American music and dance have always gone hand-in-hand. Immigrants, bringing their folk traditions, art, and music to North America, combined and cross-pollinated with and stole and borrowed from the art and music of Native Americans, African Slaves, and African Americans. In that beautiful, conflicted, human, melting pot way we arrived at the incredible roots genres of our modern time. Dance had always been an integral part of that reckoning, of the growth, adaptation, and molding of our country’s vernacular music, but at the advent of the recording industry and the commercialization of music, musical dance and percussive dance were left by the wayside. They fell from ubiquity and popularity, largely relegated to preservationist, folklorist, familial, and rural niches.

Nic Gareiss doesn’t believe that dance belongs in those shadowed corners of our musical realms. A percussive dancer, scholar, and ethnochoreologist (think ethnomusicologist, but for dance — choreography), Gareiss devotes his creativity to bringing dance as music back into the traditional and vernacular genres that have slowly but surely lost nearly all of its influence. In the process, he explores greater ideas about his listeners’ and audiences’ expectations about the relationships of dance and melody, dancer and musician, dance partner and dance partner, song and singer, and performer and audience. Not only does he “queer” dance, by stripping it of its normative trappings, and laying its essentials bare, he also queers its heteronormativity, its patriarchal tendencies, and its binaryism — in a fashion that’s supremely gorgeous to both the ears and the eyes.

A good starting point would just be that we’re a music site, right? We cover music, not so much dance. Some readers might need a quick briefing on your mantra that “dance is music.” Can you give people a quick 101 on your worldview that dance is something that’s essential to music, not just tangential to it?

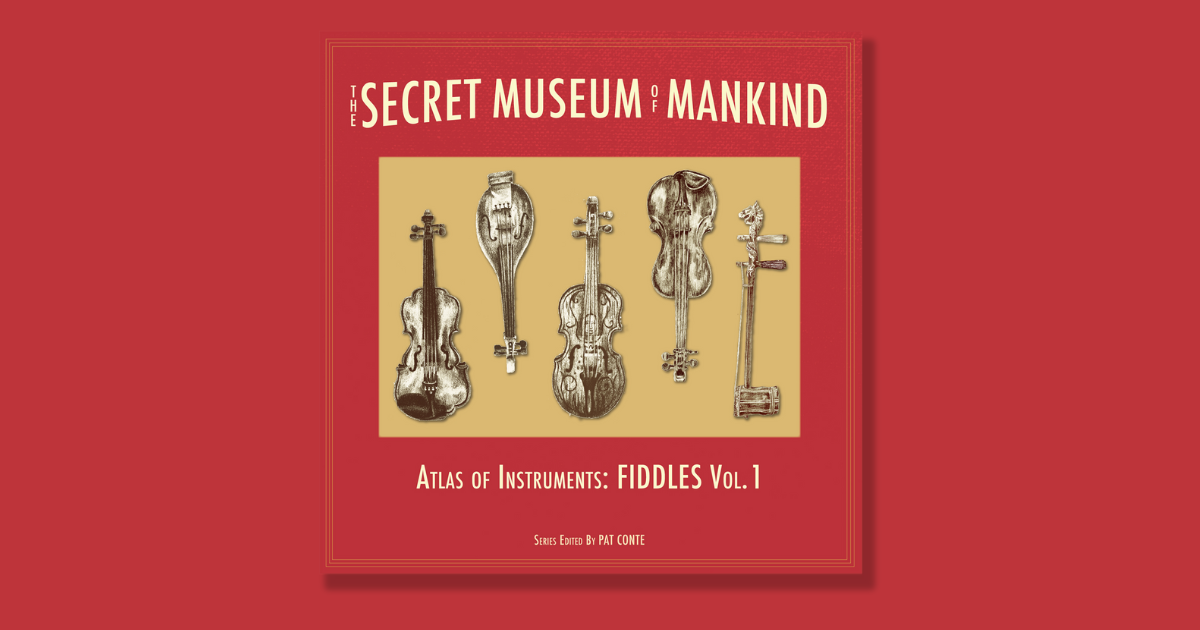

I work as a dancer who makes sound. The traditions that I study and continue to study — and love — are dance traditions that are percussive. Whether that’s Appalachian clogging, Irish step dancing, or step dance from Canada, all of these dance forms have as their impetus rhythm-making with the feet and body. Also characteristic of these styles is the fact that they occur in environments where traditional music is being played. One might actually argue, and I would probably puckishly argue, that the soundscape that’s created by dancers is actually as much a part of the soundscape of traditional music as someone playing a fiddle or a banjo.

It’s interesting that that is an extant truth about vernacular music — especially American vernacular musics — but the way that American music has grown and evolved, it’s extirpated dance from itself, and then brought it back in, in different ways.

I think that because of the commercialization of music over the years, especially because of recording technology, dance hasn’t had as prominent a role, sonically. For some reason people didn’t think that the sound of a moving body was worth recording as much as the sound of another moving body, but holding a guitar. [Chuckles] What I’m interested in doing as I work mostly with musicians, and usually musicians that come from folk music backgrounds of some kind, is creating dance for listening. That manifests in mostly concerts, but also in some recordings, some teaching, some lecturing — there are a lot of things that make up my year along those lines.

One of those things is Solo Square Dance, a show that you’ve worked up, which strips away all of the old-time music and folk music that’s a part of these forms of dance and just showcases the actual, physical dancing — the part that had been lost, perhaps due to that commercialization, like you were just saying.

Exactly. In Solo Square Dance there are no musicians, except for me! [Laughs] There are no sounds except the sounds that I create myself, using my voice, using my feet, snapping my fingers, whistling. The idea is to reference and pay homage to traditional music and dance as a symbiotic entity. Because I don’t play instruments in that show, that means that traditional music shows up almost as a specter, or as a concept of something that’s been erased, so you can still feel a trace of it. It’s not just the idea of traditional music as a nebulous canon of the music writ large. Instead, there are actually specific pieces of music that come from, say, the fiddle playing of Tommy Jarrell or a traditional Irish dance tune that shows up in a tribute to one of my Irish dance teachers. There is various music in the show, it’s just music as made through a sounding body without a prosthesis, without an instrument.

Something that you’re also digging into with Solo Square Dance is leaving behind a whole host of presuppositions and expectations about dance, but you specifically call out heteronormativity. There are so many layers here, because you have to unpack that dance is music, and that it’s always been an integral part of these musical styles, but then you have to unpack that dance is inherently heteronormative, too. That’s a lot of ground to cover! The interesting thing for me came out of these video clips of Bascom Lamar Lunsford dancing on the porch, in this film by David Hoffman that was shot in 1962. [In the film] Bascom is demonstrating what it would be like to be in a square dance, but he only has one body to do it, instead of the usual eight people that it takes to make up a square. I saw that and thought that that was kind of inherently lonely and beautiful. But also, it somehow simultaneously was merry and celebratory. I think Bascom’s reimagining or demonstrating of the square dance is kind of a queer thing — and by “queer,” in this moment, I mean a set of stylistics that are somehow “beyond,” somehow an outsider, that have that “crooked” or critical relationship to the normative. Making that first piece a solo square dance and building the rest of the show around it, I tried to think so much about the way that dance possibly enacts some kind of revolutionary potential. Through touch, through interaction of sound and gesture, through [considering] what it might be like to have communities that move together, and what it might be like to have an individual that a community watches.

In all those things, I kept coming up against this idea that there are, indeed, heteronormative facets of that. Like [in square dancing] when we say, “Gents, swing your corner lady.” We say only “gents” and “ladies.” We say only, “Gents do this.” So there’s also a patriarchal power there, in who does what to whom. There’s also a binary that doesn’t allow for, perhaps, the existence of something like polyamory, where there are multiple people involved in a romantic or physical connection. I started thinking about what it would be like, if instead of singing, [Sings] “I’m gonna get that, get that, get that, I’m gonna get that pretty little girl,” what is it like if someone who performs the gender that I perform sings about someone who has a similar gender as themself? That subtle switch turns more than I ever could’ve imagined. It didn’t take putting on heels and a feather boa to queer square dance, just the simple expression of speaking about intimacy, thinking about the gender dynamics of that special social form, and then creating that little shift in the reiteration of that call. Which, I’m really happy about! At first, to decide, I’m gonna “queer” traditional dance — it’s a little bit of an arduous project. I’m finding that it’s these subtle nuance shifts that maybe make the biggest strides to imagining anti-normative futures as well as pasts.

I read an interview of yours, years ago now, in which you mentioned so succinctly that straight people have always let their identities shine through their art, so why wouldn’t queer people do that, too? That was a groundbreaking moment for me, realizing that my identity has an equal right to being included in my art, because no one else is filtering out their identities, their identities just happen to be the norm. It doesn’t take a lot of effort, like you were just saying, it just takes a change in perspective to open that paradigm up. How do we help all kinds of folks to realize that anti-normative future that you see?

I think it’s important to remember that queer people are not a facet of postmodernity. Queerness has always existed.

That’s such an important point! It just hasn’t always been visible.

Right. When we think about traditional music, oftentimes we relate that not only to a particular place, but a particular time. It’s important to remember that there have always been LGBTQIA+ people in those historical moments, again, whether those people were allowed to visible or whether it was okay for them to be visible is another question. Now, some of what we’re starting to see is nascent queerness beginning to whisper, or to sing, or to dance. That feels like a very exciting time, but we’re not inventing that. Queerness [has] been around for a long time.

For example, people who sing ballads, who maybe keep the pronoun of the song the same, or maybe switch pronouns to express a sexual object choice that is somehow other than straight, this is a simple, subtle way people have always enacted some kind of queer performance. And for a long time! I don’t only think that it’s always related to romantic connections, to be honest. I really like the idea of queerness as a critical set of stylistics. For instance, my relationship to percussive dance is a little queer — or bent — because I had a teacher who always said, “There will be no scraping in our class.” That means, in percussive dance, good technique is a sharp, short, adroit connection to the floor, where you strike your foot against the ground, but you don’t leave it on the ground. That, for me, sort of became a provocation. It made me want to slide my foot, to whisper, to create this foot-to-floor fricative, for many reasons: One, it got me closer to a fiddle’s bow, sliding slowly across the strings, but secondly, simply for the pure joy of transgressing! It opens this world of other tambours I didn’t have access to before.

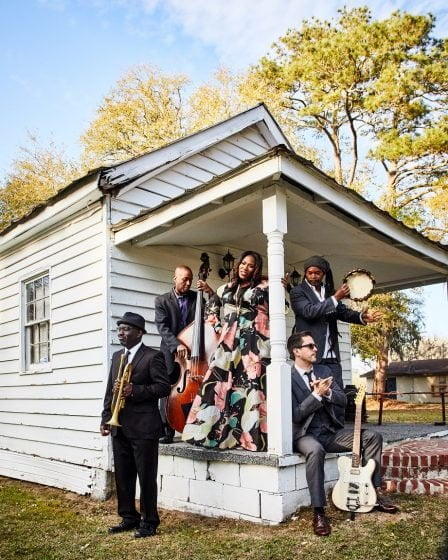

So then, in conclusion, if a reader and roots music fan is looking to have their ideas about traditional and percussive dance queered, where will they be able to find you in the near future?Solo Square Dance will continue to tour, there are shows in Ireland and Scotland lined up. I have a new project called DuoDuo with cellist Natalie Haas, guitarist Yann Falquet, harpist Maeve Gilchrist, and myself. That project is out on the road. Also, my band, This Is How We Fly, is getting together to make our third record starting in November, which is very exciting. Then, in the fall, I’m touring with this incredible tap dancer, who is also interested in vernacular dance forms, vernacular jazz and swing — his name is Caleb Teicher. We have a duo dance project, again a project without any instruments! Just us, making the music with our bodies and voices.

Because dance is music, damnit.

Exactly! And, to be honest, music is dancing as well! [Laughs] I found, in my collaborations with musicians, when there’s a moving body on stage, musicians begin to consider their own bodies a little bit more. They start to think about where they stand and how they move. It’s actually an interesting metamorphosis to witness and be engaged with. It reminds everyone that if one person can cross the sound/movement divide, if a dancer can be heard, maybe a musician can be seen!

Editor’s Note: Gareiss will be featured in the Bluegrass Situation Presents: A St. Patrick’s Day Festival at New York’s New Irish Arts Center, participating in an opening night jam session with fiddler-banjoist Jake Blount, clawhammer banjoist Allison de Groot and fiddler Tatiana Hargreaves on March 17 as well as a headlining performance with Blount on March 18.

Photo credit: Darragh Kane