Tamara Saviano admits she might have beginner’s luck. In 2001, she won a Grammy for Beautiful Dreamer: The Songs of Stephen Foster, which just happened to be the first record she produced. Fifteen years, two books, and three tribute albums later, she has received another Grammy nomination for Kris Kristofferson’s Cedar Creek Sessions, which just happened to be the first single-artist record she ever produced.

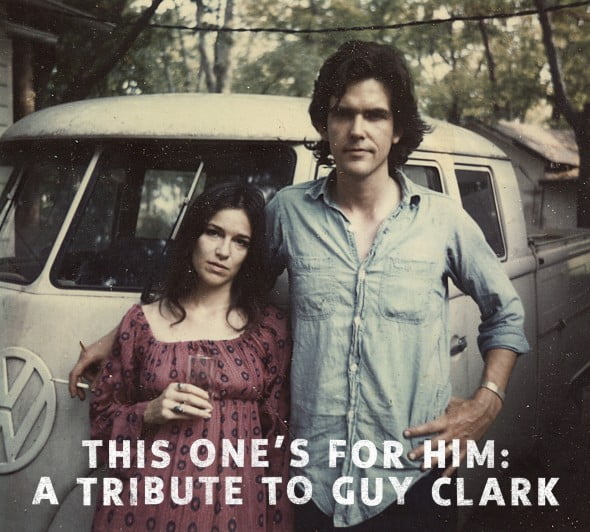

A singular figure in Nashville, Saviano works in the studio like any typical producer, twiddling knobs and convincing bass players they can get a better take. But it’s what she does outside the studio that distinguishes her. She builds albums from the ground up, starting with an idea and pursuing it until it becomes music. For Beautiful Dreamer, as well as for 2006’s The Pilgrim: A Celebration of Kris Kristofferson and 2011’s This One’s for Him: A Tribute to Guy Clark, she assembled the backing bands, scheduled the singers, assigned them songs, oversaw the sessions, determined the sequencing, approved the artwork, and in some cases even directed the promotional campaigns.

In doing so, she has become the foremost producer of tribute albums in Nashville, assembling compilations that are affectionately faithful to the honorees while also revealing new facets of their craft. Together with her recent biography of Clark, released in October 2016 and titled Without Getting Killed or Caught, her small-but-ambitious catalog constitutes a multimedia history of some of the country’s finest songwriters.

The Cedar Creek Sessions were a completely new project, even if the concept was similar: finding new life in old songs. It came together serendipitously, when Saviano found herself in Austin with Kristofferson and a handful of talented players, all with a few days to spare. Kristofferson recorded 25 songs in three days, drawing from his vast catalog spanning 50 years: some well-known (“Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down”), others not so much (“The Law Is for the Protection of the People”).

“He would just call out a song, and the band would start playing it,” Saviano says. “They were amazing, because they were learning things on the spot. For me, it was all about keeping the story centered: Who should be in the studio with him? Who should be engineering and mixing it? It’s all about telling his story.” By turns funky and melancholy, the double album shows a veteran musician who might be pushing 80, but has not lost a beat.

Still, she was shocked when The Cedar Creek Sessions was nominated for a Grammy for Best Americana Album — not because she didn’t think it was worthy. “I felt like I let that record fall through the cracks,” she says. “I run his label, KK Records, and I do most of the administrative stuff for him.” But both her mother and Guy Clark died from cancer in 2016, “so I spent most of the year sitting at somebody’s deathbed.” Still, she managed to get that album out to fans and publish her Guy Clark biography. When the Grammys were announced, “I almost fell off my chair. I think it spoke to people because it just captured this moment in his life.”

In March, she will release her latest tribute, Red Hot: A Memphis Celebration of Sun Records, which gathers a handful of Bluff City musicians to cover songs recorded at Sam Phillips’ legendary studio.

Your job is very different from what a lot of producers do. Do you see yourself in that role?

I think you’re right. What I do is different, even with this Kristofferson album, which is the first time I’ve produced a record by one artist. I approached it the same way I do my tribute albums. I got a house band together to play live in the studio, and then brought Kris in. He sang through 25 of his songs in three days. We did everything live, although we did end up sweetening some of it. But I never think about that when I’m in the studio. Really, it’s all about the live performance. That’s how I’ve done my tribute albums for the most part. Beautiful Dreamer was different because it was the first one. We had a band for some of the tracks, and some people turned in their own tracks. I learned on that album that I didn’t like people just turning in their tracks, because then I had no creative control. Working with a house band means there’s some consistency in the sound, which is the way I like to work.

I’m assuming that makes scheduling a headache.

It is. It’s like herding cats. But it’s so important. When we did Beautiful Dreamer — which I love and we won a Grammy and everything worked out — there were a couple of tracks that were turned in, and I just didn’t feel like they fit with the other tracks. Making the entire album work together was more challenging, and it wasn’t as much fun. It took some of the magic out of it. I realized that I didn’t want to do it that way. I want to schedule artists. It’s not always easy. We had to lay down tracks for Rosanne Cash and Willie Nelson on the Guy tribute. I just couldn’t make the scheduling work, so I had my band lay down the track and they added their vocals later. I don’t like to work that way. It’s better to have everybody in the studio at once. Like Lyle Lovett on the Guy tribute. He’s such a perfectionist, so it was amazing to watch him work. We were in the studio for a long time to get one song, but to be there with the artist and learn how they like to work and watch them give direction to the band is a great learning experience for me.

Are you using the same band for each album?

I pick musicians based on the project. With the Guy tribute, I wanted Shawn Camp and Verlon Thompson and Lloyd Maines in the band, because they all had personal relationships with Guy. Jen Gunderman played keyboards on it. We recorded half the album in Nashville and half in Austin, which was important to me, too. In Austin, we had Glen Fukunaga on bass and John Silva doing a little bit of percussion. We had a couple of bass players in Nashville because it didn’t work out to have just one. But yes, I do pick the band based on the project, based on who I think is going to hit the sweet spot of those songs.

So it’s not just the musician’s skill or technique, but the personal connections they have with the music.

You know, I still think of myself as a writer and a journalist first. I’m telling a story, and every part of it matters to me: the photos and the artwork and who’s in the studio and who’s writing the liner notes. I just did a Sun Records tribute with Luther Dickinson that’s coming out in March, and I had Alanna Nash, who has written several books on Elvis, come into the studio with us so she could write the liner notes. I wanted her to be there so she could get everything that was going on. She’s telling the story of the music that goes with Sun. I do that with all my projects, too. I don’t think a lot of people have the liner note writer in the studio, but I prefer to do that.

How did the Sun project get started?

I wish I could say it was my idea. It wasn’t. I thought I was finished producing tribute records, but there’s a new organization called the Americana Music Society of Memphis and they were fans of my Guy Clark tribute. They approached me about doing an album that was very Memphis-centric. I love Sun Records. That was what I cut my teeth on. Even though I grew up in Milwaukee, my first taste of music was that stuff. My dad was really into that stuff: Sun and Stax and all the Memphis music. Because I’m not from Memphis, it felt a little inauthentic for me to do this, so I brought in Luther. His dad was Jim Dickinson, and he grew up in the area. He has such a deep well of knowledge about the area, so I brought him in to co-produce with me. We put together a house band — all Memphis people — and we did it at Sun and Sam Phillips Recording. It was probably the most fun I’ve had doing a tribute album. It was amazing being in those historic studios with the ghosts of Sam Phillips and Johnny Cash and Charlie Rich.

How are you matching the artists with the songs? Do they get to choose, or do you — as the producer — assign them their covers?

Before I started calling artists, I spent a long time listening to the Sun catalog. And here’s something I learned during that process: Some of the stuff I was listening to was later Sun material that Sam Phillips had nothing to do with. So I had to decide: Are we going to stick to the Phillips era or cut some of the more modern stuff? And we decided to stay true to the Sam Phillips era, and that changed which songs were available. I sent a couple of ideas to the artists — Amy LaVere, Valerie June, Bobby Rush, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Jimbo Mathus. Who am I missing? They all either grabbed on to one or we had further conversations about what they might want to do. I really wanted Luther to do a blues tune. I picked out a couple of really old blues numbers for him, and he ended up choosing Howlin’ Wolf’s “Moanin’ at Midnight,” which turned out great.

Also, CMT has this new history of Sun starting next quarter, with actors playing Jerry Lee and Johnny Cash. Chuck Mead is the music director for that show, so I had him come in and bring in the actors who could really sing. They all did “Red Hot.” It was a lot of hoops to jump through, but I knew their TV show was going to start right around the time the record comes out and I thought it would be a fun tie-in. With Chuck, I was trying to think about what song he could really work with, and it just so happened that one of the songs they were doing in the show was “Red Hot,” so I thought, “Let’s just do that.”

For the Sun tribute, I gave the artists some ideas, but they all made the final decisions on their own. But with the Guy tribute, I was the one picking the songs. I didn’t leave much room for negotiations on that. Because I knew Guy’s catalog so well, I heard certain artists singing certain songs. He has this song called “Magdalene,” which is one of his newer songs. I just love it, and the only person I could hear doing that song is Kevin Welch. I asked Kevin if he would do it and he agreed. I love everything on that album, but that’s one of my favorites. He really made the song his own.

How does your understanding of people like Guy Clark and Sam Phillips change during that process?

Being a journalist, I tend to do a lot of research, so before I even go into the studio, I know so much about the songwriter and their work. So the recording of the music is just a continuation of that story. When we did Beautiful Dreamer, I had just started this nonprofit called American Roots Publishing with David Macias. It was his idea to do that album, and I thought certainly somebody had already done a Stephen Foster tribute. We looked and there was nothing that was Americana folk. It was all orchestral. So, before we started recording, I went back and listened to every Stephen Foster thing I could find. I went to the Stephen Foster Memorial Museum at University of Pittsburgh and looked through everything. I knew the same songs everybody else knew, but I just wanted to know more about him. He was the first professional songwriter in America that we know of. How did that happen? There was no recorded music or radio. It was all sheet music. But somehow “Oh, Susanna” made its way from the East Coast to the California Gold Rush. I wanted to know that story before we started recording, so that I was emotionally attached to Stephen Foster by the time we started laying down those songs.

Working on an artist who has been dead for 140 years must be very different from working with an artist like Kris Kristofferson, who is still alive and kicking.

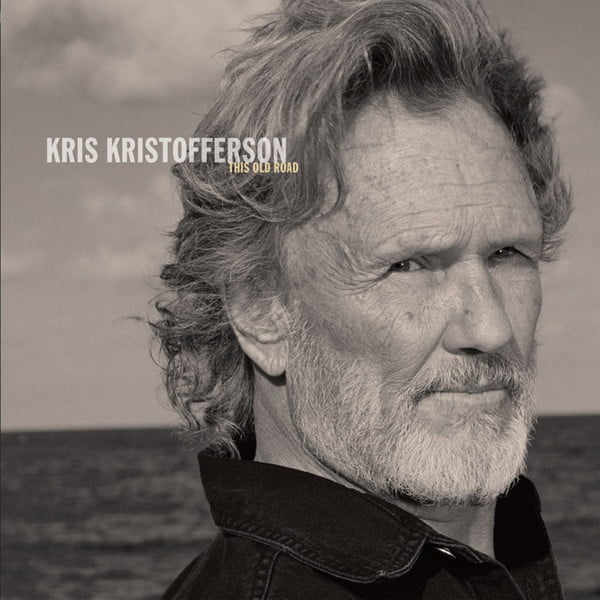

Beautiful Dreamer was more of a history lesson, but the Kristofferson tribute was much more personal. We did that for his 70th birthday, which was 10 years ago. That was really my birthday present to him, so I wanted him to love it. Even though I had worked with him and know so much about him already, I went back and read everything I could get my hands on. I talked to Kris over and over, just kept asking him questions about the songs he had written, what he liked and what he didn’t like, what he wished he had done differently. Unlike Stephen Foster, he was somebody I could call whenever a thought popped into my head. By the time we recorded, I had a much richer understanding of him as a songwriter.

I remember when I got the final CD. We were shooting a video in the Mojave Desert for a song on This Old Road. We were sitting in this SUV, and I pulled out the final CD to show him. It has a photo of him as a young man, and the first line in the song “This Old Road” is, “Look at that old photograph, is that really me?” And that’s what he said when he saw the CD. “Look at that old photograph, is that really me?” And he started crying. I should mention that Kris does cry. He’s very emotional.

This is something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, with all the obituaries for George Michael and Carrie Fisher. I read these beautiful sentiments about how inspiring these people are, but it’s only after they’re dead. I started wondering why we aren’t saying those things to people when they’re alive. Obviously The Pilgrim isn’t the same as an obituary, but it serves a similar function.

Those of us who are music geeks know all about Kris’s songwriting catalog, but I don’t think many people know just how deep it is. I found this out working with him, but a lot of people know him as an actor. Of course he’s a great actor, but his real gift to the world is his songwriting. So it was great to honor that aspect of his life. It was the same thing with Guy. We were talking one day and I thought, “I have to do a tribute album while he’s still here.” And I think that made my biography better.

How so?

I was already familiar with Guy’s catalog from working on the book and just being friends with him, but I hadn’t really been in the studio with him. I had gone in a couple of times when he was recording, and I knew about his recording process a little bit. When I decided to do the tribute album, I decided that I was going to use the same recording process that Guy used. That really was my baby, so I knew which artists I wanted, which songs I wanted them to do, and I knew how I wanted to record it. I wanted to walk in Guy’s footsteps, doing things the way he did them and getting to know his songs in a different way — from a recording standpoint rather than just a listening standpoint.

Even though you have a plan whenever you go into the studio, you don’t know what’s going to happen. You’re creating everything on the spot. You’re recording live with a band, and the musicians are learning the songs at the same time that they’re recording them, and it’s a creative moment in the studio. I love that. I love when I have no idea how it’s going to sound, and then a couple of hours later, there it is. It’s a song that I already love because I love Guy and I love his version, but here’s this new version with a new singer. Here’s Lyle Lovett doing “Anyhow I Love You.” Here’s Shawn Colvin doing “All He Wants Is You,” which Guy did from a male perspective and now it’s a female perspective. And then Rosanne Cash doing “Better Days.” That was very important to Guy. He actually stopped singing that song after he wrote it because he didn’t like this one line in it. A few years later, he finally wrote a new line that he liked, so when it came time for Rosanne to record it, Guy called me at least three times to make sure she sang the new line. In his mind, the songs were never really finished.

And it sounds like you’re never really finished working with these people, either. I heard that you are working on a documentary about Guy Clark.

I started working on it in 2014, but last year I didn’t do a thing on it because my book came out and, like I said, my mom died and Guy died. So that will be my first priority in 2017, getting back to work on that film.

For more insight into the producer’s mind, read Stephen’s interview with Buddy Miller.