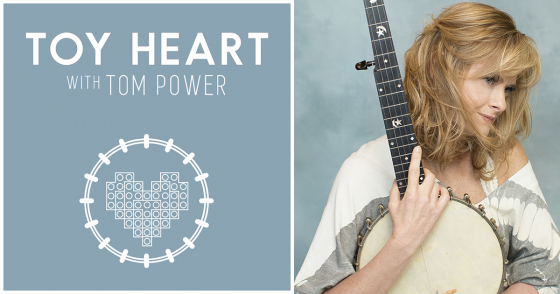

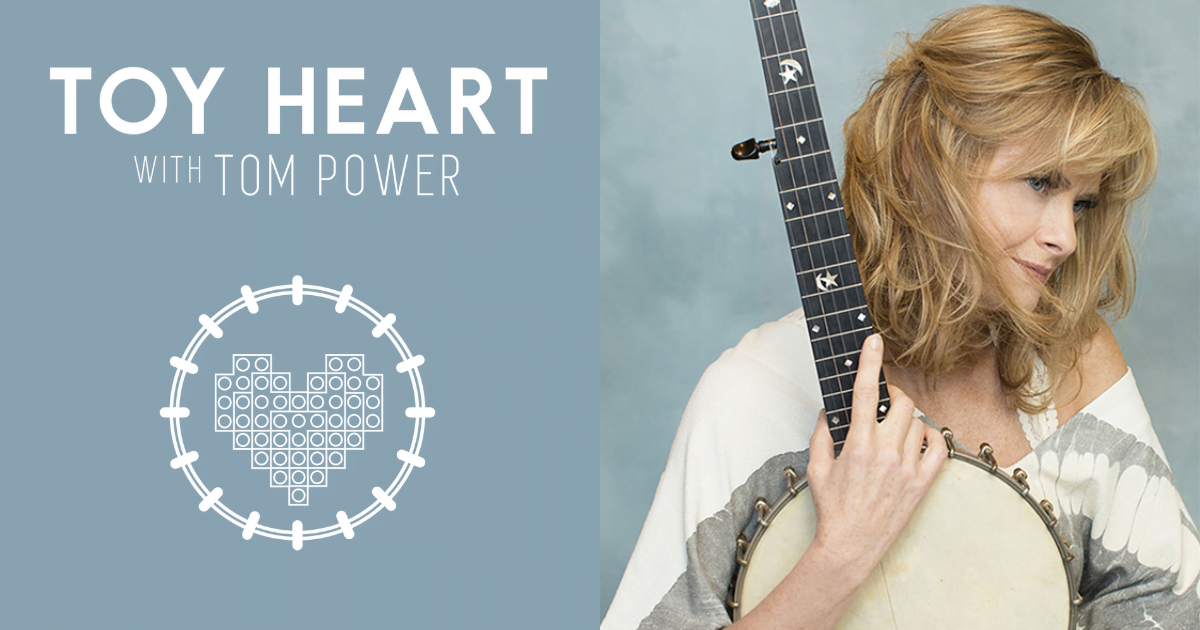

Artist: Alison Brown

Hometown: La Jolla, California

Latest album: The Song of the Banjo

Personal nicknames (or rejected band names): Mom (currently trending)

From the Artist: “‘Here Comes the Sun’ is a song I’ve loved for years. But I never thought about playing it on the banjo until I was inspired by stories of hospitals playing it over their PA systems to encourage staff and patients in their battle against COVID. As I started working on it I realized that the tune has a lot in common rhythmically and harmonically with ‘Águas de Março’ (‘Waters of March’), a Tom Jobim classic that’s one of my favorite melodies and recordings. So I put the two together and came up with this mash-up — setting the low banjo against a tapestry of piano and jazz flute.” — Alison Brown

What was the first moment that you knew you wanted to be a musician?

I didn’t become a musician in one lightning rod moment. It was really more a series of baby steps. When I was really getting into the banjo in the late ’70s there weren’t a lot of successful role models that pointed the way to how you could make a career as an instrumentalist. As much as I loved playing the banjo I really thought it would be a hobby that I would talk about at cocktail parties in my real life as a doctor, lawyer, or another respectable white collar professional. As it happened, I had to spend several years as an investment banker before I got up the nerve to try being a banjo player.

What’s your favorite memory from being on stage?

I have so many great memories it’s hard to pick just one. Collaborating with a skratji band on stage at the Opera House in Paramaribo, Suriname, during a State Department tour is one that has stayed with me. Guesting on Brandi Carlile’s collaboration set with the First Ladies of Bluegrass at the Newport Folk Festival last summer with Dolly Parton singing “9 to 5” is definitely another. Playing on the Banjo Stage at Hardly Strictly Bluegrass in front of a crowd that reaches all the way down Speedway Meadows never fails to blow me away and is one that always validates my decision to leave my investment banking job in San Francisco’s financial district to play the banjo.

If you had to write a mission statement for your career, what would it be?

Since launching Compass Records 25 years ago, my career has had two parallel tracks: one as an artist and the other as the co-founder of a roots-based indie label. When Garry West and I started the label in 1995, literally at the kitchen table, we felt there was a keen need in the market for a record company that was run by musicians. We were driven by the idea that our perspective gained from years of touring would position Compass uniquely in the market. Our goal was to create an artist friendly home for other artists; at the time I was halfway into a multi-album contract with Vanguard Records. Garry and I were, and are still, extremely passionate about discovering new artists and helping to bring their music to a wider audience.

Over the past two and a half decades, we’ve had a chance to help further the careers of an amazing roster of artists across the roots music spectrum and also have had the privilege of carrying the torch forward for some great label imprints through catalog acquisitions. One thing that I didn’t really anticipate when we started Compass was how running a label would inform my own creativity as an artist and producer. Knowing the challenges in the market has been very much of a double-edged sword: sometimes it makes it difficult to get motivated to create new music but, at the end of the day, having a handle on current challenges and opportunities on the business side has made it more natural for me to create music with specific target results in mind.

What rituals do you have, either in the studio or before a show?

For me, studio = food:) When I’m producing, or leading a session, I like to arrive with warm scones or banana bread to start the morning and then make sure there’s a kitchen full of interesting snacks on hand throughout the day. I know it’s not great for the waistline, but for me it adds to the fun of the creative process. I’m also a fan of having slow TV, sound off, running on the monitor in the control room. When I was producing Special Consensus’ record Chicago Barn Dance, we had a Norwegian winter train journey from Oslo to Bergen on a loop while we worked and it complemented our musical journey in a perfect way.

Since food and music go so well together, what is your dream pairing of a meal and a musician?

Hmmm, perhaps not your typical banjo player’s dream, but how about a simple dinner with Tom Jobim on a garden terrace in La Jolla, California, overlooking the Cove and a menu that includes Jacques Pepin’s roast chicken, haricots verts, and a bottle of Cakebread Chardonnay?

Photo credit: Stacie Huckeba.

“Here Comes the Sun” credits: Low Banjo: Alison Brown; Piano: Chris Walters; Flute: John Ragusa; Bass: Garry West; Drums and Percussion: Jordan Perlson