Tag: folk-rock

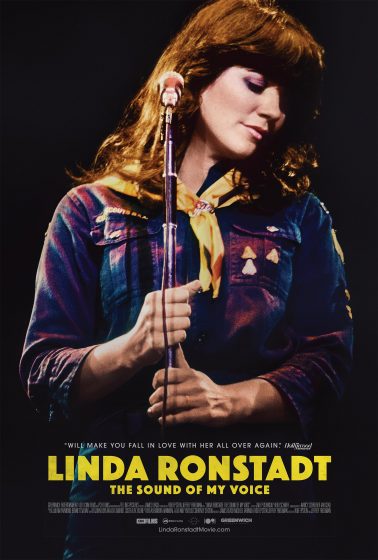

Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass (Part 2 of 2)

In honor of the new documentary film, Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice, and in appreciation of her connection to bluegrass — and in an attempt to shout it from the proverbial rooftops! — we’re reprinting Dan Mazer’s 1996 Bluegrass Unlimited interview with Ronstadt split into two parts, but in its entirety on BGS. Special thanks to the team at Bluegrass Unlimited for partnering with BGS to spotlight how bluegrass has touched one of the most important and truly iconic voices to ever grace this planet.

(Read part one of “Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass” here.)

“Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass”

By Dan Mazer. Bluegrass Unlimited, June 1996

…Our conversation moved to a discussion of Alison Krauss’ musicianship. Krauss seems to have an incredible variety of influences, which come out when she wants them to. “And in an appropriate manner,” Ronstadt continued. “There seems to be a general agreement among all the people that I know – whose various subjectivities are very strict and very demanding – that Alison has the best taste of any of those people.

“Every fiddle player that I’ve ever worked with will be tempted to play sound(s) like donkeys braying; or just play too much – play ‘flash’ licks in an inappropriate manner. (I call it) ‘The Paganini Syndrome.’ And Alison never is.

“Her pitch is completely stunning! I’m a pitch nazi, and she’s even a little more strict than I am, in terms of pitch. And the thing that I like the very best about her playing is her rhythm. She’s got that great, easy, loping sense of the groove that bluegrass players generally don’t have. When it’s right, of course, it’s got a great swing to it. But bluegrass players have a tendency to get a little stiff and a little on top of the groove. And she never does! I don’t think she’s played with drummers that much, but we put her together with Jim Keltner, and it was just an amazing thing. She’s got the same sense of the groove that he does, and he has the effortless pocket. I consider her as good as any musician I’ve ever worked with. My cousin (David Lindley) said she was his favorite fiddle player ever. And I love her. And also, she owns Maria Callas’ bed! (Laughter) I don’t know why, or how she managed to get her hands on it, but she did. I was jealous. I wanted to be the one to get it. Emmylou Harris and I are both Maria Callas fans. Slobbering, drooling Maria Callas fans!”

When asked to comment on other bluegrass acts, Ronstadt confessed that she doesn’t listen to any modern music of any style. In fact, she was unfamiliar with many of the major country acts. Nor had she ever heard of the IBMA. “Honestly, the only ones I know (are) Ricky Skaggs, Alison, and (the) Seldom Scene,” she said. “But before that, it really was those original guys (Flatt and Scruggs and Monroe). I mean, it was such a short-lived era. And before that, the Blue Sky Boys, which wasn’t really bluegrass, but which really sorta fed right into it. I love those guys, and I listen to the Louvin Brothers a lot. So I listen to all the stuff that led right up to it.

“I know very little of any kind of contemporary music. I just don’t. I listen to NPR, and I listen to Maria Callas and them, and I listen to a lot of Mexican music, and that’s about it. And if it penetrates through that it’s usually because Emmy calls me up, or John Starling calls me up, or Quint Davis. Quint Davis is the guy that runs the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, and he put on that thing on the Mall for the inauguration. That’s where I saw Alison. I was just blown away by her!

“I don’t know modern stuff. I haven’t a clue. It seems like when we did the ‘Trio’ record, nobody was interested in traditional music. And then that record was pretty successful, and at that point, Ricky Skaggs was extremely successful, but all of a sudden, I don’t know. I don’t watch this type of stuff on television. I haven’t got the vaguest idea, and I don’t listen to the radio. I have a great respect for anything that anybody does. I mean, I think it’s just so hard to make a record – any record – that I don’t like to put myself in the position of, ‘This is good, and that’s not good,’ like a bean-counter. But I have to say that (modern country fails) to capture my interest.

“There’s always music in front of my face. If I was gonna sit and listen to Mozart, (and) someone said, ‘OK, this is gonna be it (you can only listen to Mozart) forever,’ I’d go, ‘OK.’ And if someone was playing me some Mexican traditional music, and they said, ‘This is gonna be it forever,’ I’d go, ‘OK.’ Because there’s enough in any of those things, to (keep me interested).

“Somebody came over to my house the other day with some musicians from Madagascar. They sit down in my kitchen and played this Malagassi music, and it just blew me through the wall! So, if they had said at that point, ‘Well, you’re gonna have to sing a little Malagassi now,’ I would’ve said, ‘Well, OK. Fine!’ I could’ve got right down and sung with them, and had no problem at all. But I can only concentrate on one thing at a time, and if that thin is interesting, I just don’t have any particular need to shift my attention.

“When John Starling comes out to visit me, he sits down at my kitchen table with his guitar, and we start singing. I get pried back to English. But I’d really rather sing in Spanish or Italian. Because all that stuff (bluegrass and country) is based on rural southern pronunciation. And in Spanish – if I’m singing a Latin jazz thing that’s a Caribbean base, I have to push myself from my northern Mexican rural accent into a Caribbean accent, which is painful for me. I find it an unpleasant way to pronounce the language, but I have to do it in order to get the rhythms right. So I do it. I really push myself into that other accent. But I prefer singing in my own accent – the accent of my family’s region. I can just get so much more sound out of my voice in that language.”

Over the course of a career, an artist makes many decisions based upon the age-old dilemma of commercialism versus artistic merit. What the public wants to buy is not always what the artists likes [sic] to paint, play, or sing. Ms. Ronstadt has lately recorded opera, Big Band and Mexican music, none of which usually sells platinum in today’s market. It seems that she has reached a point in which she doesn’t have to worry about selling a certain number of records; her musical decisions are now totally artistic. “Well, they were to start with, too. It’s just that I wasn’t as good at executing them!” She protested with a laugh. “And I find that now. I’m making my choices based on an artistic thing, but I am also finding that my choices were made for me when I was a baby. It’s getting harder, though. I do find that the record companies have a tendency to stick their oar in a lot more now. It’s very nervous-making. Although, the one person that I’ve allowed to submit material and give advice – I don’t always take it, but I always consider it – is (Asylum Records President) Kyle Lehning. He’s an amazing guy! He really, genuinely likes music, first of all, which is rare for a record person. Second of all, he’s extremely knowledgeable, and he has great taste in songs. And he seems dedicated to the idea of trying to save what he can that’s quality, and nurture it.

“(The latest project) started with several nagging phone calls from John Starling!” She laughed. “John Starling doesn’t get down behind traditional Mexican music! And then Emmy calling me, because Emmy and I are such fans of the McGarrigle Sisters. We were talking about doing some television stuff. We were just trying to think of how we could get in the living room together again with John Starling. So we started working on tunes, like the Carter Family songs that only Emmy and I would be interested in. And maybe John Starling or Claire Lynch, or somebody. John had, a long time ago, sent us Claire Lynch records, saying, ‘You really gotta sing with this girl. She’s real wonderful.’ So claire and Emmy and I have done some stuff together.

“And then, I’ve been working with Valerie Carter. She put a record out in the ‘70s. Everybody in Hollywood was after her. She’s an extraordinary singer, and she was exceptionally beautiful. She was about 19, I think, then. Lowell George and Mick Jagger and Jackson Browne and J.D. Souther and Danny Kortchmar – everybody wanted to work with her. Everybody tried to, and then George Massenberg, who is my production partner – who I met through John Starling – did produce a record from her, and so did Lowell George. I sang on it. Then she just had some problems, and she dropped out of sight for about 15 years, which was really a tragedy for us. ‘Cause she’s one of those girls that can sing as well as Whitney Houston. She’s got that kind of chops. But it doesn’t sound like her. It’s a very distinctive voice. But that kind of ability. It was too bad, ‘cause she was (a) really interesting singer. So she’s now been singing on the road with James Taylor a lot. I used her to sing a lot on my last record, that I put out. The blend between her and me and Emmy was just really magical! So we’ve done some stuff together, the three of us.

“But what Emmy and I wanted to do was just explore. See what we could go find out there. We wanted to push the limits a little bit, and see what we could find in terms of texture, combining styles, of things that we liked that don’t always fit in one little (category). Like the McGarrigle Sisters. Where do you put that? It’s not really traditional folk music, and it’s got traditional roots. It certainly isn’t bluegrass. And the sentiment is too unbridled for current pop, ‘cool’ standards. But it’s very intelligent music.

“There’s other stuff that is kind of like that; that’s kind of ‘out there.’ And there’s some stuff that’s just real, real traditional. So we’ve just been fooling around with various singers. And then I sang with Claire Lynch and my cousin John, who’s got a wonderful voice – on two songs.”

Although she maintains that after a project is finished she doesn’t care what happens, Ronstadt is intensely involved in its creation. “Oh, I mix everything! I do every single thing,” she declared. “I make the record, I do the arrangements, I do the harmony arrangements, I do a lot of the instrumental arrangements. Nothing is done on the record without me being there. But when it’s finished, I never listen to it again. You can take it and throw it off a cliff, for all I care. I’ve heard it and I’ve done it, and that’s the experience; and now I go on to something else. So at that point, I surrender it to the record company, and they do whatever. They can shoot it with a gun if they want to. I don’t care what they do. Long as they don’t shoot me.”

Returning to the topic of bluegrass, Ronstadt commented, “I understand what [the banjo] does, rhythmically. And I appreciate what it does – that syncopated thing; the difference in all those accents.

“I think of the banjo kinda like I think of the trumpet in mariachi, which is: trumpet was brought in about the same time that the resonator was added onto the back of the banjo. It was a ‘radio’ event, and a good one. It was a really good thing; it needed that high end to cut through. But if somebody came to bed and blew a trumpet in my ear, I’d get annoyed! If somebody came to bed with me and started plucking a banjo, I would probably jump right up to the ceiling! But it’s a great instrument in the orchestral blend. It’s really got a great place. And I don’t think the banjo will ever go out of style.

“Those other instruments are a lot more flexible. They can bear a lot more. I’ve really become a complete mandolin fan, ‘cause I’ve been working with David Grisman. I just think he’s a genius. I knew his playing. I knew he was considered a ‘hot chops’ player. I think he plays bluegrass sometimes, but he really predates and transcends all of that stuff completely. I mean, he can play like a classical player. I’ve never heard anybody with dynamics like that, and I’ve never played with anybody that could play with a vocalist; and play little internal harmonies. He just flits around like a little hummingbird – all around the vocal line – and plays a beautiful little harmony for a while, and then he goes off to a rhythm pattern, then he comes back. He has great ideas for voicings, and he has very, very good rhythm ideas. I just love to work with him. I think he’s brilliant.

“You know what I think is missing from bluegrass at this point? And from all that kind of traditional music? Dancing. That’s what I discovered with Mexican music, was that it is dance music. Period. I think, as is fiddle (music). As soon as you uncouple it from (dancing), the music changes. It’s the same way with pop music. As soon as it became recorded music – people started dancing in discos to recorded music – the music stopped being alive, and it stopped changing in a real vital way. Started changing in a more static, strange, mechanized way.

“So my suggestion, to the bluegrass world would be, one should never uncouple that music from dancing. There should always be dancers involved with bluegrass music.”

The author commented that singing is also something that’s been taken away from most people and given only to professionals. “Yeah, it’s an outrage! In Mexican culture, everyone sings,” she responded. “Everyone knows all the words, and they all sing. We sing at the dinner table. Whatever you’re doing, you sing. You sing in a funeral, you sing at a birthday, you sing at a wedding. You sing if you’re happy, you sing if you’re sad. It’s a thing you get to do to help you along with your life. Everyone should sing. It’s a biological necessity. Even little babies sing. I mean, even when they’re pre-verbal, you hear them kind of leaning into a sound.”

(Read part one of “Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass” here.)

Photos and artwork courtesy of Shore Fire Media

Article appears courtesy of Bluegrass Unlimited

STREAM: Kacy & Clayton, ‘Carrying On’

Artist: Kacy & Clayton

Hometown: Wood Mountain, Saskatchewan

Album: Carrying On (produced by Jeff Tweedy and recorded by Tom Schick.)

Release Date: October 4, 2019

Label: New West Records

In Their Words: “Jeff and Tom have taught us a lasting lesson on what’s important and not important when making music. I can recall moments when their suggestions caused me to feel panicky and vulnerable, but I can see now that they were encouraging us to let go of unnecessary fixations. And those moments have all ended up being my favourite parts of the two records we’ve made with them. It’s easy to cling to your own ideas out of insecurity but trusting someone else’s judgment can allow you to be very free.” — Clayton Linthicum

“Making this record felt purposeful. The songs came together nicely and we integrated them into our live set with Mike Silverman and Andy Beisel leading up to recording. Returning at The Loft in Chicago seemed like, ‘Hey guys! We’re back again and we’ve been practicing so let’s make a better record now.’ It was three or four days and the whole thing was tracked and marked with a B. Working with Jeff Tweedy has been a mystical and Midwestern experience for Clayton, Mike, Andy and I. He shies away from seeming authoritative and that style of leadership has strongly resonated with us.” — Kacy Anderson

Photo credit: Mat Dunlap

The Show On The Road – The Lone Bellow

This week, Z. Lupetin speaks to the founding trio of one the most respected and sought after folk-rock bands in the country, The Lone Bellow.

LISTEN: APPLE PODCASTS • MP3

Their hedonistically heavenly harmonies have lifted them from playing tiny bars around their founding home base of Brooklyn, New York to adoring audiences at venerable venues like Red Rocks Amphitheatre, the Apollo, and The Ryman Auditorium, in their new home of Nashville, Tennessee. The Lone Bellow have a rapport that is intimate, hilarious, and — when it calls for it — deadly serious. The band is full of so much heart and genuine insight that you can’t help but lean in and listen.

The Rails Meld Folk Roots, Rock ‘n’ Roll Cred

Couples don’t get more folk-rock than The Rails. On one side of the hyphen you have Kami Thompson, whose parents are Richard and Linda, one of the most famous couples on the British folk scene in the 1970s. On the other, you have James Walbourne, who has been guitarist to rock ‘n’ rollers from Jerry Lee Lewis to Shane McGowan to Chrissie Hynde. They have been playing together ever since first becoming an item, and the now-married couple brought out their first album, Fair Warning, in 2014. Now Cancel the Sun, their new record, is showing their fans exactly who they are.

BGS: Your latest album couldn’t be more different from your first. That one was stripped back, bare, traditional — this one’s absolutely rocking out! What’s behind the evolution in your sound?

Kami Thompson: With Fair Warning we set out to make a folk record within certain parameters, because we really liked the ‘70s folk sound. We were writing to that, and using traditional songs…

James Walbourne: My rock ’n’ roll background and Kami’s folk backgrounds have melded together on this one. All our influences came together and this time we weren’t trying to be anything — it was just a true representation of what we are.

Kami: I think of it as us at our noisy best, playing the music we like to listen to.

So what kind of music do you listen to together?

Kami: Well, we don’t listen together. We’ve got quite different tastes. But we both grew up with the same music around us as teenagers, that inescapable ‘90s alt rock and Americana and Britpop. I listen to mainstream pop — PJ Harvey and Elliott Smith were my faves growing up. James is more the tastemakers’ tastemaker…

James: I don’t know why she keeps saying that! I was just a music fanatic really.

Kami: His dad took him to see Link Wray when he was, like, 8.

James: He’d take me to see everyone from Frank Sinatra to Johnny Cash and Miles Davis and Jerry Lee Lewis. That was the biggest influence for me, and his huge record collection. My big hero was Elvis and that’s who I wanted to be. Who doesn’t? So I never thought about doing anything else but be a musician. And now I’m screwed because I can’t…

Kami, your biological parents are Richard and Linda Thompson – were you always destined to express yourself musically?

Kami: My father left my mother when she was pregnant with me, and they didn’t speak to each other until I was much older. So I was raised by my mum and a fantastic stepfather and our house was actually music-free. I would go to festivals with my father when I saw him on holidays and on the odd weekend. That was where I experienced live music, but it was the ‘80s and folk was so uncool to me then. My stepfather is an old-school Hollywood agent from Beverly Hills who used to represent Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif and Richard Harris, so as a kid I went to film sets and I thought that was the coolest part of show business.

Talking of cool… James, you’ve played with Jerry Lee Lewis, The Pogues, and you’re currently Chrissie Hynde’s lead guitarist in the Pretenders. Which of those gigs has been the wildest ride?

They were all wild in their different ways. The Pogues was probably the wildest because you never knew what was going to happen, ever. But I feel very lucky to have been able to play with all these legends.

And the pair of you owe a debt to novelist and music critic Nick Hornby, for introducing you…

Kami: We have to make sure we send him our records whenever one comes out as due deference!

Did you feel any nervousness about making music together?

Kami: Not really. When we were in the early days of going out we’d drink too much and get our guitars out and noodle. It just seemed an obvious thing to do. We were both looking for a creative partner as well as a romantic partner so those two fell into place simultaneously really well.

James, you previously had a band with your brother – who’s it easier working with, a brother or a wife?

That’s a good question! My brother lives in Connecticut but he’s visiting the UK right now so I’ve got to be careful… but it’s pretty similar. You learn what to say and what to leave out. When to shut your mouth, really. Being in a touring band is like that – it can be hard to not fight. We’ve come up with a solution for now, we have to separate the work from the relationship to a point. Otherwise it takes over. We did that with the songwriting as well… we had to figure out a way to make it work, we weren’t very good at it before.

Kami: The last record we made we weren’t getting on professionally and relationships were frayed. We had to find a different way to work this time and we thought and talked about it a lot. James quit drinking a year and a half ago which has had an incredibly beneficial effect on how we get on. We found a way of writing lyrics and tunes independently from each other, then hashing out what we had in properly delineated office hours.

Are you ever tempted to take holidays alone?

Kami: Oh god yes! We’re both difficult to live with, if we take a big step back and a truth pill. We have to work at finding time apart the way other couples have to put work into spend time together.

James: She just went to New Orleans only this year! And I’ve been away with the Pretenders a hell of a lot in the last three years, a couple of months at a time.

What about the mood of this album? There’s a common theme to a lot of your writing, a world weariness, a pessimism…

Kami: Yeah, we’re a right laugh to go to the pub with! James is more of a storyteller, more of a narrative writer, but I can have a dark view of things. It’s not my only view but my positive thoughts don’t always make for good music, it’s so hard to write a cheerful song that doesn’t sound trite. It’s easier to be grumpy.

James: The same things irritate us, I think. We have a kinship over the world’s irritating stuff! But our singing together, too, is telepathic now. We don’t even have to think about it, which makes things a lot easier.

And which of the songs on the album are you current favourites?

Kami: I love “Cancel the Sun” because it’s that tip towards the psychedelic rock and James’s wigged-out guitar solo at the end makes me really happy.

James: I think it hints towards a different direction, a bit chamber pop Beatles. It points to more possibilities down the road. The other song I really like is “Ball and Chain” because it was one that came straight down from the heavens. It was very quick to write and to finish, and that’s always a good feeling.

Photo credit: Jill Furmanovsky

Dalton Domino Emerges Intact from His Exile

Dalton Domino had pretty much ticked off everybody he knew, prompting one friend to remark, “Looks like you’ve been exiled.” That off-the-cuff comment inspired the title of Texas musician’s rugged new album, Songs from the Exile, which he wrote in a year fueled by anger, addiction, and a desire to figure out exactly why he was making so many bad decisions.

“I have a really good knack of shooting myself in the foot, talking shit when I shouldn’t talk shit. It’s one of my biggest character flaws that I have,” he admits. “I’ve driven off a lot of people because I think that I’m right sometimes. And what that does, some people just stopped answering the phone.”

Disconnected from all but a few friends and striving to sort out his worst demons, Domino resurfaced with the autobiographical material that comprises Songs from the Exile. Surrounded by highly-regarded roots musicians chosen by producer Justin Pollard, Domino placed these hard-won songs against a live, in-the-room arrangement, which stands in stark contrast to the orchestration of his prior album, Corners. Not long after wrapping the sessions at Dauphin Street Sound in Mobile, Alabama, Domino checked himself into rehab — again.

More than once, his sobriety has helped him reconnect with his family, whose strong presence is felt throughout Songs from the Exile, particularly on tracks like “Half Blood” and “Hush Puppy.” His grandmother even kept him company as he drove from Dallas, where he lives, to Memphis, where she stopped off to see her son. Domino then detoured to Huntsville, Alabama, to catch up with his dad before swinging through Nashville for a gig and a chat with BGS.

BGS: There was a whole lot that happened leading up to this record, it sounds like.

DD: It was, man. It was a lot of falling off. I was sober for a little while and hitting meetings, and I just got in this rut. I don’t know what happened. I wasn’t paying attention and started drinking again. I thought I was fine and started drinking a little bit, and started doing some other stuff. It just started snowballing.

I cut this record and I was really confused and I had a lot of questions. And it was knee-deep in self-medication with questions. There were moments of clarity and then moments of, “What the fuck is going on?” I don’t know, it was like a quarter-life crisis. But yeah, it was a weird spot. That week getting away [to Mobile], it was nice to do that. It was nice to clear my head a little bit.

So you were using these songs to sort out what was going on with you?

Yeah, man. I was just angry at stuff. In hindsight, I thought I knew what I was angry about. In the same breath, in hindsight now, the stuff I was mad about wasn’t stuff you should be mad about.

It seemed like there was a breakup that threw you way off.

There was a breakup, then it was like, “Well, looking back in my life, they always leave this way. So what did I do?” And then it led to, “It’s me. I was the problem.” I was the asshole in the situation. Not them. I always place blame on them, then that led to, “Well, why do I act this way?” And then that looped into all these other questions I had about myself. That’s where a lot of the songs came from.

“Half Blood” seems like it was ripped from a page of your life. Is that pretty much how it went, where you were in the driveway going, “This is my fault that this is all falling apart”?

I think that every child of divorce at some point thinks that the reason that their family split up is because of them. I think it’s because that always happens with everybody. But that specific story, I set out wanting to write a song about my sister. We have different moms, that’s my half-blood sister. But I took it into a friend of mine, and she was tinkering around with the idea. She goes, “You know, you guys don’t really have too much to complain about, because your family does love you despite their flaws.”

These songs are very introspective, but it seems like you wrote them with an audience in mind, or at least produced them that way.

Yeah. That’s Pollard. I was trying to work on melody a little bit more, in the actual writing process of it. I know I needed to work on melody a little bit more. So, going into sitting down and writing the songs, I knew that I wanted them to be more melodic. I think that you can say whatever you want to say and you can put a good melody on it. At least for me, whenever I sit down to write a song it’s always to share with other people. It’s never just like, “This is mine. I wrote this for me to get off my chest.”

I wanted to ask about “Hush Puppy.” Is that based on something you overheard as a songwriter?

That’s a true story. That’s about my grandfather. He had this hush puppy recipe and he would never let anybody in the kitchen while he cooked it. And we thought he was always going to be around forever. We never did think to have it. But I made sure after writing that song, I sat down and got my grandmother’s cornbread recipe because I don’t want that want that to go the way of the buffalo. But, yeah, it’s a true story. It’s about how he died. He died alone in a V.A. hospital in Memphis.

What was the response when you played that song for your family?

My grandma liked it. You know, they all liked it. Yeah, they thought it was funny. I always tell a story about him. He was a character of his own, man. He was funny. I wish he was still around. He would enjoy all of this because he loved country music. He would enjoy coming up to Nashville and seeing stuff about Johnny Cash and Hank Williams. When he was alive, I wasn’t into country music. I just kind of ignored it. I loved punk music and I still love it, really hard stuff. My grandfather would love all this.

What was it like to see your dad again?

Dude, it was awesome, man. I hadn’t seen him in about a year and a half, or two years, and it was cool seeing him again. We talk on the phone and stuff but I hadn’t seen him in person in forever. He still is the same. I’ve got to drive back to go sign papers because I bought a car. He’s a car salesman. I asked him about a certain car and he was like, “Well, let me show you one. Why don’t we just go ahead and put you in this one?” And, “You know you’re qualified for a trade-in right?” I was like, “Goddamn it.” He said, “Go to your show, I’ll have the paperwork ready.” So I got to go back down there.

He made a sale.

Yeah, he made a sale, man! He’s the finance guy though. But, man, it’s always good seeing him. I saw my little brother last night, but I’m flying him out for a big show out in Lubbock on the 31st. So he’s going to come out there. The show’s 18 and up, and he just turned 18. So I’m going to show him Lubbock. Lubbock is my stomping grounds. That’s the place where I picked out to move to, so I consider Lubbock home. It’s his first time out there, and his first time at one of our shows.

I’ve not been to Lubbock.

Goddamn, it’s a blast!

So for those who read about what you went through, and they’re curious about how you’re doing now, what would you say about your frame of mind and how things are going?

I feel a lot better than what I did this time last year. This time last year, I was miserable. It was weird when we started this record, a friend of mine passed away. And I had a lot more questions. This time last year it wasn’t okay. It wasn’t good, but I still just kept digging in. And finally, this past year, this January, I asked for help with all those questions that I still had from writing the record, and what I thought about over the past year. I sought treatment and got help. I guess what I’m saying is, if somebody comes across this and hears this story, all I can say is, if you’re going through some shit, it’s OK to ask questions. It’s OK to feel bad, but go get some help. Help is out there. Help works.

Photo credit: Joshua Black Wilkins

Ian Noe Finds Carnage and Compassion in ‘Between the Country’

Folk rocker Ian Noe captures both beauty and ugliness on his debut album, Between the Country, populating his isolated Eastern Kentucky home with vivid portraits of human carnage.

Heavily influenced by John Prine, the 29-year-old writes with insight and deep compassion for what some might describe as the dregs of society. Meth-addled junkies, alcoholic drifters, and the gangs that prey on them dominate his songs, but he says shock and awe has never been his real goal. Instead, it’s to write songs reflecting the hardscrabble truth of his hometown. It’s a great place to grow up, he explains, but there’s no denying the dark reality which lurks down almost every holler.

“I guess it’s just the environment and the stuff you see growing up in Eastern Kentucky,” Noe says of his inspiration. “There’s a vibe to it. I hate to be so vague, but there’s a definite vibe.”

Noe has articulated that vibe so well he was invited to serenade Prine during a pre-Grammy Awards tribute at Los Angeles’ iconic Troubadour in February, and this summer he’ll open a series of shows for the legend in Europe. But for now he’s touring the U.S. with a batch of tunes that make traditional murder ballads sound like lullabies.

Noe spoke with The Bluegrass Situation about his admiration for Prine’s work and how it led to Between the Country, as well as his connection to the doomed souls of his songs and producer Dave Cobb’s help in creating a full-band sound.

BGS: Your vocal and the literary quality of the lyrics remind me of John Prine, which I’m sure you get a lot. How big of an influence was he on you?

Noe: Oh, he was huge. I would have to say he’s definitely the biggest influence for me. I started out wanting to be Chuck Berry on guitar, but it didn’t take me long to realize I wasn’t Chuck Berry. [Laughs] Then I heard John Prine through my dad, who would play his songs all the time in between Merle Haggard and Neil Young. But when he went to Prine songs, they would stick out … and I was just obsessed ever since.

What was it that stuck out about Prine?

He can just take simple things and make them profound. He’s the best at that. He can look at a sidewalk and write a song about it, make you laugh and think at the same time.

You’ve done something similar with Between the Country, but there’s a lot of dark themes – songs about substance abuse and self-destructive behavior. Why are those topics given so much prominence in your own writing?

I imagine it would have to be all the stories and people I know, as well as people I didn’t know but heard stories about. Just stuff that you hear happening in a town of six or seven thousand. Lee County is not that big, and it’s a cliché, but you hear everything that goes on in a small town.

Were you exposed to that stuff personally?

Not really, to be honest. I never did go to a meth house or anything like that, or even see anybody using it. But it’s one of those not-really secrets. Everybody knows it’s around.

I think that’s interesting because you seem so good at getting into these characters’ skin. How do you make that happen without first-hand knowledge?

I just think about them. Just think about it and picture in my head how it might be to live that way. It starts with a melody. I like to get the melody going in my head and if it’s a good one, try to see what’s going on with it.

I guess what I’m getting at is even though there’s bad stuff going on, it never seems like you’re judging anyone, or the area, for it.

Yeah, I tried to be real careful not to do that or come off as holier than thou. “Meth Head” is harsh, but I just wanted to be as extreme as I could be because it’s such an extreme drug, you know?

Tell me about coming up with that song. It’s really specific, I mean the imagery of this guy hunting for scrap metal and the woman covered in sores is chilling.

That song used to be about a war hero who was coming home, or at least the melody did anyway. I thought I was wasting the melody because I had already written some songs about battlefields and stuff like that, so I scrapped all of that and started again with the melody. I came up with that first verse pretty quick and just kept going.

How did you get so vivid with it?

It just comes with there being an actual junkyard in Lee County and thinking about the sound of the junkyard, thinking about the rest area that’s down the road and all the smells and sounds, things like that, just trying to get as descriptive as I could be.

Tell me about the title track. What does that phrase, “Between the Country,” mean to you?

Just being in the country, and everything that’s going on in between it. In between this hill or mountain, or what’s going on up in this holler, that’s what it means.

Why did you decide on that for the title track?

My grandmother used to say stuff like “If you treat your parents well, your days will be long on this earth,” which I’m not saying right but it’s from the Bible. She used to say stuff like that all the time, and I got to thinking about it, like “On down between the country, where deer lay along the road / On down between the country, where a long life’s a blessed one, I’m told.” It was like some people don’t make it past 40, you know? And that’s everywhere, it’s not just in a small town. But I didn’t grow up everywhere. I grew up in Lee County.

“Irene (Raving Bomb)” is about an alcoholic who’s not hiding it so well, even though she seems to think she is. How hard is it for you to find compassion for a character like that?

Not hard at all. We’ve all had our issues with this or that or the other, and I grew up seeing a lot of things like that. It wasn’t hard to have compassion for somebody whose disposition turns them to something like that.

How about “Letter to Madeline”? It’s about this guy who’s on the run and he’s carrying a letter he never mailed. What’s his backstory?

I was and still am a big fan of [the FX series] Justified, and I think it’s season two or three where there’s a story arc about the Detroit Mafia. I wanted to make it sound as if it was older. “A Detroit general” just meant a Detroit Mafia boss, and then his company just refers to his gang. It just came from that and people like D.B. Cooper — thinking about somebody robbing this guy and him trying to make it back to Kentucky.

Tell me a little about the sound here. It’s got this mix of folk rock and even a touch of ‘70s psychedelia at times. I know you’ve mostly worked solo in the past but teamed up with Dave Cobb for the album. Did he have a big impact?

It was pretty natural and easy. We were going back and putting in some of the electric lead you hear on “Dead on the River,” and he had bought a specific amp from Carter Vintage [Guitars in Nashville] the day we were mixing and overdubbing, and I believe he said he’d been listening to The Byrds that week. It was off the cuff, but the tone fit the themes, if that makes sense. … I like that there’s not a whole lot of crazy guitar solos, but every one of them suits the song. We don’t have congas or whatever, and it just has enough to breathe. Anything we overdubbed didn’t get in the way of any of the stories.

What do you hope people will take away from this first record?

Like everybody always says, when you make an album you just want people to appreciate it as much as you appreciate it. You want them to listen from track one all the way to the last track, and not everybody does that, which is all right. But the subject matter is all a common theme through the whole thing, and the cohesiveness is important. That’s what I love about all my favorite albums.

Photo credit: Kyler Clark

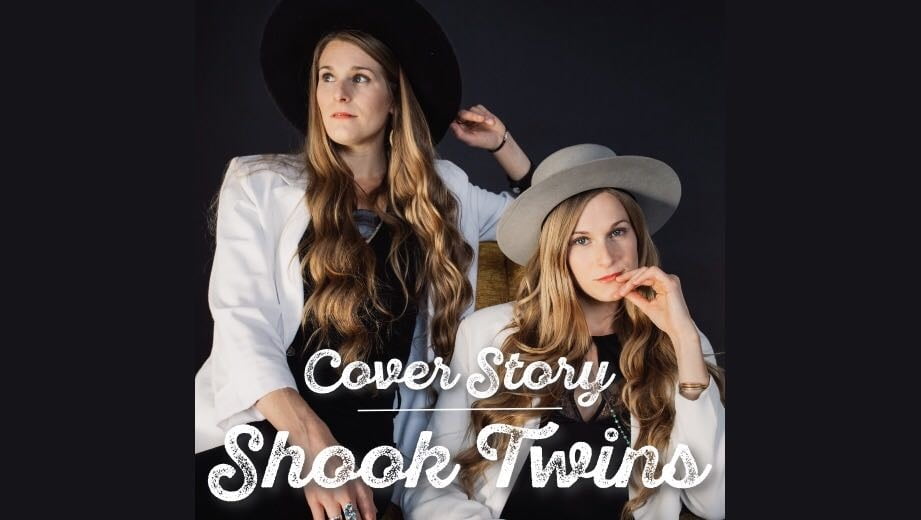

Shook Twins Pay Tribute to Honorable Men on ‘Some Good Lives’

Shook Twins — the duo composed of sisters Laurie and Katelyn Shook — have abided by the label “quirky” ever since they released their first album, You Can Have the Rest, in 2008. Their process of integrating unexpected sounds, looping, and multiple instruments (including a golden egg typically used for percussive flares) may seem unconventional, but those touches serve as thoughtful embellishments to elevate their honeyed voices.

On their new album, Some Good Lives, the Portland, Oregon-based musicians put those voices to use in praise of good men. At a time when women’s narratives have increasingly come to the fore, Shook Twins instead focus on the positive influence certain men have had on their lives. The choice suggests there’s room to strike a balance, rather than cast one gender aside to uplift another.

Following in the footsteps of their archivist grandmother, Some Good Lives is an amalgamation five years in the making — a blend of original songs and “found sound,” of a sort. Katelyn spoke to the Bluegrass Situation about the band’s new project.

BGS: Your grandfather played piano — you even include a clip of it on the album. So it seems like you have music in your blood.

Katelyn Shook: Yeah, that was our first musical experience. We’d go over to their house and lie under his grand piano. He was totally untrained, just [flying by] the seat of his pants. That’s why I had to put those snippets on there, because it’s so Grandpa. We started singing really young and fell in love with it. We chose to be in choir but we didn’t pick up instruments until we were 17.

“Grandpa Piano” and “Moonlight Sonata” aren’t really “found sound” pieces, but they provide an interesting texture to the tracks that you wrote. What was the thinking behind including those?

I wanted to sprinkle those in because it goes with the theme of Some Good Lives. I realized that a lot of the songs were about somebody or dedicated to somebody, and all of them happened to be men, which blew my mind. I was resistant to it at first, like, “Now is not the age of man!” I just wanted to honor women. But then I had to realize and keep in check that there’s a balance, and we need to remember and honor the good men in everybody’s lives.

We’d grown up with such good men, and that’s what made my life so balanced. Most of them have passed away, except for two, so I sprinkled in “Grandpa Piano” because there was not really a song dedicated to my grandpa, but he was such a big musical influence on us.

Considering that so many people want to make room for new stories, how have you made the case that now is a time to also share stories about men, even if they’re positive?

I don’t know. I don’t know that I’ve made that case. We’ve always lived by example, and talking with all the women around me, I honestly feel like Laurie and I are very rare in our generation to have such positive male impacts in our lives. It’s funny when a theme pops up. It’s not like we went into this record like, “We want to honor the good men.” It just came out.

On “Dog Beach,” which was originally written by your grandfather Ted, you added your harmonies to an old recording. How did you retain that original, almost old-timey sound quality?

That song is a trip! It’s a long story, but I’ll try to keep it short. My grandma was an archivist, and she had this tape recorder always going. Anytime we had a campfire with our family, we made [Ted] play that song, and he was always resistant to it because he never thought it was a great song. But it was the only one he ever wrote. Ted passed away in 2015 from this massive, traumatic heart attack out of the blue. It was terrifying, horrible. After he passed away, my dad was listening through those tapes, and we heard “Dog Beach” on there. We didn’t even know it’d been recorded — Laurie and I were 5 at the time.

I heard that, and I got the idea to sing this with him one last time. We were in Portland, and we had a whole bunch of friends over— including his ex-wife and his daughter, who’s our best friend — and I had the tape with me and a shitty tape player. I put it in to play it, and we’d sing along and record it. I hit play and it ate the tape. I was like, “No!” But I knew it wasn’t the only copy — we had another one at home — so I called my boyfriend, woke him up (because he was staying with my parents), and I made him go inside with my dad and look for this extra tape. They found the other tape, they found a tape player, put it in there, and it ate the tape.

It sounds like at this point Ted didn’t want you to share it.

Exactly, but I knew he was just fucking with us because he was always resistant to playing it at campfires. So they took the tape out and they put it together — it didn’t break, it just unwound. Then my boyfriend went to sit in the car, which was the only other tape player we had at the house. If you go back and listen to his recording, you can hear his puffy coat rustling. He’s in the car just voice memoing it on his iPhone, and then he emails me the voice memo, and we play the voice memo in the living room. This all took an hour. It’s emailed through time and space. I don’t know, it’s the way it worked out. It was such a crazy night.

What was the recording process like? I know it took a few years to get to that place after your last album, but it seems like it was worth that wait.

This process was a lot different. We normally block 20 days, and we go to the studio and knock it all out. But this time we took our sweet-ass time. We did it in several chunks. We’d been playing these songs live, and we might choose not to do that with our next album, but I really like to because it lets the song marinate. We recorded three songs first and then we’d listen back to them, and since we’d been playing them live, we added more stuff to it. It was a cool way to do it but it took forever.

I think “Vessels” might be one of my favorites on the new album, both for the message and for the vocals.

That one is really special to us, too. It’s dedicated to one of the men who’s still alive, but he has a brain tumor. We wrote it right after we found out he had it.

Is he around your age?

He’s four years older, but he’s super healthy and super young. It’s super nuts. When we wrote it, we were still in that phase where he could die at any moment. It’s a really gnarly brain tumor. Nobody survives this. It’s a total miracle that he’s come this far — it’s been like five years now. But we were in this state of shock and terror, we had our moments of coming to grips with it. That song was us accepting that we’re just vessels, and we have to say goodbye sometimes, and we have to be thankful that we got you at all. It’s narrow, singing to him, but it’s a broad statement to everybody about accepting your death, your friend’s death, and finding a way to be ok with it.

Vocally, we really like what Laurie did. That’s another song that Gregory Alan Isakov helped out on. She took four songs to him. She repeats lines, talking; I really like that effect because it made it this ghostly statement. Isakov helped make it sound more vibey; we call it adding “God noise,” where he adds all this weird ass-shit, and he tweaks it in Pro Tools, but the stuff he comes up with, he’s a total genius. His essence, his God noise, made that song extra special for sure.

Familial harmonies have their own kind of magic, but as twins you have similar vocal cords, which seems like it could pose a challenge at times. What kind of thought process have you put into your arrangements?

We use that vocal identicalness to our advantage. We’ve started to experiment with more unison singing. It’s trippy because people try to achieve that in the studio, where they double themselves, and you can’t really tell there’s two tracks, but there’s an essence. That’s what it sounds like. Harmony-wise, it’s mostly Laurie; it just comes out of her. When we analyze it, sometimes we’ll totally overlap and all of a sudden one voice will naturally go lower and one will go higher. We don’t do the typical harmony. We intertwine. It’s very trippy.

As twins, how have you managed to forge a sense of individuality in the duo?

It sounds weird, but it’s never been an issue to express ourselves individually. We’ve always been Shook Twins. We actually strive to be more of a duo. Sometimes we play solo and it doesn’t feel right; we don’t enjoy it as much. I think we’re definitely strongest together. We’ve never had a competition issue. We always say, “We’re the twin-iest twins we know.” Most times we meet other twins and they all have their own lives. It’s kind of weird to us. We’ve always had the exact mindset about everything. It’s crazy.

The Show On The Road – KOLARS

This week on the show, Z. talks to Rob Kolar and Lauren Brown of theatrical space-rock duo KOLARS.

LISTEN: APPLE PODCASTS • MP3

Sure, many husband and wife bands try to stand out in their own way, but Rob and Lauren take it one step further. They’re both multi-talented multi-instrumentalists who create a sci-fi-inspired, jangly, joyful strain of roots rock that sounds much bigger than two people. Sometimes you just have to hear something to believe it.

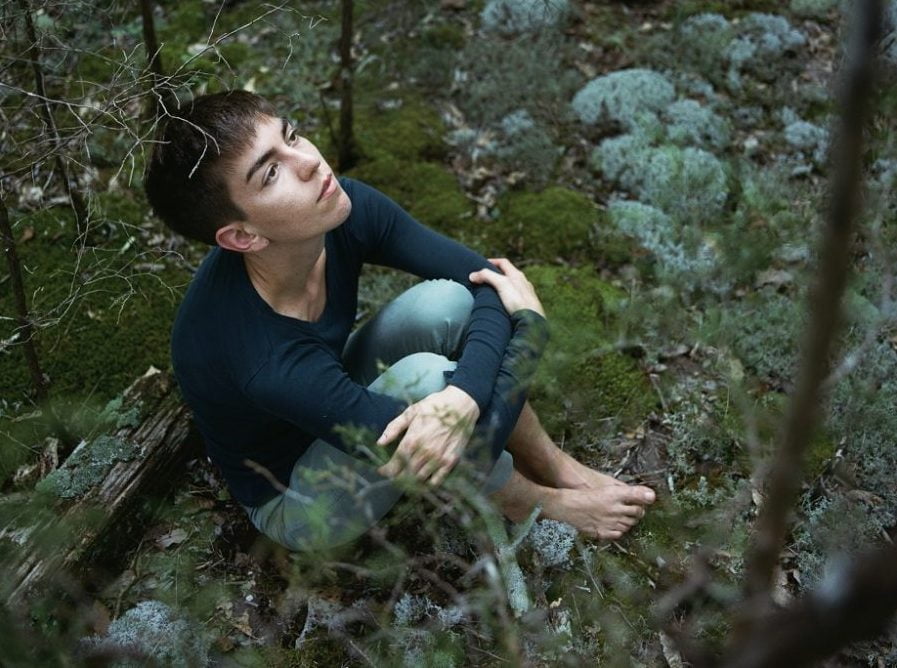

STREAM: Maya de Vitry, ‘Adaptations’

Beginning in 2016, The Stray Birds’ fiddler and vocalist Maya de Vitry found herself writing songs that didn’t fit with the band’s aesthetic. At the time, the prospect felt confusing, even a touch frightening. “It was really scary because I didn’t know what that meant,” she says over the phone from Pennsylvania. “The band was all consuming.” De Vitry had been performing with the The Stray Birds for nearly a decade, releasing — at the time — four albums and an EP. What were these songs, if not for them?

As it turns out, her solo debut Adaptations moves away from the sound — and structures — that defined her folk and traditional inclinations with The Stray Birds. Producer Dan Knobler and a backing rock band layer each song with flourishes of electric guitar phrasing and soft brushes on the drum, all of which open the door for de Vitry’s strikingly deep and at times stately voice to infiltrate new spaces. (Stream Adaptations at the end of this story.)

Writing for herself rather than a group, de Vitry’s lyrics lean towards inclusivity, humanity, and other unitive concepts. There are also themes of love, but not exactly the romantic kind. On “The Key” de Vitry writes about the necessity of friendship at a time when romance felt burdensome (she and The Stray Birds’ Oliver Craven had broken up following the release of the band’s 2016 album Magic Fire). Whatever misgivings de Vitry had about walking her own path, Adaptations showcases a remarkable voice set to scale new heights. As she sings on “Wilderness”: “It’s time to leave the trail behind.”

BGS: You’ve said that these songs emerged from a period of self-exile. Can you tell me a bit about that time?

de Vitry: When I first started songwriting when I was younger, it felt extremely vulnerable and scary to me. Around 2010, when I started playing with Oliver and Charlie and we made The Stray Birds, that was a really natural place for me to put my energy at the time.

You had the protection of the group.

Yeah, and I had the camaraderie of the group. I’m trying to figure out how I want to navigate telling the story because it’s hard. The group broke up, and I’m still processing how much I want to share.

So what was it like to write outside the bounds of the group?

In a way, making this record was revelatory to me. Writing these songs, being alone, insisting on space, and insisting on stopping the motion and commotion of being on the road with that band, that’s what I was craving. If you just keep moving, you think that’s the way you’re going to survive, that maybe things will change and you’ll find yourself in the right place. But writing the record and that self-exile took realizing that you can’t just keep moving. Sometimes you have to stop and look inward.

The exile was… I felt like I was doing something wrong by stepping away and doing something creative outside the band. Ultimately, it was a cocoon that needed to be exited. Now I feel really bright and strong — about the record and the place that I’ve come to. At the time, I felt I needed to escape. I was going to a land that was really unknown, which was myself.

There’s a sense of serendipity surrounding this project: You were supposed to go to Nashville and instead retreated to your grandparents’ cabin; then you were supposed to make a demo and instead recorded half of the album. What’s the most important takeaway you’ve learned as a result?

What I’m continuing to learn is that our bodies are at least a few steps ahead of where our brains are. Our instincts and our gut feelings — the way that we’re sometimes physically pulled towards things — you can’t explain it. It sounds kind of out there, but I think I’ve learned to trust intuition a little more. That’s important to me in thinking about being. Paying attention to that.

It gets distilled into that opening line on “Wilderness”: “It’s time to leave the trail behind.”

As much as society or careers or trajectories—the dreams that we have for achievement—might be linear, I don’t think we can get away from the fact that we are actually a part of nature, so therefore we are sort of beholden to cycles, and we might have cycles of rest.

You share beautiful and necessary messages on “Anybody’s Friend,” “Slow Down,” “The Key,” etc. Why did these in particular register for you?

“The Key” I wrote while I was up at the cabin, for that first writing retreat session, and that one was really personal. It was a love song to a few friends of mine. I was feeling really thankful for friendship. It’s a heralded kind of love, but I was forgetting how important it had been to me. With friends you can grow apart and grow together. There’s a lot more gray areas that are accepted in friendship. At the time, I was really disenchanted with any kind of romantic relationship.

I went to Cuba in January of 2017. It was around the time of the inauguration in the U.S. and I was seeing this divisive language and leadership, and power over people. One of my friends [in Cuba] was so patient with my Spanish. I asked him why, and he was like, “I want to know you.” I think the temporariness of that, and “Take a deep breath and try to tell me what you’re trying to say in this language,” was such permission. I felt like I was experiencing the power of listening and the power of vulnerability. I was like, “That divisive power has nothing on this.” I think that’s how I was interpreting the world, in a hopeful way.

That makes sense. Even on “Go Tell a Bird,” it seems like the current political climate influenced those lyrics.

Yeah, and it’s not like I’m a perfect person. I guess I just wanted to challenge the language, and challenge the boxes, and challenge the idea of freedom.

Every song has such a different kind of soundscape compared to what we’ve heard from you before with The Stray Birds. When you got into the studio with your producer Dan Knobler, what was it like building each one?

Working with Dan was probably an interesting choice on my behalf. It wasn’t like I was really attached to some catalog of work that he’s done, though he’s got a great catalog of work as a producer and engineer. I was really just operating on this feeling I’d had. Before I’d asked him to produce, I was doing a compilation CD and The Stray Birds were a part of it. I was singing and the way he spoke to me about my voice and my phrasing, and the way we interacted while I was singing, I felt really heard in a new way. I never forgot that feeling.

How did he push your voice on this album?

I felt freer. The Stray Birds, as much as they weren’t strictly tied to a genre like folk or bluegrass, I think there was a certain dialect of singing that we did. Especially with harmony singing, the blend is dependent on how everyone is singing. With this, I felt the more I stepped into feeling free, the more Dan would be there to encourage that.

Also, with the sonic palette — the fullness that’s around it — that’s not an idea I had going into this. That is something I would really thank Dan for hearing. I was surprised when he said, “I think we should get some strings, and see what Russell Durham has to bring to these songs.” The band that we tracked it live with was pretty much just a rock band—upright bass, drums, and two guitars. Anthony da Costa has really tasteful electric guitar playing.

But there was no genre. There was nothing I was trying to prove. I wasn’t even really trying to make a record — it was supposed to be a demo. So it was very playful. Dan and I are really particular about songs, and I feel more and more if I can trust the song 100 percent and if the song feels indestructible to me and also very flexible then we can go play with it and it’s going to be fun. The studio was such a joyful time.

With The Stray Birds, endings themselves are naturally fraught, and obviously you’re still parsing through a lot of what took place there, but what are you proud of as you begin a new phase of your career?

I’m really proud of what we learned together, and our willingness to take risks together, and our willingness to just show up. Sometimes there was less reflection in what we were doing — there was more action. I’m really most proud of the last record that we made together.

It sounds like it was immensely collaborative.

Yes, that’s what I’m most proud of in that band. It’s a beautiful record. It was so difficult to write it, but it was so fulfilling to write it. Everyone’s voice is present in all the songs, melodically and lyrically. I think that record was the most empowering experience for everyone in the band.

Photo credit: Laura Partain