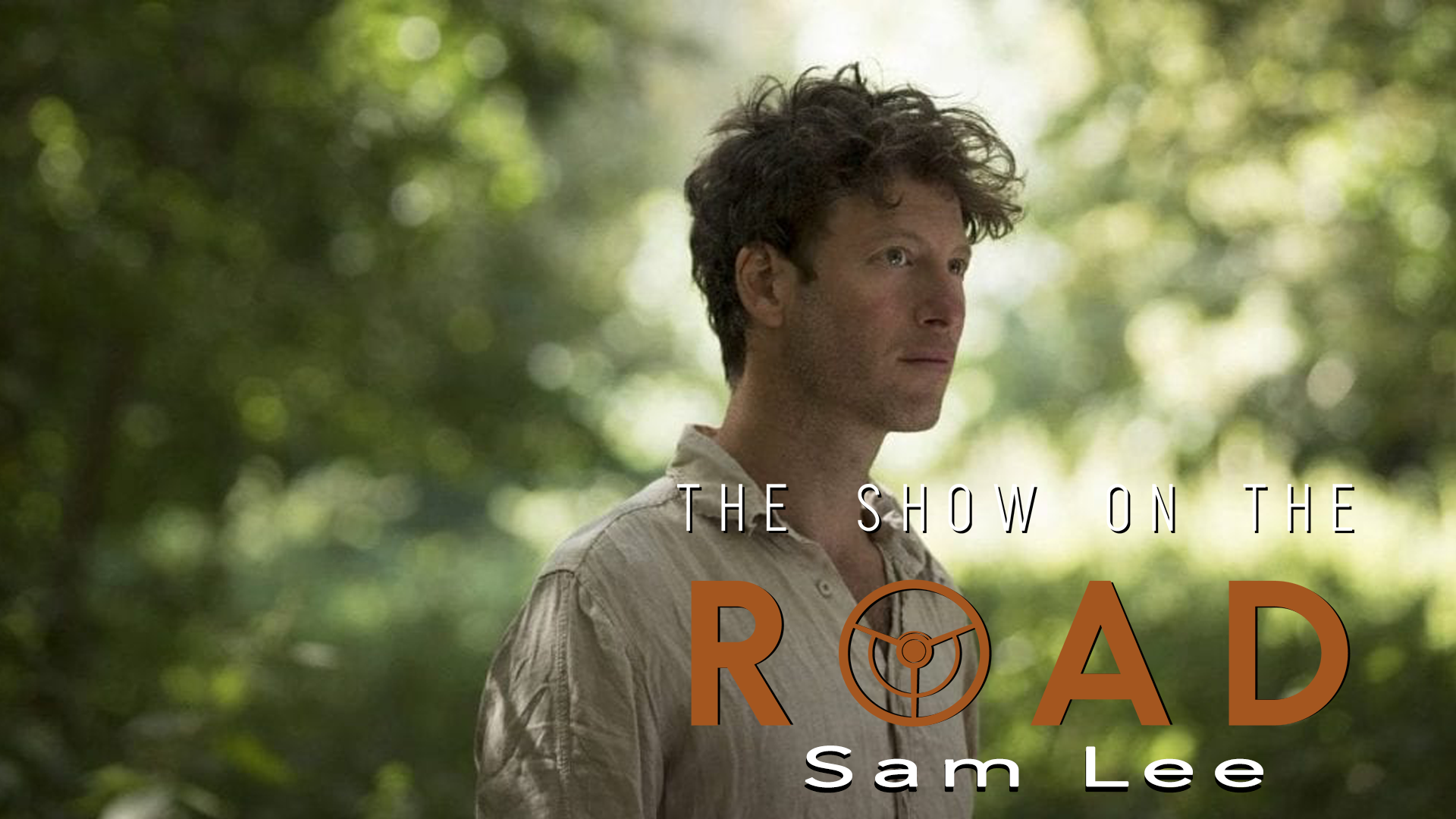

Sam Lee’s musical career grew out of his environmental activism, from the Mercury-winning album, Old Wow, to his ongoing conservation project Singing with Nightingales. The British folk star’s fourth album, songdreaming, released earlier this year, is his most creative venture yet. It’s a manifesto for reconnection with nature constructed from luscious, haunting reinterpretation of the songs of the UK’s Traveller communities.

Its title comes from the summer retreats Lee leads that bring people together to connect to their land and ancestry through song: “Singing to the land happens across the world in Indigenous communities that still have their relationship to nature very much intact,” says Lee. “It’s ceremony, it’s devotional work, it’s prayer.”

We spoke to Lee about songdreaming, how he sources material, queerness, connection to nature, and much more.

Sam, your music is usually based on traditional folk song, but these songs go far further from the source material than you’ve ever taken them before.

I had done a little bit of original writing on Old Wow, but this is an album where almost everything is written by me, some to the point where there’s no semblance of the primary folk song left. And that was a big risk, because I’m quite shy when it comes to thinking of myself as a songwriter. It’s not like I’m a seasoned Johnny Flynn or Anaïs Mitchell. It’s not my training, and I’m a very reluctant writer, because I failed English at school. I’ve always had a great sense of inadequacy.

What prompted you to step out of your comfort zone?

It actually came about in an unusual way – the songs were originally commissioned for a movie, The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry. It was an adaptation of a much-loved book about a man who walks the entire length of the UK, a portrait of our connection to the land and the healing power of passage-making. I was already a great fan of its director, Hettie Macdonald – her first movie, Beautiful Thing, was seminal for me when it came out in 1996 – so I was really excited to be involved.

We arranged and wrote lots of songs to capture the mood of the film and some were used, but there were all these, dare I say, leftovers? Being the resourceful, waste-not-want-not type, I said, “Well, these all have something in them that is powerful.”

What was your writing process?

I don’t have one particular method, but the way I work is a bit like the way I interact with nature. I’m a forager for sonic and lyrical opportunity, seeing relationships within words in the way that I see relationships within the ecosystem. You start to find what Simon Armitage, Britain’s beloved poet laureate, will call the “neon” moments, things that suddenly shine.

Can you give an example?

Absolutely. “McCrimmon,” the third song on the album, is a ballad I learned from my late mentor Stanley Robertson, who was a Scottish Traveller. There’s a lyric in the original which is, “no more, no more,” but I heard it as “in awe, in awe.” Suddenly a whole song about the state of awe appeared.

There’s another track which is a love song between a fair maid and a plowboy – I recalibrated and reframed it, so it’s a more complicated relationship between species that are in a state of separation. The folk songs say everything already. I’m like someone taking a Shakespeare play, resetting it, maybe adapting some of the language, like West Side Story from Romeo and Juliet.

Which of the songs came easiest?

“Green Mossy Banks,” which is actually about pilgrimage, was so easy to write. It was like, “Oh my god, I’ve been wanting to write this song forever.” And they didn’t even use it in the film!

What is it in that song that you had been longing to express?

The story of the film paints this wonderful portrait of free passage – there’s never a moment where it deals with trespass or permissions or this idea of private land. No barbed wire fences, or angry landowners going, “What do you think you’re doing here?” One could walk from Devon to the borders of Scotland and never have any issue.

But there is no person in England who goes on a country walk and isn’t affected by our punitive, archaic, and utterly unequal private ownership laws. That’s why I was a founder member of the Right to Roam movement. For all its avoidance of politics, “Green Mossy Banks” is a deeply political song. Social and ecological injustice is at the roots of so much of our international crisis.

Is the UK not quite a good place to walk compared to, say the US? The English have ancient rights of way that allow them to walk across private land, whereas try it in the US and you might get shot…

Absolutely. But where does the US get their notion of land rights from? They were inherited as an enhanced version of British law at a time when, in England, if you were caught poaching a hare or something, that’s it, you had your hands cut off, or you were hanged, or sent to Australia.

On the music video for “Green Mossy Banks” we see you surrounded by various mesmerising English landscapes.

It’s a combination of many of the pilgrimages that I’ve made with Chris Park, a druid, and Charlotte Pulver, an apothecary. At cardinal points of the year – the solstices, the equinoxes – we lead communal pilgrimages to places like Stonehenge, or the South Downs.

Are there any songs on the album that were inspired by specific places?

“Meeting is a Pleasant Place” is very much about the Dartmoor landscape, down to the very tor that we filmed the video on. The exact location shall remain nameless, because it’s one of the few tors that exist in a forest, as opposed to Dartmoor’s sheep-wrecked landscape of denuded grassland. It’s deep in beech and oak forests, which makes it especially stunning.

And the song itself came out of a Devon Gypsy folk tune.

Yes, and it contains this rather mystical language that had become something of a mantra to me. “Meeting is a Pleasant Place/ Between my love and I/ I’ll go down to Yonder’s Valley, it’s there I’ll sit and sing…” It’s bad English, but at the same time so powerful in its ambiguity. It could be a love song between two people, but in that Gypsy corruption of the words, suddenly it speaks about something so much bigger. So then I wrote my three verses as a love song to the land.

The appearance of the Trans Voices choir on the chorus turns it into something epic and anthemic…

It’s English folk gospel, as I call it. ILĀ, who runs Trans Voices, is an old friend and when the choir was set up I said I’ve got loads of songs that I’d like to speak to the queerness of land. Folk song often tends towards the heteronormative, and I want to break that down.

In the liner notes you also talk about the queerness of nature, what do you mean by that?

When you look at relationships within the natural world, sexual or otherwise, what you see is massive diversity in roles and identities. In the fungi world, for instance, there are hundreds and hundreds of genders, working collaboratively in community. Humans, too, need to start to recalibrate the way we behave in nature. So much of our subjugation and exploitation of nature has come through a male-dominated worldview and it’s not working.

One of the species you have a great connection with is the nightingale – as well as singing with them in secret woodland gigs every year, you recently wrote a book about their threatened extinction.

Yes, and when I’m with them, for seven weeks each spring, I get this sense of what is it like to be in a relationship that’s falling apart. That heartbreak, saying farewell, and knowing that it has a time limit to it. That’s what inspired the opening track, “Bushes and Briars.” It was the first folk song Ralph Vaughan Williams ever collected, and it’s a lament of a man and a woman who are separating. As somebody who spends a lot of time in bushes and briars trying to keep a relationship with a bird going extinct happening, that’s a space that is very familiar to me.

Coming from a background of singing acoustically, outdoors, how do you work up the big, dense sounds that populate your albums?

I do my writing with James Keay, who plays piano in the band. We both want a richness of sound, so that what are often very repetitive lines and melodies can take the listener on journeys through different emotional states. It’s about trying to paint as big a painting as possible.

As well as strings and horns and pipes, you’ve added a more pan-global feel with a Syrian Qanun, and a Swedish Nykelharpa.

We wanted to create textures that gave a sense of both the ancient and the unusual. I’d never used a Qanun in an arrangement before, though I have used dulcimers before on almost every album, which are part of the same family.

Maya Youssef, Britain’s best-known Qanun player, features on the one folk song that you haven’t changed, “Black Dog and Sheep Crook,” about a shepherd being thrown over by his lover because he’s “just” a shepherd.

I’ve kept its truth and entirety – it just felt so wonderful bringing the tragedy and the melancholy of the Qanun into that song.

So often in this album you’re grieving our detachment from and devaluing of the natural world. But the spirit and purpose of the music, as you describe it, is also to re-establish those connections. What are your current priorities for climate activism?

At the moment, there’s a big campaign to get young people voting, and voting for nature, in the UK. Hope for me is always about having a plan. And there are many brilliant plans out there. It’s about overcoming apathy and resistance and reawakening people to what we have to lose.

I can’t speak to what I think the outcomes will be, I think that’s a dangerous thing to do. But I hope that the album has as many opportunities to instill hope and beauty as there are moments of doom and tragedy.

Photo courtesy of the artist.