Bruce Springsteen. What, really, is there to write about him that hasn't been written thousands of times? (Although this ranking of all his songs is awfully cool!) He's a working-class hero, a thinking-man's poet, an activist-artist, a national treasure, and a songwriter's songwriter with 18 albums and millions of record sales to his credit. Over the past five decades, Springsteen has witnessed and documented in song the American dream — its promise, its realization, and its demise. For that, he can also be credited as an oral historian.

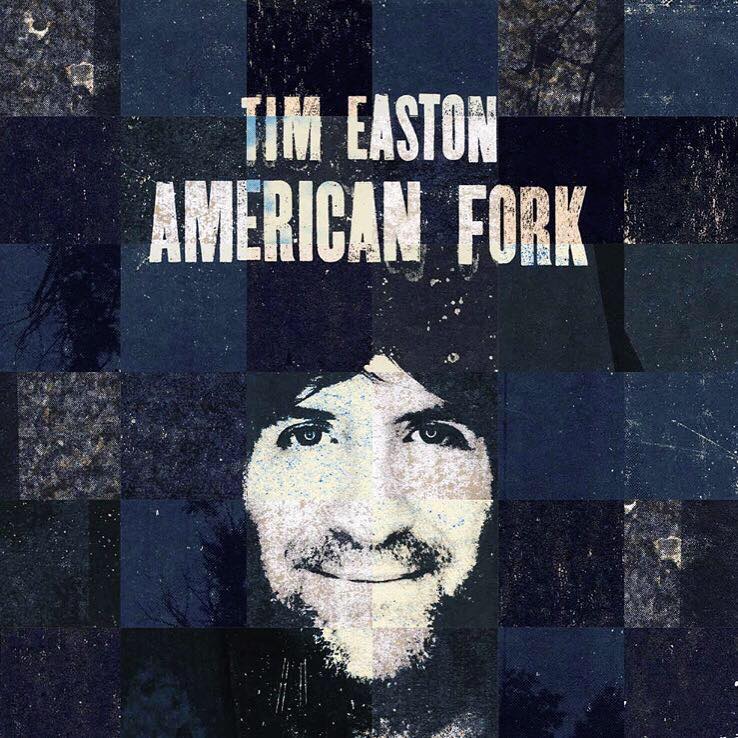

To American Aquarium's BJ Barham, Springsteen is also the greatest ever. Full stop. On his recent solo debut, Rockingham, Barham puts that admiration and influence on full display, working through an Americana song cycle about small-town living with a gruff voice and a simple message.

What is it, for you, that makes Springsteen so great?

Springsteen, for me — and I've argued this with plenty of people — he's simply the greatest American songwriter we've ever seen. [Bob] Dylan's good. I really like Dylan a lot. I really like Tom Petty a lot. Dylan wrote a lot of artsy, abstract stuff, too. Springsteen always writes to the core of America. Springsteen writes songs that 21-year-old hipsters in East Nashville can relate to or, you can play them for my father, and he relates to the same exact verbiage, same exact song. It's timeless. You play Thunder Road, you play Born to Run … you play anything from Born to Run and it could've happened today; it could've happened in the '60s.

There aren't many songwriters that we come across in this business that have that ability. And I'm one of the countless songwriters who spent my entire 20s at the “Church of Springsteen” and am, really, sometimes just doing a pale imitation. Everybody who writes songs about small-town living that comes out and says Springsteen didn't influence their music are liars. [Laughs]

He taught me that you can have a guitar and three chords and tell people stories about where you're from and people will relate to it. There's no greater lesson that I have learned than from Springsteen: Write what you know. He made New Jersey sound romantic. That's how good Bruce Springsteen is. New Jersey is a terrible place. Springsteen is the only guy who can make New Jersey sound appealing or romantic or nice or not a shithole. I can say this because my bass player and my guitar player are both from New Jersey.

Having never been to New Jersey, on my first tour, I made sure to book a gig in Asbury Park. On the way up, I was like, “Man, this is going to be a game-changer. This is going to be life-altering!” Then, you pull up to Asbury Park, New Jersey, and you're like, “What the hell?!” [Laughs] “Did they do nuclear testing here after the Springsteen records came out?! Maybe this is the desolate wasteland that came after the vibrant city he painted picture of …” Then you realize, that's how good Springsteen is. He's such a good writer, he can make New Jersey sound like a hotspot tourist destination.

Being a guy from a small town that's not really desirable in too many different ways, it taught me that you can sing about what you know — sing about things that are close to you — in a way that made it relatable to the rest of the world. On my new record, Rockingham, all of these songs are about my hometown. They are all about a very specific time and place. And I attempted to make these songs so that somebody in Anchorage, Alaska, or somebody in Wichita, Kansas, can hear these songs and put themselves in these characters' shoes. That's what Springsteen taught me, that most of us have the same perspective.

It's interesting what you said about how his old records are still just as relevant today. That's great for him — that he's able to write such timeless pieces. But it's also a little bit sad for us — that there's been very little progress.

Very much so. If Springsteen came around today, he wouldn't exist as Bruce Springsteen. He would've put out his first record, Greetings from Asbury Park, and he would've been dropped from his label immediately because he only sold 100,000 copies. And he might live in obscurity. If Springsteen came out today, he'd be one of the guys who're on the road 200 days a year playing in empty bars singing songs about common people. It was the right place, right time for Springsteen. Luckily, Columbia Records gave him three shots. That's unheard of today.

Well, he was a critical favorite, right out of the gate, some 43 years ago. But, you're right, the big sales didn't come along until later.

Don't get me wrong, by '84 or '85, that man was playing football stadiums — a level of fame, arguably, nobody today really understands … unless you're Beyoncé.

Right. A singer/songwriter doesn't do that.

Nobody walks into Giants Stadium and plays, at the root of it, folk music. Don't get me wrong: He had the bombastic band and, in the '80s, he made the horrible decision to add synthesizers to everything; but, at the base of everything, those are three-chord folk songs. Nebraska is a great example of what Springsteen sounds like in his room just playing an acoustic guitar.

I was just listening to Nebraska and Tom Joad. That's John Moreland. That's Jason Isbell. That's Lori McKenna. Those are the artists making that kind of music today. But, yeah, they are, at best, playing a nice theatre or maybe a small shed.

If you look at some of the outtakes from Nebraska … “Born in the U.S.A.” was supposed to be on Nebraska and there are acoustic versions floating around of demos he did for “Born in the U.S.A.” It's a haunting folk song about the reality of the Vietnam War and what it did to the American psyche. But, if you talk to anybody my age about “Born in the U.S.A.,” it's, “Oh, that's that cheesy Springsteen song.” It's all because of that synth line that makes it danceable and pop-py and sellable. But, when you strip everything away from any of his songs, they're John Moreland, they're Jason Isbell. They're everybody that we look up to today in the Americana scene. Springsteen just put 20 instruments over the top of it to sell it.

But he was a product of his environment. That's what was going on in New Jersey. If you wanted to play on the beach, you had to have a band that made people dance. He learned that, as long as he had the band to make people move, he can sell it mainstream. And he got to sneak in all these amazing poems. The best part about it was, America thought, “This is really catchy.” But they were listening to, in my opinion, the greatest American songwriter ever to write songs.

It's interesting because, I think, those are the people — much like Ronald Reagan trying to use it for a campaign song — they weren't listening. They're listening on the surface to the riff and the chorus, but they weren't actually tuning into it.

And it blows my mind because the first line of that song is such an epic line: “Born down in a dead man's town. The first kick I took was when I hit the ground.” WHAT?! [Laughs]

[Laughs] So do you have a favorite era or album? Or can you not pick?

For me, it's Born to Run. It's eight songs. It's perfect. A 47-minute record. It's funny that my debut is an eight-song, 45-minute record.

[Laughs] Hmmm. That is interesting.

[Laughs] Springsteen taught me that, nowadays, everybody wants to put out 16-song records with a five-song bonus disc, if you get the deluxe edition. Born to Run, arguably one of the best records that will ever be made, in my opinion … eight songs. It's the perfect four songs on each side of vinyl. I can't even get started. “Jungleland” … I still cry.

Every generation has great songwriters. For my generation, Isbell is that … for me. He's playing big theatres. Let's be generous and say he's playing for 3,000 people per theatre. That's one-tenth of what Springsteen was playing. We'll never see anything like what Springsteen was. It was a cultural phenomenon, the fact that America rallied around a songwriter. Beyoncé is lucky to sell out a football stadium now and she had 16 ghostwriters on every one of her songs. Springsteen was a guaranteed sell-out. So, if he booked a football stadium, he might have to book two or three nights because it sold out so quickly. I don't think we'll ever see that again, in our lifetime. It was such a perfect storm.

Looking back, I don't understand how it happened. It's like if John Moreland got famous, or someone you loved in your record collection that you wondered why nobody else knew about them got extraordinarily famous. The closest we have, to me, is Isbell. Knowing him pre-Southeastern and going to one of his shows now and seeing how big it is, it's still not even a speck on what Springsteen was, which is hard to wrap your head around.

For more songwriters admiring songwriters, read our Squared Roots interview with Lori McKenna.

Photo of BJ Barham by Joshua Black Wilkins. Photo of Bruce Springsteen courtesy of the artist.