Blaze charts out a journey of empowerment and recovery that is sure to provide strength and an upbeat honky-tonk soundtrack to anyone with a listening ear. It’s also proof that Ramey’s best work isn’t behind her and that her renewed focus has her poised for a bright future, despite the scars that once plagued her past.

“The process of making this record has taught me just how strong and powerful that I am, which are both things I was never convinced of beforehand,” Ramey reflects. “My hope is that it does the same for listeners and helps guide them on their own journeys.”

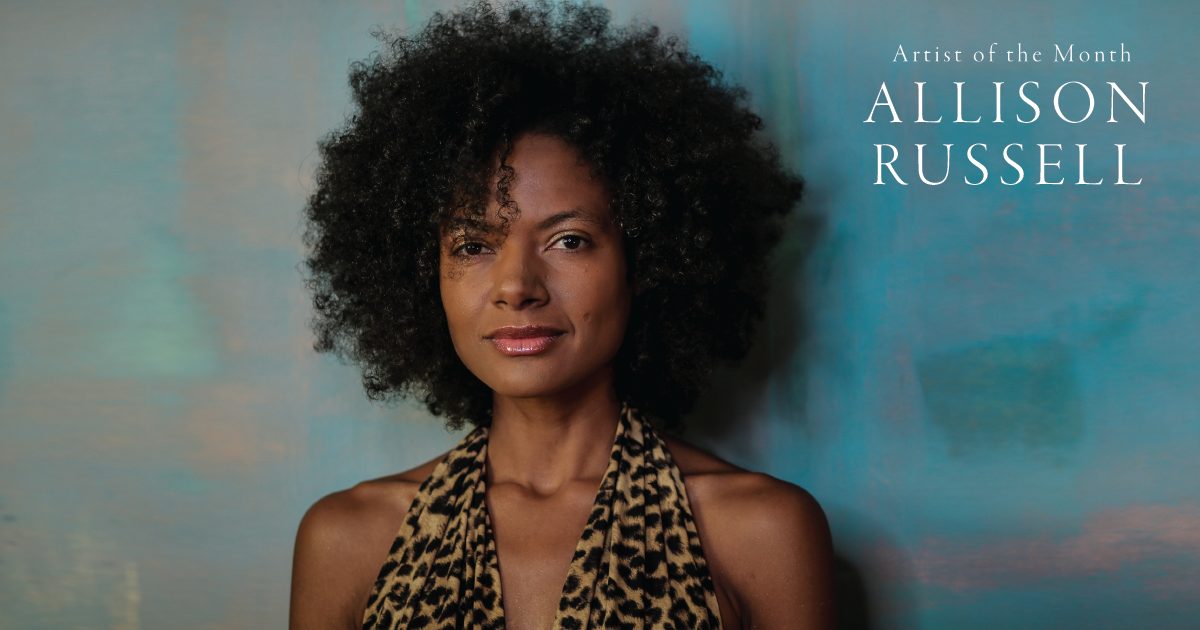

Photo Credit: Stacie Huckeba