Though Lead Belly was merely a man, his story reads like the stuff of legends. He had multiple encounters with the law, was sentenced to a chain gang, escaped, killed a relative, and got thrown back in the hoosegow, earned himself a pardon because the governor was a fan. But then he stabbed someone else and got put back in prison, this time in Angola, where Alan and John Lomax found him. He was released, again, after serving his minimum and pleading with the governor, but committed a second stabbing, in the late ’30s. All the while, he so impressed everyone who heard him that he also landed himself in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Known primarily for playing 12-string guitar, Lead Belly also played the piano, mandolin, harmonica, violin, and diatonic accordion on the hundreds of songs he recorded over the course of his all-too-brief career.

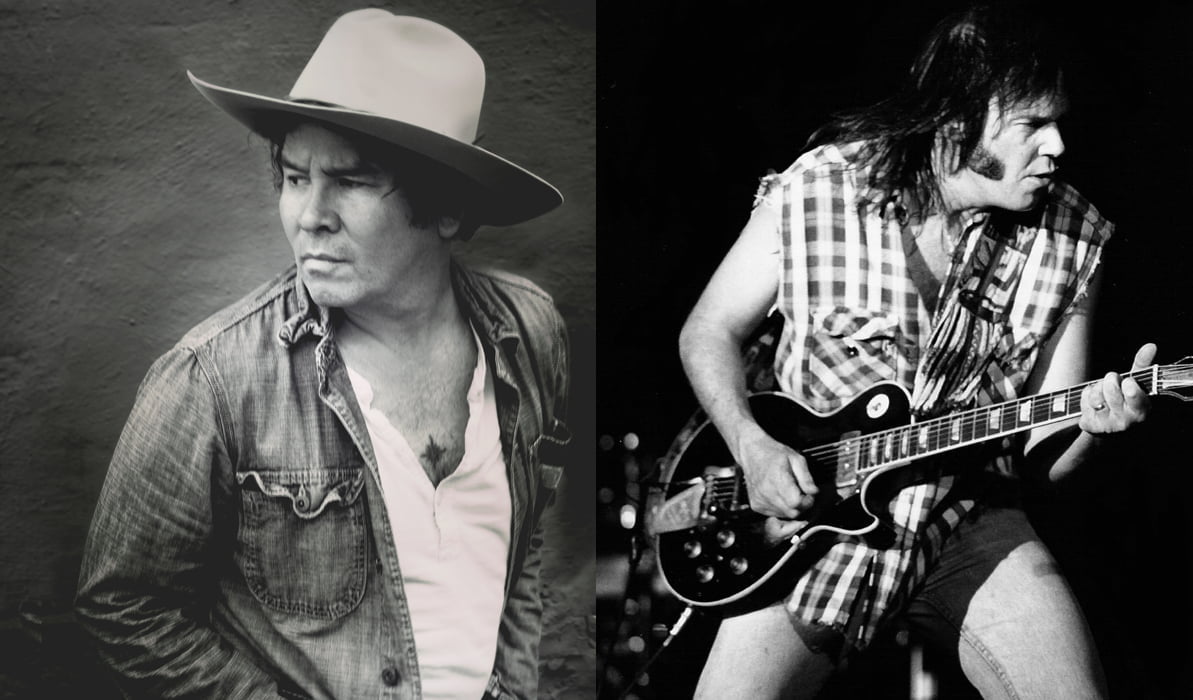

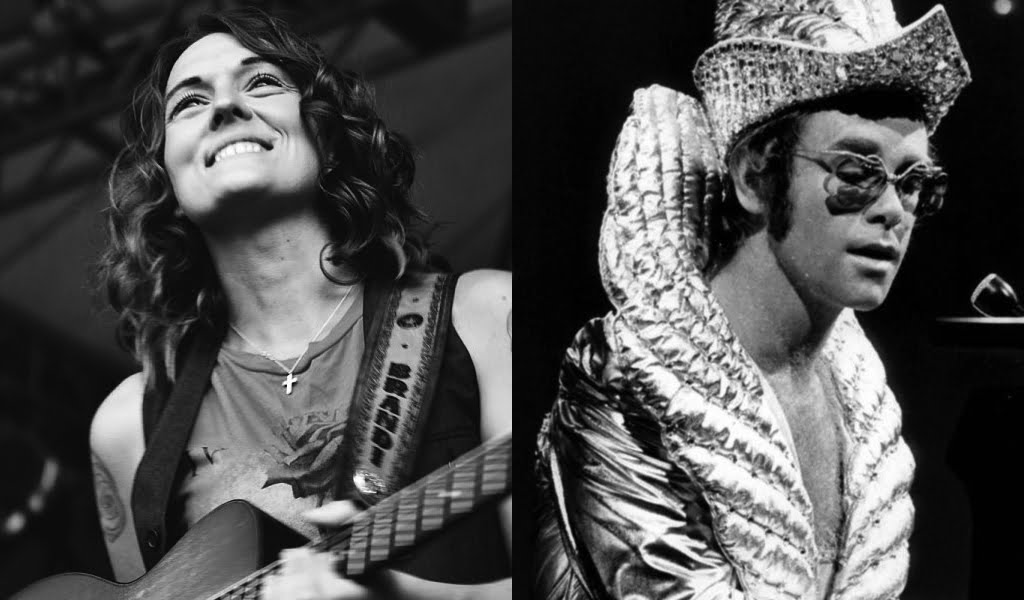

Texas songwriter Scott Biram grew up on those songs and, later, learned the stories that went with them. In his own bluesy, folky, soulful Americana style, Biram hears the inevitable echoes of Lead Belly coming through, including on his latest release, The Bad Testament. The influence is there in the miscegenation of musical styles, but also in the way Biram approaches his role as raconteur.

Why Lead Belly?

Well, Doc Watson was taken! [Laughs]

[Laughs] Fair point.

I would definitely say he’s among my biggest influences — Doc and Townes Van Zandt are my other two. Lead Belly has been in my life my whole life. My dad listened to him a lot when I was a kid. I have quite a few songs where I do a little rant in the middle, where it’s not really singing as much as it’s telling a little story or saying something. I think I got that from listening to Lead Belly.

Right. Must be nice to have parents who listened to cool music. I grew up on Barry Manilow and Dionne Warwick.

[Laughs] There was definitely a lot of Eagles and Crosby, Stills, and Nash at my house. But my dad listened to a lot of Doc Watson and Lightnin’ Hopkins and stuff like that.

I can see why he would gravitate toward that stuff. Lead Belly really did have a singular style — this mix of blues, folk, gospel, and country on a 12-string guitar. What was it that spoke to you in that mish-mosh or maybe it was the mish-mosh?

I think a lot of it had to do with just being a part of my life when I was a kid with my dad listening to it so much. We had this vinyl record that was the soundtrack to the film Lead Belly which is a pretty obscure movie, not really easy to find. I think they filmed it in ’76 or something like that. I was a little kid. They filmed it in the little town that I lived in and I was in my dad’s arms on the edge of the set while they were filming the scene where Lead Belly shot his friend and went to prison.

Well, one of the times he went to prison …

One of the times … yeah. [Laughs] So I heard that soundtrack a lot, which wasn’t actually Lead Belly playing on the soundtrack. It was Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee and someone named Hi Tide Harris who I haven’t been able to find too much on, even with the Internet.

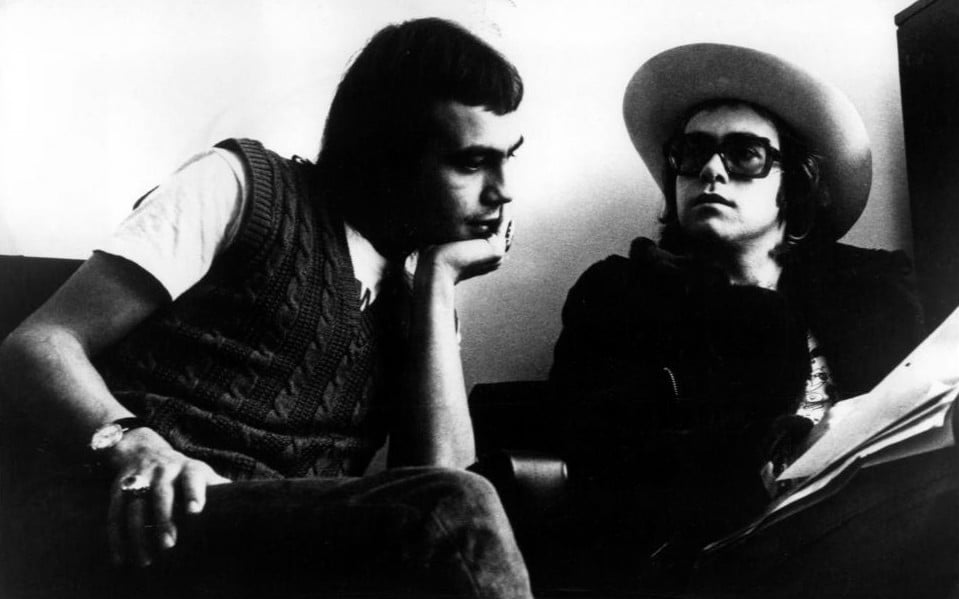

Once I got into roots music, when I was a little older and started playing bluegrass and started really playing the guitar a lot and learning blues, Lead Belly was just naturally somebody that I gravitated toward. And his story is so interesting. I read all the biographies. I read a lot of biographies on musicians that influence me so that I don’t just have a shallow knowledge of them. If I’m going to be playing some of their music, I want to definitely know as much about them as possible.

That’s awesome. I had never studied much of his life until prepping for this. But, I mean … the guy recorded hundreds of songs, worked with the Lomaxes, had a radio show on WNYC, went to Europe, and was in and out of prison multiple times — sang his way out of jail a couple times — all before dying at 50 or 51. That’s some hard living. Can you imagine spending even a couple years in his shoes?

No. [Laughs] I mean, I can imagine, but I’m probably not going to do a very good job of imagining what something like that would be like. I’m just a guitar player. [Laughs] Actually, he only sang himself out of prison once. There’s a legend about him that he sang himself out twice, but really, the second time was kind of exaggerated. I think he was in prison in Louisiana, at that time, and he got out on something called “good time” which is, I think, probably good behavior.

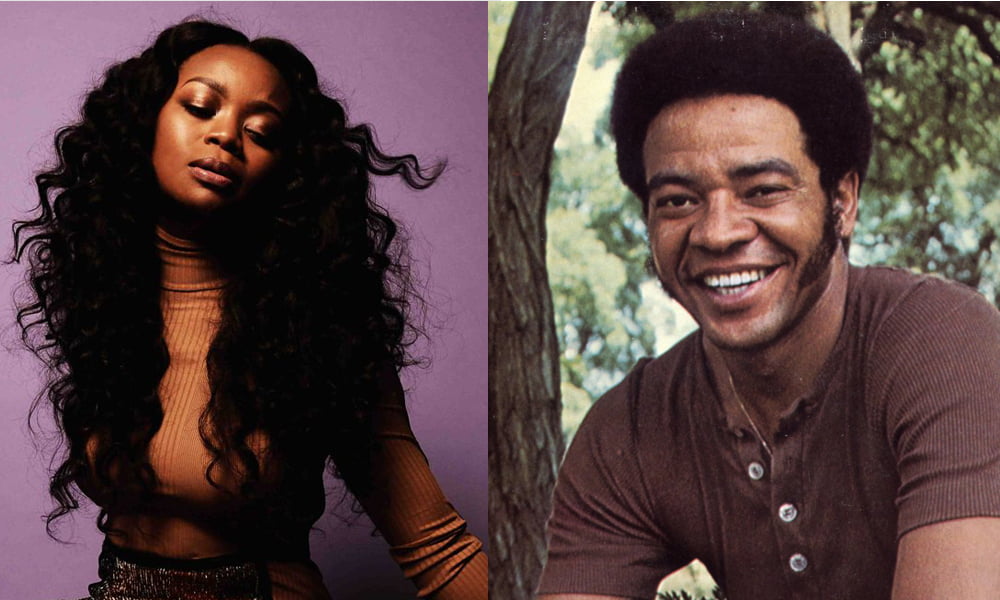

Right. He served his minimum and got out. Here was an interesting thing that I learned: He played at the Apollo, but the Harlem audience didn’t really resonate with him as deeply as the folkies did. He had a lot in common with Woody Guthrie, maybe more so than some of the old blues guys, but why do you think the Black audience didn’t connect?

First of all, he was a country guy. And I don’t mean country music; I mean from the rural South. So I’m not sure anyone from New York would really see it as anything but a spectacle, at that time. But, also, I wonder — and I’m just guessing here — I know that John Lomax used to kind of have him dressed up in a prison uniform and stuff like that, kind of clown him around out there and make him seem like he was just straight from the prison. I imagine that might have been a turn-off to some people in Harlem back then. I know Woody Guthrie, when he went to New York and was supposed to be on something and they wanted him to dress, as he described it, “as a clown,” he said he’d be back in a few minutes, went downstairs, and left. Didn’t even come back to the studio. [Laughs]

[Laughs] Yeah. I read that Life magazine did a three-page spread on Lead Belly and the title of the article is not something I’m going to repeat.

Yeah, I get ya.

And it was considered an honor that he was getting this prominent placement. But it makes sense that the minstrel thing wouldn’t fly.

It might’ve been a turn-off to people in Harlem. If there was anyone from the South who lived in Harlem at that time, they probably weren’t impressed by it because, to them, it was just a reminder of what they just left.

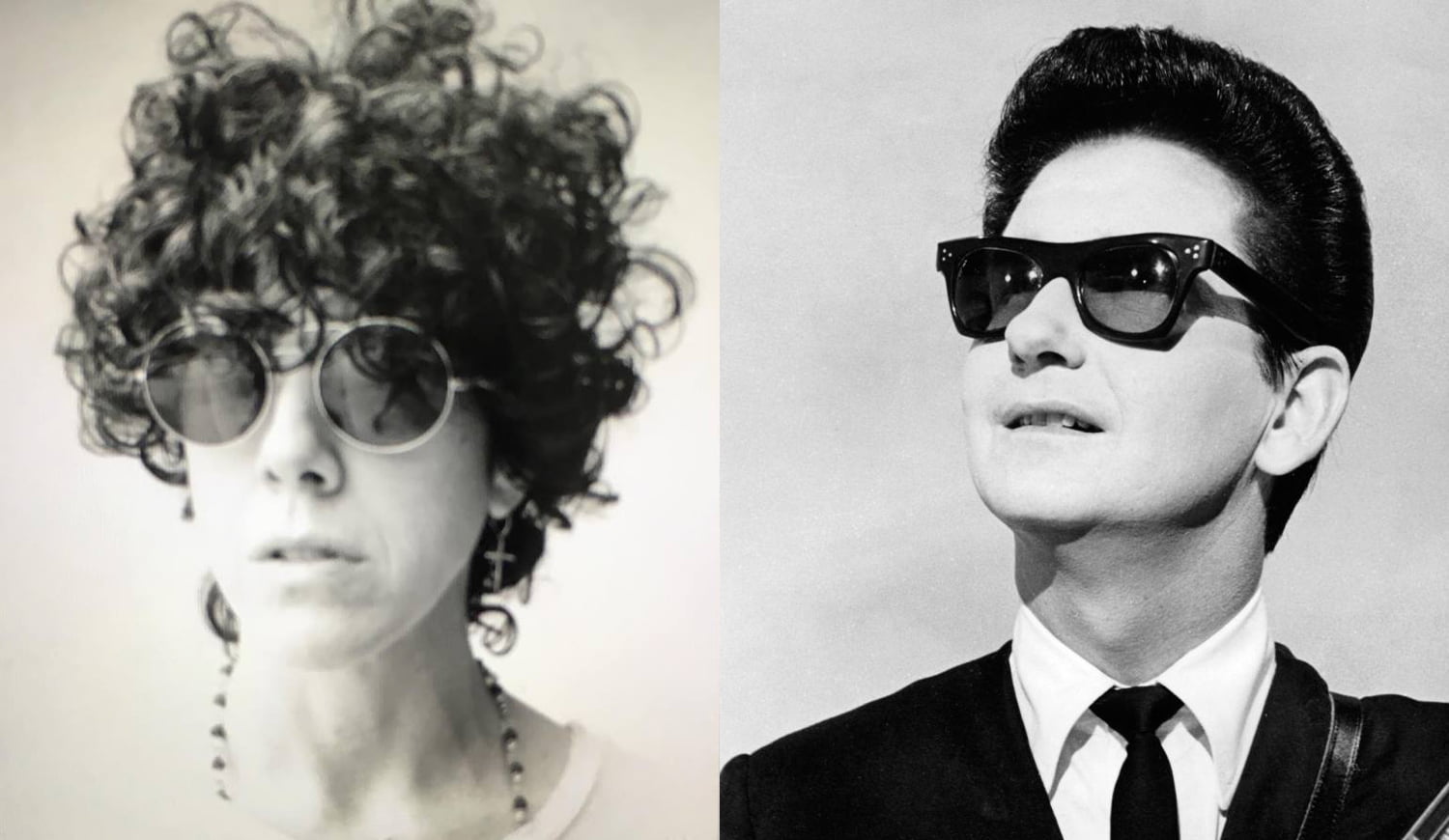

The other thing I love about listening to his stuff and pouring over his stories is that he lived through an era of history that was rife with huge moments and he documented history as it happened, writing songs about the Titanic, the Hindenburg, Jim Crow, FDR, Hitler, etc. Pete Seeger carried his style forward. Bob Dylan, to a certain extent. Who else do you hear carrying the Lead Belly torch?

You mean documenting history as it happens?

Yeah. Ani DiFranco does a bit, which she picked up from Pete Seeger.

Honestly, nobody comes to mind that is documenting current events in music so much that it’s actual historical stories in the songs. There are a lot of people saying their thoughts about the current states of everything, but I can’t think of anyone that actually sings a story about a tragedy.

Santiago Jiménez, Jr. — Flaco Jiménez’s brother — has a record called El Corrido de Esequiel Hernandez: Tragedia de Redford. The album is titled after the song about a kid in Redford, Texas, down in the desert on the border, who was walking his goats one day and the guys in the DEA or Border Patrol came and shot him because he had a rifle walking, like he did every day, with his goats. He was basically a shepherd and he got shot. That’s the only one I can think of that pops out and that’s not a popular artist or anything. [Laughs]

[Laughs] Right. I was just thinking Hurray for the Riff Raff does it a little bit. Rhiannon Giddens, a little. But no one to the same extent. I mean, if you read Lead Belly’s song titles, you can trace history.

A lot of the time you have to listen to it as “The Hindenburg Disaster, Part I” and “Part II” because they couldn’t fit the whole song on the single. They had to put it on both sides!