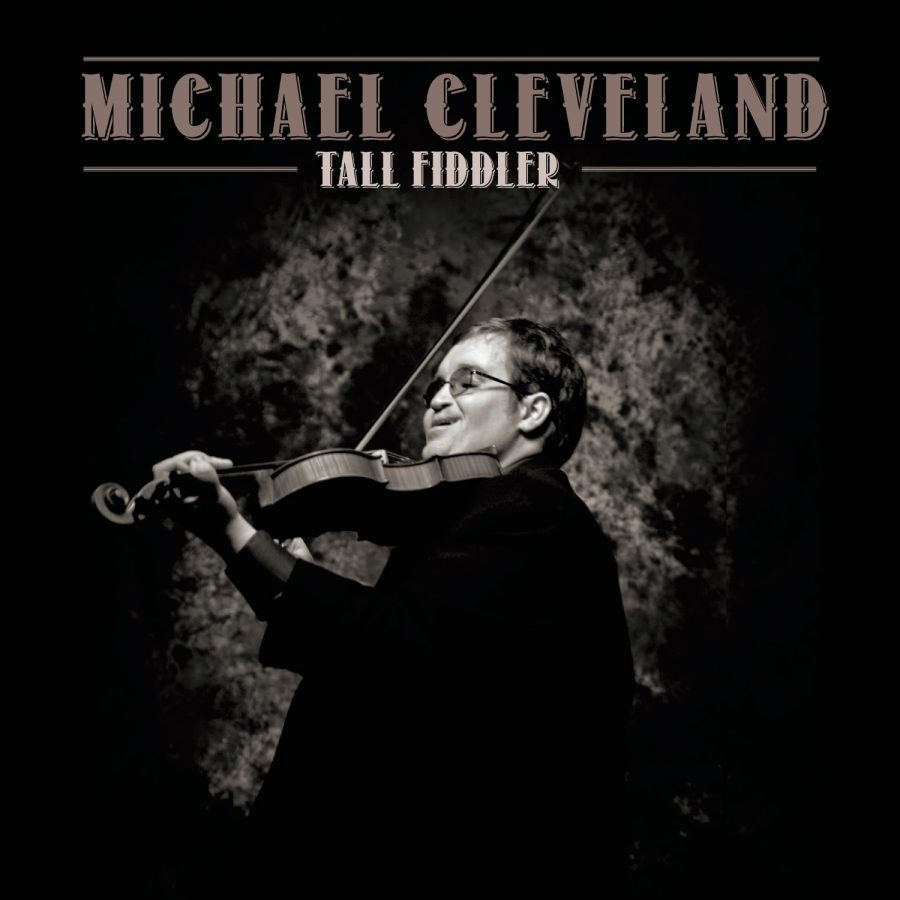

Yes, Michael Cleveland’s brand new album, Tall Fiddler, includes a track called “5-String Swing,” and yes, perhaps the world’s foremost banjo player, Béla Fleck, is a guest on the song, but do not be fooled. This is not a banjo tune, this is is not an incendiary breakdown or a Scruggs-conjuring, “Foggy Mountain Special”-esque number. This is a fiddle tune. A five-string fiddle tune.

An eleven-time winner of IBMA’s Fiddle Player of the Year award (and current nominee for what may be his twelfth honor), Cleveland’s “ax” of choice has long been a fiddle with five strings — instead of the standard four — with a low, C-tuned string beyond the usually-lowest G string, essentially combining a viola and a violin on a violin’s frame.

In more standard, traditional bluegrass that fifth string doesn’t always jump out, but in a song such as this — skipping, gallivanting swing with a touch of Texas and a dash of Django bolstered by bluegrass — it can change a fiddler’s entire mindset, leading them toward sumptuous, lush double and triple stops that defy any sort of quantification. Cleveland is well known for milking these jazzy harmonies, leaning into quarter tones that no fretted instrument — and very few other fiddlers — could ever accomplish with such exact, scientific precision.

Besides Fleck, and his similarly innovative approach to combining rootsy aesthetics, Cleveland is joined by producer Jeff White on guitar, Tim O’Brien on mandolin, and Barry Bales on bass, perfect pals with which to swap licks over this cheery, energetic, toe-tapping tune.