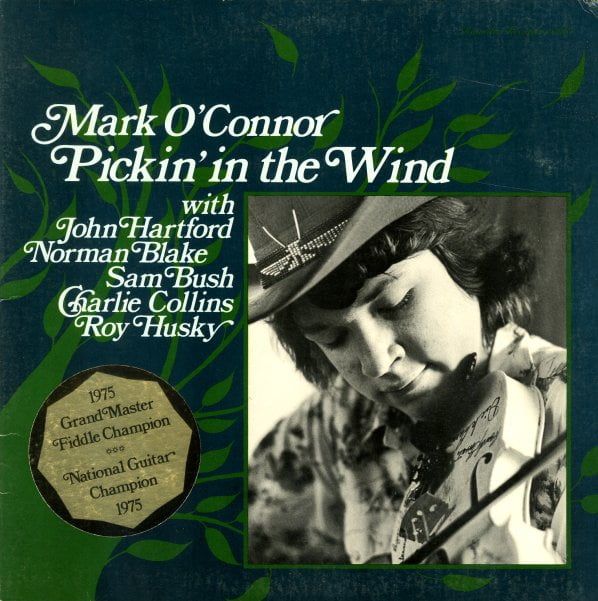

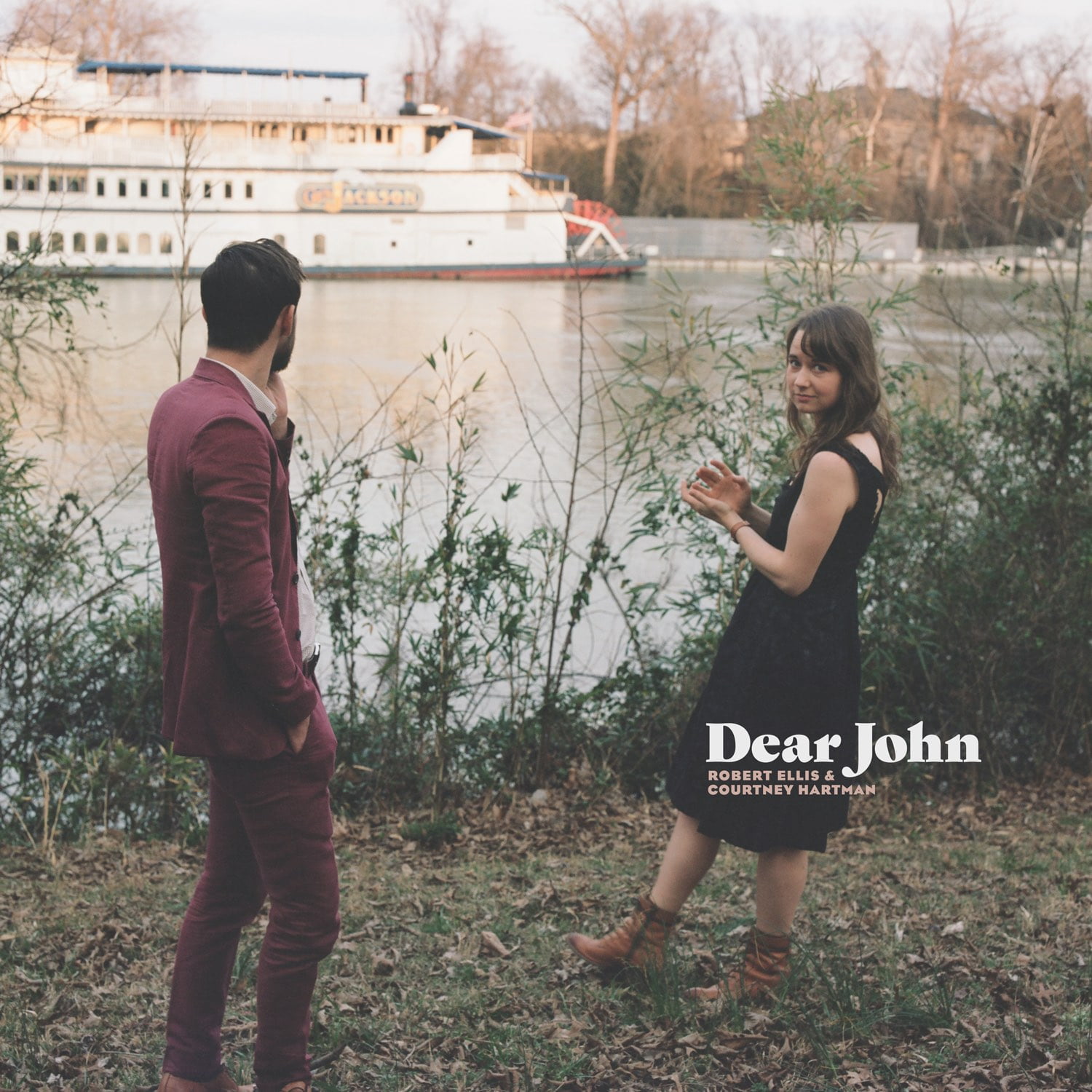

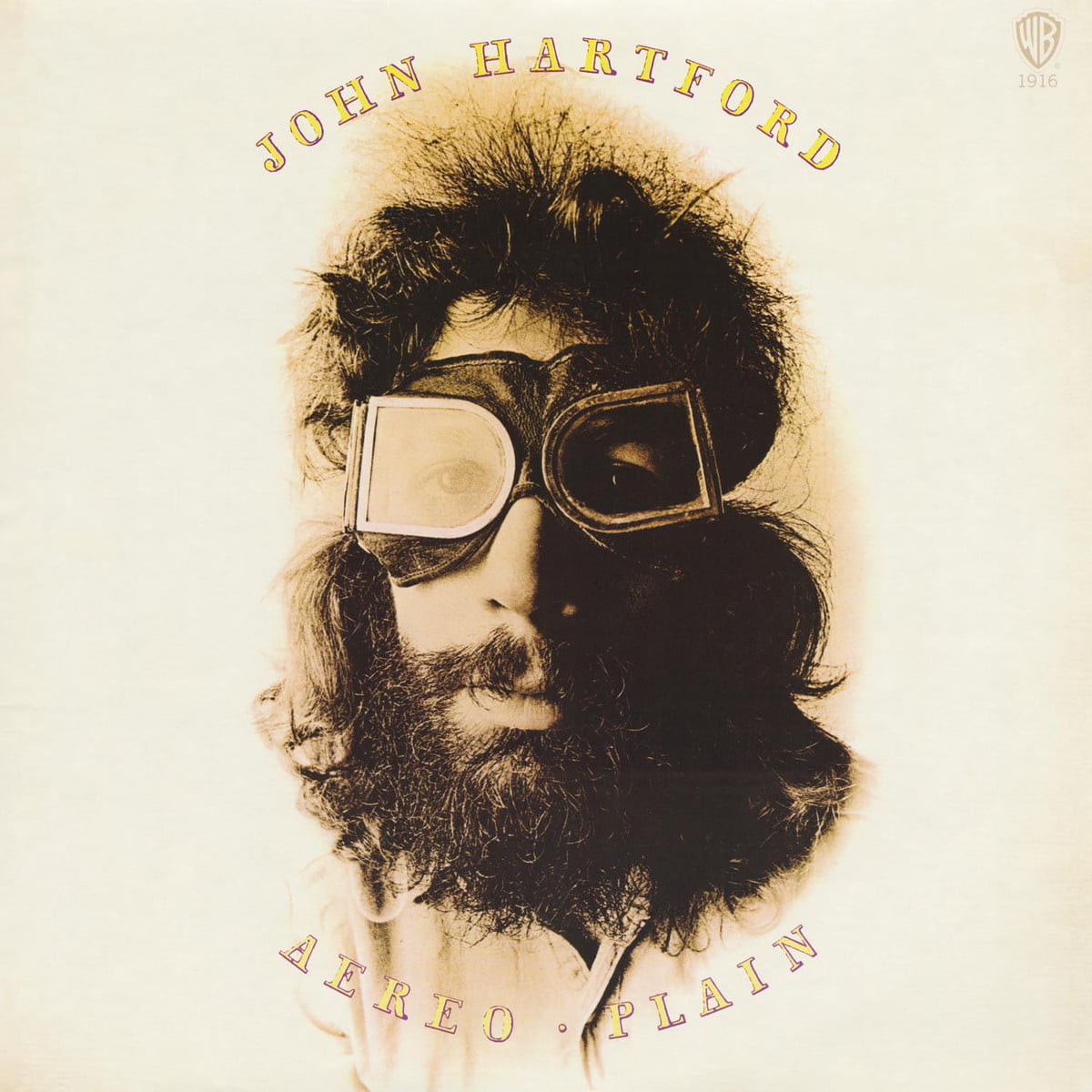

There’s a strangely specific conversation that takes place between two guitars. Long-time friends Robert Ellis and Courtney Hartman know the very kind. They’ve been playing music together for some time now, but they partnered in a new way when they set about to record a selection of folk singer John Hartford’s songs for their collaborative tribute album, Dear John. The musicians — solo artists in their own respect (with Hartman also playing in Americana group Della Mae) — paired their guitars, as well as their voices for a harmonically infused update on Hartford’s work, both known and obscure.

While their voices ebb and flow like the river that runs central to Hartford’s songwriting, it’s their stunning guitar work that elevates the 10-track LP into a conversation within a conversation. The slow, building guitars of “Delta Queen Waltz” trickle like a stream, widening at the first verse’s start to allow Ellis’s and Hartman’s voices space to enter. Then, of course, there’s their take on one of Hartford’s most famous songs, “Gentle on My Mind.” As the song winds down, their guitars spend nearly two minutes in a tête-à-tête that is as evocative as their harmonies at the beginning. Dear John is a winsome nod to the “weird” writing of Hartford told not through his traditional banjo and fiddle, but two very talkative, beguiling guitars.

What was it about this opportunity to sing together that felt so enticing?

Robert Ellis: We’ve been friends for a long time. We’ve been taking every opportunity to play together ever since we met. I think the tour and the record are products of that vibe of enjoying each other’s company.

Courtney Hartman: Exactly. And, actually, the record had been made before we toured.

What about Hartford’s songwriting feels modern or timeless to you, and how do you feel his subject matter still resonating?

CH: John Hartford writes really specifically and really poignantly, and I think those lyrics will always feel timeless. He would also write some really specific cultural or political or environmental songs, and I think they’re still very relevant today.

RE: Yeah, I think that’s a strength of his style. I was explaining to a student the other day — we were talking about writing — I think, when we’re young, all of our instinct as writers is to want to be profound, to search for this way to say something meaningful that no one has said, or just say something in this unique or profound way. I think, as we get older, we figure out that the most profundity there is in the universe is in the little details of, you know, ironing your shirt or the weird interaction you had with a lover at a coffee shop. There’s something about the very specific narrative nature of that tradition that makes these profound things happen. I think, for John Hartford’s stuff, they’re specific ideas about a specific thing happening, and that says something about this much larger, more important thing.

Speaking about his political songs, “Old Time River Man” comes to mind because I couldn’t help drawing parallels to, let’s say, “Peg and Awl,” and the plight of the laborer. Even that feels relevant still.

CH: I think his songs about interactions, people’s interactions, are imminently relatable, and I think it’s the same specific details that he gives that make you go, “Oh, I know that feeling.” Those are still and always will be relevant.

He once described his compositions as “weird songs.” Where do you see them fitting in the greater tradition of folk?

RE: Especially in the context of the world he was in, he’s very weird. I guess everyone’s odd in some way, but he definitely embraced his eccentricities. Rather than shy away from something that’s really nuanced and John Hartford-y, he would embrace it. “Down on the River,” from an arrangement perspective, you have these weird, old-time fiddle lines, and it sounds like he overdubbed 20 tracks of them. It’s a huge section of fiddles. His instinct was to really be himself regardless of the context. I think that’s what drew both of us to him.

As far as themes, one thing I really like about his meaning and motive for writing songs is that he’s really careful to highlight beauty in the world rather than to call out specific things. You catch more flies with honey. Instead of going out and saying, “This is messed up! This is messed up!” he really shows someone how poignant a day of labor can be. A song like “Tall Building,” it’s not necessarily about how the city sucks. There’s this depth to everything he’s saying that’s much more fair and real-life to me, it’s not so preachy.

CH: I don’t know if he would have said it was protest songwriting.

Not exclusively, but I do think protest comes up in a rather sneaky way.

CH: Mmhmm, and I think it comes with a sense of tenderness.

RE: Exactly. It’s not that he’s softer; I just think he’s more honest. Life is this really nuanced, gray area most of the time, and I think songwriting has a bad habit of not allowing that. Instead of being the gray, uncomfortable feeling we all feel, songwriting tries to be very pointed and very one-sided. Writers like Hartford were comfortable being nuanced.

CH: And he wasn’t afraid to use humor and just be a weirdo in the way that he wrote. His ability to make people dance and his deep rhythmic groove and integrity … when people are dancing, you can’t help but listen to what someone’s playing, so songs like “Up on the Hill Where They Do the Boogie,” who knows what that’s about really. I think there are a lot of things that song can be about. Part of the gift of getting to play it for generations is to go, “Oh, maybe it’s about this. Maybe it’s about the hippies on the hill. Maybe it’s about the White House.”

RE: We were playing it the other day, and I thought, “Oh, maybe it’s about Capitol Hill, and you were like, ‘Well, yeah.’”

CH: I was like, “Duh.”

RE: That had never occurred to me. I had never heard it that way.

CH: The whole time I’m like, “This is such a political song.”

Hartford brought together banjo and fiddle for his compositions, whereas you’ve partnered your two guitars. How did you want to cultivate that particular sound while paying homage to Hartford?

CH: My first introduction to learning Hartford material was his fiddle tunes. I think one of the strongest components of his songs is to shape melodies, and to write really memorable melodies. Coming from playing fiddle tunes on guitar was a bonding place for both Robert and me, when we both came to this material. The first tune we learned together was “Delta Queen Waltz.” We thought it sounded really good; we had a lot of fun playing it.

RE: A lot of it, for me at least, was really intuitive.

It does seem that way watching you two play, but that makes sense, if it’s born of this friendship.

CH: We had two days to rehearse this material, but rehearse meant play it over and over again and learn it, and then we had two days to record, so it was all done in four days. We kept being like, “Dang, this is pretty easy,” because we both had similar instincts, so we didn’t have to talk about nuanced arrangement parts of dynamic because there was a deeper level of understanding, musically.

RE: It was really easy. All of it’s been really easy.

It’s nice when it works out that way. This is a weird question, I admit, but besides sounding beautiful, what did you hope your harmonies would achieve?

RE: I think there’s definitely a tension in the harmony thing that we’re doing on this record; I think we went for more of a conversation within the harmony itself because we are doing this thing as a duo. I don’t know. This is all subconscious. I think when musicians do interviews, a lot of the time they do things because it feels right and they do them naturally.

Right, and then they’re asked to think about them more critically.

RE: And then they have these grandiose explanations as to why. The harmony is having a conversation while the two of us are having a conversation, and I think it accidentally — in a good way — reinforces the lyrics of a song. If it’s a love song, then the harmony tends to be really sweet and beautiful and then, if it’s a song about tension in a relationship, we kind of leaned on dark harmony. I think it’s entirely natural that it happened that way. A lot of it is taking cues from the writing. Hartford already did a lot of the work in the writing.