As the first solo blues artist signed to Fat Possum Records in 20 years, Buffalo Nichols faces high expectations. But on his self-titled debut, the musician (whose given name is Carl Nichols) more than meets them, stitching Black history and musical traditions with current events and experiences to craft the sonic equivalent of a quilt. And the story it tells is an important one.

Nichols was born in Houston and raised in Milwaukee, but when he got the urge to roam and the money to do it, he took off, immersing himself in creative scenes across Europe and West Africa. Although he’s been based in Austin since the fall of 2020, Nichols channels the Delta, North Mississippi and Chicago through his nimble fingers or resonator slide while wrapping his warm voice around words that cut to the core of oppression, and the many forms of heartbreak it causes. While the poetic lyrics in songs such as the sad, beautiful “These Things” might be open to interpretation, there’s no mistaking the point of “Another Man,” adapted from the chain-gang lament, “Another Man Done Gone”:

When my grandpa was young

He had to hold his tongue

‘Cause they’d hang you from a bridge downtown

Now they call it ‘stand your ground’

Another man is dead.…

No need to hide behind a white hood

When a badge works just as good

Another man is dead…

It’s a protest song for today — clearly connecting the dots that for Black people in America, as the song says, “it might as well be 1910, killing women and killing men.”

BGS: Do you remember when you discovered blues music?

Nichols: I guess I discovered it as a genre when I was 12 or 13, through my mom’s music collection. She had the stuff that everybody had in the ’90s: Robert Cray, Strong Persuader, and that Jonny Lang album (Lie to Me); stuff like that. For the most part, I skipped the blues-rock thing. That was never of much interest to me; I went from contemporary blues straight to country blues and folk blues.

So how did you get from Milwaukee to West Africa and Europe?

Airplane.

Thanks for the smart-ass Greenland answer.

(Both laugh.) I didn’t travel much as a kid or into my teens. When I finally had the money and independence to do it, I decided to go as far as I could. That’s where I ended up.

And how did your travels help you find this path you sought to connect the Black experience, as expressed in early blues, to Black lives today?

I just saw a respect for Black art and Black culture that didn’t exist, and still doesn’t exist, here. And it is upsetting, but I just felt like, if there’s something that can be done about it, even if it’s futile, it’s still worth trying. I saw so many people in Europe making a living off of (music), and in Africa, really living and dying for it. So I felt like I could contribute in my own way.

The lyrics in “Another Man” are particularly chilling, and quite effective, I think. Listeners tend to assume lyrics are autobiographical even when they’re not, but the lines “Police pulled a gun on me. I was only 17” sure sound like they come from actual experience, especially in a place like Milwaukee. Is that a fair assumption?

Yeah. That is fair. “Another Man” is an older song that came from a time when I mostly wrote autobiographically, when I was deeply immersed in — or at least trying to be immersed in — the folk and Americana world. Ironically, the reason why I felt like leaving that and going to the blues is because I got really tired of this sort of outsider perspective, like trying to explain my humanity to a bunch of white people. That’s what Americana was, and still is, to me. So I stopped talking about myself so much, because I felt like my experience should be valid enough without the trauma. They really love that stuff in Americana. In the blues, it’s not much better, but now I make more of an effort to write stories and not always write about myself.

I’m sorry that you felt invalidated in those genres. Country and Americana … a lot of these genres are trying to be more inclusive, but sometimes it feels like they’re forcing it. Where’s the balance, and how do we find it?

As far as I can tell, so much work has been done to keep it this sort of white-boys club, that any effort for inclusivity is naturally going to be forced. Until there’s this real structural change, the same people who made it what it is are just going to be cherry-picking which voices they allow to break through every once in a while. It doesn’t feel natural; it feels … like it’s all been sort of orchestrated from behind the scenes.

I guess if it feels forced now, maybe one day it won’t. Going back to the music, there’s a really elemental sound to these songs. A lot of them are just your vocals and resonator. When I saw you live, I noticed a lot of effects being added that aren’t on the album. What’s the decision behind that?

I had a more ambitious idea of what I wanted to sound like, and I didn’t get to do it on the record, so I try really hard to be more creative live.

I think it’s a great album, but I can understand if it doesn’t express your artistic desires, why that might be frustrating.

That certainly ties into my gripes with Americana. Everything is like, “Oh, this is great progress.” But at the end of the day, the people who orchestrated it are the same people who kept us out of it.

When it comes to authenticity in blues, do you believe race makes a difference?

I think it does. I mean, I’ve been hearing that word a lot, authenticity, and I don’t even know what it means anymore. Obviously, it’s complicated, but … there’s so much about the blues that I don’t even understand, being born in 1991 and being raised in the Midwest. And it takes me a lot of conscious effort to — you know, part of it is this real ancestral connection that I feel, and part of it is stuff that I have to learn like everybody else. But I really think that white people are so far from the actual music and the culture of it that I just don’t understand; I mean, it’s great music, but white people can do whatever they want and be anything they want. I don’t know why you would want to be a depressed Black person. (Both laugh.)

A blues scholar I really respect told me that one reason it seemed like Black people gravitated away from the blues is because it was the music of a depressed culture, a time of oppression, and hip-hop is music of aspiration.

I think that’s a myth. Hip-hop and the blues both cover the entire — I mean, I jokingly say it’s depressing, but both cover every aspect of Black existence, the joy and the darkness. There are a lot of theories on why Black people moved away from the blues. But I think a pretty good example is somebody like Elvis, where the music industry found a way to make the music without the people, and when people don’t see themselves in it, they look for something else. I think that’s really what it is. You can even see it in real time. When things get commodified, regardless of race, the people who create the culture feel like, “OK, now we have to move on because it’s not ours anymore.”

Well, how do you respond to that? Is there any way that makes sense?

I really don’t know. Some of my peers are a little further ahead of me, but Kingfish (Christone Ingram), Adia Victoria and Jontavious Willis, everybody’s doing their part. But we’re also scrambling around, figuring out how do we, in this limited time on this earth that we have, carry on this tradition that these people dedicated their lives to and went through hell to preserve, this little piece of culture that we are able to make a living off of. I think the best thing we can do is just keep creating, because each one of us is going to inspire one or two or three artists to take on that burden and turn it into something that we’re all proud of.

Every time somebody says the blues is dead, there are always people who seem to be picking it up. Maybe it goes in and out of popularity, but it doesn’t feel like it’s going away; at least, I think people who want to find it are still always going to find it.

It does kind of go in and out of fashion — and people make a bigger deal out of it than they should, because this music predates the music industry. It doesn’t have to be profitable; it doesn’t always have to be in vogue. It is a genre, and there is an industry surrounding it, but it also is a cultural art form. It doesn’t need anybody’s attention to be valid.

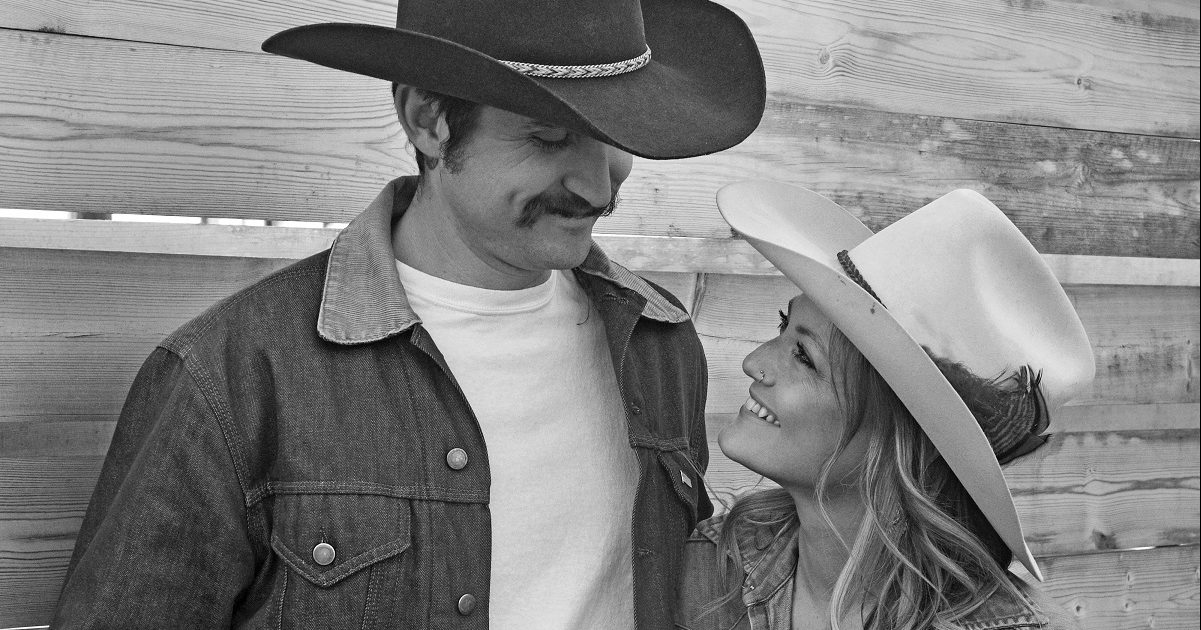

Photo Credit: Merrick Ales