Music is full of innovators, some worthy of the word, some less so. Jazz pioneer Joe Sample certainly fits the former. Coming out of Houston, Texas, Sample's artistic roots ran deep and wide. And he wasn't afraid to let them reach into everything he did, blending blues, soul, gospel, and other forms into one. Sample started playing piano at the age of 5 and passed away, in 2014, at 75. In between, his main band project was the Crusaders, a jazz group based in Los Angeles, California, with which he crafted a lasting legacy before they (mostly) disbanded in 1987, despite a few reunion projects.

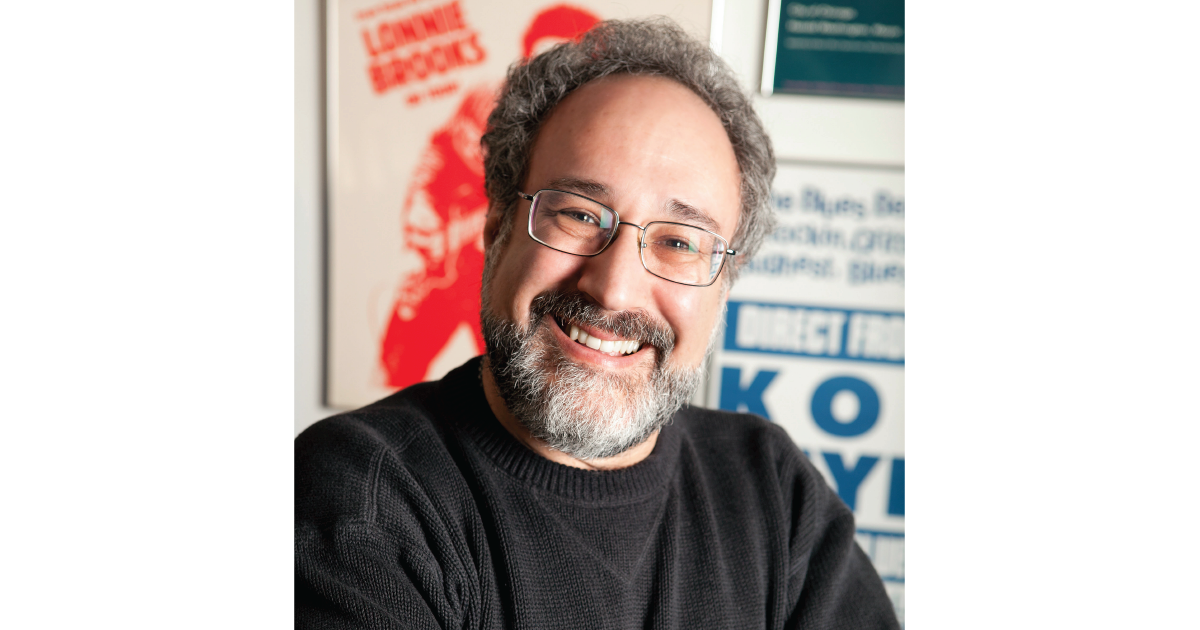

Jonatha Brooke, likewise, is an innovator within the folk-pop world that she has inhabited since her debut as half of the Story in 1991. Her literary lyrics and sophisticated harmonies somehow manage to both anchor and buoy the songs on the eight solo records she has released, including 2016's Midnight. Hallelujah. And then there are her deeply heartfelt musical theatre projects — one of which, Quadroon, was in development with Sample at the time of his death.

It makes sense to me why you'd pick Joe Sample because he's somebody who softens the complexity of jazz with the soulfulness of rootsier genres. From that perspective, I can totally hear his influence echoing through your work. Did I get that right?

Yeah. Yeah. I think that he, himself, would have said, in some ways, he had a real pop ear for melody. He was not trying to be complex or intellectual. He was just trying to write a great freaking melody. He just wanted to write a great song. He was passionate about it making a lot of sense. It's gotta feel like a complete idea: You state your theme and you have to make it musically make sense. It has to tell a story. There has to be an arc. He's a great storyteller, musically.

I get that. But, at least to my ear, jazz can't help but be a little bit complex. It's not just G-C-D — a three chords and the truth kind of thing.

No. It's so amazing how he voices his chords. They are richer than anything you've ever heard before. But it's deceptive with him. Some of his songs are absolutely simple, just three or four chords, but they're so rich in their embellishments and their harmonics, it gives you that extra bolt. Songs like “One Day I'll Fly Away,” “Street Life,” “When Your Life Was Low” … those are just beautiful, beautiful, classic, singable pop songs.

Again, I'm an absolute dummy about jazz, but I read up to learn that he and the Crusaders played hard bop, which is the bluesier cousin to bebop. School me on that.

[Laughs] Well, I'm gonna sound like an idiot …

Better you than me! [Laughs]

When Joe would tell stories about it … Full disclosure: My husband managed Joe for 35 years, so I got to get an earful, which was an amazing history of jazz and music. But he would always say that all the hard cats were in New York and the Crusaders were like, “Fuck this shit. Where's the melody? We're going to L.A.” [Laughs] And they did what they did, which was more melodic and less lanky, less intellectual and trying to impress people. They had soul. They wanted to keep that element in their approach to jazz.

There was a quote of his included in his New York Times obituary. It's perfect: “The jazz people hate the blues, the blues people hate rock, and the rock people hate jazz. But how can anyone hate music? We tend to not hate any form of music, so we blend it all together. And consequently, we’re always finding ourselves in big trouble with everybody.”

[Laughs] That's awesome! He used to tell this story on stage about this one Crusaders song, “Way Back Home.” Really simple song. Gorgeous, though. Simple, but make-you-cry beautiful. At one point, I guess it was on some kind of tape that the Symbionese Liberation Army was using for their brain-washing. So there were these pictures of Patty Hearst and this song in the background, so the FBI came after the Crusaders because they wanted to know what connection they had to Patty Hearst and the Symbionese Liberation Army. [Laughs] Then they would play the song and it's almost like a hymn, really. The irony was just crazy.

[Laughs] That's hilarious. So they would get in trouble even when they had nothing to do with anything!

Exactly! [Laughs] They just got in trouble.

Too funny. So he started out on acoustic piano, but later gravitated toward electric keyboards. That must've opened up a whole, huge world of creativity for him.

I think so. And the way he played those instruments is absolutely iconic — the way he played the Rhodes and the Wurli. He has one of the most sampled catalogs in the world. The irony is that his name is Sample. I don't know anyone whose riffs and grooves have been more sampled than Joe's. It's those groovy Crusaders Wurli and Rhodes parts that are central to that vibe he would create, that rhythm-and-groove vibe that people are still craving.

Then, as session guy, he played with Joni Mitchell, Marvin Gaye, Miles Davis, Tina Turner, B. B. King, Minnie Riperton, Eric Clapton, and …

Chaka Khan!

Chaka-Chaka-Chaka-Chaka Khan. Yeah. Then he was working with his Creole Joe Band playing zydeco at the end. What sort of skill does it take to be that versatile?

Oh my God. Ridiculous, super-human skills. You have to have that good of an ear that you're always absorbing and still making it your own and turning it into a signature sound. He had all of that. He had the technical skills. He could just blow. But, also, he was always really working on the composition. That was his first-and-foremost love: “How can I make this a beautiful composition? Where should it go? What story am I telling?”

And there's not a single artist that I saw listed that isn't overflowing with soul, themselves, no matter what genre they're in. So, if they're calling on him, there has to be a kindred spirit there.

Yeah. And he would bring so much to the table. I'm surprised … well, I'm not surprised at all … but, often, I would imagine, he should've been a co-writer on many of those sessions because he was bringing it — bringing the groove, bringing the riff that created the song. But those were the days when session cats were just session cats.

Speaking of co-writers … perfect segue … Quadroon. Talk to me about that.

[Laughs] That's a really cool project. It's just devastating that he's not here to finish it. It's a beautiful, large, passionate story. It was his idea to write about this nun who lived in New Orleans in the 1830s. Her name was Henriette Delille and, in real life, she's in line for canonization at the Vatican. She was Creole, so she could pass for white. And, at that time, if you were in that category, you could become a quadroon — you could marry a wealthy, white merchant. Her mother was married to a French merchant. She was his second wife. She was the kept mistress wife of this very wealthy merchant. In some ways, in that time, it was a better option than trying to make it on your own.

Henriette's mom wanted her to go into this line of life called plaçage, but Henriette wanted to be a nun. She wanted to serve God. That was all she wanted, ever, from the time she was small. So, she bucked the system and ended up befriending this French priest. This is all true. And this French priest helped her with her ministry, got her recognized as a nun by the Vatican before she died. She ended up starting an orphanage. She had her own ministries. And she had these schools for poor Black kids and Joe ended up going to the schools that her sisters and followers still run in the Houston area — New Orleans and Houston.

Joe grew up hearing stories about Henriette Delille his whole life and, after he moved back to Houston a few years ago, he decided to research the story and talk to the nuns who were still in New Orleans. They gave him their blessing to write something about this amazing woman. So that's what we've been working on. It's called Quadroon. I think we wrote 20 songs before he passed away and we were able to do a small reading in Houston at the Ensemble Theatre before he died.

That's great. So you're gonna keep pushing forward?

I'm gonna keep pushing. I'm pushing on.

Since you did get to spend a good bit of time with him, what's either the lesson that's stayed with you or the impression of him that lingers for you. Linger … you see what I just did there?

HA! I see what you did there! [Laughs] I think it's that he never tired of creating music. He was really prolific. He always had a new idea. And he wasn't afraid of sucking. [Laughs] He didn't edit himself before it was time. He just let ideas flow. I'm left with memo recorders of hundreds of snippets of ideas that I can still work with. But he just kept writing stuff. That's my biggest inspiration. He was tireless. And he never repeated himself, too. His last record is called Children of the Sun with the NDR Bigband orchestra. It's a masterpiece. It should be an Alvin Ailey ballet. And then the Creole Joe band. And the musical. He was just incredible and I take such inspiration from him because he was 75 and still pumping out ideas!

Photos courtesy of the artists.