“I have a big gun safe next to my desk….”

When a tale starts with those words, you know it’s going to be interesting. But it’s not what you might first think. This safe didn’t contain the weapon for a hunt. It held the prey.

Let’s let the speaker continue:

“…where I keep all the CDs people give me, but can’t listen to them all.”

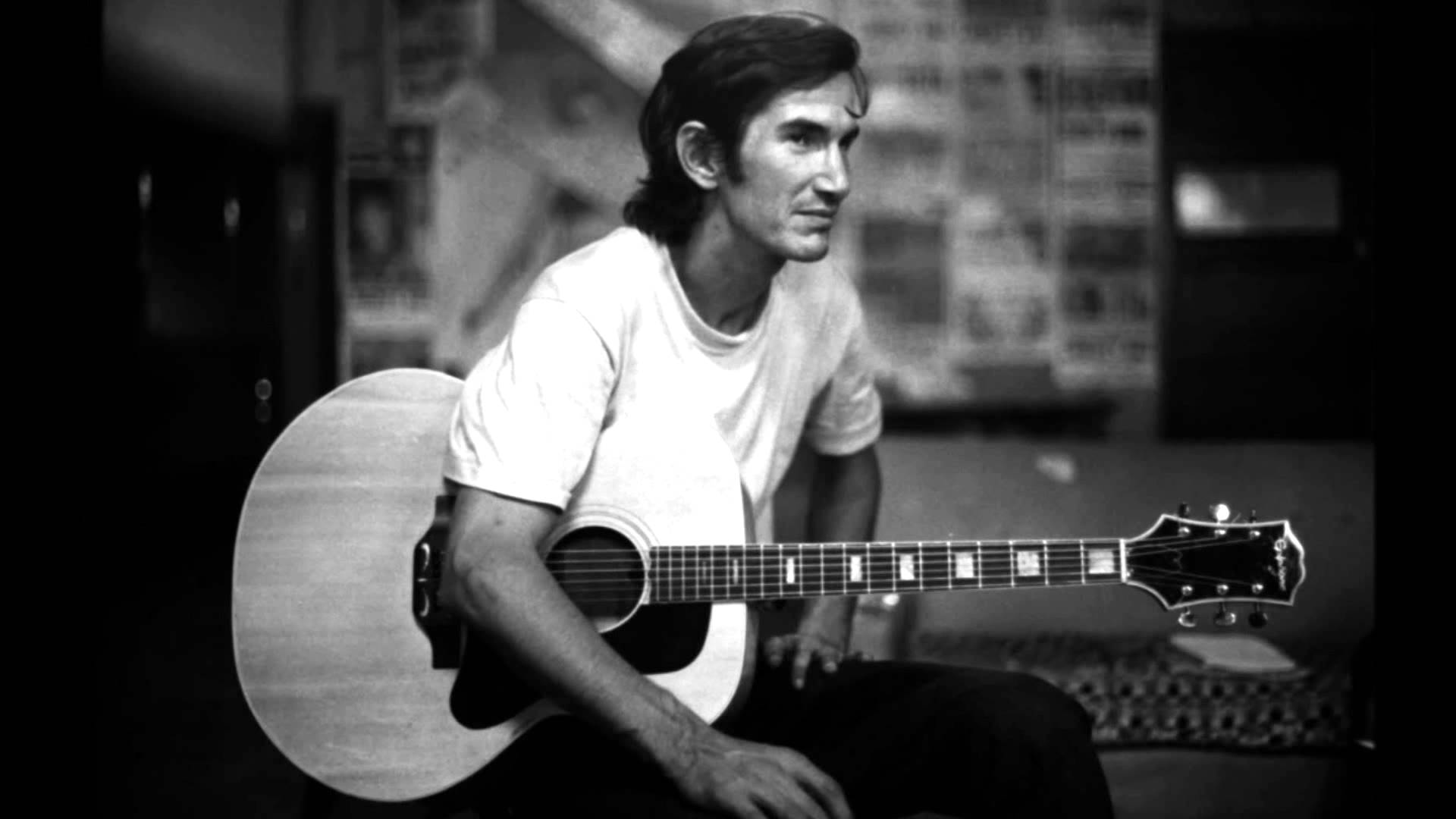

That’s Jeanene Van Zandt, who was married to the late Texas singer-songwriter Townes Van Zandt. Inside that gun safe in her Nashville home was also a disc containing “lost” recordings Townes made in a friend’s basement studio in the early 1970s. And on that disc were two songs for which she had been hunting around the world for years — as well as what may be the first recorded versions of Townes’ most famous song, the ballad “Pancho and Lefty,” and another favorite, “Rex’s Blues.”

Now 11 songs from that disc, including those four, have been put together for the album Sky Blue, the title coming from one of the previously unheard selections. On March 7, the set was released on his family’s TVZ Records via Fat Possum, on the 75th anniversary of Townes’ birth. And it comes at a time when a new generation — the fourth, by Jeanene’s calculations — is coming to discover Van Zandt’s music, even if some don’t know that he died in 1997 after years of issues with substances and mental health.

“I still get letters from people who have no idea he’s dead,” says Jeanene, who is also executor of Townes’ literary estate. “Things like, ‘We’re working on this tour and heard your music.’ I have to say, ‘Sorry to inform you that he died 22 years ago.’”

Since Townes died, Jeanene has spent a lot of time and effort tracking down recordings he’d made and never-released songs in his rather itinerant life. It’s been a dedicated effort of tracing rumors, following document trails, seeking out his friends and acquaintances, and/or just going with intuition, sometimes paying off, but often finding dead ends.

The current discovery was made by Will Van Zandt, her son with Townes, who took it upon himself to go through the stored material. One of them was a disc simply labeled “1973,” given to Jeanene a while back by Van Zandt’s longtime friend, Atlanta-based journalist Bill Hedgepeth, who had a little studio in the basement of his home where the singer would sometimes record things on which he was working.

“Will came and took some of the discs and had a box of them in his closet and kept telling me about some of the recordings and I said, ‘Bring ‘em!’” she says. “There have been certain missing songs I had looked for for years. Townes would say, ‘I know they’re out there! Find them!’ Over the years I’d stumble across lost songs here and there. And there are two on this one! Two songs I’d scoured the world for.”

“Sky Blue” and “All I Need,” the other missing song, are prime examples of the mix of sorrow and sharp character portrayals plied with starkly economic language that stand as Van Zandt’s artistic signatures. But there’s much more to be treasured on this set, including what may be the first recording he made of “Pancho and Lefty.” That song was made familiar to many when Emmylou Harris recorded it in 1977, and to many more in 1983 when a duet by Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard took it to No. 1 on the country charts, cementing Van Zandt’s stature as a premiere folk songwriter of that era. Townes himself has a cameo in the pair’s video.

Among the others on the album are deeply caring versions of the folk song “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” and the murder ballad “Hills of Roane County,” plus tributes to fellow songwriters Richard Dobson with “Forever For Always For Certain” and Tom Paxton with a gorgeous “The Last Thing on My Mind,” which is a perfect closer for the new collection.

That there have been so many songs and recordings to be tracked down is a reflection of Van Zandt’s scattered life. The actual dates of these recordings may have come over the course of several years in the early ’70s, a time when he was living variously in Texas, Colorado, and Tennessee, at least when he settled down at all from his wanderlust. He released six albums in that time and had some tentative success, but nothing solid.

Hedgepeth’s home studio, though, was a refuge for Van Zandt, where he felt free to try out songs.

“They were very good friends and he was a very nice man,” Jeanene says. “When Townes would play Hot ‘Lanta he would stay with Bill. Listening to the tapes I’d hear Townes saying, ‘I want this here or that on here.’ So he was working on some project of some sort. Don’t know if this was one sitting or different trips.”

There’s enough variation of sound from song to song that it’s reasonable to assume that it was not all done at one time, but what ties them together is a sense of freedom to express, to try out songs, to sing some things he loved and see how they worked.

“There were 27 tracks, some were repeats, one with a dog barking in the middle, another with the phone ringing,” Jeanene says. “Once we whittled them down we thought, ‘This sounds like a family of songs.’”

A little cleaning up was needed, but the raw unguardedness shines with Van Zandt’s masterful songwriting, guitar playing and singing, connecting the dots between his own spare style and the traditions he revered.

Townes’ own legacy is secure, with dozens of notable artists having recorded his songs and been inspired by his writing, prominently Steve Earle, who not only made a whole album of Van Zandt songs in 2009, but named his son Justin Townes Earle. Others are finding their way to Townes’ music with other new avenues of exposure. Recently Charlie Sexton played him in the movie Blaze, about mercurial singer-songwriter Blaze Foley, a close friend/running partner of Van Zandt and even more of a cult figure.

“[Sexton] was so nervous when they were filming that,” she says. “He knew I’d be there. I came up to him and said, ‘You did fabulous!’”

Townes also figures in the Foley episode of the animated Tales From the Tour Bus series from 2017, in which Jeanene appears sharing her reminiscences of some, uh, colorful exploits.

Katie Belle Van Zandt, daughter of Jeanene and Townes, has found many big fans among her contemporaries.

“I have quite a few friends of the same type of lifestyle that he was living at that age,” says Katie Belle, who is not a musician herself. “There are a lot of musicians around my age, in their 20s, hopping trains and traveling, busking on the road and such, making real folk music.”

A few weeks ago she had the opportunity to play the new release for her friends Benjamin Tod and Ashley Mae of the Lost Dog Street Band and another musician, Matt Heckler, who often travels with them.

“They were the first people I played this to,” she says. “They loved it. They thought it was beautiful. Ben said it reminded him of what songwriting’s about.”

For Katie Belle, the sorrow is what comes through most strongly, but also a sense of life in him that she largely missed, as she didn’t get much time with him.

“The very end of ‘Sky Blue,’ the first time I heard it, where he talks about how he longs to be the sun and longs to be the moon, made me tear up,” she says. “It’s beautiful. When my dad passed away I was really young, and when I get new music I hadn’t heard by him, it’s like wearing another piece of him.”

Jeanene Van Zandt is gratified, but not at all surprised, that her ongoing efforts to get her husband’s music to the world, both old releases and new discoveries, is having impact.

“I don’t think there’s going to be a human who can’t identify with these songs, whether 50 years from now or yesterday,” she says. “He was a master of the English language, studied people — in fact a little naughty doing it. He would push buttons and see what reactions he could get out of people and a lot of times they’d be jumping up and down and trying to kill each other and he would giggle and think it was funny as hell.”

And if some people hear him for the first time with this new release, that’s great too, she says.

“He’s not shrinking away,” she says. “I’m pretty sure there will be a fifth, sixth, seventh generation who will try to get ahold of him to go on tour with them.”