Comprised of singer-songwriters and instrumentalists Vivian Leva and Riley Calcagno, Viv & Riley are an up-and-coming musical duo that defy definition. Their new album, Imaginary People, is a masterful blend that weaves together their shared reverence for traditional Appalachian music alongside indie-folk, pop-leaning adornments. The result is an emotionally potent 10-track album that covers a vibrant range of personal and universal truths — from the bittersweet nostalgia of visiting a beloved childhood hideaway decades later, to the poignant curiosities that accompany reckoning with climate grief.

Based out of the dynamic music scene in Durham, North Carolina, this duo is currently on tour across North America. With their insightful explorations of the past and creative probings of the future, Viv & Riley uncover rich and complicated explorations of what it means to be alive in this precise moment.

So how did the two of you first start making music together?

Vivian Leva: Well, we first started making music together when we first met in 2016, the summer after we both graduated high school. I grew up in Lexington, Virginia, and Riley grew up in Seattle, Washington, and we just happened to meet at a camp in Port Townsend, Washington. It’s one of those camps that has weeks back to back — there was a vocal week that I was teaching with my mom, and then Riley came to teach fiddle the following week. We happened to overlap by a few days, and Riley was there with his band The Onlies. The first night we met, we played music together all night! After that, I joined the band, and we also started playing together as a duo and writing songs.

Riley Calcagno: The origin of our sort of band, our duo, came later that year, in the fall. We had been communicating and texting some music back and forth, and then Viv invited me down to Asheville to play a gig with her and her dad. I was a fan of her dad, James Leva, for his fiddle and singing, so we did that gig. But we thought it’d be also fun to try out some duo material while we were down in the same place, even though we had never played songs just the two of us. We emailed a venue in Asheville called Isis Music Hall, which was a prominent venue there at the time. Somehow they slotted us in, on a Wednesday night, into this big hall that they had — 200-person capacity, maybe bigger. We had never played music together going into that, but we put together some material and we enlisted some friends to play with us. It was a bold move! Talk about faking it until you make it. Only about 15 people came out to the show, and I’m sure it sounded terrible. But it was fun!

That sounds amazing. So how would you describe your musical chemistry? What is it like playing together?

VL: Well, I think our initial musical chemistry initially came from our shared background in old time music and traditional music. That first night that we met, we played a lot of fiddle tunes, old music, and traditional songs. So it kind of began from a place of excitement about being exactly the same age, having never before met, and somehow both being raised around this same music that we have a shared respect and love for. So that was the initial spark of actually finding another young person who’s into the same niche genre and community. But since then it’s totally stretched into other realms. We are both so open to other kinds of music, and we have very similar tastes and aesthetics. It’s very easy to create music together because we come to it from a similar place.

RC: One of our dynamics in making music together has also been sharing our individual strengths with the other person. When we first started playing together, I couldn’t really sing harmony or find a harmony part. Vivian was very patient with me and helped me learn, and I still feel like I’m getting better all the time. That’s exciting!

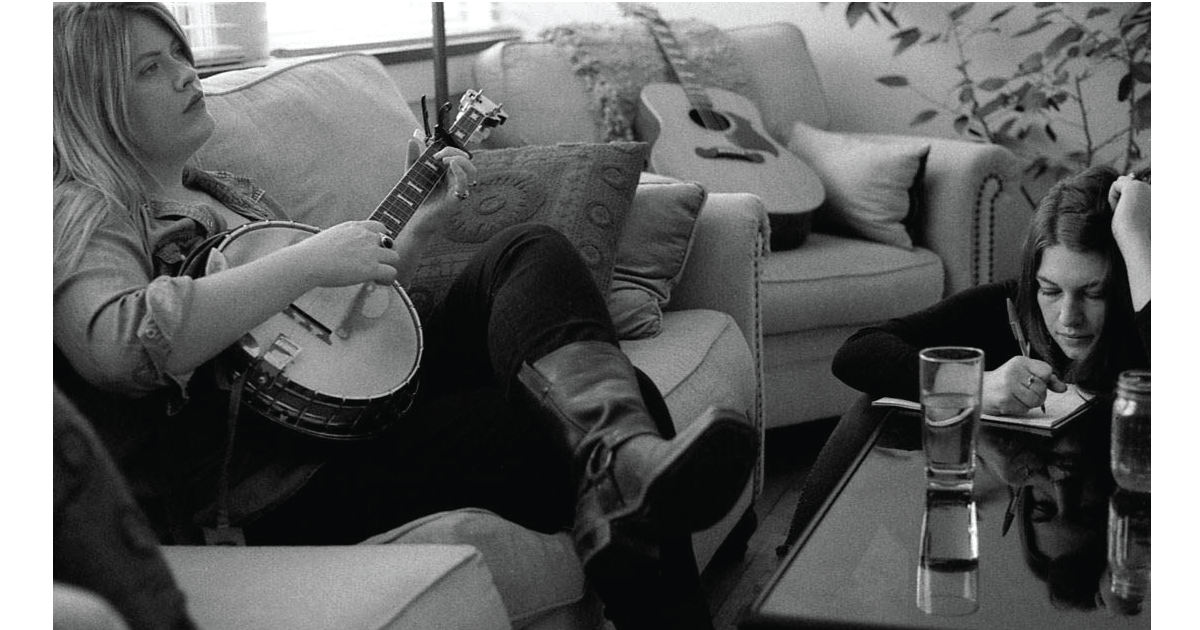

VL: I just play guitar, and Riley plays every other instrument. He’s a great fiddler, guitar player, banjo player, mandolin player— instrumentally he brings so much to the table. And I feel I bring a lot of singing and songwriting-focused material to the table. We stretch each other, fill in the gaps for each other, and learn from each other.

What a beautiful thing! So what do you each feel like the biggest difference in your respective musicianships is?

RC: Viv is a very natural musician. She grew up traveling around with her parents as they toured, sitting in on harmonica at her dad’s gigs when she was only three or four. I also was born and raised around music, but it was a bit more formalized, whereas Viv’s music just comes very naturally and it’s not forced in any way. She does what she does super well and consistently and steadily, and I’m a bit more erratic. I take chances and get obsessed with things and take big leaps that sometimes fall flat. Every time she steps on stage, Viv can knock out a great performance, and I feel more streaky.

VL: But he tries lots of different things! And like he mentioned, Riley has a more formal background in music. He took lessons, he learned how to read music, he knows music theory, he did classical violin. So I think a big difference is that he technically knows what’s going on, whereas I don’t have the language or skills that he has. I’m definitely more intuition based than technically based.

You really balance each other out! So your new album, Imaginary People, just came out on September 15, and I’m wondering how your songwriting, as it appears on this album, has shifted since you first began as a duo.

RC: Well, in the past, before we started writing music for this record, we were living in different places so it was a lot of collaboration from afar. A lot of the songs on our last record came from texting voice memos back and forth. And you know, it’s not utterly different to work on them in person, but some of these new songs came out playing them together in the moment.

VL: Another big difference is Riley has started writing way more. So I think there’s more of an equal voicing on this record than in the past. There’s more of his perspective in it. And I think now that we’re living in the same place it’s also allowed us to write about a more diverse range of things. We’ve written a lot of intense emotional, romantic songs in the past, but in this recent past couple of years, we’re more interested in other things, like our shared experiences about other parts of life.

RC: And it’s also partly stylistic. Our last record was pretty much a country record. During that time, I was listening to a lot of classic country music, and this time we were listening to a wider range of things. Having a broader array of influences definitely helped us push the narrative forward.

What are you each proudest of on the album?

VL: I think what I am most proud of isn’t a specific track or anything — mostly it’s this feeling that I unlocked something. I think I let go of some fears in the process of making this record. I felt more free to just say yes to trying new things and became less concerned with things like what genre it was going to be considered, or if the people who liked our last record would like this record… and so on. I stopped worrying about categories like, “This doesn’t sound traditional enough,” or “This isn’t country enough,” or “That’s too rocker or indie.” Instead, I was able to adopt the mentality of “Hmm, that sounds interesting, let’s try and just do what feels fun!” I think I’m most proud that I was able to do that. It felt amazing to take things a little lighter and to roll with ideas that felt a little outside of the mold.

RC: When you start making music, being young musicians, you get immediately labeled. It’s not something that I think either of us necessarily anticipated, but when that first record got classified, people said it was Appalachian and classic country. And then the next one was classic country and Americana. Like “Hits-the-Spot Americana,” whatever that means. And I think there’s an urge for musicians, when you get labeled as something, to keep reproducing it. There’s this toothlessness to the modern Americana music label— it’s the creation of music that is literally meant to sound like other music under a category. I don’t have a problem with genre or specifications, I think it’s oftentimes useful, but it’s [useful] when you’re trying to reproduce sounds so that you can cater to an audience, it’s like you’re trying to sell something in a market that’s already been created. I think that can be the “dampification” of art. And while I think there’s been so many amazing things created within the Americana industry, I also think it often leads to less creativity and less interesting music.

Coming out of our last record, we had some buzz in the Americana world, and it would have been easy for us to make another “Hits-the-Spot Americana” record. But I don’t think that we did that, and I feel proud of that. Like Viv was saying, we didn’t just do what we were supposed to do. You know, there’s synthesizers, but there’s also a fiddle track, and personally, I think it all works together. So maybe if you’re an Americana devotee, you’re not going to love this album, but that’s okay with me. I think there’s a power in making an album that the machine doesn’t really know what to do with. The machine can make up albums and spit them out, but I feel proud that this one isn’t something that can just be spit out because of how we combine traditional and non-traditional music. For example, there were super organic moments where we all stood around one mic and sang together, coupled with other moments where we had things locked in, produced, and added synths because a particular song called for it. Making those two things coexist in the same ecosystem was definitely a challenge, but listening to the record, I think it all makes sense together.

It’s an album full of teeth! Now, before we wrap up, I have to ask: you’re our One to Watch, but who are you watching right now? Any creatives, musical artists, or otherwise that are inspiring you right now?

RC: One is our neighbor in Durham, North Carolina, Alice Gerrard. She’s almost 90, and she’s putting out a record on this indie label from the area called Sleepy Cat. She’s collaborating with a bunch of young people and their art for the record, like making these amazing videos. It’s a really cool thing! People around here are really conscious and thoughtful about aesthetics and sound and ethos. Everything is done with integrity, so it’s a cool scene around here in that way. Alice makes amazing music, I’m really excited for her upcoming record — I think we’ll all be glued to it once it comes out. Another one is our friend who we wrote two songs with on our previous record, “Love and Chains” and “Time Is Everything”— often people’s favorite songs of ours. I just had the honor of producing his upcoming record under his band’s name, Preacher & Daisy. I love the music, so I definitely want to give them a bump! The fun thing is that all this music is sourced locally from the Durham, North Carolina area, where we’re based.

VL: Some folks I’m enjoying listening to right now, not that they’re not already being watched, are: KC Jones, Canary Room, Dori Freeman, Alexa Rose.

Photo Credit: Libby Rodenbough