An interview with Rhiannon Giddens these days feels like a game show lightning round. Since winning the Steve Martin Banjo Prize in 2016 and a stunning $625,000 MacArthur Fellowship in 2017, the songwriter, singer, and instrumentalist has widened her scope and let a range of fine and folk arts projects flood into her idea-driven world. When we caught up with her in Nashville, for example, she was in rehearsals for Lucy Negro Redux, a multi-layered original ballet about Shakespeare, his purported black mistress and issues of identity and otherness. Working with poetry by Caroline Randall Williams, she composed the music with one of her latest collaborators, jazz pianist and world percussionist Francesco Turrisi. They’ve made a duo album set for release this year.

Here, Giddens speaks about her broader artistic scope and her attention on how women of color negotiate the past and present.

How different is your creative life now versus five years ago?

Oh my god. It’s like: “Who was that person?” I don’t even know. I am so grateful for that time. I was transitioning from the Carolina Chocolate Drops to my solo career. But it’s definitely become more of a creative life. I still am very much an interpreter. I’m very interested in giving old songs new life and putting them through a lens of today and I think there are a lot of things that are left on the shelf that need to be aired. But I definitely have found over the years that I’m finding more and more of my creative life to be in writing and collaborating. I’m very rarely going to sit in a room and write stuff. It’s like I write things and then I want to work with somebody and develop them or have a reason to do it.

So my collaborative opportunities have really grown since I left the band because it’s a lot easier to do things as your own person. There are all these things you have to think about when you’re in a band that I don’t have to think about any more. And it’s really allowed me to focus on the woman side of things, which is hard to do when you’re in a band full of boys, you know? Now I feel I can focus a bit more on what I’m finding is very important and front and center for me, which are women’s issues and women of color, in particular. Dealing with the history of what we’ve had to go through in this country and in other places, and what does that mean? And creating platforms for other women of color to have their voices heard, in my limited capacity.

You have background in opera, which may be the most collaborative of all the fine arts, with all its component parts. And you’ve started doing Aria Code, an opera podcast. What’s that about?

I was approached by Metropolitan Opera to be guest on this podcast and it just turned into becoming the host. And that’s been really fun. The wonderful producer Marrin Lazyan, she’s put it all together and I’m there to provide context and if there’s stuff that jibes particularly well with what I know like Otello, the Verdi opera, I can bring in my expertise on blackface and things like that. It’s been great.

And I’m going to be in my first production next year as a mature artist. I’m doing Porgy & Bess with the Greensboro Opera. It’s to open up the new arts center in Greensboro. So it’s kind of part of my involvement in my hometown. And also an opportunity to sing Bess, which I’ve never been able to do. So opera’s come back into my world in kind of unexpected ways. I’m writing an opera. I sing with orchestras on a regular basis. So it’s been really wonderful to see that come back into my life because it is something that I love so much and that I have spent a lot of my years doing. So we’ll see where it goes. I don’t know!

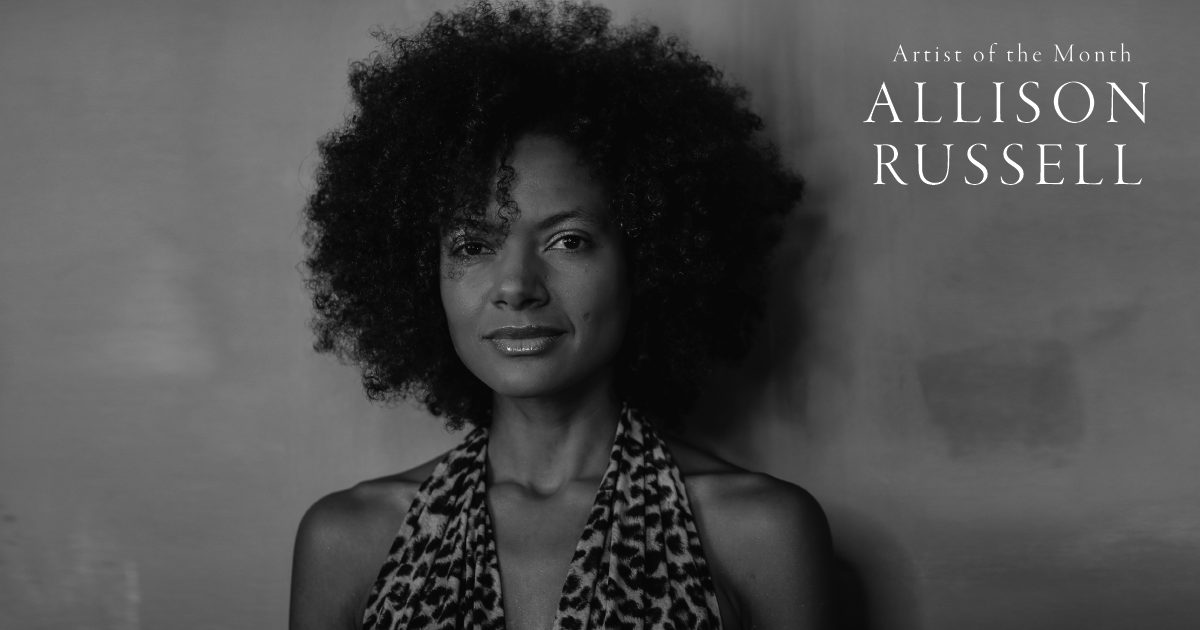

You produced the album Songs of Our Native Daughters, which brings you together with Amythyst Kiah, Allison Russell, and Leyla McCalla. What motivated this and how do you put these women into context?

It was an amazing opportunity. I was already working on this idea of early American musical history and speaking to it through the music of the banjo and the music of minstrelsy for Smithsonian Folkways. So it took this little turn and became a record with these really strong women of color. With my co-producer Dirk Powell, we were talking about who we wanted to be on this project, and that’s where we ended up. I was like, “Oh, this is where it needs to go.” From then on it took this slightly different path down to really talking about the woman of color’s experience in America and having a platform to respond to that in an artistic way.

And to each of the women who came in, I said, look, bring your banjo. And let’s talk about what it means to be a woman of color here and what it means to have ancestors who’ve gone through what they’ve gone through. It was an amazing experience to watch them feel like they had this space to write about these things that maybe they’ve touched on, but to have days to focus on these themes and these ideas. It was a beautiful collaborative thing. I’ve worked with each of them in various ways so I just knew it was going to work. And it worked better than I could have ever really dreamed. It went places I’d never have considered. That’s why you pick people and then you let the project do what it does instead of going, “It’s not exactly what I envisioned.” Well, usually because it’s better! So leave it alone and let it do what it’s going to do.

In this respect, do you see yourself as a mentor, or as a leader in this widening and overdue effort to infuse folk and roots music with more voices?

I’m always looking for ways to facilitate. People in these positions, like the folks putting on the Cambridge Folk Festival or at Smithsonian Folkways, they’re looking to me, and I’m like, “Hey these people, because they’re awesome.” And if that’s how I can use whatever little power I have in the world, that’s what I want to use it for. I’ve got my own career and it’s very important to me, but that’s also very important to me–creating the community of people that are doing this.

Because that was the strength of the Carolina Chocolate Drops. We were a band and we had each other. In a time where, even less than now, people were like, “Black people on banjos? What?”, we had each other and I know what that community can mean as an artist. It really gives you strength. And that was my idea with Our Native Daughters and with anything I’m (doing). Amythyst has opened for me. Leyla was part of the Chocolate Drops. JT and Ally (Birds of Chicago) — I’ve definitely championed them. I think that’s what we need to do for each other. If I’m in a position where somebody who has power asks me, I’m going to spread that around. Because I think that’s what you’re supposed to do.

They tell writers that it’s better to show than to tell. And it strikes me that roots music is moving from a phase of ‘telling’ about inclusion to a phase of showing. Is that fair to say?

I think so. I’m definitely moving that way in my own life. There was a lot of talking with the Chocolate Drops because you had to educate people. But there was also a lot of just doing. We found the balance; we’re going to contextualize this, but then we’re just going to play it. Because the facts are the facts and we’re not in a position to shame you about not knowing this. We didn’t know this. But I definitely found that over time, I’m tired. I just want to play and sing.

And the next record of mine is not a project. It’s not a mission. It’s coming out in May (I think) and Francesco and I did that together. It’s really all the worlds that I’ve been talking about and being in all together. I just want somebody to put it on and listen to it, and they don’t know anything about me, and they come away – I want them to love the record but I also want them to feel this aspect of nobody owns any sounds. Nobody owns any experiences in humanity. We’re taking all the sounds you heard in the ballet and the notion that humans have been moving since the beginning, and we’ve been affecting each other since the beginning.

So a religious trance drum from Iran works perfectly well with an Appalachian a cappella ballad. Because they’re representing universal human truths. It would be really nice for people to just experience that through sound and through the experience of the songs. And of course we’ll talk about it. But I’m kind of moving toward showing and inhabiting all the work that’s come up until now and living in that and taking that to where it needs to go.

Craig Havighurst covers music for WMOT Roots Radio. Hear the interview.